What Explains Trumpism?

It’s capitalism, and it’s global.

There are many problems with the American political system: the Electoral College, an undemocratic Senate, and a right-wing Supreme Court among them. Then there’s America’s deep racism, combined with sexism and xenophobia. But Trumpism goes beyond Trump—and extends beyond the borders (walled or not) of the United States.

The phenomenon of right-wing populism is wide-ranging, appearing in far-right parties in Western Europe, in Orbán’s Hungary, in Putin’s Russia, Erdoğan’s Turkey, Bolsonaro’s Brazil, and Modi’s India. While country-level traits can help us understand individual cases, when the same phenomenon repeats itself, a higher level of analysis is needed. The one thing these varied countries share is that they are all deeply embedded in the global capitalist economy.

With the ascent of capitalist globalization—beginning in the Reagan/Thatcher era, or even with Jimmy Carter’s deregulation—national governments became less and less capable of shaping outcomes that could positively impact the lives of their citizens. Capital became global, seeking lower taxes, less regulation, and cheaper wages. Financial markets followed the whims of fluctuating interest rates and currencies across the world.

In short, the economy became global, but politics did not. The vessel of national politics could no longer contain the forces that were central to people’s daily lives, such as well-paying jobs and a decent standard of living.

Elections would take place, governments come and go, but for many people there was little sense of meaningful change. As a result, trust in public institutions has dropped precipitously worldwide. Yet the anguish was not shared equally. Capital flowed into global cities, drawing in educated professionals, with other places “left behind” to deal with “deaths of despair.” The parties of the center-left followed the new centers of gravity toward urban professionals. But in the game of electoral politics, they failed to protect their flank.

Little wonder, then, about the appeal of nationalism, the desire to “take back control” and “make our country great again.” Meloni and Le Pen aside, these would-be autocrats are all male. Their appeal can partly be explained by the relative decline of (especially less-educated) men in increasingly postindustrial societies. But the strongman also projects a sense of muscular protection against forces that appear to be out of control.

By its nature global capitalism is a mysterious phenomenon, one without an address or a figurehead. Conspiracies provide a coherent narrative, a sense of understanding and comprehension over otherwise amorphous forces shaping one’s life. Most often they address a vexing question: Who is to blame?

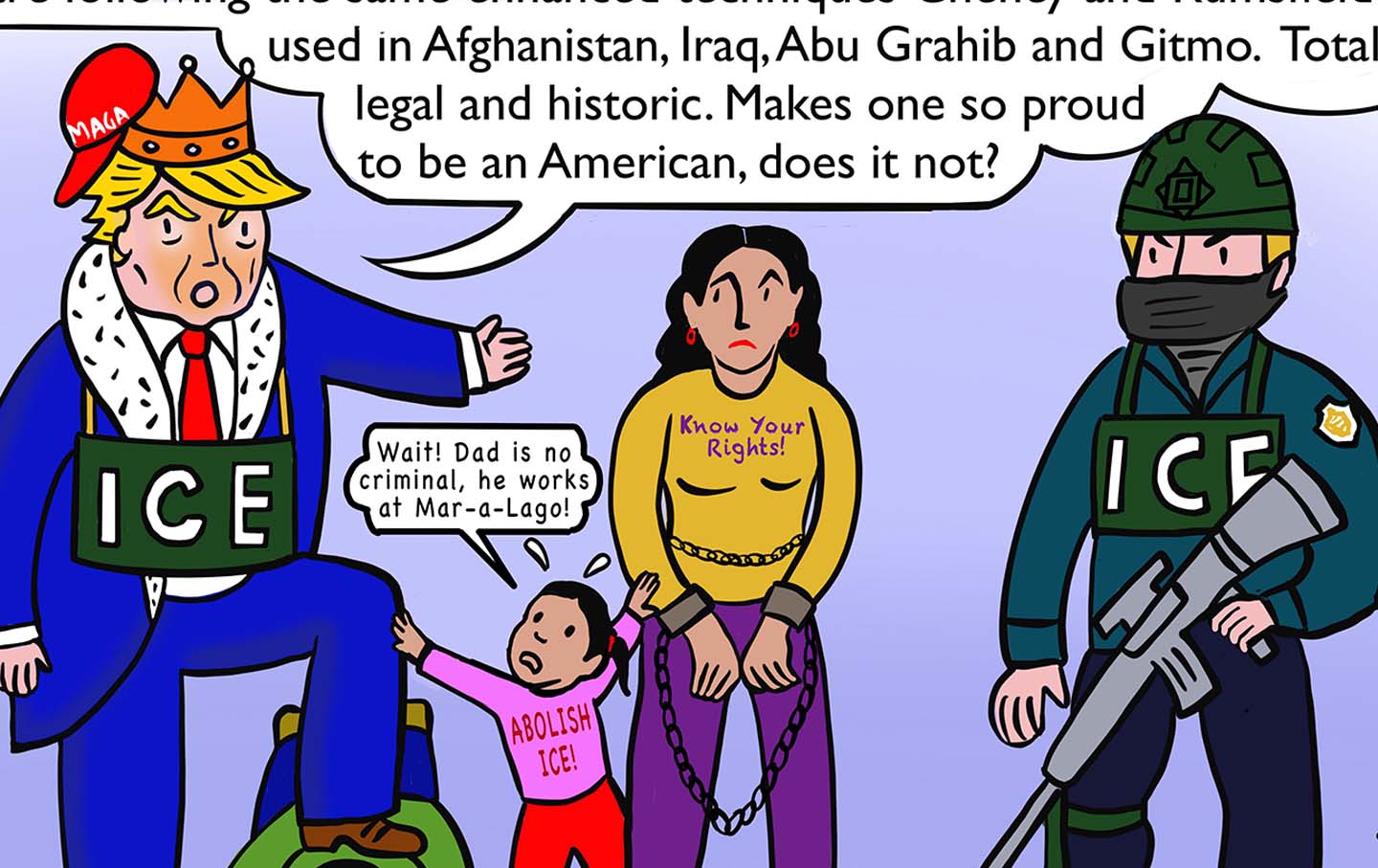

The strongmen provide a ready answer. Yet whether they are self-proclaimed billionaires like Trump or rely on the backing of oligarchs, their storyline must solve the conservative dilemma: How, in societies with even just a veneer of democracy, do conservatives convince people to support policies that benefit the über-wealthy? The strongman’s tactic is simple: punch down. Place the blame on immigrants, on ethnic, religious, or sexual minorities. You might blame an amorphous “elite,” but never the capitalist class.

While Elon Musk was literally dancing for Trump, and Jeff Bezos apparently pulled the endorsement of his Washington Post to avoid alienating the presumed future president, one study found that 150 billionaire families contributed close to $2 billion to sway elections this year. They’ve already received a dramatic return on their investment: the wealth of the world’s 10 richest people—a list dominated by US tech billionaires—increased by $64 billion on the single day after Trump’s election.

Still, although 72 percent of all billionaire funding flowed to Republicans, a larger number of billionaires backed Harris over Trump. What better illustration is there of the oligarchic capture of our politics? For whom do you vote if you believe that billionaires themselves are the problem?

There is little prospect that capitalism, especially in its global form, will come to an end anytime soon. But without guardrails, capitalism will continue to run amok, trampling our politics and poisoning our planet. For that to change, the oligarchs of the world need to realize that capitalism without limits will devour themselves along with the rest of us.

In his study of oligarchic rule in a variety of societies across history, Jeffrey Winters found that the one element they shared was the overriding desire to defend their wealth. Today’s oligarchs must be reminded that they stand on the top of human pyramids, propped up by masses of people, people who bear immense weight on their backs and shoulders.

In short, the oligarchs of the world need to fear that if enough people rise up and shake that pyramid, the fall down would be long and hard. Their vast wealth could vanish, and there is nowhere—not New Zealand, not Mars—to run and hide. The oligarchs need to be shaken, to be brought to their senses, before it is too late for all of us.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →Disobey authoritarians, support The Nation

Over the past year you’ve read Nation writers like Elie Mystal, Kaveh Akbar, John Nichols, Joan Walsh, Bryce Covert, Dave Zirin, Jeet Heer, Michael T. Klare, Katha Pollitt, Amy Littlefield, Gregg Gonsalves, and Sasha Abramsky take on the Trump family’s corruption, set the record straight about Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s catastrophic Make America Healthy Again movement, survey the fallout and human cost of the DOGE wrecking ball, anticipate the Supreme Court’s dangerous antidemocratic rulings, and amplify successful tactics of resistance on the streets and in Congress.

We publish these stories because when members of our communities are being abducted, household debt is climbing, and AI data centers are causing water and electricity shortages, we have a duty as journalists to do all we can to inform the public.

In 2026, our aim is to do more than ever before—but we need your support to make that happen.

Through December 31, a generous donor will match all donations up to $75,000. That means that your contribution will be doubled, dollar for dollar. If we hit the full match, we’ll be starting 2026 with $150,000 to invest in the stories that impact real people’s lives—the kinds of stories that billionaire-owned, corporate-backed outlets aren’t covering.

With your support, our team will publish major stories that the president and his allies won’t want you to read. We’ll cover the emerging military-tech industrial complex and matters of war, peace, and surveillance, as well as the affordability crisis, hunger, housing, healthcare, the environment, attacks on reproductive rights, and much more. At the same time, we’ll imagine alternatives to Trumpian rule and uplift efforts to create a better world, here and now.

While your gift has twice the impact, I’m asking you to support The Nation with a donation today. You’ll empower the journalists, editors, and fact-checkers best equipped to hold this authoritarian administration to account.

I hope you won’t miss this moment—donate to The Nation today.

Onward,

Katrina vanden Heuvel

Editor and publisher, The Nation