The True Source of Trump’s Delusions: The Gospel of Positive Thinking

Trump’s obsession with crowd sizes is part of his lifelong quest to prevent reality from blocking his path to success.

A section of empty seats at an event headlined by former president Donald Trump in Commerce, Georgia, on March 26, 2022.

(Elijah Nouvelage / Bloomberg via Getty Images)

Donald Trump’s obsession with the size of the crowds turning out for the Harris-Walz ticket speaks volumes about the waning momentum behind his third presidential run—but not in the way that many commentators have suggested. This weekend’s Truth Social outburst claiming that the crowd that greeted Kamala Harris and Tim Walz at the Detroit airport was conjured by artificial intelligence represents an early effort to discredit the presidential balloting in advance, writes Washington Post analyst Philip Bump—a prelude to another January 6 insurrection should Trump once again lose. Trump detractors on social media, meanwhile, have suggested that the candidate’s evidence-free attack on the reality of Democratic rallies represents his ongoing slide into dementia and delusion, with some likening the candidate to Captain Queeg, the unhinged Naval officer played by Humphrey Bogart in The Caine Mutiny.

It’s true that Trump is exhibiting even greater signs of mental decline than usual—just as it’s true that the Trump campaign’s plans to delegitimize and overturn an adverse election result are distressingly advanced in comparison to the January 6 putsch. Yet neither the candidate’s losing battle with dotage nor the prospect of another post-election coup attempt accounts for the depth of Trump’s fixation with crowd numbers. The brand of delusion Trump is now indulging has been integral to his character from the outset of his tabloid-fueled rise to public prominence. Far from representing a new detour into paranoid fantasies, it marks the most coherent belief system that the 45th president endorses: the gospel of positive thinking.

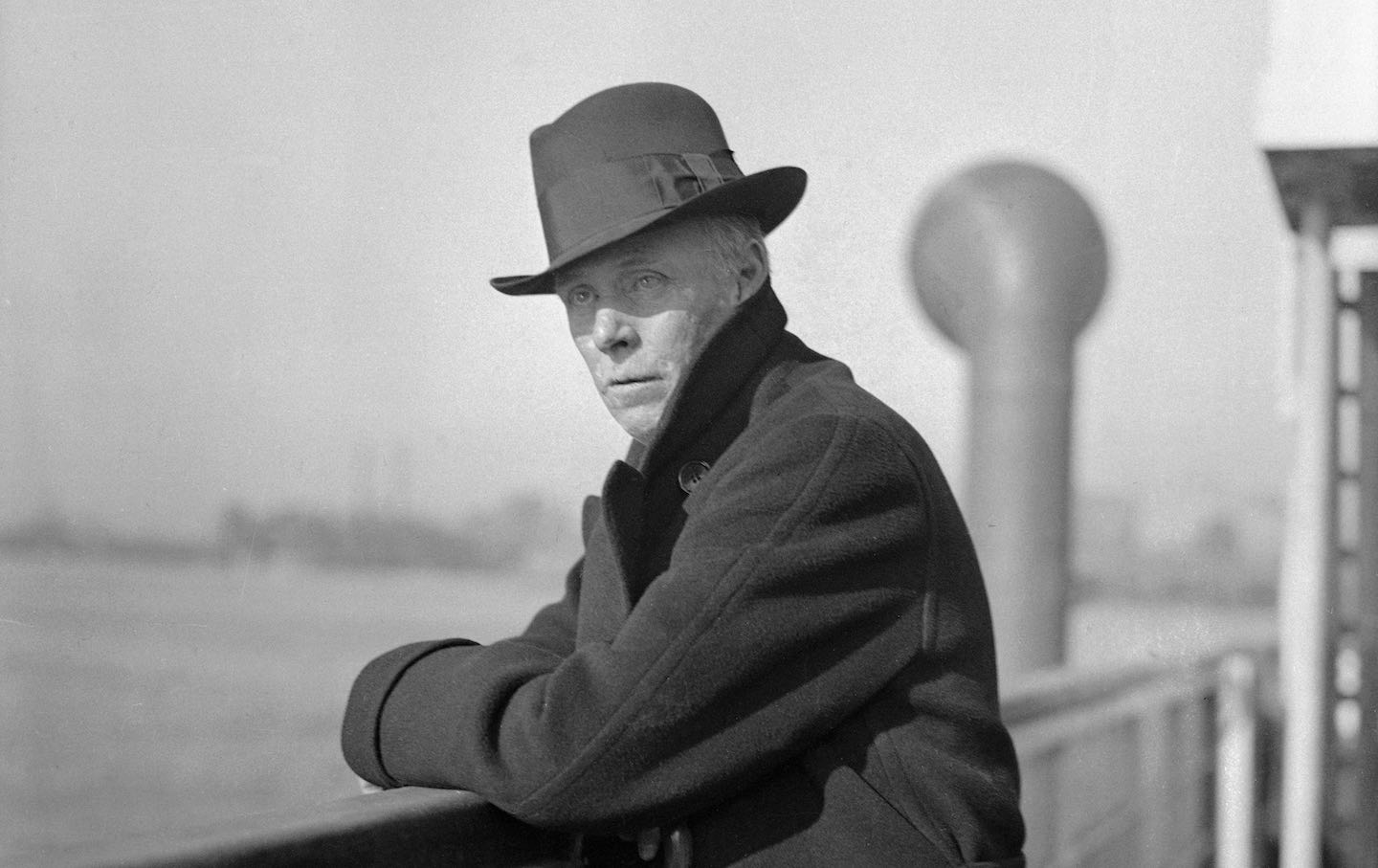

For all his prophesying about national decline, Trump is an apostle of Norman Vincent Peale’s theology of modern self-improvement, as laid out in the Protestant cleric’s best-selling 1952 tract, The Power of Positive Thinking. As a child, Trump regularly attended Peale’s weekly sermons at the Marble Collegiate congregation in Manhattan. Peale officiated over Trump’s first wedding in 1977, and Trump has cited the foundational influence of Peale’s teachings throughout his life.

How do the basic doctrines of Pealeism translate into something as nutty as Trump’s belief that the huge crowds turning out for his Democratic rivals are a tech-manipulated mirage? The basic idea is simple: Peale preached that the key to success was to intone a steady string of motivational mantras—usually, wrenched out of all recognizable context, from the Bible—as a way to guarantee self-advancement. In the jargon of today’s self-help industry, Peale taught believers that to manifest their material well-being was the surest path to an abundant and untroubled life ordained by God. “Picturize, prayerize, and actualize” was Peale’s mantra to the upward-striving faithful.

Trump is a nihilist in most other respects, but he cleaves to the precepts of positive thinking amid the upheavals of his personal and public life. When he sued New York Times reporter Tim O’Brien in 2006, disputing O’Brien’s claim that Trump’s net worth didn’t justify Trump’s self-designation as a billionaire, Trump explained in a deposition that he was indeed a billionaire because he felt like one on most days. “I like to be as positive as I can with respect to my properties,” he said, before going into a fanciful account of how a 30 percent interest on one such holding translated into a 50 percent one, because “I have always felt that I own 50 percent.”

In his political life, the scale of rally crowds likewise occupies an outsize place in Trump’s imagination. At the outset of his administration, Trump dispatched his then–press secretary Sean Spicer to announce before the White House press corps that Trump’s Inauguration Day crowd was nothing less than “the largest audience to ever witness an inauguration, period, both in person and around the globe.”

In later self-aggrandizing flourishes, Trump would claim to have drawn a devoted following that well outnumbered the fans thronging to see Elton John. In reality, that rally crowd was 6,500—a turnout that would likely prompt a cancellation on an Elton John tour. But the facts on the ground weren’t remotely relevant to the president’s perfervid picturizing: “So we break all of these records,” Trump enthused. Really we do it without, like, the musical instruments. This is the only musical [sic]: the mouth. And hopefully the brain attached to the mouth.”

Nor, it should be noted, is Trump’s fixation on crowd sizes without relevance to explaining his broader appeal. It was the mainstream media’s similarly vacuous obsession with scale and spectacle that prompted cable networks like CNN to brainlessly consign acres of airtime to unfiltered coverage of Trump rallies during the 2016 cycle. That derogation of journalistic duty translated into some $5 billion worth of free media for Trump by Election Day 2016. In seeing his anemic recent rallies bested by Harris and Walz, Trump correctly senses that his 2016 shtick is starting to wear thin—and since it is also an article of positive thinking that one can bend the prevailing terms of reality to your own success mantras, Trump is mostly frozen in horrified incomprehension before the new evidence. It’s therefore essential that the evidence be dismissed and delegitimized; the only logical alternative in Pealeism is the inadmissible thought that the positive thinker is on a self-charted rendezvous with failure.

This, not incidentally, is the same logic that impelled Trump to launch the false crusade to discredit the result of the 2020 election: It wasn’t that he discerned a vast Democratic plot; it was that a Trump loss was simply unthinkable, and therefore could not exist. (See also Trump’s bid to discredit his only 2016 primary defeat in Iowa, to Ted Cruz, on exactly the same bogus grounds.)

This is why, as the images of the Harris-Walz rally in Detroit coursed through the mediasphere last week, Trump convened a confused press conference at his Mar-a-Lago compound. The dipshit political desk at The New York Times treated that performance as a standard campaign maneuver to “wrestle attention back” from the Democratic ticket, when it was really the telltale glitching of positive-thinking dogma in the face of brutal and incontrovertible evidence to the contrary.

During that press conference, Trump went out of his way then to claim that the crowd he’d drawn for the infamous “Stop the Steal” rally on January 6, 2021, was larger than the audience for Martin Luther King’s “I Have a Dream” speech on the National Mall, while also falsely insisting that “nobody was killed” during the Capitol insurrection. These are dangerous and authoritarian delusions, but they don’t stem from the GOP’s 2024 election subversion playbook or Trump’s descent into madness. The only thing that differentiates this round of Trump’s megalomaniacal obsessions is that he can no longer count on the likes of Sean Spicer and Jeff Zucker to emblazon them across the nation.

Disobey authoritarians, support The Nation

Over the past year you’ve read Nation writers like Elie Mystal, Kaveh Akbar, John Nichols, Joan Walsh, Bryce Covert, Dave Zirin, Jeet Heer, Michael T. Klare, Katha Pollitt, Amy Littlefield, Gregg Gonsalves, and Sasha Abramsky take on the Trump family’s corruption, set the record straight about Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s catastrophic Make America Healthy Again movement, survey the fallout and human cost of the DOGE wrecking ball, anticipate the Supreme Court’s dangerous antidemocratic rulings, and amplify successful tactics of resistance on the streets and in Congress.

We publish these stories because when members of our communities are being abducted, household debt is climbing, and AI data centers are causing water and electricity shortages, we have a duty as journalists to do all we can to inform the public.

In 2026, our aim is to do more than ever before—but we need your support to make that happen.

Through December 31, a generous donor will match all donations up to $75,000. That means that your contribution will be doubled, dollar for dollar. If we hit the full match, we’ll be starting 2026 with $150,000 to invest in the stories that impact real people’s lives—the kinds of stories that billionaire-owned, corporate-backed outlets aren’t covering.

With your support, our team will publish major stories that the president and his allies won’t want you to read. We’ll cover the emerging military-tech industrial complex and matters of war, peace, and surveillance, as well as the affordability crisis, hunger, housing, healthcare, the environment, attacks on reproductive rights, and much more. At the same time, we’ll imagine alternatives to Trumpian rule and uplift efforts to create a better world, here and now.

While your gift has twice the impact, I’m asking you to support The Nation with a donation today. You’ll empower the journalists, editors, and fact-checkers best equipped to hold this authoritarian administration to account.

I hope you won’t miss this moment—donate to The Nation today.

Onward,

Katrina vanden Heuvel

Editor and publisher, The Nation