The UAW Is Prepared to Strike, and Bernie Sanders Has Their Back

In a fight over the future of work, the labor committee chair recognizes that autoworkers need a fair share of burgeoning profits.

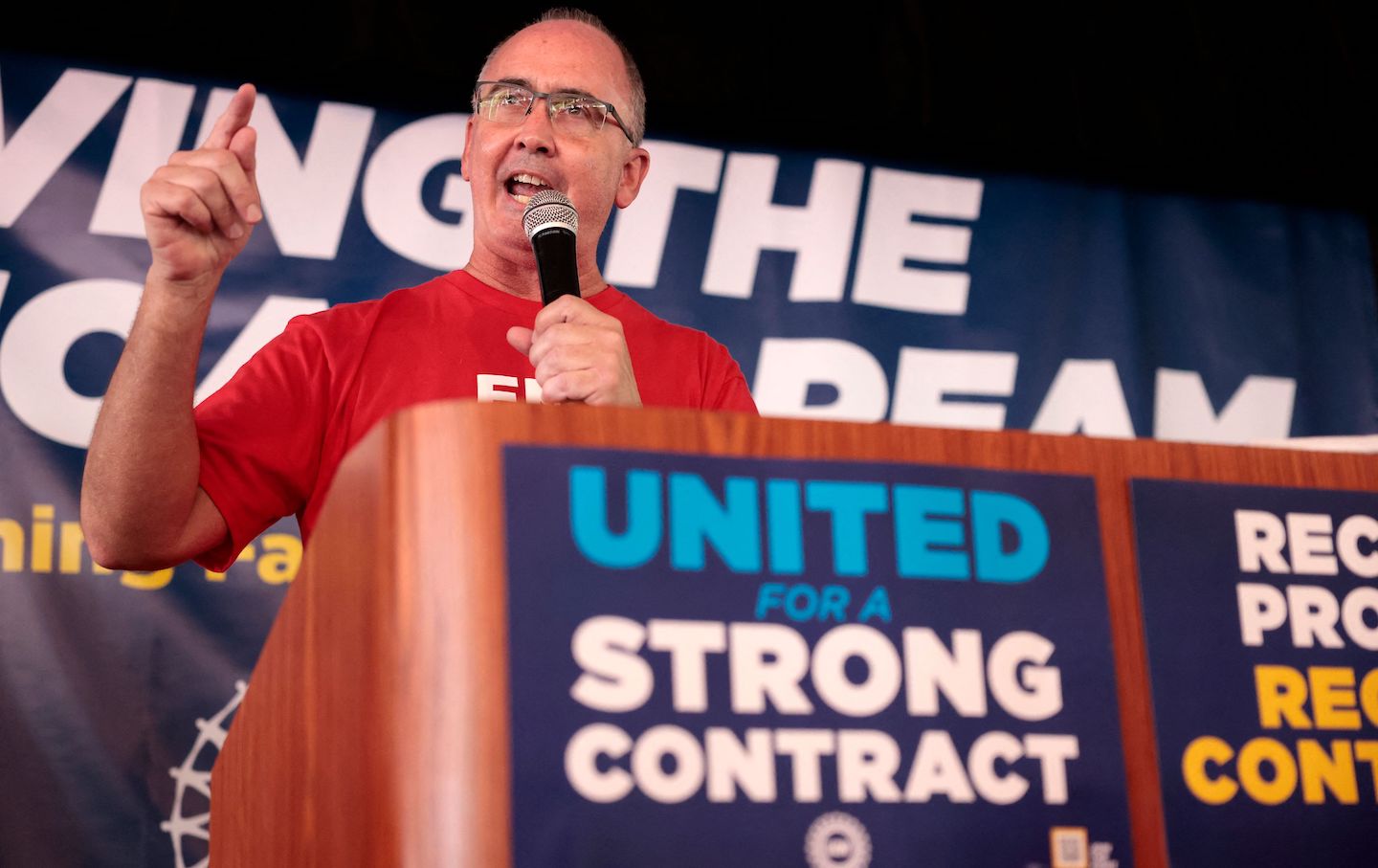

United Automobile Workers President Shawn Fain speaks as UAW members and their supporters gather for Solidarity Sunday in Warren, Mich., on August 20, 2023.

(Photo by Jeff Kowalsky / AFP via Getty Images)The United Auto Workers union recognizes that this is a determining moment for the future of work in America. Either UAW members who are employed by the “Big Three” auto companies get a fair contract that respects the rights of workers in a rapidly automating and transforming industry, or Wall Street will define the future of American manufacturing as a bottom-project that disregards workers and their communities.

That’s why the UAW refers to current negotiations with General Motors, Ford, and Stellantis (the global vehicle-making conglomerate that owns Chrysler) as “our generation’s defining moment at the Big 3.”

The UAW’s 150,000 members know what’s at stake. Ninety-seven percent of them have voted to authorize a strike if a new contract is not secured by the time that the union’s old contract with the auto companies expires on September 14. And not just any new contract. The union wants a 46 percent pay hike and improved health care and retirement benefits, which members see as the reasonable due for workers in an industry that made $250 billion in North American profits over the past decade. “Our union’s membership is clearly fed up with living paycheck to paycheck while the corporate elite and billionaire class continue to make out like bandits,” says newly elected UAW President Shawn Fain, noting that the automakers made a combined $21 billion in profits in the first six months of 2023 alone. “That’s on top of the quarter-trillion dollars in North American profits they made over the last decade. While Big Three executives and shareholders got rich, UAW members got left behind. Our message to the Big Three is simple: record profits mean record contracts.”

But the UAW, a historically visionary union, also wants a say in defining the future of an industry that has traditionally set the standard for the treatment of workers in American manufacturing. So it is that, at a time when automation and the rapid rise to electric-vehicle manufacturing is remaking the auto industry, the UAW is demanding a 32-hour workweek without losing pay, a right to strike to prevent plant closures, and equal pay for equal work, with an end to tiered pay scales and the mistreatment of temporary workers. While Fain admits that “these demands sound ambitious,” he correctly argues that this is a fight over the future of work, and it has ramifications that extend far beyond the nation’s auto plants.

That’s one of the reasons US Senator Bernie Sanders, the chair of the powerful Senate Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions Committee, has been so urgent in his support of the UAW and its contract demands. While it is relatively rare for key figures in Congress—especially the chair of what was once known as the Senate Labor Committee—to explicitly support a strike threat, Sanders says, “I very strongly support the UAW and their new leadership. I certainly hope there is not going to be a strike. No one wants a strike. But the Big Three have got to understand they cannot have it all.”

There is no question that the stakes are high, and not just for the Big Three; the future of work is an issue that extends beyond the auto industry. In our recent book, It’s O.K. to Be Angry About Capitalism, Sanders and I examine the ways in which the US economy is changing with the introduction of AI technology, automation, new modes of transportation, and new approaches to the workday and the workplace. Recognizing that technological change will lead to increased productivity and profits, we ask whether the benefits of these shifts will be enjoyed by workers and the communities where factories are located. The answer, of course, is that this will only happen if unions demand a fair share for the people who made the United States an industrial powerhouse. It’s not right, argues Fain, that industry CEOs enjoy record pay while UAW members “have to work longer and harder just to maintain the same standard of living that we had before.”

A contract win, with the pay and protections that the UAW proposes, has the potential to change that equation, and to renew the economic vitality of an industry that has seen 65 plants close over the past two decades. That’s especially important as plants are being retooled to produce electric vehicles—which require a dramatically different, and in some ways more easily automated, manufacturing processes—and to produce the batteries that power them. This reality makes the negotiations between the Big Three and the union a defining moment for the transition toward a green economy that must be good for workers and for the environment.

Whenever fights of this sort play out, they become, as the great union songwriter Florence Reece taught us, “Which Side Are You On?” moments.

Sanders has taken his side, clearly and unequivocally. “These workers are getting squeezed while the guys at the top have never had it so good,” he explains. “And what these workers are saying is, No, it is unacceptable that while the Big Three auto companies are making record-breaking profits, the autoworkers who are responsible for those profits are not receiving decent wages and benefits.”

The senator is not alone. A growing chorus of prominent Democrats and members of Congress are singing “Solidarity Forever” with UAW members, even as President Joe Biden maintains the traditional union-friendly but cautious tone of Democratic presidents when faced with the prospect of a major strike. In an August 14 statement, the president declared that “the transition to a clean energy economy should provide a win‑win opportunity for auto companies and unionized workers.”

Former labor secretary Robert Reich has been far blunter than the president. Reich scoffed last week at industry claims that the UAW’s wage demands are audacious. “The UAW is demanding a 40 percent wage increase for workers. Why? That’s exactly how much pay has spiked for the CEOs of Ford, GM, and Stellantis,” he noted. “When workers demand fair pay, there’s an uproar. But nobody bats an eye when exec pay skyrockets. Funny how that works, huh?”

Earlier this summer, US Senator Sherrod Brown (D-Ohio) led 28 senators in urging the CEOs of the major auto companies “to negotiate in good faith to reach a fair outcome by agreeing to fold workers at all joint venture electric vehicle battery facilities into the national UAW contract.” At a huge mid-August rally of UAW members in Michigan, a trio of Democrats from that state—US Representatives Debbie Dingell, Rashida Tlaib, and Haley Stevens—embraced the UAW’s contract agenda. In what she describes as a fight over “the jobs of the future,” Dingell has for months been expressing solidarity with UAW members. At the same time, US Representative Ro Khanna, a tech-savvy California Democrat who has been on the cutting edge of future-of-work issues, has been traveling extensively in the historic union towns of the Great Lakes states this summer, arguing that “if you’re going to have the new energy, the clean energy jobs, the battery plants, they’ve got to pay the same as the auto plants paid.”

As contract negotiations heat up, Khanna says, “I stand in complete solidarity with the UAW. The blame here is with the Big Three automakers’ refusal to grant their workers a fair contract. The Big Three are getting billions of taxpayer dollars. They owe the workers fairness.”

Disobey authoritarians, support The Nation

Over the past year you’ve read Nation writers like Elie Mystal, Kaveh Akbar, John Nichols, Joan Walsh, Bryce Covert, Dave Zirin, Jeet Heer, Michael T. Klare, Katha Pollitt, Amy Littlefield, Gregg Gonsalves, and Sasha Abramsky take on the Trump family’s corruption, set the record straight about Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s catastrophic Make America Healthy Again movement, survey the fallout and human cost of the DOGE wrecking ball, anticipate the Supreme Court’s dangerous antidemocratic rulings, and amplify successful tactics of resistance on the streets and in Congress.

We publish these stories because when members of our communities are being abducted, household debt is climbing, and AI data centers are causing water and electricity shortages, we have a duty as journalists to do all we can to inform the public.

In 2026, our aim is to do more than ever before—but we need your support to make that happen.

Through December 31, a generous donor will match all donations up to $75,000. That means that your contribution will be doubled, dollar for dollar. If we hit the full match, we’ll be starting 2026 with $150,000 to invest in the stories that impact real people’s lives—the kinds of stories that billionaire-owned, corporate-backed outlets aren’t covering.

With your support, our team will publish major stories that the president and his allies won’t want you to read. We’ll cover the emerging military-tech industrial complex and matters of war, peace, and surveillance, as well as the affordability crisis, hunger, housing, healthcare, the environment, attacks on reproductive rights, and much more. At the same time, we’ll imagine alternatives to Trumpian rule and uplift efforts to create a better world, here and now.

While your gift has twice the impact, I’m asking you to support The Nation with a donation today. You’ll empower the journalists, editors, and fact-checkers best equipped to hold this authoritarian administration to account.

I hope you won’t miss this moment—donate to The Nation today.

Onward,

Katrina vanden Heuvel

Editor and publisher, The Nation