By promising to clamp down on corruption, City Controller Kenneth Mejia received more votes than any citywide elected official in Los Angeles history. He’s already making enemies.

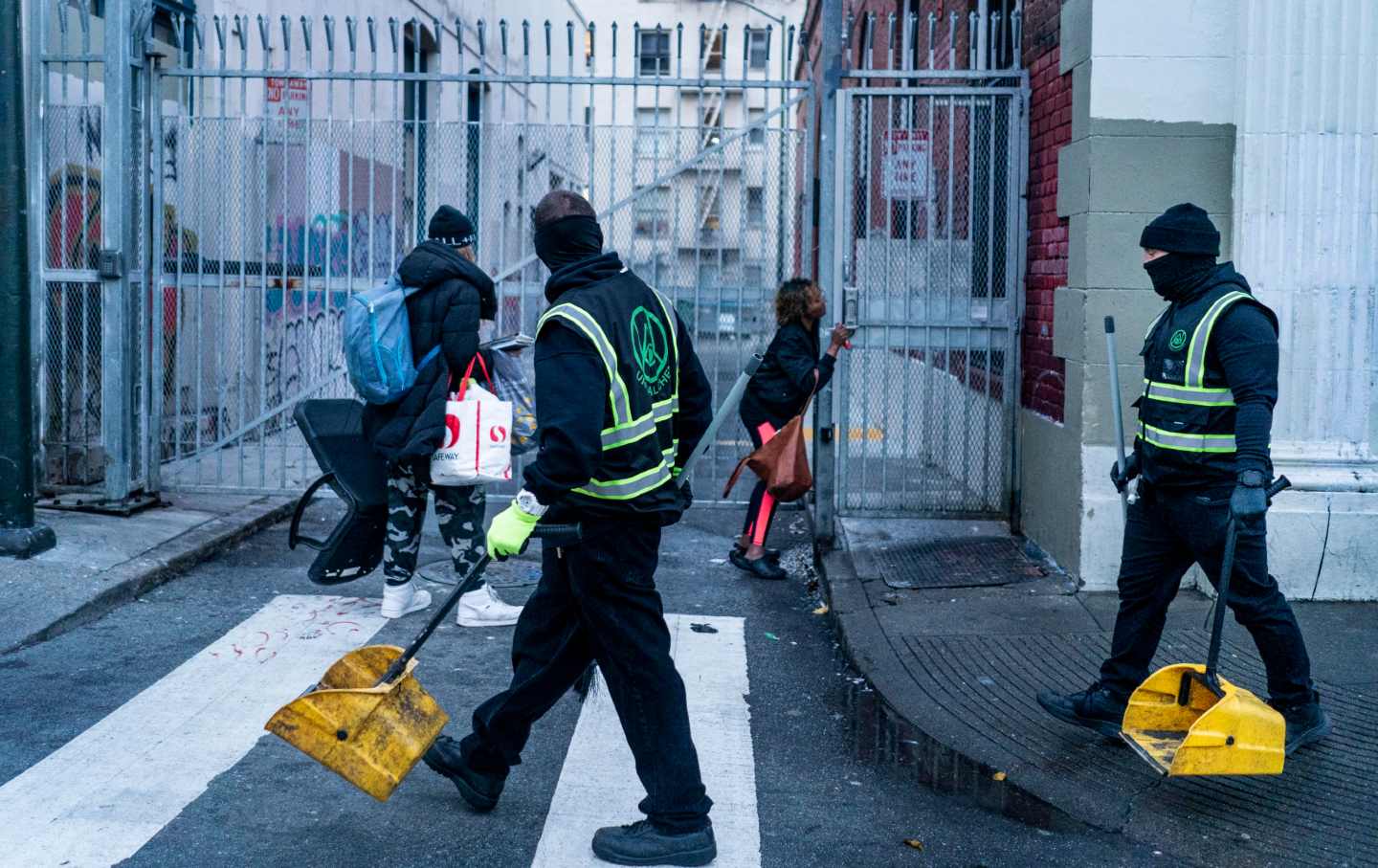

A homeless man and woman quickly pick up their belongings as Urban Alchemy crews begin their daily cleaning of the streets in the Tenderloin neighborhood of San Francisco on January 26, 2022.(Melina Mara / The Washington Post via Getty Images)

On a January night at Skid Row in Los Angeles, an employee from Urban Alchemy was filmed hosing down a sidewalk just feet from a homeless resident. Under the streetlights, the homeless person is on their knees wrapped in a blanket and appears to be scrambling to pick up their belongings before they’re soaked.

The city of Los Angeles, like a handful of other metro areas, pays the San Francisco–based nonprofit millions of dollars to patrol the streets and provide outreach to homeless individuals.

The video sparked outrage. LA City Controller Kenneth Mejia announced an investigation into the nonprofit, and within days, Urban Alchemy claimed to have fired the worker, calling his actions “unacceptable.”

At first the city controller’s investigation went smoothly. The nonprofit complied with the office’s initial request for financial information, according to Sergio Perez, the chief of accountability and oversight for the controller’s office.

But after being asked to provide additional contractual information, the nonprofit stopped cooperating. Then in June, Urban Alchemy took to X to denounce the controller’s investigation as “cynical and politically motivated” and an “abuse of [Mejia’s] power.”

Subsequently, Urban Alchemy sued the controller’s office to halt a subpoena issued to reveal that information. The LA city attorney and city council appear to have blocked the controller’s office from fighting the lawsuit.

The city attorney’s office said it “did its job” and that the controller should not have gone digging further into Urban Alchemy. Regarding the incident, Urban Alchemy blames “activists, including the controller’s team,” and the media for overblowing “what could have been a teaching moment for an employee who made a mistake.” Instead, Urban Alchemy said it cost them and “the City of Los Angeles time and money.”

After months, the end result may be a less transparent city government.

The incident on Skid Row isn’t the first time an Urban Alchemy employee has been accused of wrongdoing and then not fired. In the last six months, two former employees of Urban Alchemy filed lawsuits against the nonprofit, each alleging that a supervisor in San Francisco sexually harassed female staffers. In both cases, the same supervisor gave extended nonconsensual hugs and harassed the women. In one case, he begged his employee to go out with him, asked if her lesbian marriage was a “prison thing,” and tried to get the employee to join him in his office cot.

The other case is even more disturbing: In September, the supervisor fondled a staffer’s genitals, while saying “it’s so warm, can I smell it and taste it?” Months later he did not ask permission before he pulled his pants down, ejaculated on the woman, and put his finger inside her. The case will go to a jury trial in 2025.

In both cases, the supervisor dangled job promotions and opportunities in exchange for sexual attention: “Don’t you want to make more money? I can help you out with housing,” he said.

A few weeks after the first lawsuit was filed, Urban Alchemy transferred the manager to Portland, Oregon, where he was given another supervisory role. “The claims made in this lawsuit are baseless and cynical, and we are confident there is no truth to them,” Urban Alchemy’s chief of government and community affairs, Kirkpatrick Tyler, said back in March to The San Francisco Standard. (Tyler served as a senior policy adviser on homelessness for former LA Mayor Eric Garcetti.)

Based in San Francisco, Urban Alchemy has grown rapidly since its founding in 2018, winning contracts worth tens of millions of dollars across California and in Portland and Austin, Texas. By 2026, it hopes to have $100 million in contract revenue.

According to its website, the group uses that money to transform the “energy in traumatized urban spaces.” The organization does this by hiring mostly formerly incarcerated individuals as “ambassadors” to clean and patrol homeless encampments and public streets. Ambassadors are not licensed security guards, though many of them list themselves as such on LinkedIn. They stand sentry on street corners wearing reflective, municipal-looking uniforms, emblazoned with the group’s all-seeing-eye logo. “Once you see us,” one Urban Alchemy slogan reads, “you can’t unsee us.”

At the beginning of this year, Urban Alchemy’s proponents, who include San Francisco Mayor London Breed, trumpeted a study that appears to show that the presence of the group’s ambassadors at 40 intersections in the Tenderloin, SoMa, and Midmarket significantly reduced crime. The city is paying Urban Alchemy upwards of $8 million to flood this part of San Francisco with dozens of ambassadors from 7 am to 7 pm. The study compared rates of crimes committed during the ambassadors’ working hours 12 months before and after the ambassadors were added—a period of time in which crime dropped in cities across the country.

Urban Alchemy’s founder and CEO, Lena Miller, told the San Francisco Examiner in January that “this data” was “proof” of the group’s effectiveness.

The study, however, was not peer-reviewed, published, or even finished, as the Examiner pointed out.

A number of Urban Alchemy ambassadors have also been accused—and convicted—of serious crimes themselves, including attempted murder. Over the years, the nonprofit has faced at least eight lawsuits in San Francisco county alone, and as of this year also faces a RICO lawsuit in the Bay Area and lobbying violations in Portland.

Dozens of people experiencing homelessness have said in lawsuits and told us and reporters at other outlets that Urban Alchemy ambassadors have harassed, threatened, or assaulted them.

In 2021 at the start of the Covid-19 pandemic, Urban Alchemy began operating in Los Angeles, initially providing sanitation stations for unhoused residents and then expanding to operating city-sanctioned tent encampments. It has gone on to receive at least $14 million from the city, including $2.6 million to lead a pilot program called CIRCLE—”Crisis and Incident Response through Community-Led Engagement”—that is supposed to provide an alternative to calling 911.

That same year, the city, under then-Mayor Garcetti reestablished its 41.18 ordinance, which prohibits “sitting, lying, or sleeping or storing, using, maintaining, or placing personal property in the public right-of-way,” allowing the city to sweep homeless encampments near parks, schools, libraries, underpasses, driveways, enterways, and whole sections of the city. At the same time, the city gestured toward an unspecified “street engagement strategy” that would offer interim and permanent housing.

“There’s almost not a single place in the city of Los Angeles, where someone can just be in the world,” Sara Reyes, the executive director of the SELAH Neighborhood Homeless Coalition, told us.

This criminalization will likely increase following the Supreme Court’s decision Grants Pass v. Johnson, which ruled that localities may punish homeless people for sleeping outside, even if there’s nowhere to go. Within hours of the ruling, Los Angeles city councillor Traci Park put forth a motion asking the city to reexamine its existing anti-camping policies.

Prior to Grants Pass, the city was supposed to sweep an individual only if there was a shelter bed available for them. But a 2023 audit of LA’s shelter bed system found that the City’s data was so poor that it was difficult to know how many beds were available or where those beds were. This audit of interim housing bed availability data by Mejia’s office found that there were just 16,100 interim housing beds—while on any given night, about 46,000 Angelenos experience homelessness.

“Counting available shelter beds in a major city is monumentally difficult,” wrote the City of Los Angeles in its brief to the Supreme Court. This fact went on to be cited by Neil Gorsuch in his opinion as to why the court should side with the city of Grants Pass and overturn protections for the homeless.

“Punishing people for sleeping in public spaces when they have nowhere else to go may now be lawful, but it is flat-out cruel and unusual punishment,” Controller Mejia’s office told us. “The City of LA can and must choose better.” In a statement, the office urged the city attorney to not enforce laws that criminalize homelessness while the legislative process runs its course.

“Now that the door is open to criminalizing homelessness, we can expect to see homelessness arrests catapult. And going by the City’s data, we can also expect that we won’t see punitive measures result in meaningful reductions in homelessness or encampments,” the controller wrote.

SELAH’s Reyes echoed the frustration with ongoing criminalization, telling us, “We have not seen a single success story” under the 41.18 ordinance because it misses the problems causing that crisis—“the biggest need is for affordable housing.” In 2023, over 70,000 eviction notices were filed in Los Angeles.

Reyes said that when it comes to solving homelessness, understanding where taxpayer money is going is critical, especially given many initiatives like Urban Alchemy’s are being piloted in real time. Reyes works with a team of volunteers to build relationships and provide outreach with houseless neighbors, and noted the new types of spending from the city look more like a “crisis response” than sustainable long-term solutions, often tasking service providers and case managers with impossible goals.

When the current mayor, Karen Bass, was elected in 2022, she declared a state of emergency on homelessness and launched her own program called Inside Safe. Bass described her program as a “proactive housing-led strategy to bring people inside from tents and encampments for good, and to prevent encampments from returning.” After spending tens of millions on Inside Safe, data from the mayor’s dashboard shows that 2,728 Angelenos have been moved indoors temporarily through the program. (A community audit of Inside Safe put together by mutual aid groups in July reports that 44 people died while part of the program.)

Bass promised to cut LA’s homeless population by 17,000 in her first year; she succeeded on this promise through an assortment of programs. But though Bass campaigned on prioritizing housing, she refused to drop the 41.18 enforcement, and in 2023 1,912 arrests were made for 41.18 violations.

In April 2023, after pushback from constituents about the ordinance, the Los Angeles City Council unanimously ordered a report on 41.18 to assess its effectiveness. The report, which was released nearly a year after its deadline following a leak to journalists at LAist, showed that only two people received permanent housing thanks to the ordinance and that the city spent $3 million on enforcement—excluding the cost of additional policing.

“We’ve known for years that shuffling people from block to block with 41.18 doesn’t work, and now there’s city data proving it,” Council member Hugo Soto-Martínez told the Los Angeles Times in March.

“A sweep is just trying to throw the problem away so we don’t have to look at it,” said Reyes. “If we just spent our money smarter, you would not have a single person who was forced to sleep outside in one of the wealthiest cities in the world.”

In 2022, Mejia received more votes than any citywide elected official in Los Angeles history, and became the first Asian American elected to citywide office. He ran on an anti-establishment platform focused on accountability specifically around LAPD spending and ending homelessness.

We spoke to the controller’s office as they returned, still in suits, from testifying at a federal hearing regarding an independent audit of Los Angeles homelessness programs, including Inside Safe.

In March, after the US District Judge David O. Carter said that the city failed to address needs of homeless residents and misled attorneys, and called the audit, Mejia called for his own audit of Inside Safe. But city officials say the city attorney, Hydee Feldstein Soto, can block the controller from auditing the mayor. An exasperated Judge Carter said of the situation, “We have no accountability at this point. It’s just as simple as that.”

Nearly the same drama is playing out with the Urban Alchemy investigation. Urban Alchemy has stated that it has “taken care of” the hosing incident and conducted their own investigation, Perez at the controller’s office told us. “We all know what happens when an organization assesses and investigates itself,” Perez countered. “Different interests may take the wheel there.”

That’s precisely why the city controller’s office launched its investigation. According to Perez, the city charter provides the controller’s office with the authority to ask a city vendor to prove the services it’s providing are worth taxpayer money

“In this instance,” Perez noted, “that video strongly shows that those services…were not in keeping with the values of the city of Los Angeles.”

When Urban Alchemy refused to provide information related to its contract with the city, the city controller’s office issued a subpoena to force it to comply. In turn, Urban Alchemy filed a lawsuit to block that subpoena.

“Nonprofit organizations working to serve Angelenos don’t deserve to be targeted by powerful elected officials based on personal biases,” Urban Alchemy wrote in a statement.

“We were always happy to provide all relevant documents and information related to the incident in question,” Urban Alchemy told us. “We challenged Controller Mejia’s subpoena in court because it amounted to an overreach of his Charter authority and an abuse of his power. Controller Mejia was trying to use the powers of his office to tarnish the reputation of our organization.”

The city attorney’s office took Urban Alchemy’s side, claiming that Meija does not have the authority to issue that subpoena. She then filed a motion stating that the City Controller’s Office lacked the authority to carry out an inspection at all.

“The charter is clear on the parameters of each office,” the attorney’s office told us. The controller can conduct “financial audits of City Departments and City Offices” and “performance audits of City Departments,” but can only examine individual payments when “a department is found to have inadequate controls or to have abused its authority.”

Perez told us that this was a misreading of the law: “They are dead wrong, and threatening a crucial tool for transparency and accountability.”

Furthermore, on June 5, the city council voted to side with the city attorney, effectively denying the city controller the ability to seek outside legal counsel to fight Urban Alchemy’s lawsuit.

Following that decision, Urban Alchemy dropped the lawsuit against the controller’s office. Apparently, a deal was reached between the nonprofit and the city attorney: Urban Alchemy would provide the documents that the controller had requested and drop the lawsuit.

Ultimately, the documents themselves were not the issue. The fight was about the limits of the controller’s authority. The lawsuit, Urban Alchemy told us, “was intended to ensure transparency by holding accountable those wielding public authority while protecting our organization’s rights against unfounded scrutiny and potential reputational harm.”

“Urban Alchemy will not and cannot open its doors and files to anyone who wants them, regardless of whether they have the power to request them,” the nonprofit wrote in a public comment on June 5.

Perez said he wasn’t sure why the city attorney was “so afraid” of the transparency and accountability. “There is a gentle-person’s agreement” among government officials, he explained, “to mind your lane.” “No one really wants an earnest, full-throated assessment of the work that they do,” he continued, “because their ego, reputation, and money are always tied up in it.”

Despite initially calling the January incident “unacceptable,” Urban Alchemy now says “the video was misleading” and confirms that it reinstated the employee “who was unfairly targeted in social media.” Urban Alchemy told us that it interviewed all involved, including the woman in the video, who “did not feel that any wrongdoing had occurred.” (Urban Alchemy provided no evidence of this.)

Urban Alchemy told us that as a result of its lawsuit, “private entities who provide service to the City can now feel confident that the City Controller does not have the power to harass them.”

But Perez lamented what he sees as a decline in transparency, “When folks can see where their tax dollars are going, they are better judges of whether their government is doing a good job or a bad job. When it comes to the unhoused crisis… I think it’s clear we’re not doing a good job.”

Correction: A previous version of this article stated that in Karen Bass’s first year in office, homelessness increased by 10 percent. In that time, it decreased by 10 percent.

Paige OamekPaige Oamek is a writer and fact-checker based in New York. Their writing has appeared in In These Times, The American Prospect, and other sources.

Rohan MontgomeryTwitterRohan Montgomery is a researcher and writer based in New York. His work has appeared on the BBC and in The New Republic, In These Times, and elsewhere.