You Deserve a 4-Day Workweek

It’s time for Americans to claw their lives back from work.

After six weeks of strikes against General Motors, Ford, and Stellantis, which owns Chrysler, the United Auto Workers announced in late October that it had reached tentative agreements with all three companies and that its members would return to work. The strike, which involved nearly 50,000 workers, resulted in some impressive wins. The workers secured a 25 percent pay increase and future cost-of-living adjustments. They eliminated wage tiers, in which new hires are paid less than long-term employees. They forced Stellantis to commit to reopening a plant in Illinois, something rarely achieved, and guaranteed their right to strike over future plant closures. They ensured that workers at the companies’ electric-vehicle joint ventures could vote to unionize through a card-check system.

But one demand wasn’t met: to shrink workers’ schedules to 32 hours a week at the same pay, with overtime for hours worked beyond that. “Our members are working 60, 70, even 80 hours a week just to make ends meet,” UAW president Shawn Fain said at the start of negotiations. “That’s not a living. That’s barely surviving, and it needs to stop.”

The ambitious demand was likely made as a way to put something on the table that the union could later drop as a concession. But we shouldn’t let it stay on the cutting-room floor. Unions have the wind at their backs, and it’s time to claw our lives back from work.

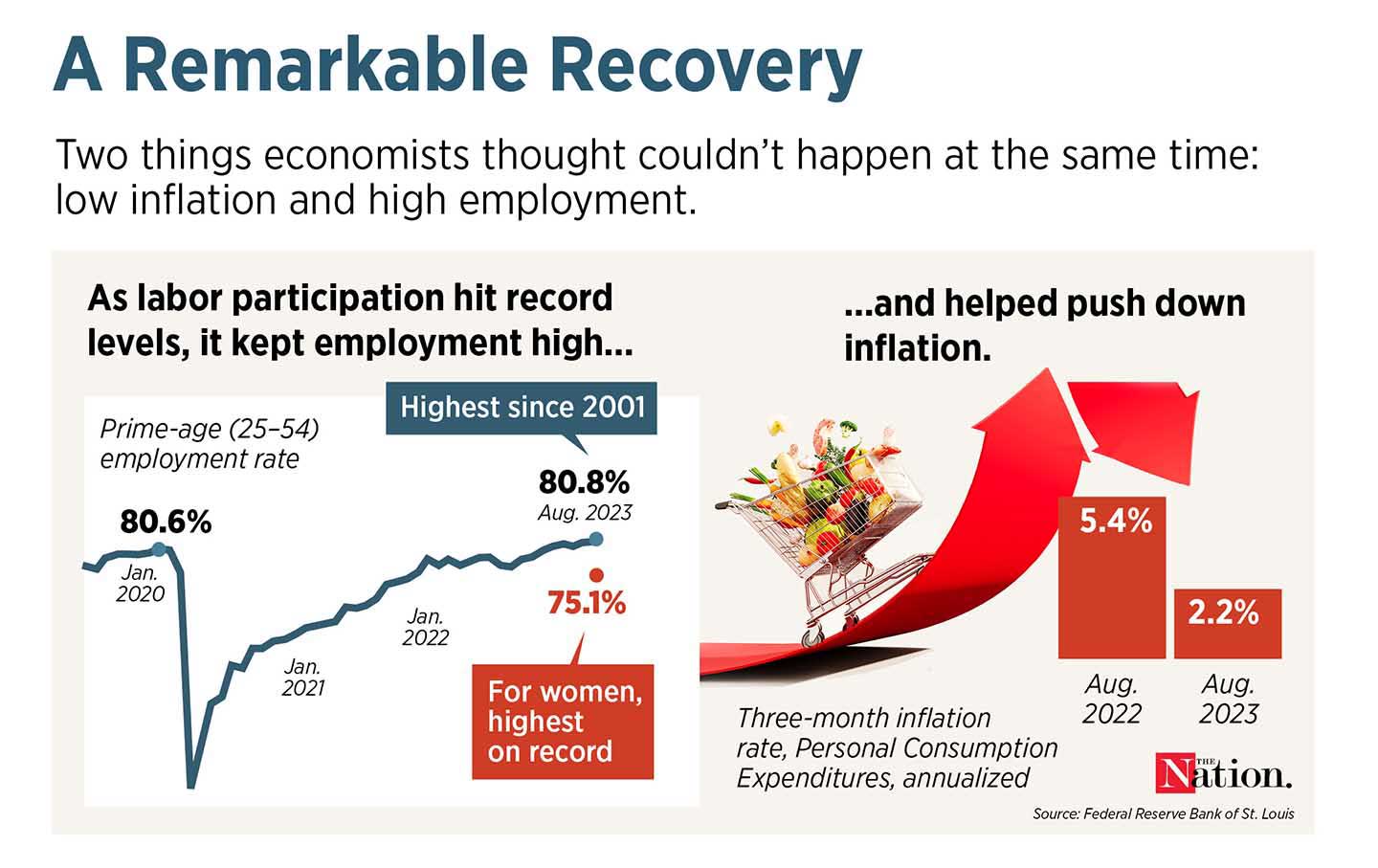

Americans work a lot more than our European counterparts, with a third of us putting in 45 hours or more on the job. For too many Americans, working 9-to-5 is a luxury of a past era. That’s despite plenty of research showing that pushing people to work more hours yields diminishing returns. One study of middle-aged British workers found that cognitive performance dropped when they worked more than 40 hours a week; another that looked at munitions workers in World War I found that their output decreased after 48 hours.

Unions helped bring us that 40-hour workweek, and they’ll need to play a role in making it even shorter. “Eight hours for work, eight hours for rest, eight hours for what you will,” they demanded. At the first May Day protest in 1886, which resulted in the Haymarket massacre, workers chanted: “Eight-hour day with no cut in pay.” Congress passed the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938, which mandates that covered workers be paid time-and-a-half when they put in more than 40 hours per week, but only after decades of mass strikes.

And even then, unions aimed for even less time at work and more time for ourselves. Autoworkers sought overtime pay after 30 hours in the 1940s, and members advocated for shorter workweeks in the UAW’s magazine Solidarity in the 1930s and ’40s. In the 1970s, UAW workers came up with a plan to get some Mondays off. But that demand fell to the wayside, especially as union membership and power began to decline in the 1980s.

Fain isn’t the only labor leader seeking to revive the issue now. In 2019, the AFL-CIO released a report that called for a four-day workweek. And there may be an opportunity to shout this demand more loudly in the future. The UAW contracts would expire at the end of April 2028, and Fain has called on other unions to align their contract expirations with the same date. That way, workers can engage in a mass strike on May Day of that year—possibly even a general strike—thereby putting enormous pressure not only on employers but on lawmakers. There’s a lot of time between now and then to figure out exactly what workers should call for, but there will be no better moment to demand more of our time back from our bosses.

Fain is right. In August, he said, “The greatest resource in this world is a human being’s time.” He described how having to work longer and harder to survive means “less time living life. That means missing Little League games and family reunions. It means less time outdoors, less time traveling, less time pursuing our passions and our hobbies.” Long workweeks deprive us of the time to care for ourselves and our families, and they pose the largest occupational health risks. Shorter weeks, on the other hand, allow people to get more sleep and experience less stress and burnout.

The fight for everyone, no matter where they work, is to return to a society in which people have both enough money to provide for their needs and enough time to eat, sleep, and do what they will. Fighting for higher wages isn’t enough. We must fight for the right to live our lives outside of work, too.

Hold the powerful to account by supporting The Nation

The chaos and cruelty of the Trump administration reaches new lows each week.

Trump’s catastrophic “Liberation Day” has wreaked havoc on the world economy and set up yet another constitutional crisis at home. Plainclothes officers continue to abduct university students off the streets. So-called “enemy aliens” are flown abroad to a mega prison against the orders of the courts. And Signalgate promises to be the first of many incompetence scandals that expose the brutal violence at the core of the American empire.

At a time when elite universities, powerful law firms, and influential media outlets are capitulating to Trump’s intimidation, The Nation is more determined than ever before to hold the powerful to account.

In just the last month, we’ve published reporting on how Trump outsources his mass deportation agenda to other countries, exposed the administration’s appeal to obscure laws to carry out its repressive agenda, and amplified the voices of brave student activists targeted by universities.

We also continue to tell the stories of those who fight back against Trump and Musk, whether on the streets in growing protest movements, in town halls across the country, or in critical state elections—like Wisconsin’s recent state Supreme Court race—that provide a model for resisting Trumpism and prove that Musk can’t buy our democracy.

This is the journalism that matters in 2025. But we can’t do this without you. As a reader-supported publication, we rely on the support of generous donors. Please, help make our essential independent journalism possible with a donation today.

In solidarity,

The Editors

The Nation