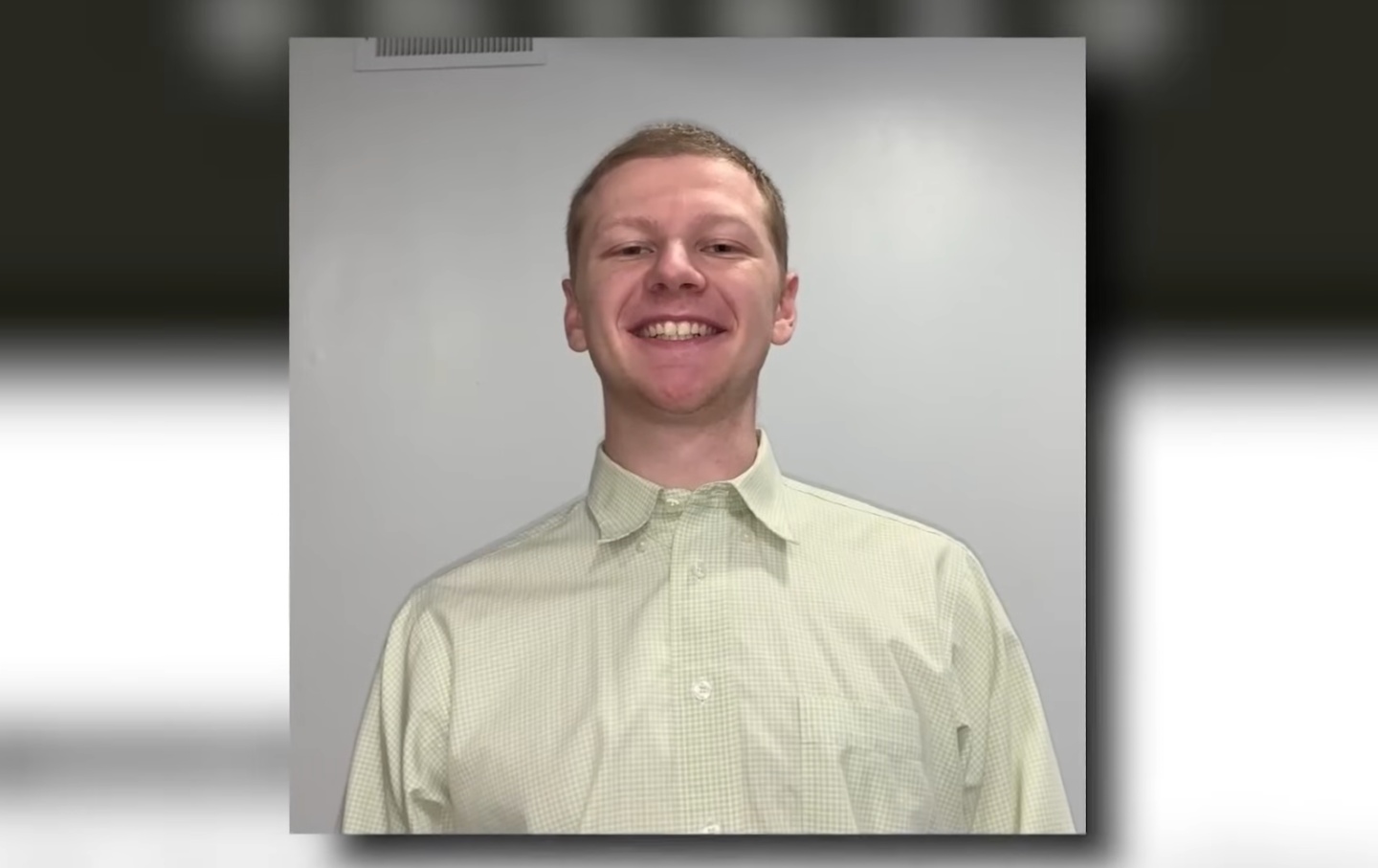

Taking Aaron Bushnell at His Word (and Deed)

The airman who set himself alight on Sunday signed up to sacrifice himself for the greater good—only to discover that he had become an accomplice to evil.

I will leave it to others to discuss the precedents for Aaron Bushnell’s self-immolation outside the Israeli embassy in Washington, from Thích Quảng Đức to Norman Morrison to Mohamed Bouazizi to Irina Slavina to Wynn Alan Bruce. Yes, this has happened before. The world has been a terrible place for too many for too long, and for that reason, the rare few most inclined to feel that terror, to breathe in its ashes, have found no other option but to set themselves on fire in protest. So that others may be forced to breathe in some of those ashes too.

A debate has erupted about how best to interpret Bushnell’s last act. Was it heroic? Pointless? Another opportunity to opine on the need for more robust mental health services. Or to scold those who have dared to take Bushnell at his word. After all, he was anything but inexplicit: “My name is Aaron Bushnell. I am an active-duty member of the United States Air Force. And I will no longer be complicit in genocide. I’m about to engage in an extreme act of protest, but compared to what people have been experiencing in Palestine at the hands of their colonizers, it’s not extreme at all. This is what our ruling class has decided will be normal.”

When someone commits an act like this, and leaves us with words like that, I feel obligated to take the person at their word. And the words couldn’t be more instructive.

Bushnell begins with a pertinent self-identification, as an active-duty member of the United States Air Force. Given the sincerity of his last moment in uniform, it seems he was also announcing his vocation. He was someone who had signed up to sacrifice himself for the greater good, only to discover—as so many of us, myself included, have discovered—that he had signed up for the opposite: to become a willing accomplice to evil.

Bushnell doesn’t spell out the precise nature of his complicity. But the mere mention of his branch of service suffices. The US Air Force has played a significant part in the killing spree in Gaza, assisting with intelligence and targeting. It has helped build Israeli airpower for decades now, and shares the same suppliers of aircraft, missiles, and munitions that have contributed to what the political scientist Robert Pape has called “one of the most intense civilian punishment campaigns in history, [now sitting] comfortably in the top quartile of the most devastating bombing campaigns ever.”

The airman goes on to call the crime by its name: a genocide, an attempt at destroying a people. Their homes and farms and orchards and entire means of subsistence. Their schools and hospitals and universities. Their journalists and professors and teachers and students. The whole of their intelligentsia and their children—so many of their children. An unprecedented number, an almost instant mass killing of children too grotesque to even fathom for more than a second. Their museums and archives and age-old mosques and churches. Hundreds of registered ancient sites. Their past and present and future. Even their cemeteries, their last and only resting place.

Bushnell concedes that his protest is extreme. And yet it pales in comparison to the extremism it is protesting. An extremism not just of everyday death and destruction, but one that qualifies as colonial domination. It is not only that the Israelis or their patron, the Americans, determines which Palestinian lives or dies today or yesterday or tomorrow. It is that they—we—decide how they get to live or die. With or without shelter or food. With or without gainful employment or a loved one or the capacity to move across this or that otherwise invisible, arbitrary line. It is impossible to connote in a single paragraph the depths of this humiliation, of having one’s bare existence leashed to the whims of an undeserving, self-satisfied master. I enforced a related, humiliating relationship in Afghanistan almost a decade and a half ago, as one of many uniformed humiliators. I still haven’t figured out how best to communicate that vice. I don’t have it in me to say Bushnell has found a better way. The implication of that conclusion is too dark. But I do hope he’s done it better.

I’d be remiss without noting Bushnell’s penultimate sentence on this earth, right before the necessary “Free Palestine.” He curses our ruling class for making all this normal. All of it. The spoken and unspoken. The sometimes beautiful and joyful but often needlessly cruel world that’s been built in our name. For our purported security. It’s a plea for the rest of us, those still living. Bushnell’s fellow service members specifically, many of whom entered their service with similar doe eyes. Veterans like myself. (For good or ill, we enjoy a certain discursive power most don’t. And with that, as the cliché goes, comes responsibility.)

I doubt that Bushnell would have wanted us to follow in his footsteps—at least not by dousing ourselves in accelerant before a sad and enraged farewell. But he no doubt was counting on us—and not just us service members or vets—to convey and make use of the sadness and rage in our own ways. In manners that burn and last. Beyond the man-made firestorms in Gaza. Beyond the all-encompassing fire.

Hold the powerful to account by supporting The Nation

The chaos and cruelty of the Trump administration reaches new lows each week.

Trump’s catastrophic “Liberation Day” has wreaked havoc on the world economy and set up yet another constitutional crisis at home. Plainclothes officers continue to abduct university students off the streets. So-called “enemy aliens” are flown abroad to a mega prison against the orders of the courts. And Signalgate promises to be the first of many incompetence scandals that expose the brutal violence at the core of the American empire.

At a time when elite universities, powerful law firms, and influential media outlets are capitulating to Trump’s intimidation, The Nation is more determined than ever before to hold the powerful to account.

In just the last month, we’ve published reporting on how Trump outsources his mass deportation agenda to other countries, exposed the administration’s appeal to obscure laws to carry out its repressive agenda, and amplified the voices of brave student activists targeted by universities.

We also continue to tell the stories of those who fight back against Trump and Musk, whether on the streets in growing protest movements, in town halls across the country, or in critical state elections—like Wisconsin’s recent state Supreme Court race—that provide a model for resisting Trumpism and prove that Musk can’t buy our democracy.

This is the journalism that matters in 2025. But we can’t do this without you. As a reader-supported publication, we rely on the support of generous donors. Please, help make our essential independent journalism possible with a donation today.

In solidarity,

The Editors

The Nation