Is Sports Gambling a Public Health Crisis?

Why a progressive approach might be a national intervention.

“An illness, progressive in its nature, which can never be cured, but can be arrested.” Those words may sound like they describe some neurodegenerative disorder—but in fact, they’re how Gamblers Anonymous defines compulsive gambling. GA hosts more than 1,200 weekly meetings for the estimated 10 million Americans with gambling problems.

If you’re familiar with how other public health crises have been handled in America, you might expect this problem to be ignored by lawmakers. But the truth is, they’re making it worse. In recent years, legislatures across the country have broadly legalized one of the most habit-forming types of gambling: sports betting. Thirty-eight states and the District of Columbia now authorize the practice.

That means it’s currently easier to wager a month’s salary on the NBA Finals than it is to get an abortion.

This wave of legalization has ripped through the country with minimal murmuring from progressives—perhaps a reflection of a broader laissez-faire approach to matters of the personal life on the left. After all, it’s ordinarily a compassionate instinct to let people do what they want with their time and money. And yet a categorical gulf exists between, say, the right to marriage and the freedom to entangle yourself in an inherently exploitative scheme. That’s why the truly progressive approach to sports betting might be a national intervention.

As with more than a few of our current systemic woes, the sports betting craze originates from a Supreme Court decision aimed at safeguarding states’ rights. In 2018, Elena Kagan joined the court’s five conservative justices to overturn a federal sports betting ban. The suit was brought by Democratic New Jersey Governor Phil Murphy over gambling legalization passed by his predecessor, Chris Christie. It took an inspiring bipartisan effort to kick-start this spiral.

The six years since that ruling have seen Americans lose at least $245 billion on sports wagers. And given that rates of gambling addiction are highest among the unemployed, the elderly, and the poor, these losses have been disproportionately borne by those who could least afford them.

Figures like these upend the classic pro-gambling argument that its legalization benefits society by raising revenue for services like public education. According to research on gambling’s economic impact in New Jersey, online casinos have indeed generated hundreds of millions of dollars in taxes. But that influx is canceled out by hundreds of millions of dollars in gambling-related costs, like welfare and homelessness. In reality, vulnerable people are losing more than they’re gaining.

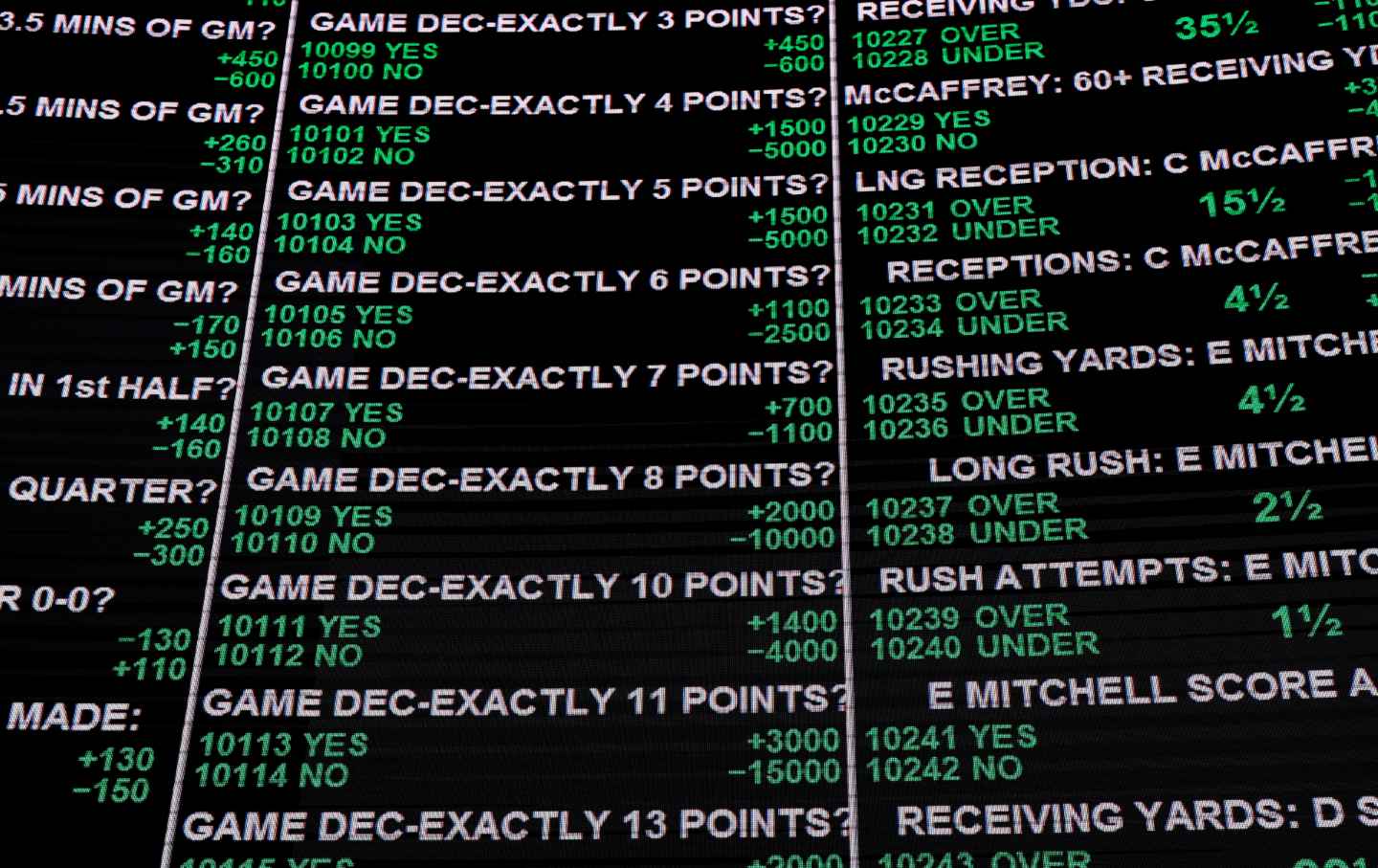

This is by design. And entire industries have conspired to exacerbate the crisis. Tune in to any game today, and you’ll find yourself watching not just the points on the board but also the point spread that broadcasters like ESPN continuously update. Betting magnates have bought up teams: The Adelson family, which operates the multibillion-dollar Sands casino corporation (and bankrolls everyone’s favorite convicted felon president), now owns the Dallas Mavericks. Even the players—and their interpreters—can’t resist the allure of winning big off the field. Sports and sports betting are becoming one and the same.

Maybe most alarming is another convergence—sports betting with smartphones. Valiantly named apps like FanDuel and DraftKings have taken the algorithmic addictions of the perpetual scroll and combined them with the retro fixation of rolling the dice. Dr. Tim Fong, the director of UCLA’s Gambling Studies program, has described these apps as creating a “casino in our pockets.” And they haven’t even fully integrated AI yet.

By far, the most vulnerable are the most online. More and more young people are making wagers in their pajamas, in between classes, and, yes, in the shower. In targeting the youth, betting moguls have successfully future-proofed their industry, if you ignore the fact that their customers will endure an increased risk of suicide for the rest of their lives.

This is not to suggest that we need to take the Carry Nation approach and prohibit sports gambling altogether. But a little regulation could do a lot of good. In Congress, Paul Tonko (D-NY) has urged treating these developments as a public health crisis, the same way the federal government did with cigarettes. His “Betting on Our Future Act” would make glamorous sports betting ads go the way of the Marlboro Man. By banning commercials like the two star-studded spots from this year’s Super Bowl, seen by 123 million people, the bill would stymie the rapid romanticization of a business historically associated with broken kneecaps.

Perhaps predictably, Tonko’s legislation has gone nowhere. And a proposal cosponsored by Senator Richard Blumenthal to fund treatment for gambling addiction hasn’t gathered much momentum, either. Combine that with the Supreme Court’s demonstrated proclivity for blocking federal intervention on this issue, and it may be that, at least in the immediate term, this fight will have to play out in the states—which thus far have been the main drivers of sports betting legalization.

Thankfully, some state lawmakers are beginning to realize they may have gone too fast, too soon. Spikes in the number of young people calling gambling hotlines so concerned Wayne Fontana, a state senator in Pennsylvania, that he introduced a bill banning the use of credit cards for online betting. Local legislators across the country could follow Fontana’s lead. Otherwise, more people will find themselves descending more deeply into more unpayable debt, at a time when loan default rates are already hitting record highs. How many more wagers do we have before it all goes bust?

More from The Nation

“We’re Living Through Hell”: What Trump’s Anti-Trans War Really Means “We’re Living Through Hell”: What Trump’s Anti-Trans War Really Means

When hospitals suddenly stop treatment for trans patients, real people are harmed immediately. “I was sent links to suicide hotlines instead of a prescription,” one person told us...

A Half Century of Failure to Reform the FBI Has Gifted Patel With Alarming Power A Half Century of Failure to Reform the FBI Has Gifted Patel With Alarming Power

Fifty years ago, lawmakers started lifting the lid on the shocking abuses of the new Bureau chief’s most famous predecessor. The trouble is, very little changed.

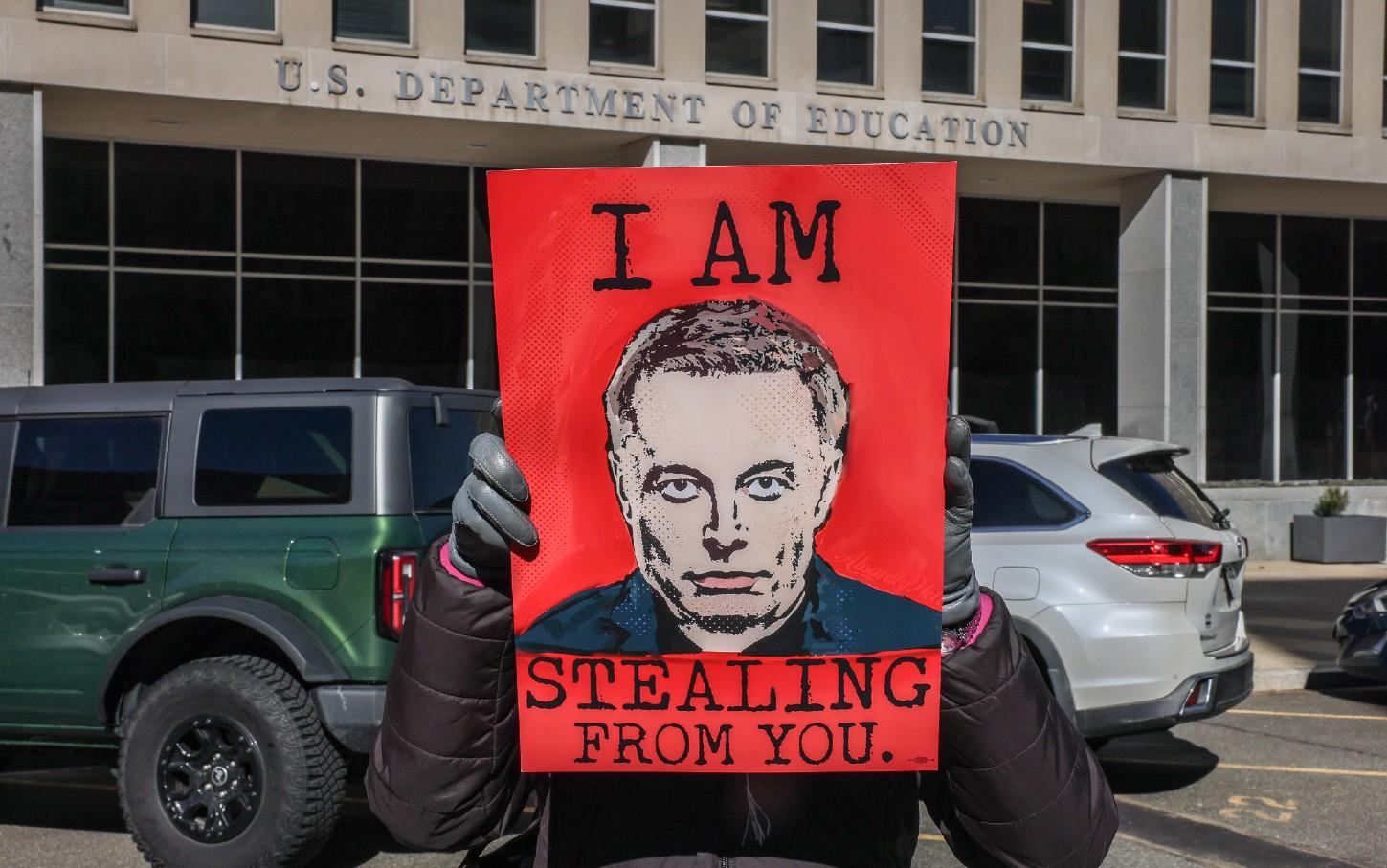

Why Hasn’t Trump Already Closed the Department of Education? Why Hasn’t Trump Already Closed the Department of Education?

Maybe because its support for students is popular with Republicans as well as Democrats. And because cutting that funding would blow a big hole in the budgets of red states.

Shield Laws Are the Fault Line in the Battle Over Abortion Access Shield Laws Are the Fault Line in the Battle Over Abortion Access

New York’s shield law was designed to protect providers mailing medication abortion pills out of state. But a New York provider is facing legal action in Louisiana and Texas.

Javier Milei’s Crypto Scandal Is Part of a Larger Network of Grift and Graft Javier Milei’s Crypto Scandal Is Part of a Larger Network of Grift and Graft

The Argentinian president faces impeachment charges for endorsing a crypto rug pull, via the same network that apparently launched Melania Trump’s memecoin.

The “Teenage Dream” in an Era of Isolation The “Teenage Dream” in an Era of Isolation

Curfew restrictions and the policing of public spaces prevent teens from “getting into trouble.” But to some, it feels like it’s preventing them from getting anywhere at all.