A short history of the origins, uses, and abuses of a long hatred.

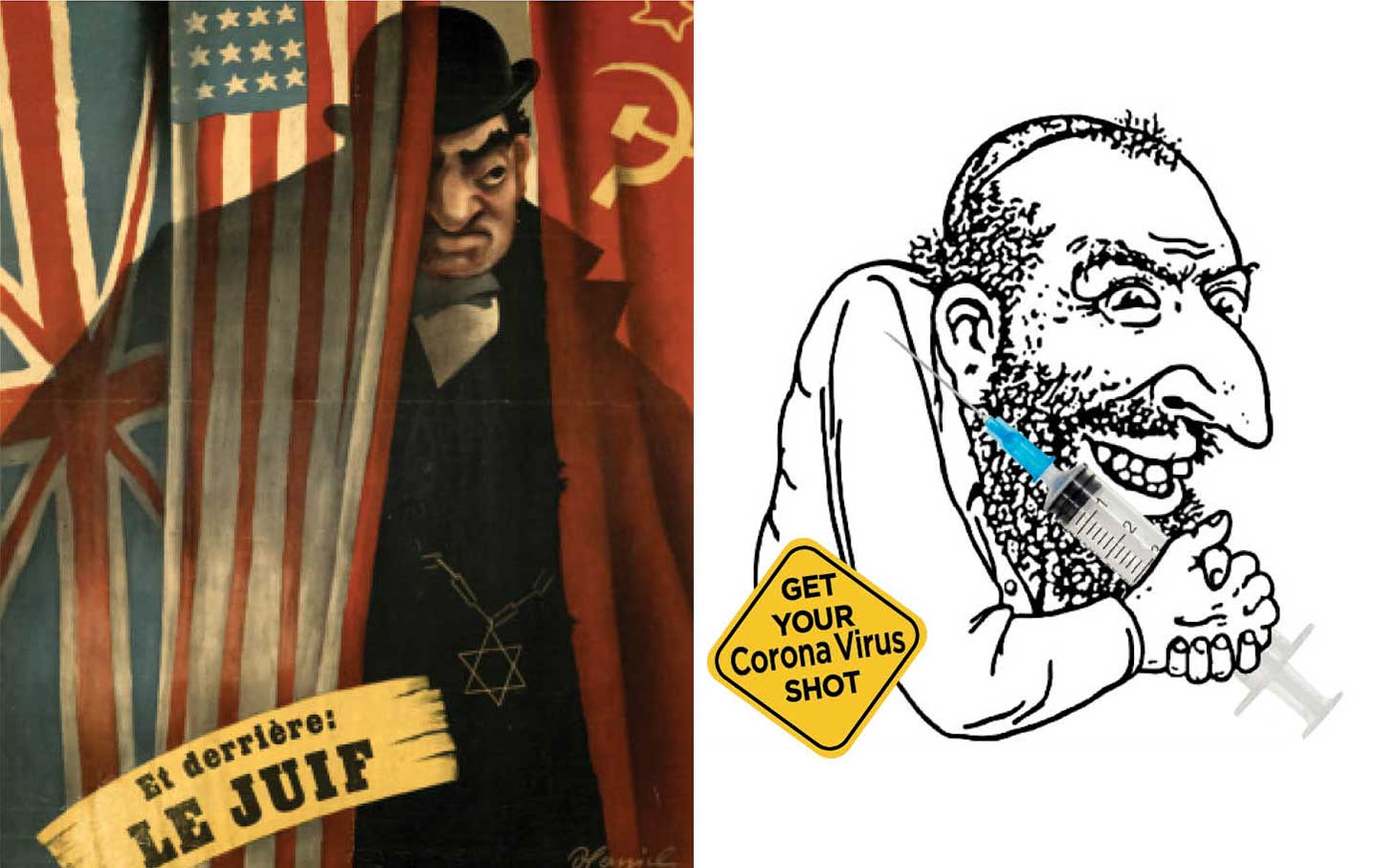

Familiar stereotypes: Left: Nazi propaganda poster from the early 1940s depicts Jews as conspiring to provoke a war with Germany. Right: Just as the Nazis recycled medieval antisemitic tropes, this 21st-century update, featured in a Jerusalem Post story on vaccine resistance, incorporates the visual vocabulary of the Nazi era.(Right: Bruno Hanich, “Behind the Enemy Powers: the Jew,” 1943)

Well before the October 7 Hamas massacre and the ongoing Israeli invasion of Gaza that followed it, the accusation levied against the growing ranks of Israel’s multiple critics, among them liberals and humanists, gentiles and Jews—many of whom had been raised on unconditional love for the country and had idolized and idealized it—was that they were motivated by antisemitism or self-hatred. The link between denying the decades-long oppression of millions of Palestinians and accusing those who pointed it out of antisemitism was made in Israel and then exported to Europe and the United States—wrapped in the underlying allegation that the “nations of the world,” which had stood by while 6 million Jews were murdered, have no right to criticize the Jewish state, which is fighting for its sheer survival. The more Israel veered to the right, and the more the conditions of Palestinian life worsened, the more vehemently Israeli officials argued that any criticism of their actions was nothing more than a scandalous expression of the West’s inherent antisemitism.

The definition of antisemitism by the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance has served handily for this diversion strategy. Conceived as a “working definition” and adopted in 2016, the IHRA document was never meant to serve as the basis for legislation and enforcement. Designed to promote Holocaust remembrance and education, the IHRA definition has instead been seized on as an instrument for silencing criticism, cynically deploying the memory of Nazism’s victims to brand critics of the Jewish state’s increasingly severe breaches of international law as antisemites. This defamation campaign obscures these critics’ professed goals and motivations, not to mention their identities (many are themselves Jewish, and not a few are Israeli).

Scholars of antisemitism, the Holocaust, and Jewish history have repeatedly pointed out the problematic nature of the IHRA definition—which provides 11 examples of what may constitute antisemitic actions or statements, of which seven refer directly to Israel. Examples include denying Jews the right to self-determination, applying standards to Israel not demanded of other nations, accusing Israel of exaggerating the Holocaust, and comparing Israeli policies to those of the Nazis. However objectionable such statements may be, they are not in and of themselves antisemitic: Critics, including many Israelis, have long argued that Israel has instrumentalized the Holocaust for political ends; supporters of Zionism have often argued that Israel should be “a light unto the nations” and therefore held to higher standards; many Jews around the world have rejected Zionism for theological or ideological reasons; and comparisons of either Israeli or Palestinian actions to those of the Nazis are commonplace in Israel—even among self-described Zionists. For this reason, alternative definitions have been offered, such as the Jerusalem Declaration on Antisemitism and the Nexus Document, which take pains to make distinctions between antisemitism and criticism of Israel.

Nonetheless, largely in response to the growing protest movement on American university campuses against Israel’s brutal war in Gaza, the view of antisemitism encapsulated in the IHRA definition has worked its way up to the highest levels of US policymaking. On May 1, the House of Representatives overwhelmingly passed the Antisemitism Awareness Act, which adopts the IHRA definition—a move that threatens free speech throughout the country. A few days later, at a ceremony of remembrance for victims of the Holocaust, President Biden denounced what he termed a “ferocious surge” in antisemitism on college campuses in the United States and around the world following the October 7 attack—thus endorsing the false conflation of criticism of Israel’s indiscriminate destruction of lives and property in Gaza with antisemitism. Just as troubling, Biden seems to have endorsed the argument made by Israeli politicians and many of the country’s right-wing defenders that opposition to Zionism—or at least the destructive, racist, Jewish-supremacist Zionism represented by Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and his extremist government—is equivalent to antisemitism. Among other things, this is tantamount to saying that hundreds of thousands of anti-Zionist or non-Zionist ultra-Orthodox Jews (Haredim) around the world—including some prominent non-Zionists in Israel’s own government—are also antisemitic.

Judeophobia, now commonly referred to as antisemitism, has a long and vile history. In the pagan world, Jews were singled out because of their insistence on worshipping only one god, for their self-identification as a chosen people—and because they were also a rebellious, independent people.

Under Greek rule, Jewish elites were increasingly Hellenized, but as tradition has it, in 167 bce, the Maccabees rebelled against rule by the Seleucid empire, clearing the Temple in Jerusalem of what they perceived as gentile filth. The Roman takeover of Judea in 63 bce brought the Jews under the rule of the most powerful political and military entity of the ancient world—a vast empire that tolerated the different religions and customs of its numerous provinces if they accepted Rome’s political authority. Yet instead of accommodating to Roman rule, the Jews again rebelled. This was a fatal move for Jewish existence in Judea.

The Great Jewish Revolt of 66–73 ce ended with the destruction of Jerusalem and the Second Temple and the eventual fall of Masada. It was here that the Zealots—as the rebels on that isolated hilltop called themselves—made their last stand against the empire. Like the extremists in the current Israeli government, the Zealots had no interest in politics or compromise. For them, the only alternatives were victory or death: In their fight with the Romans, the choice was clear, and as the Romans breached their defenses, they ended their lives by their own hands, murdering their wives and children—and sending the Jews into 2,000 years of exile in the name of an insane, profoundly un-Jewish messianic faith. At least this is what we are told by the Hellenized Jewish general turned Roman collaborator and historian Flavius Josephus—a story that remained suppressed and forgotten for many centuries, only to be revived by the Zionists as the epitome of Jewish nationalism and martyrdom. As for autonomous Jewish life in Judea, that came to a final end following the disastrous failure of the Bar Kokhba revolt of 132–136 ce.

The destruction of the Temple and the exile of the Jews created a new Judaism. Even before these traumatic events, vast numbers of Jews were living in such cities as Alexandria and Rome. As the Jews spread into Europe in the footsteps of the Roman legions, a new Jewish civilization developed in Europe—where most Jews lived for the next two millennia. These diaspora Jews had no time for the suicidal passion of the Masada zealots. Their ethos was one of accommodation and survival as a minority in an alien environment. That environment, meanwhile, cast off paganism and adopted Christianity—originally a Jewish sect claiming to be led by the Messiah, the Son of God, but one that, unlike the Judaism from which it had emerged, sought to bring all of humanity under its spell. As the Jews waited for their messiah far from their promised land, Christianity spread—or was brutally imposed—eventually reaching the farthest corners of Europe and beyond.

Jews and Christians had an ambivalent relationship. For Christians, the Jews had denounced Jesus and called for his crucifixion; but they were also witnesses of that cardinal event and the most critical targets for conversion. For Jews, Christianity was a false outgrowth of Second Temple sectarianism, which posed a clear and present danger to the continuation of Jewish faith, tradition, and community. At the same time, Christian society came to depend on Jews for tasks forbidden to Christians—not least usury, or moneylending—but it also feared and despised Jews as corrupt, filthy, and demonic. Jewish communities interacted with Christians in commerce, craftsmanship, manufacturing, and estate management, but they despised gentiles as ignorant and boorish, and they feared both their power and their potential to lure Jews away from their faith. When crises struck, such as the Black Death, or when adventures beckoned, as was the case during the Crusades, Jews were liable to be slaughtered. Entire European Jewish communities could be expelled, as happened in England in 1290 and in Spain in 1492. At other times, not least in Poland, Jews thrived as servants of the nobility, financiers of rulers, or merchants and shopkeepers in Christendom’s expanding towns and cities. Outside of these occupations, the Jews often wanted to keep to themselves—and the Christians just as frequently wanted to stay away from them.

There was also a darker, mystical—not to say diabolical—aspect to this relationship. As early as the 12th century, Jews came to be accused of ritual murder, especially on Passover—when Jews are instructed to drink four glasses of wine and to eat unleavened bread. According to this increasingly widespread myth, Jews required the blood of Christian children to make matzos or for other ritual purposes (possibly echoing the Christian belief that in the Eucharist, Christ’s flesh turns into bread and his blood turns into wine). This “blood libel” thus added an additional magical layer to the ongoing theological animosity and socioeconomic resentment against Jews, lasting well into the modern era.

But just as the Jews of medieval Prague brought the golem into the world—a giant made of mud intended to protect them from their foes, which then turned against its makers—so the modern era allowed Jews, for the first time in two millennia, to leave the ghetto and join the rest of society. It was this second Exodus that brought “antisemitism” into the world. A term coined in the 1870s, antisemitism differed from age-old Judeophobia in that it was a response to Jewish emancipation rather than to Jewish alienness. Emancipation (the granting of equal rights to Jews)—especially when accompanied by assimilation (the transformation of Jews into Europeans in their outward appearance, norms, social conventions, and relationships)—seemed to pose a threat to both Jews and Christians. For Jews, emancipation potentially spelled the end of a separate Jewish identity, deeply rooted as it had been in community, faith, and strict boundaries vis-à-vis Christian society. For Christians, the multiple threats of modernity—rapid urbanization; the disintegration of patriarchal, religious, and communal authority; the loss of traditional professions in the face of industrialization; and the creation of a new, impoverished, regimented, and alienated working class—came to be associated with the entry of Jews into mainstream society and their perceived domination of precisely those slots that modernization had created: mass production, chain stores, new media such as publishing and film, and international banking. Assimilation also made it harder to keep track of who was a Jew.

Donald Trump’s cruel and chaotic second term is just getting started. In his first month back in office, Trump and his lackey Elon Musk (or is it the other way around?) have proven that nothing is safe from sacrifice at the altar of unchecked power and riches.

Only robust independent journalism can cut through the noise and offer clear-eyed reporting and analysis based on principle and conscience. That’s what The Nation has done for 160 years and that’s what we’re doing now.

Our independent journalism doesn’t allow injustice to go unnoticed or unchallenged—nor will we abandon hope for a better world. Our writers, editors, and fact-checkers are working relentlessly to keep you informed and empowered when so much of the media fails to do so out of credulity, fear, or fealty.

The Nation has seen unprecedented times before. We draw strength and guidance from our history of principled progressive journalism in times of crisis, and we are committed to continuing this legacy today.

We’re aiming to raise $25,000 during our Spring Fundraising Campaign to ensure that we have the resources to expose the oligarchs and profiteers attempting to loot our republic. Stand for bold independent journalism and donate to support The Nation today.

Onward,

Katrina vanden Heuvel

Editorial Director and Publisher, The Nation

“The Jews are our misfortune”—a slogan coined by the late-19th-century German historian Heinrich von Treitschke—became the rallying cry of the old middle class, whose existence was threatened by modernization. These were not the easily identifiable traditional Jews, with their beards and caftans, but men and women who looked and spoke and behaved like the rest of society. Yet underneath their “European” guise, it was feared, lurked the same conniving Jew, who was now associated with all the ills of both capitalism and its mortal enemy, communism, since the Jew’s supposed goal was to undermine European (i.e., Christian) society and lord over it, as one of the first and perhaps most successful modern pieces of fake news, the forged Protocols of the Elders of Zion, purported to prove.

Accompanying this adaptation of premodern anti-Jewish imagery, prejudices, and phobias to the politics and anxieties of modernity, a new “scientific” racism lent an apparently scholarly respectability to the division of humanity into separate races—with some races viewed as superior to others. In this newly conceived racial hierarchy, Jews were allotted a special place as not merely physically and morally inferior to European races—most prominently the Aryan or Nordic types—but also as being particularly insidious and dangerous. Since innate racial qualities could not disappear through assimilation, some scientists, aligning themselves with political ideologues, called for a regime of “racial hygiene” that would prevent miscegenation and thus the pollution of the higher races, not least by sinister “semites.” It was from these sources that Nazi ideology eventually emerged.

One response to antisemitism, the modern Judeophobia, was Zionism. Born in an era of growing ethnonationalism—the idea that ethnic groups should form into nations and that nations should constitute themselves into states—Zionism concluded that Jews were not only the members of a religion or an ethnic group but a nation, which deserved to eventually rule over itself in its own land. The Jews, it argued, had become an abnormal people, living everywhere as a despised minority, destined to either endure their neighbors’ violence or be assimilated by them. Therefore, they had no choice but to “normalize” their existence in a land of their own, where they would constitute the majority and rule over themselves. Zionism, in other words, was the product of late-19th-century East-Central European nationalism, from which it borrowed many of its attributes, and of the new antisemitism that targeted precisely those Jews who wished to become part of European society and join the nations in which they lived. If the Jews were to be designated the “misfortune” of such newly declared nations as Germany, then they had better create for themselves their own, exclusive nation-state.

The final—and, at the time, seemingly incontrovertible—argument for the necessity of a Jewish nation-state came in the wake of the Holocaust. The Jewish masses that the Zionists had hoped to bring to Palestine to make it into a majority-Jewish state had been murdered. The indigenous Arab population of Palestine, who in turn were coming to see themselves as a Palestinian people who deserved their own state, increasingly resisted the Zionists pouring into the land under the appealing—but evidently false—slogan of bringing a “people without a land to a land without people.” The resulting 1948 war did create a majority-Jewish state—not by multiplying the Jewish population 10-fold through immigration, but by expelling most of the Palestinian population from what became the state of Israel.

Israel was supposed to solve the “Jewish Question” once and for all: a state where Jews would enjoy sovereignty, security, and prosperity; where they would join the international community as equal partners; and where they could “normalize” their existence. No longer a people of luftmenschen—engaging in “air businesses” such as peddling and money exchange, disconnected from the soil—they would become farmers and soldiers, policemen and construction workers, a new breed of Jews, healthy in body and spirit. In a word, “sabras.”

Despite ending two millennia of exile, as Zionism would have it, Israel never managed to normalize Jewish existence. Having sought to become a majority-Jewish state at any price, it paid the price of creating a vast Palestinian refugee crisis that it still refuses to address. Having enjoyed a Jewish majority for the first two decades of its existence, its greed for additional territory transformed it after 1967 into a country in which half of the population are Palestinians, none of whom have equal rights—most of them with no rights at all. Having sought to provide a secure home for Jews, it has become the most unsafe spot for Jews on earth. Having claimed to be the final answer to antisemitism, Israel is now the best excuse for antisemites around the globe—a nation whose addiction to violence and oppression, reliance on great powers and financial clout, and constant invocation of the horrors of the Holocaust as an excuse for untethered brutality against Palestinians is making even its erstwhile supporters shrink from it in discomfort, if not horror and disgust.

In view of this history, what led to Biden’s reference to a “ferocious surge” in antisemitism on college campuses? In part, this has doubtless been driven by pressure from conservative Jewish nationalist donors and supporters—many of whom have close ties to the Israeli right, even though in the United States they may be associated with liberal causes or institutions (such as real estate billionaire Barry Sternlicht, a major donor to my own institution, Brown University, who withdrew his support after Brown’s president, Christina Paxson, reached a landmark agreement with protesting students). Even at universities proclaiming diversity, open-mindedness, and a commitment to academic freedom, such donors—as well as the university presidents who depend on them—prefer that the police be called in to silence those objecting to the atrocities being perpetrated by the Israel Defense Forces.

But I believe that an even more important factor behind Biden’s rhetoric is a total misunderstanding of what antisemitism actually is—and how it can and must be resisted. To be sure, antisemitism had existed for decades before the Jewish state was established and would not disappear if Israel ceased to exist. But what’s currently giving license to real antisemites is Israel’s policies concerning not just the war in Gaza, but the long-term occupation and oppression of Palestinians more broadly. These policies are also converting supporters of the state—even those who once loved and cherished it—into determined opponents in the name of precisely the same values that were supposed to have led to Israel’s creation: liberty, dignity for the oppressed, resistance against the oppressor, solidarity with the victims, and determined opposition to unbridled violence and the killing of innocents. Israel was created in the wake of the Holocaust under the banner of “Never again.” This is what President Biden should have said at the Holocaust ceremony: “Never again” means never again killing innocent Jews, as was perpetrated by Hamas, just as much as it means never again killing innocent Palestinians, as the IDF has done in Gaza, including thousands of Palestinian children. Never again to wanton, callous murder. Never again to impunity. This must always be the right policy against antisemitism as against any other type of racism and bigotry. And just as important, once the killing ends, as end it must: punishment for the guilty, Jew and gentile alike.

Omer BartovOmer Bartov is Samuel Pisar Professor of Holocaust and Genocide Studies in the Department of History, and Faculty Fellow at the Watson Institute for International & Public Affairs, at Brown University.