Save Us All From The Atlantic’s Protest Coverage

The magazine has unleashed its top writers on the Palestine student movement. The results have been as dire as you might imagine.

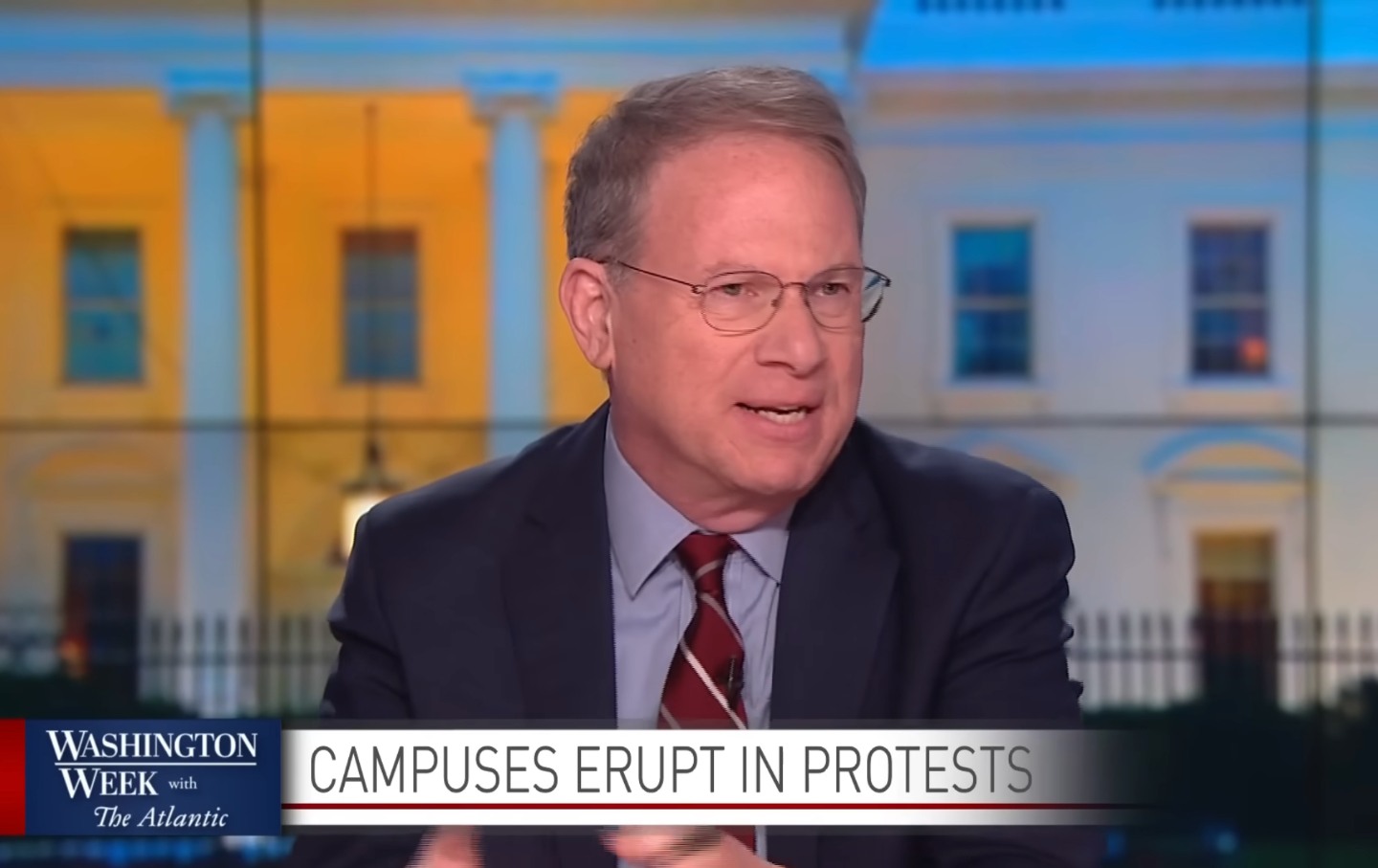

The Atlantic’s editor-in-chief Jeffrey Goldberg.

(PBS)

During the wave of moral panics and racial paranoia that crashed through the 1990s, one media-powered social myth that stuck was “wilding.” The term first surfaced in earnest to characterize the alleged sociopathic, thrill-seeking conduct of the five Black and brown teenagers whom the police and the press falsely identified as suspects in the 1989 Central Park jogger case—the same episode, as it happened, that launched Donald Trump’s career as a race-obsessed demagogue when he took out full-page newspaper ads to demand that New York State bring back the death penalty so it could expedite the lynching of the Central Park Five.

“Wilding,” like its propagandistic relative the “superpredator,” was a device to stigmatize the young—and particularly the non-white young—as blank-eyed engines of menace and violent intimidation, dealing out mayhem on a mere whim, like extras in A Clockwork Orange. And like superpredators, the disciples of wilding turned out to be a complete media fabrication—one that, though it failed to provide any evidence that monstrous Black kids were waiting around every corner, said a great deal about the self-involved outlook and ugly animuses of the American pundit class.

That same loathing of young people is now fueling media dispatches about a different sort of youth deviationism—the pro-Palestinian protests that have spread from Columbia University to campuses across the country over the past three weeks. And the old narrative precepts of wilding have been duly brushed off and revived—most notably in the country’s preeminent organ of alarmist elite consternation, The Atlantic.

Since the Columbia demonstrations began last month, The Atlantic has repeatedly portrayed them as an irrational, militant, and perverse secession undertaken by a coddled caste of woke activists enforcing Leninist discipline among themselves while intimidating dissenters. Only where earlier wilders were smeared as the demons of the underclass, these Ivy League wilders are held to be antisemites, pandering to the ugliest stereotypes advanced not only by Hamas and other jihadist supporters of Palestinian liberation but by the Nazis themselves. Thus, for example, when Columbia protesters occupied Hamilton Hall—which they rechristened Hind’s hall in recognition of a 6-year-old girl killed under Israel’s mass slaughter of civilians in Gaza—and broke some windows in the process, Atlantic writer Caitlin Flanagan, a random search engine for culture-war hypertrophy, repaired to her Twitter account to proclaim the occasion “Kristallnacht on the Hudson,” and demand the students’ expulsion.

This Trumpian thirst for vengeance had been a steady feature of Flanagan’s plainly demented tweeting on the protests; she had also demanded that Columbia faculty showing support for the protesters be arrested, and noted how much she’d prefer to hang out with the cops summoned to thwart the protests rather than the arrogant trust-funders leading them. Lest this leave her posture a tad too ambiguous, Flanagan celebrated the coda to the NYPD’s separate shock-troop assault on protests at the City College of New York—in which the cops took down a Palestinian flag hoisted by the protesters and replaced it with an American flag—thusly: “The great NYPD gives us an Iwo Jima for the 21 century. This land belongs to you and me.” Never mind, of course, that Woody Guthrie, who composed that latter sentiment, derided cops on principle (“When you die and go to heaven,” one of his lyrics went, “you won’t find no policemen there”) or that he performed on a guitar bearing the legend “This machine kills fascists.” Flanagan was projecting her melodramatic outrage onto the vast American citizenry, presumed to be mortally offended by the reminder that its government and institutions of higher education are complicit in the untrammeled massacre of civilians in the Occupied Territories. She was also reveling in the sight of young people being brought to heel by the state. She was, in other words, reprising the core refrain of the wilding myth.

And she’s far from alone at this estimable gatekeeper of centrist opinion. Atlantic staff writer Michael Powell filed a dispatch from Columbia in the wake of the police siege, eagerly cataloging every unseemly or extreme moment he could find. And that’s not all: Nearly all the protesters at the encampment, Powell wrote, had “wrapped their faces in keffiyehs and surgical masks” (here I registered a brief shock at the news that my own stubborn adherence to public masking to prevent the further spread of Covid was evidently a gesture of solidarity with terrorists). Among the disgruntled, he went on to note, the

rhetoric grew ever angrier. Columbia, a protester proclaimed during a talk, was “guilty of abetting genocide” and might face its own Nuremberg trials. President Minouche Shafik, another protester claimed, had licked the boots of university benefactors. Leaflets taped to benches stated: palestine rises; columbia falls.

The darkness continued to gather:

On campus, as the end loomed, a diminutive female student with a mighty voice stood before the locked university gates and led more than 100 protesters in chants. “No peace on stolen land,” she intoned. “We want all the land. We want all of it!”

Powell’s report is, of course, headlined, “We want all of it!” with the helpful explanatory subhead, “The Columbia student protesters backed themselves into a corner.” The photo, which Caitlin Flanagan no doubt approved of, shows masked protesters in the occupied building gesticulating over a “Hind’s Hall” banner opposite a shattered window.

Easing into armchair historian mode, Powell patiently informed Atlantic readers of the exotic sources of all this unhinged anger and “maximalist rhetoric.” “For more than a decade now,” he wrote,

we’ve lived amid a highly specific form of activism, one that began with Occupy Wall Street, continued with the protests and riots that followed George Floyd’s murder in 2020, and evolved into the “autonomous zones” that protesters subsequently carved out of Seattle and Portland, Oregon. Some of the protests against prejudice and civil-liberties violations have been moving, even inspired. But in this style of activism, the anger often comes with an air of presumption—an implication that one cannot challenge, much less debate, the protesters’ writ.

Where to begin? First off, if you’re tracing the alleged new quasi-authoritarian style of campus protest to Occupy Wall Street, that view of things runs completely counter to the criticisms centrists leveled against the movement in real time; they complained not that it was rife with know-it-all partisans presumptively allergic to debate and inquiry, but that it was altogether too participatory—so much so that Occupy didn’t produce a stable and consistent list of demands from a leadership that wanted to tackle most every feature of our oligarchic political economy at the same time. (And speaking of which, Occupy was not “against prejudice and civil-liberties violations”—it was against the gangster-style appropriation of wealth exposed by the 2008 meltdown and its aftermath. Similarly, the BLM protests of 2020 only engaged such questions as a function of its effort to redress the institutional abuses that perpetuate racialized and lethal law enforcement practices. This might come off as a pedantic point, but it is actually important, in mounting critiques of methods and tactics, to render a protest movement’s goals accurately.)

It’s true that some extreme actors, messages, and slogans have surfaced at these most recent protests—just as it’s true that cries of “Zionist!” and other sloganeering at the anti-Gaza encampments can veer close to targeting Jewish students on the basis of their identity. Such abuses should be properly curtailed and called out—yet it’s striking, in Powell’s own reporting, how little his informants profess any identity-based discomfort at the protest. Rory Wilson, a Columbia senior, reported a brief physical altercation with a protester, but didn’t even take that especially personally: “Some have lost families and loved ones,” he told Powell. “I understand their anger and suffering.” It’s hard to square that firsthand account with an alleged atmosphere of rage and dogmatic intolerance.

It’s equally puzzling that Powell’s editors sent him back to the scene of the protests in the first place, since just a week earlier, he’d filed another piece in and around the Columbia encampment, titled, with the same telltale forensic assurance, “The Unreality of Columbia’s ‘Liberated Zone.’” His verdict was similarly dismissive: “What I witnessed seemed less likely to persuade than to give collective voice to righteous anger. A genuine sympathy for the suffering of Gazans mixed with a fervor and a politics that could border on the oppressive.”

Where was this oppression-bordering rancor, exactly? It’s true that one member of the protest’s security corps of security liaisons oafishly announces, “Attention, everyone. We have Zionists who have entered the camp!” and a protest leader rudely talks over a trio of Jewish Columbia students asking to know why they’ve been asked to leave the encampment. But here, too, the victim doesn’t seem to be deeply distressed—“They’re Columbia students, too nerdy and worried about their futures to hurt us,” she told Powell.

For his part, Powell was mostly put off by the failure of students to speak with him: “I found most students distinctly non-liberated when it came to talking with a reporter.” (He doesn’t note that much of this distrust is due to past efforts to dox protesters, together with didactic and singularly hostile coverage from mainstream outlets such as, well, The Atlantic.) After reviewing some reports of Jewish students’ being unfairly targeted by protesters’ rhetoric, Powell somewhat ruefully notes that “the students I interviewed told me that physical violence has been rare on campus. There have been reports of shoves, but not much more.”

Once more, the designated wilders are showing a frustrating aversion to wilding behavior; so our campus-protest correspondent adjourns instead to Columbia’s outlying neighborhood.

The atmosphere on the streets around the campus, on Broadway and Amsterdam Avenue, is more forbidding. There the protesters are not students but sectarians of various sorts, and the cacophonous chants are calls for revolution and promises to burn Tel Aviv to the ground. Late Sunday night, I saw two cars circling on Amsterdam as the men inside rolled down their windows and shouted “Yahud, Yahud”—Arabic for “Jew, Jew”—“fuck you!”

It surely can’t be news to Powell, whose Atlantic author’s biography touts his past experiences as a cab driver and a tenant organizer, that the streets of New York can harbor ugly tribal bigotries and profane and unhinged revolutionary outbursts. Still, our correspondent soldiers on, and eventually finds his quarry on a bench near the encampment: a long-matriculated Columbia masters student named Danny Shaw, who had taught for 18 years at the John Jay College of Criminal Justice before getting dismissed for incendiary anti-Israel pronouncements on social media. He’s now among “the rotating cast of speakers at late-night seminars in the liberated zone.” After they part, Powell looks around the night-quiet grounds of Columbia and delivers his tailor-made envoi: “I could not shake the sense that too many at this elite university, even as they hoped to ease the plight of imperiled civilians, had allowed the intoxicating language of liberation to blind them to an ugliness encoded within that struggle.”

Well, yes, you could shake that sense, actually. As it happens, reporting around the encampment has been detailed, plentiful, and close-in, with scant confirmation of encoded uglinesses not perpetrated by older hangers-on who no longer sport Columbia affiliations. Columbia’s radio station WKCR furnished illuminating and indispensable real-time reporting from the encampment and the occupied Hamilton building; so did correspondents with The Nation’s own student-journalist outfit StudentNation. And at other universities, such as Brown and Wesleyan, student activists reached productive accords with the institutions’ administrators, giving the lie to Powell’s pet thesis that the brittle dogmatism of student protests is dangerous and self-defeating.

Indeed, while it’s very difficult to get an accurate gauge of a protest movement’s guiding ethos in the heat of confrontations with authority, the demonstrations at Columbia and elsewhere don’t seem to conform to the preferred media image of belligerence, puritanical scorn, and revolutionary self-criticism; the students seem, rather, to have exerted a level of self-discipline that’s exceedingly difficult to sustain, particularly under the threat of expulsion, banishment from campus housing, arrest, and police assault.

None of this will deter the Ahab-like determination of their interlocutors at The Atlantic, however. From the deep-thinking history desk comes a rumination by George Packer on the unlovely legacy of the most famous student occupation of a Columbia building, at the height of anti-war student activism in 1968. Packer sees the long shadow of the 1968 confrontation in every lamentable feature of the anti-Israel protest, finding that

the current crisis brings a strong sense of déjà vu: the chants, the teach-ins, the nonnegotiable demands, the self-conscious building of separate communities, the revolutionary costumes, the embrace of oppressed identities by elite students, the tactic of escalating to incite a reaction that mobilizes a critical mass of students. It’s as if campus-protest politics has been stuck in an era of prolonged stagnation since the late 1960s. Why can’t students imagine doing it some other way?

Well, at least he’s not blaming it all on Occupy Wall Street. Still, one might far more profitably ask why commentary about contemporary student protest—of which Packer’s essay is tediously representative—remains mired in the explanatory templates of the 1960s. The American university, after all, has undergone a massive sea change in the intervening five decades, from treating students as scholars and critics in the making to a donor-driven model of universities as glorified private equity funds, and students marshaled to the side as deferential, grasping clients.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →Packer sees none of this; like other Boomer-age partisans of political debate, he can see the world only through the lens of his own generation’s mighty and tectonic influence. In sizing up the longer-term achievements of Columbia’s sit-down action, he writes that “the most lasting victory of the ’68ers was an intellectual one. The idea underlying their protests wasn’t just to stop the war or end injustice in America. Its aim was the university itself—the liberal university of the postwar years, which no longer exists.” The fallout is as baneful as it is omnipresent:

Ideas born in the ’60s, subsequently refined and complicated by critical theory, postcolonial studies, and identity politics, are now so pervasive and unquestioned that they’ve become the instincts of students who are occupying their campuses today. Group identity assigns your place in a hierarchy of oppression. Between oppressor and oppressed, no room exists for complexity or ambiguity. Universal values such as free speech and individual equality only privilege the powerful. Words are violence. There’s nothing to debate.

As a result, Packer writes, Columbia has connived to create its own nemesis with the Gaza protests:

The muscle of independent thinking and open debate, the ability to earn authority…has long since atrophied. So when, after the October 7 Hamas attack on Israel, Jewish students found themselves subjected to the kind of hostile atmosphere that, if directed at any other minority group, would have brought down high-level rebukes, online cancellations, and maybe administrative punishments, they fell back on the obvious defense available under the new orthodoxy. They said that they felt “unsafe.” They accused pro-Palestinian students of anti-Semitism—sometimes fairly, sometimes not. They asked for protections that other groups already enjoyed. Who could blame them? They were doing what their leaders and teachers had instructed them was the right, the only, way to respond to a hurt.

Sigh. Whereas Michael Powell was driven out to Amsterdam and Broadway to track down suitable wilding souls, Packer has tunneled his way back to the Weather Underground’s Days of Rage. One would never know from such agons that the most popular majors among American college students by a wide margin are business administration and healthcare—and that state universities that enroll far more students than Columbia have been shedding the humanities departments allegedly inculcating such woke-ist groupthink at an astonishing clip. But never mind: Packer is brandishing his predetermined thesis with the same confident élan that Powell brought to his identical takeaway: “Elite universities are caught in a trap of their own making, one that has been a long time coming.”

What’s striking is that, for all The Atlantic’s elite lamentations over the Pravda-style uniformity of thought cultivated in the ivied precincts of our prestige universities, no party line is more undeviating on the import of student protests than The Atlantic’s own. (This, mind you, is the sort of publication that reserves the brave, transgressive headline “The Blindness of Elites” for a rapt profile of professional woke-defier Walter Kirn by… professional woke defier Thomas Chatterton Williams, making the elite self-involvement of George Packer seem positively stoic by comparison.)

The magazine’s editors have even managed to find an actual college student to parrot it. But its campus perestroika correspondent turns out to be Theo Baker, the son of New York Times White House correspondent Peter Baker—the paper’s go-to packager of ascribed antisemitic motivations to anti-war protests—and New Yorker politics writer Susan Glasser. In a fitting cross-generational Ouroboros of panicked analysis, Baker fils writes his anguished dispatch from the campus of Stanford, where Packer’s own father worked as an administrator during Stanford’s own convulsions of anti-war protest. His essay is naturally titled “The War at Stanford,” and comes bearing The Atlantic’s version of a Good Housekeeping seal as its subhead: “I didn’t know that college would be a factory of unreason.” You have already read a summary of its argument in the foregoing 2,000 words.

One scours the American media landscape in vain for establishment-sanctioned ruminations on how the litany of free-speech minded grievance is replicating itself on privileged university campuses and in the assortative mating habits of our pundit class. It’s an especially baroque and myopic structure of rationalization for a major publication to erect in the de facto defense of a war that—along with conditions of civilian mass slaughter and famine—has involved the bombardment and destruction of more than 200 schools and universities. But then that’s to be expected: As Donald Trump taught us long ago, it’s always the sober diagnosticians of wilding who are responsible for the real thing.