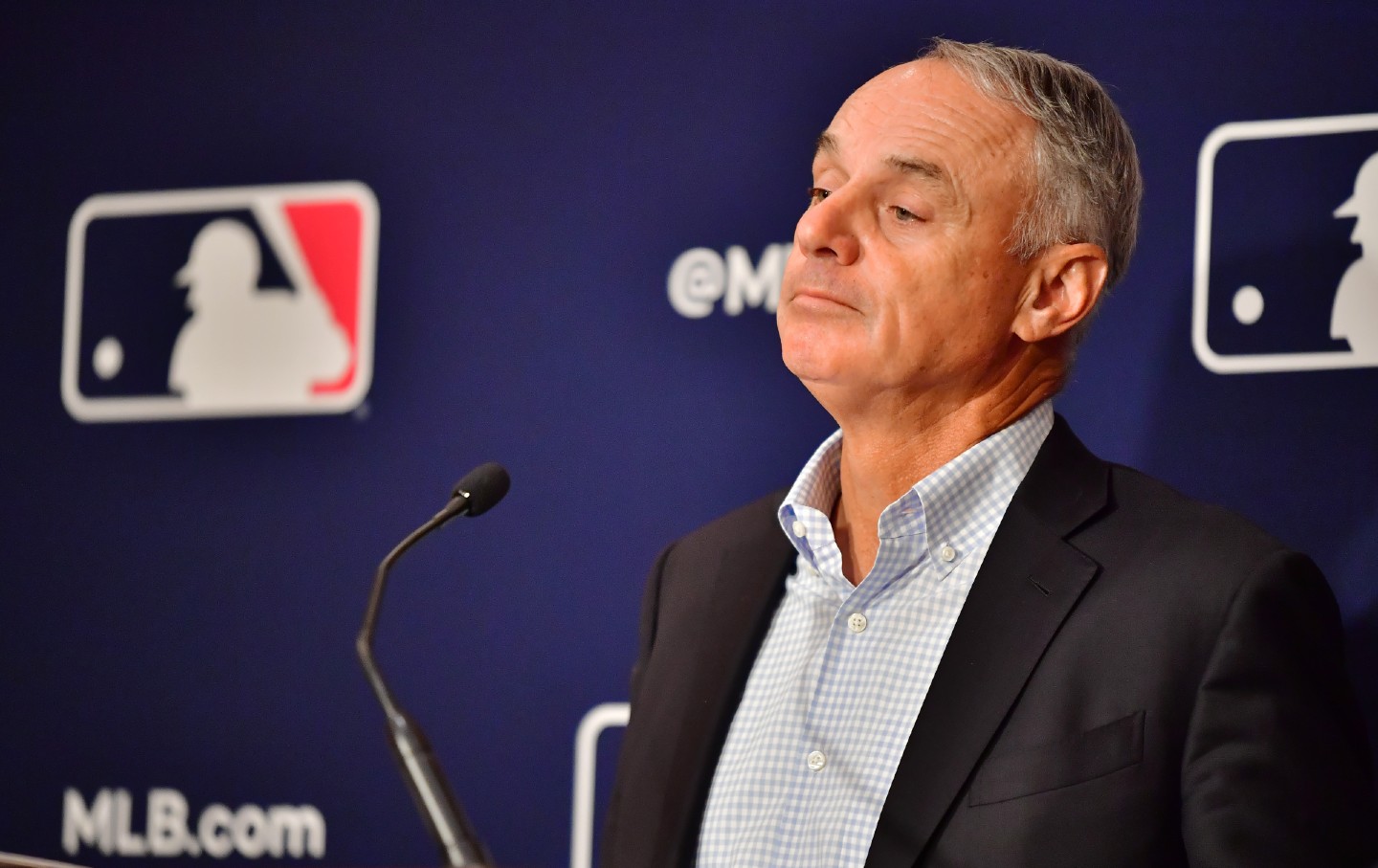

Major League Baseball Commissioner Rob Manfred answers questions during an MLB owner’s meeting at the Waldorf Astoria on February 10, 2022 in Orlando, Fla. Manfred addressed the ongoing lockout of players, which owners put in place after the league’s collective bargaining agreement ended on December 1, 2021. (Photo by Julio Aguilar / Getty Images)

There is joy in Muddville this morning, because the Major League Baseball season is officially back. The 99-day owners’ lockout is over, a new CBA being ratified, and, not only is baseball returning but, despite the second-longest work stoppage in MLB history, no games will be lost. Teams will take the field in time for April 15, the 75th anniversary of Jackie Robinson’s entry into the sport. That all 162 games will be played is a departure from what Rob Manfred, the MLB commissioner, said from the podium earlier this month during what looked like a negotiating standstill. In the minds of players, this will be reason number 1,000 why Manfred is not to be trusted.

But beyond Manfred, a toadstool for billionaires, the question inevitably arises as to who won and who lost in this particular deal. The most prominent winners are stadium workers, who can go to work without missing any games—and fans looking forward to a little baseball escapism amid difficult times. As for the players and the owners—and the battle that traces back into the 19th century, as long as there have been players and owners—assessing winners and losers is more complicated. Any time the billionaires, who voted for this deal unanimously, can feel confident enough to stall negotiations and lock out a union to impose conditions by brute force, that’s not a good sign. That they risked Robinson’s diamond anniversary and a significant part of the season for what they eventually got is disturbing. It shows a contempt for the game and its history.

That’s not the only way this contempt was expressed. There will now be 14 playoff teams, which will create new revenue but further dilute the regular season and chip away at one of the aspects of baseball that make it special: the joy of making the playoffs. There will also now be a designated hitter in the National League, finally eliminating something that’s been part of the game since Alexander Cartwright brought his squad out to Elysian Fields: how you strategize around a pitcher’s underwhelming ability to hit a ball. If those two decisions rankle traditionalist fans, one could imagine the response to something that Manfred once said would be absolutely verboten: the placing of ads on Major League uniforms. This will turn the classy simplicity of Yankee pinstripes or Dodgers blue into a stock car, further miring the game in its cult of commercialism. Some of these revenue streams will be passed on to players’ salaries, as the minimum wage for a player is now up 23 percent and the amount a team can spend on its players before it is hit with a “luxury tax” has also risen. But there is still no salary floor, which many fans had hoped for and would have compelled teams to invest more in talent. It could have transformed a league currently dominated by perennial contenders and where some teams can barely roll out Major League rosters. In addition, forthcoming changes to the rules of the game, like a pitch clock to increase the speed of contests and larger bases, could go into effect by 2023 if approved by a combination of players and management.

The players’ vote, unlike the owners, was split, as Tyler Kepner aptly explained:

The agreement passed by a 26-12 vote of union leadership that broke down this way: 26-4 among the 30 player representatives for each team, and 0-8 among the members of the executive subcommittee. The team representatives speak for the rank-and-file on their rosters. The subcommittee members are much more heavily involved, and also tend to be richer; four of the eight have signed nine-figure contracts, and all have made at least $37 million. The vote was a good reminder that most of the union members are not as rich as you may think; the median salary for M.L.B. players last season was $1.15 million, down from $1.65 million in Manfred’s first year in office.

That last line demands a closer examination: Despite exploding franchise valuations and massive local cable deal contracts, baseball owners have been crying poor while lowering salaries by 33 percent over the past seven years. While the players’ solidarity ensured that they were able to secure gains for marginal and young players, that the games were risked at all speaks volumes.

After the agreement was announced, Senator Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.) said the following, “These are baseball oligarchs who negotiated in bad faith for more than 100 days in a blatant attempt to break the players’ union. These are baseball oligarchs who, over the last year, eliminated their affiliation with over 40 minor league teams, not only causing needless economic pain and suffering, but also breaking the hearts of fans in small and mid-sized towns all over America.”

Obviously, using the word “oligarch” at this moment is not only factually accurate; it is also extremely loaded and could speak to trouble for our homegrown oligarchs down the line. Sanders promised legislation to end baseball’s anti-trust exemption, which allows it to operate above government scrutiny as a legal monopoly. If the lockout ends with the oligarchs under the hot lights, then perhaps it will have been worth it.

Correction: Due to an editing error, a previous version of this article indicated that Jackie Robinson broke baseball’s color barrier nearly 60 years ago. In fact, Robinson debuted for the Brooklyn Dodgers almost 75 years ago.

Dave ZirinDave Zirin is the sports editor at The Nation. He is the author of 11 books on the politics of sports. He is also the coproducer and writer of the new documentary Behind the Shield: The Power and Politics of the NFL.