Billionaires Won’t Save Local News. Here’s What Will.

Praying for beneficent tycoons is not the answer. We need the government to step up.

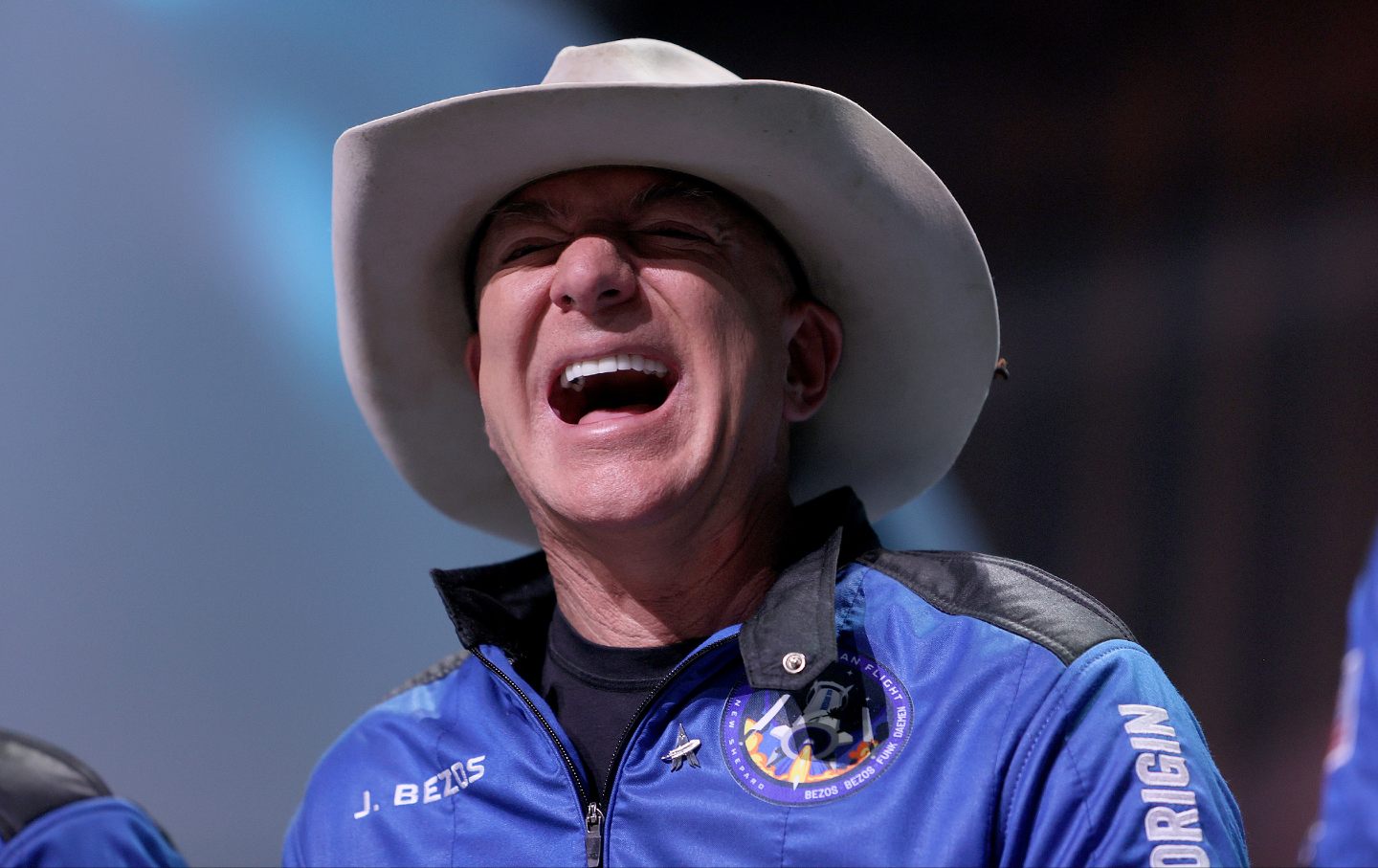

Washington Post owner Jeff Bezos laughs as he speaks about his flight into space on Blue Origin’s New Shepard, during a press conference on July 20, 2021, in Van Horn, Tex.

(Joe Raedle / Getty Images)Local journalism is fading fast. According to Northwestern’s Journalism School’s annual report on the state of journalism, which came out last fall, the United States was losing an average of 2.5 newspapers per week in 2023. That was up from two per week in 2022. Since 2005, the country has lost nearly 2,900 newspapers and two-thirds of its newspaper journalists, or 43,000 people.

The bad news keeps coming. In late January, the widely respected Baltimore Sun was taken over by a billionaire executive from the right-wing Sinclair news network. He quickly told the staff that their job was to get clicks. That same week, the Los Angeles Times announced a new round of layoffs.

This should be very troubling for people who care about democracy. The news media plays an enormously important role in informing the public and exposing corruption. The loss of local news outlets essentially gives free rein to corrupt local politicians and businesses.

The old business model that supported newspapers throughout the last century is no longer viable. Before the Internet age, newspapers relied primarily on advertising revenue to support their operations, with subscription revenue roughly covering the cost of printing and distributing the paper.

The Internet destroyed this model from both ends. First, the vast majority of readers want their news online rather than in print. This mattered because online advertising generally generates less revenue than print does. Department stores were more willing to pay to have people staring at their ads as they looked through different articles on a printed page than to have them quickly glancing at the ads as they clicked around a website.

On the other side, the Internet opened up a vast array of alternative advertising possibilities. That is true not just for major retailers but also for people who want to sell a car or a piece of furniture or advertise a job opening. Classified ads used to provide a healthy stream of revenue for newspapers, but they are now pretty much dead. It also doesn’t help that Google and Facebook manage to scoop up a disproportionate share of the relatively meager online ad revenue that is available.

With the old model no longer working, the newspaper industry is collapsing. This has provoked considerable hand-wringing, but not many proposed solutions. For the past decade or so, the go-to answer has appeared to be “find a beneficent billionaire.”

Beneficent billionaires are great (until they turn the money taps off, as has happened at the Los Angeles Times and Jeff Bezos’s Washington Post), but that is not a serious way to support an essential public service like local newspapers. We need a new model.

Fortunately, there is an alternative: investing public dollars into journalism. The idea of public subsidies for news outlets is hardly new.

As Robert McChesney and The Nation’s John Nichols note in their “Local Journalism Initiative” proposal, the government used to heavily subsidize newspapers by requiring the postal service to distribute them at below cost. They calculate that this subsidy came to 0.21 percent of GDP, which would be almost $60 billion a year in today’s economy. Many public notices are also required to appear as paid ads in newspapers. And government-granted copyright monopolies are an explicit subsidy to newspapers, and creative work more generally, laid out directly in the Constitution.

The key issue is to have the subsidy distributed in a way that protects the content from government interference. This can be done through a system where the government gives people a coupon or tax credit so that they can support the news outlet of their choice.

The model for this sort of system is the charitable contribution tax deduction. The IRS grants organizations tax-exempt status based on what they do, not whether it likes what they do. This means that a church, a college, or a homeless shelter all qualify for tax-exempt status based on being a church, college, or homeless shelter.

The IRS does not try to determine whether the church, college, or shelter is “good”; that is for potential contributors to assess. To get tax-exempt status, the IRS just determines whether these organizations engage in the activity they claim.

There would be a similar determination in assessing eligibility for local journalism tax credits. A news outlet would merely have to show that it was engaged in the process of reporting local news. There would be no effort to determine whether it was doing a good job in reporting local news—that would be up to the individuals using their tax credits.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →The news outlets getting the credit would also have to make their material freely available to the public outside of paywalls. This one is simple. Since the public is paying for the work, it gets to benefit from it.

The other big difference between the charitable deduction and this tax credit system is that beneficiaries of the tax deduction are almost exclusively high-income households. Almost 90 percent of the population takes the standard deduction, which means they are not eligible for the charitable contribution tax deduction.

The local journalism tax credit would be a fixed amount, say $100, for everyone. It is fully refundable, so everyone gets it. This sort of system could easily make up for the collapse of advertising revenue over the last three decades.

The death of journalism is a national problem. Ideally, we would have a tax credit available to everyone in the country. However, given the current state of Congress, expecting national legislation along these lines would be as unrealistic as relying on beneficent billionaires. But this sort of local journalism tax credit can be put in place at the state or even local level.

Currently, there are efforts in both Seattle and Washington, D.C., to establish a system of local news tax credits. There are many details to work out, and there will be serious political obstacles to overcome even in these relatively liberal cities.

However, the point is that we can devise mechanisms to support local journalism. We have long recognized the need to support this essential public service with subsidies, but these are no longer sufficient to keep the industry alive. We need a new mechanism—because praying for beneficent billionaires won’t do the trick.

Hold the powerful to account by supporting The Nation

The chaos and cruelty of the Trump administration reaches new lows each week.

Trump’s catastrophic “Liberation Day” has wreaked havoc on the world economy and set up yet another constitutional crisis at home. Plainclothes officers continue to abduct university students off the streets. So-called “enemy aliens” are flown abroad to a mega prison against the orders of the courts. And Signalgate promises to be the first of many incompetence scandals that expose the brutal violence at the core of the American empire.

At a time when elite universities, powerful law firms, and influential media outlets are capitulating to Trump’s intimidation, The Nation is more determined than ever before to hold the powerful to account.

In just the last month, we’ve published reporting on how Trump outsources his mass deportation agenda to other countries, exposed the administration’s appeal to obscure laws to carry out its repressive agenda, and amplified the voices of brave student activists targeted by universities.

We also continue to tell the stories of those who fight back against Trump and Musk, whether on the streets in growing protest movements, in town halls across the country, or in critical state elections—like Wisconsin’s recent state Supreme Court race—that provide a model for resisting Trumpism and prove that Musk can’t buy our democracy.

This is the journalism that matters in 2025. But we can’t do this without you. As a reader-supported publication, we rely on the support of generous donors. Please, help make our essential independent journalism possible with a donation today.

In solidarity,

The Editors

The Nation