One Big Cookout: From the “Negro Press” to Black Twitter

We always suspected that whatever magazines and newspapers for white folks weren’t telling us, Black newspapers and magazines would.

My father’s family tree has a Capt. Charles L. Mitchell, born in my hometown of Hartford, Conn., who took what he learned during what was later described as a “relatively brief tenure at that city’s venerable Courant” to establish a Black-oriented newspaper, also called the Courant, in his adopted city of Boston in the late 19th century. On my mother’s side of the family, there was, most notably, my uncle C. Sumner “Chuck” Stone Jr., who was at various times in the 1950s and ’60s editor of The New York Age, The Washington Afro-American, and The Chicago Defender—all before his 18-year run as a columnist, political gadfly, go-between for law enforcement and Black suspects, and senior editor at the Philadelphia Daily News. Scrolling recently through old copies of the Age, which closed in 1960 after 73 years, I was astonished to find that Chuck’s sister (and my mother) Madalene contributed a column covering Hartford’s Black social calendar. I suppose, despite the roughly 110 miles separating them, Hartford and Harlem were still close enough to require the kind of society updates that Black newspapers were renowned for providing. But as both Chuck and Mom are gone now, I doubt I’ll ever get the whole story.

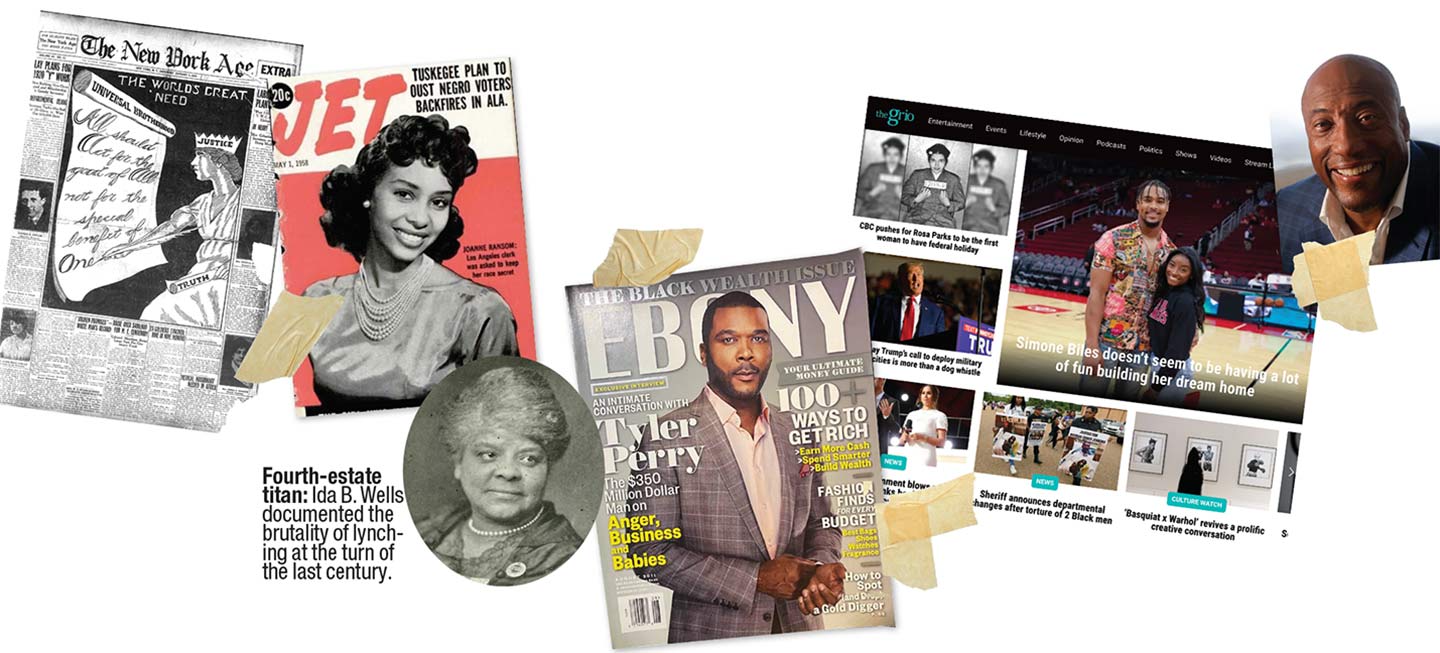

The more pertinent point is that, although it wasn’t exactly the family business, journalism was viewed in my Black household, as in others, as crucial to our collective advancement and identity. In the racial tumult and upheaval of the 1960s, our devoted consumption of Black news outlets—not just newspapers, but also magazines such as Ebony, Jet, and the lesser-known but still fondly remembered Sepia—was vital because we always suspected that whatever magazines and newspapers for white folks weren’t telling us, Black newspapers and magazines would.

Ebony is still around, as are Black-owned-and-operated news outlets following the centuries-old mandate of making Black people feel less invisible and more connected to one another. But the once-mighty flagship of Johnson Publishing has had to retool and rebrand itself for a digital age that has all but forgotten what it was like to have living-room end tables bulging with glossy journals and newsprint. What was once known and cherished as the “Negro press” has become “Black media,” which in its larger, more sprawling manifestation still tries to reflect what the Black diaspora is thinking and talking about.

Better still to imagine Black media as One Big Cookout—“cookout” being the go-to metaphor for African American consensus. The analogy may be unwieldy, given the many contemporary variants and offshoots of Black media. It fits nicely, however, when you’re talking about Black Twitter. Want to know how the latest revelation concerning the fraught marriage of Will and Jada Pinkett Smith registers with the Black boomers, Gen-Xers, and millennials who once avidly watched The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air? Consult Black Twitter. How’s the newly styled hair of basketball star Jimmy Butler going over? Black Twitter will be happy to let you know. Was another unarmed Black person killed by police or assaulted by white bigots? Black Twitter gives you a seismic reading on the level of outrage.

But as with Twitter—or X, or whatever Elon Musk calls it these days—Black Twitter reacts (and then riffs on those reactions) far more often than it reports what it’s reacting to. Black Twitter will not be the first to tell you, for instance, what the unemployment rate is among Black Americans (currently 5.8 percent) or what that means for parents, children, and their respective needs. Nor will it be the first—or maybe even the second—to tell you what elected officials plan to do about affordable housing, student loan debt, union organizing, or effective neighborhood policing, or whether charter schools are really a better option for your kids than public education. And Twitter, Black or white, isn’t going to tell you the impact that changing the street where you live from two-way to one-way will have on your walk to the grocery store two blocks away.

And as to how all these issues might directly affect African Americans, the mainstream (read “white”) press will hardly ever go long or deep. Which is why the metaphorical cookout that is Black media today encompasses everything from the more than 200 Black-owned-and-operated newspapers that make up the National Newspaper Publishers Association (NNPA) to online platforms like The Root, the digital reincarnations of Ebony and Jet, and TheGrio, whose website, with its formidable array of news, opinion, features, investigative stories, and political commentary, is a key component of a multi-platform media network owned by Byron Allen, the stand-up comedian turned media mogul. TheGrio’s own Twitter page proclaims itself as simply “Black Culture Amplified.”

Media Special Issue

“We cover social justice, entertainment, lifestyle,” says Geraldine Moriba, an award-winning documentary producer and filmmaker who is now TheGrio’s senior vice president. “Whatever the Black community is talking about today or should be talking about today, we’re trying to cover it.”

Allen, whose ever-expanding conglomerate comprises television stations and programming, podcasts, and live sports, sees Black media as a means of economic empowerment for the Black community—and a vehicle for broadening America’s vision of itself.

“You have to have a seat at the table,” Allen says. “You have to control your image and your likeness and how you’re depicted around the world…. Media is so powerful—it can be weaponized to the point where you had people on January 6 so wound up and angry, they’re trying to overthrow a country that they already control.” But, he adds, “media can be used to unite us. Media can be used to introduce ourselves to each other.”

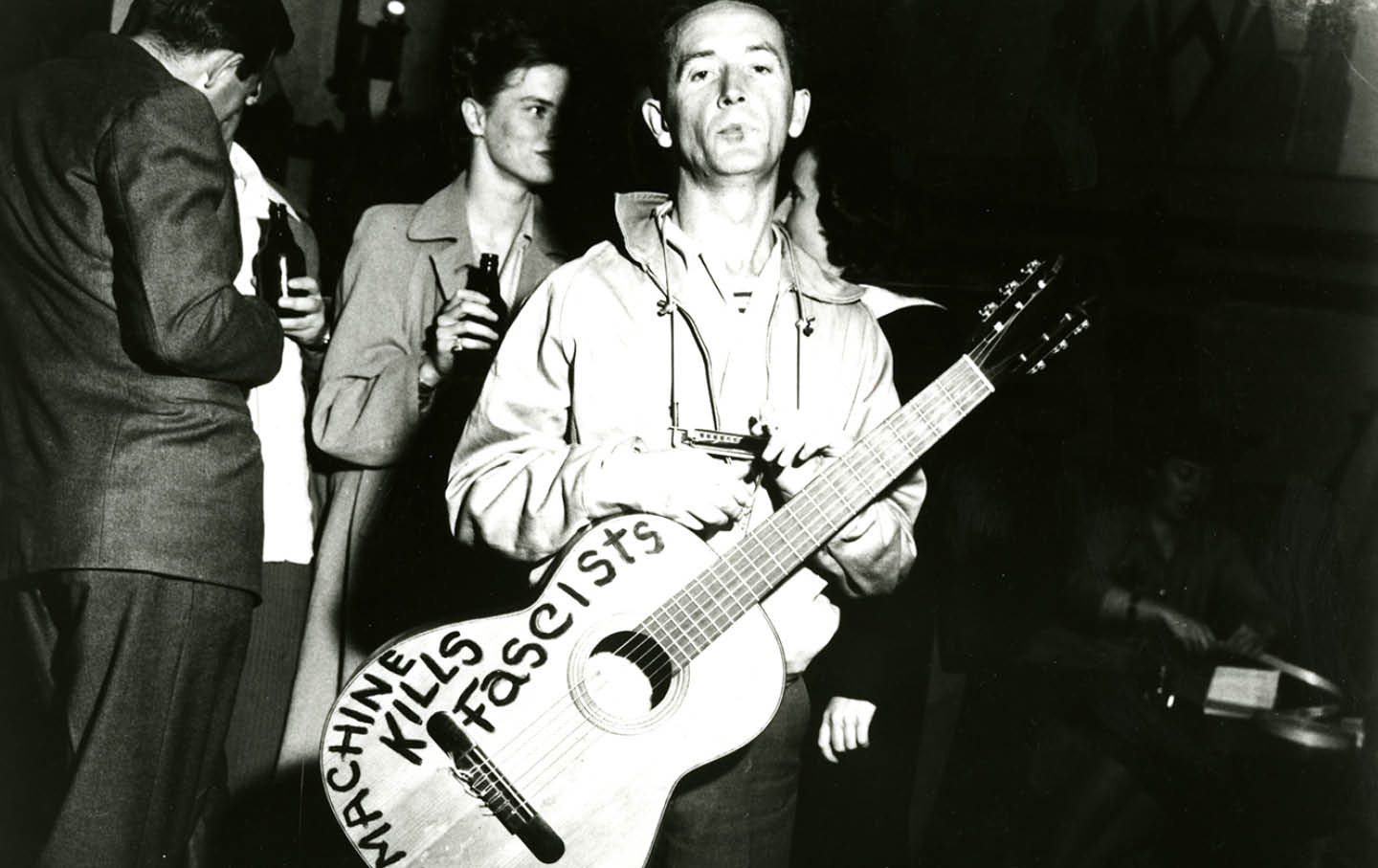

Allen’s vision eagerly broadens and steadfastly reinforces the centuries-old mission of the Negro press, which, from its beginnings in 1827—when John Russwurm and Samuel Cornish founded Freedom’s Journal—sought to make visible people whose dimensions, possibilities, and achievements were made imperceptible even to themselves. The fusion of ink, newsprint, and eventually photographs bore magical, transformative properties for Black America through the brave work of word ninjas like Frederick Douglass, Ida B. Wells, William Monroe Trotter, and Walter White, who stalked and often subdued superstition, injustice, and legally sanctioned barbarism against people of color.

In the bad old days of Jim Crow, Black-owned newspapers like The New York Age, Chicago Defender, Pittsburgh Courier, and Baltimore Afro-American exposed lynching, helped facilitate the Great Migration of Blacks from the rural South to the urban North, exposed discriminatory practices in housing, employment, and courtrooms, and reinforced African Americans’ collective identity and self-worth.

Such impulses still drive Black media—even as NNPA-member news outlets have had to make the same adjustments to digital demands that mainstream publications have. “A lot of us have become revived because of digital transformation,” says Denise Rolark Barnes, the publisher of The Washington Informer, a family-owned newspaper that has served the D.C. Black community for 59 years. “It has taken a while not just to get on that train, but to even find a seat. There’s something about what we do and have done historically that I think has saved our publication and those like it. The question is: How do we generate enough revenue to continue to not just survive but thrive?”

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →Barnes’s publication and others like it also have to compete in a media market that is at once broader and narrower in scope than it was in the mid- to late 20th century. Among the findings in a September Pew Research Center report on Black Americans’ relationship with the news is that about a quarter of the African American adults surveyed—24 percent—say they get news from Black media outlets, while a third say they get news from a mélange of sources, including local and national outlets, social media sites, friends, and family acquaintances. This rough profile seems aligned with how most Americans piece together their regular news diet.

The Pew report also notes, however, that nearly 63 percent of those polled believe news coverage of Black people is more negative than news about other racial and ethnic groups. And at least half the people surveyed say the news they see and hear about Black people is limited to “certain segments” of their communities and misses important information that could bring balance and perspective to their stories. Which sounds a lot like the same complaints that cemented Black readers’ age-old loyalty to Black-owned-and-operated news outlets.

Those perceptions may not be as deeply embedded as they once were. But Geraldine Moriba, who worked for CNN, PBS, NBC, and other television networks before moving to digital media, says there is still a need for Black outlets such as TheGrio to convey the full and diverse voice of her community.

“My biggest challenge was the daily editorial call at places like CNN,” Moriba says. “Most of the time, I was the only one at the meeting pitching stories about people of color, defending the value of those stories, sometimes even explaining why they’re stories. Even though I knew my own experience was unique, I was still trying to explain the experiences of other Black people in a way that would get them picked up [by the network]. Now that I’m senior vice president at TheGrio, I look forward to those daily calls, because I know we’re not going to end up defending the value of those stories or whether we should be reporting them. We’re going to debate the angles, discuss the layers in a story, and then decide the ‘how’ more than the ‘whether.’”

Still, the Pew report suggests that Black consumers’ expectations about who should cover such stories are changing: While 45 percent of the respondents say Black journalists do a better job covering issues related to race and inequality, only 14 percent said it is important that any news they get, regardless of topic, comes from Black journalists.

Gauging who turns up at the cookout, in other words, is trickier than it seems. As is figuring out where Black-owned outlets fit into the era of electronic media.

“The newspaper has gone away,” Allen says. “But that has more to do with technology, not behavior. No one woke up and said, ‘I don’t want news from my community.’ They woke up and said, ‘I want it from a digital platform.’ Our digital platforms, our local TV stations, are growing in terms of engagement and revenue, which means the platforms are the new newspaper. They may not want the paper, but they want the news. And the Black press is needed more than ever, and it has more power than ever before, because the Black press now, for the first time, has global distribution through technology.”

But Richard Prince, a veteran African American journalist who since 2002 has run Journal-isms, a website that monitors diversity issues in the news industry, says much of Black media is struggling to keep up with the demand for faster, better news coverage of their communities.

“Historically, Black news outlets have talked about emphasizing positive images on their pages,” Prince says. “It goes back to this idea that we shouldn’t put all this bad stuff out there, because mainstream papers are always emphasizing things in our community like crime, guns, and unemployment. But your main task isn’t to be positive. Your task is to deliver the news. And there are ways to engage these so-called ‘negative’ issues in a positive, proactive way that lets your readers, the community, know you’re serving their interests.”

Denise Barnes remembers her father, Calvin Rolark, the founding publisher of The Washington Informer, insisting to her that the paper publish positive news. “I’ve thought about it,” she says. “And I say to myself, ‘We’re a weekly newspaper, and especially in a time like today, if we were to put out on the front page of our paper on Thursday that someone was killed, or five people were shot, people are going to want to know by next Thursday, ‘Well, which people were shot, and who was the killer?’ Well, we can’t keep up with that news. But what we can keep up with is the work the community is doing to engage the problem of violence in our neighborhoods, which is the kind of thing that doesn’t get reported [in mainstream papers]. We’ve talked about and covered marches and demonstrations against police violence in our community years before George Floyd. That may not be a ‘positive’ story per se, but it is a reflection of our community actively seeking solutions to the problems that lead to violence. Which makes the story ‘positive,’ but it doesn’t ignore the ‘negative’ that exists, because we live it.”

As another example of this impulse, Prince cited “Beyond the Barrel of the Gun,” an ongoing series of articles in the New York Amsterdam News investigating the root causes of gun violence in communities of color. Backed by the Google News Initiative Equity Fund, the series exemplifies what Prince characterizes as a “bright spot” of foundation grants made available to Black news outlets.

“Everybody knows there are news deserts everywhere, not just in the Black community,” Prince says. “But the problem for me isn’t that [Black outlets] don’t have the money to do this work. The problem is that, overall, the standards for the Black press aren’t the same as they are in the mainstream press. For instance, when a Black newspaper reported that Tyler Perry had bought BET, it was portrayed as a done deal. And then it turned out it wasn’t a done deal and they embarrassed themselves. You’ve got to have editors around to flag these things down.”

Linn Washington Jr., who served as executive editor of the historically Black Philadelphia Tribune between 1993 and 1995 and still works as a correspondent there, has found other frustrations in trying to do the basics of community news gathering.

“It’s a fact that we in the community don’t always respect our media,” Washington says. “I’ve found Black people who’ll believe the Inquirer [Philadelphia’s major news outlet] before they’d believe the Tribune.”

Despite such frustrations—and the failure of mainstream networks like MSNBC to routinely include representatives from Black media on their programs—Washington values papers like the Tribune that manage to survive despite the obstacles. Barnes, whose Informer has nine full-time employees and 11 freelancers, likewise believes there will always be a place for Black news outlets.

“It’s a matter of trust,” she says. “It’s like being home. Sometimes we don’t always value home, but it’s that place where the people who are writing about us, photographing us, editorializing about our issues—they know us. Because they are us.”

Hold the powerful to account by supporting The Nation

The chaos and cruelty of the Trump administration reaches new lows each week.

Trump’s catastrophic “Liberation Day” has wreaked havoc on the world economy and set up yet another constitutional crisis at home. Plainclothes officers continue to abduct university students off the streets. So-called “enemy aliens” are flown abroad to a mega prison against the orders of the courts. And Signalgate promises to be the first of many incompetence scandals that expose the brutal violence at the core of the American empire.

At a time when elite universities, powerful law firms, and influential media outlets are capitulating to Trump’s intimidation, The Nation is more determined than ever before to hold the powerful to account.

In just the last month, we’ve published reporting on how Trump outsources his mass deportation agenda to other countries, exposed the administration’s appeal to obscure laws to carry out its repressive agenda, and amplified the voices of brave student activists targeted by universities.

We also continue to tell the stories of those who fight back against Trump and Musk, whether on the streets in growing protest movements, in town halls across the country, or in critical state elections—like Wisconsin’s recent state Supreme Court race—that provide a model for resisting Trumpism and prove that Musk can’t buy our democracy.

This is the journalism that matters in 2025. But we can’t do this without you. As a reader-supported publication, we rely on the support of generous donors. Please, help make our essential independent journalism possible with a donation today.

In solidarity,

The Editors

The Nation