Their Atrocities—and Ours: Thinking About the Wrong Side of History

Can a cause still be just, even if atrocities have been committed on its behalf?

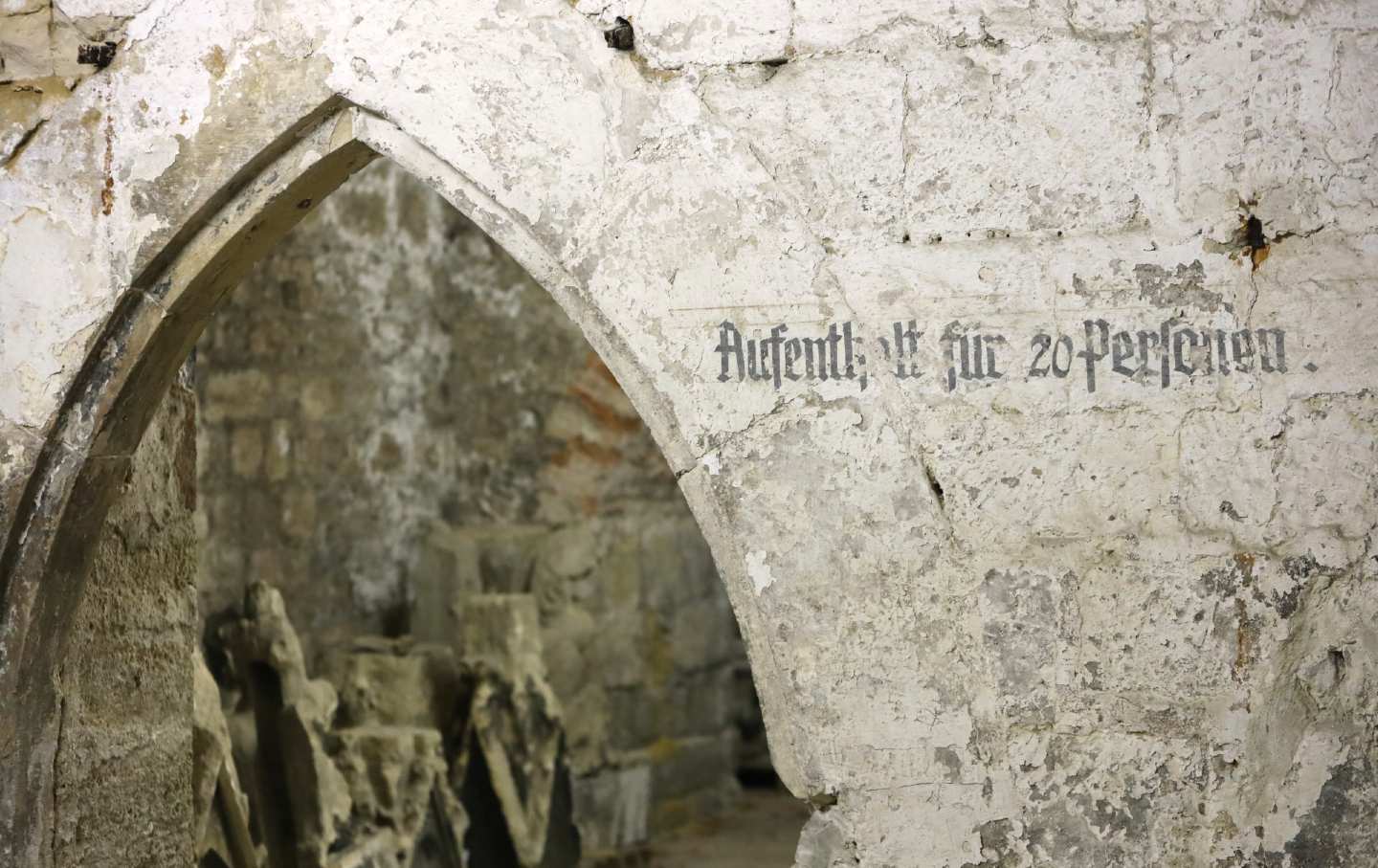

There is a set of images to which Americans do not have much access. It consists of photos of German cities after the American bombing raids of World War II: photos of Germans pulling the bodies of children out of their bombed-out homes, stacking corpses on carts, sifting through the rubble for what might remain of their possessions. Why are these images missing from the collective memory? Is it because the United States had no photojournalists in enemy territory? Or are they unremembered because, unlike so many of the bombing campaigns that followed, this one belonged to what we think of as a good war? Most US readers probably have little desire to contemplate the collateral damage, measured in German civilian lives, of a victory over fascism that everyone agrees was noble and necessary.

These images do exist, of course, and I have often thought of them over the past months thanks to the images from Gaza, which they resemble. But they first came to my mind long before October 2023. One afternoon a few years ago, I was sitting on the sofa reading The Air Raid on Halberstadt on 8 April 1945, a book of text and images in which the German philosopher Alexander Kluge documents the arrival of the US Eighth Air Force over his hometown. As I was reading, something about the title struck me as mysteriously familiar. I went into my study. Framed on the wall was a scrap of paper listing the missions my father flew as a bomber pilot during the waning months of the war. And there it was, in his own handwriting: “Halberstadt. 8 April 1945.” While the 13-year-old Alexander Kluge waited to see whether he would die, as two or three thousand of his neighbors did in the explosions and fires around him, my father, Capt. Eugene Rabinowitz, age 21, was steadying his B-17 over Halberstadt, the bomb bay doors open.

Some months after I looked at my dad’s flight record, I managed to meet Alexander Kluge. He was very kind. Kluge did not say anything about how it felt as a child to be bombed. He told me that the men in those planes had no more control over where they dropped their bombs than workers in a factory have over what their factory produces. Then he mentioned some seemingly random episodes of violence, among them the eradication of the Neanderthals and a 18th-century pogrom against Jews in Prague. This was confusing. I decided afterward that the far-flung examples of atrocity he mentioned helped relativize, for him, the awfulness he had lived through as well as American accountability for it.

Face to face with an atrocity, historical relativizing doesn’t seem like the obvious move. Mass violence against noncombatants—my rough definition of “atrocity”—can hardly appear, looked at up close, as anything but unbearable, incomprehensible, inhuman. The only thing to feel about it is indignation. The only way to judge it is to say that the perpetrators must be monsters. Whatever side I am on, it can’t be theirs. Whatever is done to their side by way of retaliation, they are the ones responsible for it.

That is what many people decided after the Hamas attacks of October 7, 2023. But that line of reasoning is a mistake—as I think Kluge was trying to tell me. What was done in Halberstadt was monstrous, but my father was not a monster. Human history is full of violence, and you can’t understand that history, or play any role, even the slightest, in preventing future atrocities, if innocent victims and guilty perpetrators are all you see in it.

A cause can still be just even if atrocities are committed on its behalf. That was the case with the Allied bombing of German cities. It is not the case in Gaza, even if the Israeli pilots who have been doing the bombing deserve some share of the complicated mixture of sympathy and abhorrence that cohabits in me with my love for my father. (Who knows what their officers have told them?) Palestinians, on the other hand, have every right to struggle for self-determination and an end to occupation and blockade—even if the violence committed by Hamas on their behalf is unforgivable. The Native Americans who murdered women and children while defending themselves against encroaching settlers during King Philip’s War in 1676 were not wrong to defend their homes, even if we do not approve of the atrocities that accompanied that defense. The situation was not symmetrical. The Native Americans had not paddled their canoes up to England’s shores, burned English homes, taken over English woodlands.

But if atrocity does not make a cause unjust, it does not follow that the existence of atrocities can be ignored. To commit an atrocity is still the single worst thing anyone can do. It stops you in your tracks—and so it should. Yet that doesn’t rule out attention to differences in quantity, proportion, and circumstances. Like the supporters of Israel who harp on October 7, the German historians who draw a moral equivalence between the Allied bombing of German cities and the Holocaust—as if the sufferings brought by the former canceled out German guilt for the latter—are neglecting important distinctions. My father told me his targets were only military and industrial. This statement turned out to sometimes be true, though it was not true of the raid on Halberstadt. At Auschwitz, there was no intention to avoid civilian casualties.

Listening to the implausible verbiage with which Israel defends its daily carnage in Gaza, it will seem naïve or worse to demand acknowledgment for the history of good intentions that has produced the modern concept of atrocity—intentions so often ignored in practice. But that history helps distinguish between Gaza now and Halberstadt then.

Because the killing of noncombatants was not always considered shameful. Once upon a time, when plunder was a principle of economic survival, conquest was a matter of pride. Before the rise of modern international law, conquest was understood to confer rights of sovereignty. If you conquered a territory, it was yours to rule. Not only did conquest not violate any legal or moral norm; it was celebrated. What do you do with conquering heroes if not hail them? And the same was true of the atrocities that conquest necessarily brought in its wake. Armies lived off the land, which meant taking what they needed from those who lived on the land. Soldiers were routinely promised, and rewarded with, booty. Under these circumstances, it was inconceivable that any moral norm should arise condemning the mass killing of noncombatants. The word atrocity signified excessive cruelty; it did not refer to the identity of the victims. The modern concept of atrocity as a victim-based moral scandal could not exist then. Yet now it does.

Our leaders no longer brag about the number of people killed, as Julius Caesar did when he conquered Gaul. The passage of time has done more than add to the chronicle of excruciating acts of violence; it has also changed how those acts are and should be judged. Since the raid on Halberstadt, human rights and humanitarian law have sharpened the world’s moral consciousness. Our leaders may cynically prefer the word atrocity to genocide, since the latter comes with the imperative to do something. Still, they have reason to know better now than they did, even in World War II, that history will not applaud their success in wreaking mass violence on defenseless noncombatants. The IDF and its American enablers are guiltier than the Eighth Air Force because the nearly 80 years that have gone by have not been morally meaningless. For the same reason, the rest of us have more responsibility to hold the IDF and its American enablers accountable.

The phrase “the right side of history” sounds lame these days; few would admit to sharing Martin Luther King Jr.’s conviction that the arc of the moral universe, though long, bends toward justice. The great pain that comes with attending to atrocities past and present tests such little faith as may persist. Still, there is obviously a wrong side of history. Anyone seeking its right side can begin by calling for an immediate end to the bombing.

Disobey authoritarians, support The Nation

Over the past year you’ve read Nation writers like Elie Mystal, Kaveh Akbar, John Nichols, Joan Walsh, Bryce Covert, Dave Zirin, Jeet Heer, Michael T. Klare, Katha Pollitt, Amy Littlefield, Gregg Gonsalves, and Sasha Abramsky take on the Trump family’s corruption, set the record straight about Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s catastrophic Make America Healthy Again movement, survey the fallout and human cost of the DOGE wrecking ball, anticipate the Supreme Court’s dangerous antidemocratic rulings, and amplify successful tactics of resistance on the streets and in Congress.

We publish these stories because when members of our communities are being abducted, household debt is climbing, and AI data centers are causing water and electricity shortages, we have a duty as journalists to do all we can to inform the public.

In 2026, our aim is to do more than ever before—but we need your support to make that happen.

Through December 31, a generous donor will match all donations up to $75,000. That means that your contribution will be doubled, dollar for dollar. If we hit the full match, we’ll be starting 2026 with $150,000 to invest in the stories that impact real people’s lives—the kinds of stories that billionaire-owned, corporate-backed outlets aren’t covering.

With your support, our team will publish major stories that the president and his allies won’t want you to read. We’ll cover the emerging military-tech industrial complex and matters of war, peace, and surveillance, as well as the affordability crisis, hunger, housing, healthcare, the environment, attacks on reproductive rights, and much more. At the same time, we’ll imagine alternatives to Trumpian rule and uplift efforts to create a better world, here and now.

While your gift has twice the impact, I’m asking you to support The Nation with a donation today. You’ll empower the journalists, editors, and fact-checkers best equipped to hold this authoritarian administration to account.

I hope you won’t miss this moment—donate to The Nation today.

Onward,

Katrina vanden Heuvel

Editor and publisher, The Nation