To Build Working-Class Power, We Need a Workers’ Education Movement

A century ago, labor colleges transformed American unions. It’s time to bring them back.

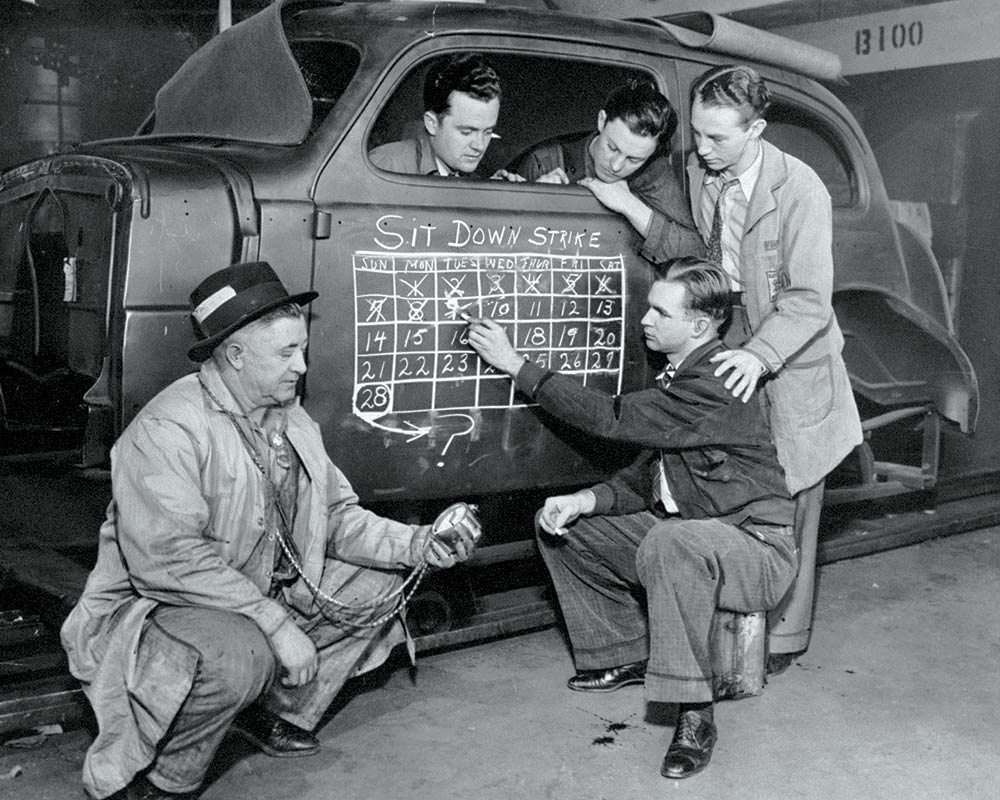

In December of 1936, a day into their historic sit-down strike at a General Motors plant in Flint, Michigan, autoworkers set up a school. Surrounded by idle machines, freed from the foreman’s gaze, they took classes in public speaking and labor journalism, in political economy, in the history of the labor movement.

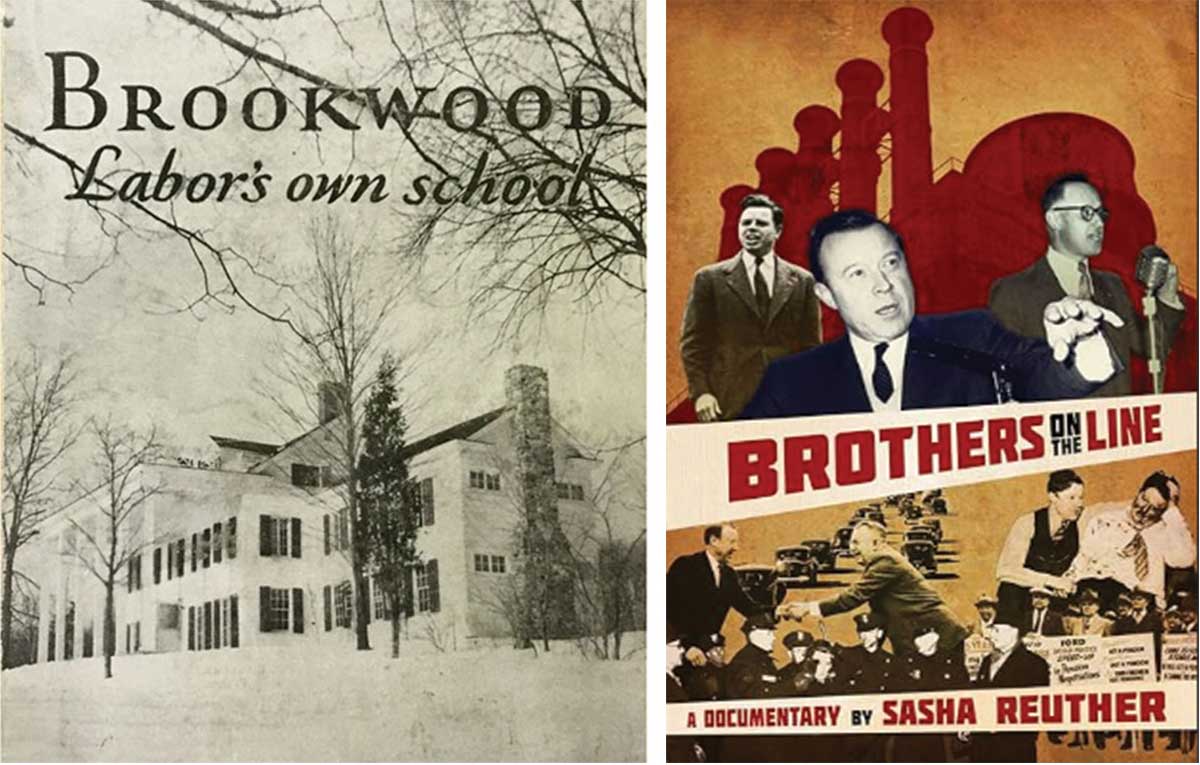

This was not a spontaneous idea. Some of the key players in the strikes—the education director and several rank-and-file organizers in the nascent United Auto Workers (UAW), as well as its future president, Walter Reuther, and his brother, Roy—had spent time at Brookwood Labor College, a small independent school for workers who wanted to radicalize the labor movement. Many of the classes at the factory in Flint were based on those at Brookwood. In a way, so was the strike itself. It was at Brookwood that the Reuther brothers first studied the sit-down—a tactic that would be deployed in the coming year by nearly 400,000 workers in one of the most radical upsurges in American labor history. The start of the modern labor movement in America owed a lot, as one historian puts it, to “Brookwood’s Detroit vanguard.”

That moment should be front of mind today for a new generation of labor leftists. A rejuvenated UAW invoked the sit-down strikes as a precedent for its successful “stand-up” strike against the Big Three automakers last fall. Today’s young activists are returning to 1930s organizing pamphlets for strategy and inspiration. There are even two new podcasts devoted exclusively to the history of the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO), which was founded in 1935. These retellings and invocations are happy signs of a renascent labor movement. Propelled by enthusiastic young workers and new leaders, unions are starting to organize—and, thrillingly, to strike!

We shouldn’t exaggerate. Union density remains low (10 percent of the overall workforce and just 6 percent of private employees belong to unions), and some of the new wave of organizing has already crashed against capital’s willingness to flout our impotent labor laws. But the excitement is real, and it is prompting labor leaders, activists, and scholars to return to the 1930s for lessons.

So it matters that Brookwood—and, more critically, the vast movement of workers’ education of which the college was but one part—remains largely absent from our narration of labor history. This historical omission is indicative of a contemporary problem: The project of workers’ education is absent from our understanding of labor’s past because it has no role in labor’s present. “There is little clarity about the significance or substance of workers’ education within the labor movement,” wrote Bob Master, a former leader with the Communication Workers of America (CWA) who directed the union’s political education programs in New York, in an unpublished essay from 2017. In fact, he went on, many unions “have abandoned worker education entirely.”

There are exceptions. CWA itself has for many decades run excellent, member-led workshops on finance capitalism, labor history, and current political issues. Some university programs—CUNY’s School of Labor and Urban Studies, for instance—partner with unions to offer accredited courses. A “New Brookwood,” founded in 2019 in St. Paul, runs online night classes. In Arizona, I help coordinate the Worker Power Leadership School, a month-long in-residence program for union members inspired by the 1920s labor colleges.

But such initiatives are few and far between, for reasons both historical and structural. In union-led political campaigns and workplace organizing drives, it is very difficult to create the space for workers to think beyond the demands of the moment. The tendency in even the most militant unions is to focus instead on “organizing trainings”: how to talk to your coworkers, build a committee, tell your story, win the next contract. This is important work, and, done well, it can be a powerful exercise in self-actualization and solidarity. But the ultimate end—the vision of what we are organizing for—is usually simply assumed. Or handed down by union staffers. But political consciousness does not spring organically from being a member of a union, or even from going on strike. For that we need a vast, ambitious, forthrightly ideological program of education that remains grounded in the labor movement without being constrained by its immediate battles.

Brookwood was founded in 1921 in Katonah, New York, by a small group of labor radicals—“socialists with a small ‘s,’” recalled A.J. Muste, the pastor turned labor activist who directed the school for the next 12 years. It was hardly an auspicious moment. The first Red Scare and government crackdowns on leftists during World War I had crippled radical unions and rolled back the gains achieved by mainstream labor during the war. The American Federation of Labor (AFL) remained wary of political action and unwilling to press beyond its base of skilled craft workers. National union density hovered at around 10 percent. And yet it was in this hostile context that left-wing labor activists set up dozens of “colleges” and “institutes.” Their politics varied, but together they constituted an attempt to rejuvenate the labor movement from the ground up in an era of mass politics. Brookwood, its directors declared in a letter to The New York Times, “frankly aims not to educate workers out of their class.”

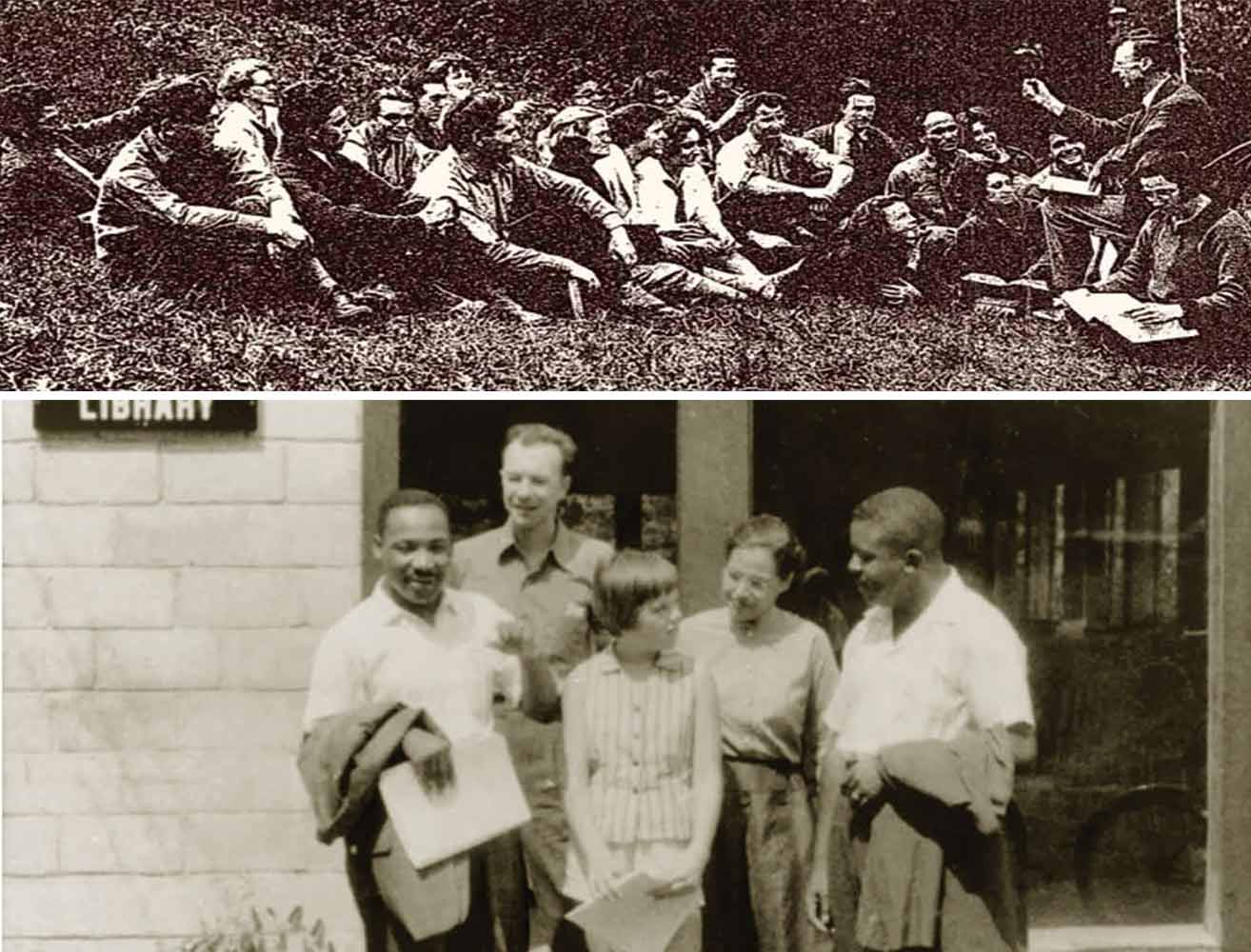

Students were union members who wanted to be active in the labor movement. Educational background did not matter. Of Brookwood’s 42 students in 1927, for example, only 15 had attended high school. The faculty was made up of academic experts who were also engaged in labor politics; many later held leadership positions in unions or the Franklin Roosevelt administration. Everyone lived on “campus”—a cavernous old mansion donated by two rich progressives—and everyone was expected to help with manual labor (though in practice, it was often the wives of faculty members who cooked and cleaned). “Spiritually,” remembered Len DeCaux, a merchant seaman who attended Brookwood from 1922 to 1924 and later served as publicity director for the CIO, “Brookwood was a labor movement in microcosm—without bureaucrats or racketeers.”

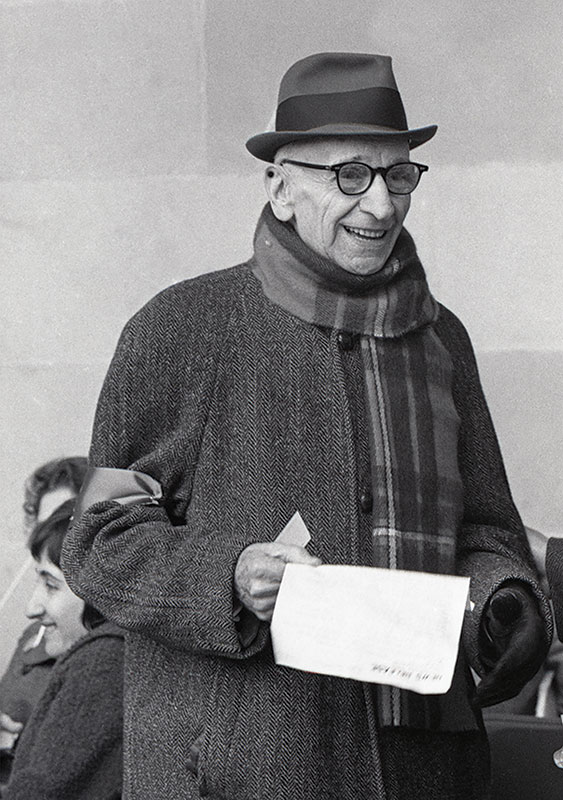

Throughout his tenure as director, Muste was very clear that the college should not shy away from questioning the AFL’s politics and strategy. He took care to ensure the college’s political independence, thanks largely to financing from the Garland Fund, an essential source of left-wing philanthropy in the early 1900s. The aim was for students and faculty to criticize from a place of commitment—and from a place of frank uncertainty. “In order to be worthwhile,” Muste wrote in 1929, “workers’ education must address itself to the actual needs and problems of the workers.” What those actual needs and problems were could be settled only by the workers themselves.

To that end, students at Brookwood enrolled in 15-week seminars on the fundamental political and social questions of the day. A seminar in “Advanced Economics” began with Marx and worked its way through comparisons of contemporary economic well-being in America and the Soviet Union. “Workers’ Political Action” asked students to figure out how the labor movement should engage in electoral politics. These classes were not lectures or trainings in disguise. “This morning I spoke on the ‘Relationship of Brookwooders to the Labor Movement,’” Ed Falkowski, a Pennsylvania mine worker who spent two years at Brookwood in the late 1920s, wrote in his journal. “[I said,] ‘We are not here so much to absorb theories as to take them apart and see what is in them.’… The talk went very well, provoking comment hot and cold…. The rest of the day I was being buttonholed by those [students] who disagreed with me.”

For Falkowski and thousands of others, the labor colleges were a place for good-faith discussions and debates about what kind of movement they wanted to build. As Arthur Gleason, a labor journalist, wrote in a pamphlet surveying the movement in its early stages:

This is the heart of workers’ education—the class financed on trade union money, the teacher a comrade, the method discussion, the subject the social sciences, the aim an understanding of life and the remoulding of the scheme of things.

That, after all, was the point. Workers’ education mattered to the extent that its students applied their learning, Muste argued, “in the actual work they did in unions.” And so in the mid-1930s, when the combination of an unbearable depression and a (warily) labor-friendly Roosevelt administration opened up new channels for worker action, Brookwooders streamed into the field. Two graduates went to Toledo to lead a strike at the Electric Auto-Lite Company, organized in part by Muste himself, that would kick off the historic strike wave of 1934. Clinton Golden, a machinist who served as Brookwood’s faculty recruiter, helped found the Steel Workers Organizing Committee in 1936. A Brookwood economics professor, Katherine Ellickson, supported a radical wing of the United Mine Workers and eventually became a top official of the CIO. Brookwood alumni, the vast majority of them rank-and-file workers, helped lead crucial strikes at mines in New Mexico, steel mills in West Virginia, rubber plants in Ohio—and the sit-down strikes of 1936 and 1937.

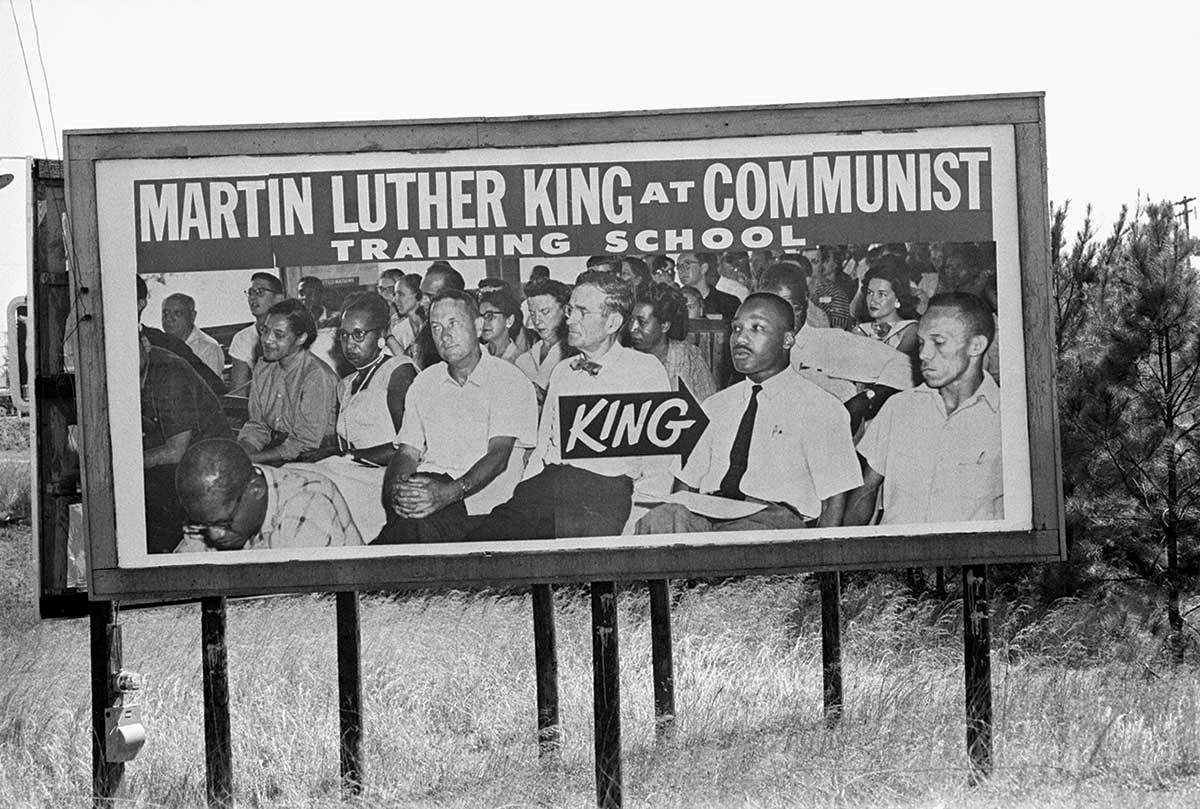

More than that: The labor colleges of the 1920s and ’30s sowed the seeds of many lefts, including some that bore fruit long after the end of the New Deal. The Highlander Folk School in Tennessee, for instance, is today better known as an incubator for the civil rights movement—Rosa Parks, Martin Luther King Jr., and dozens of other leaders studied there. But it was founded in 1932 as a labor college on the Brookwood model. (Elizabeth Hawes, who became the extension director for Highlander, was a Brookwood alum.) The civil rights lawyer Pauli Murray studied at Brookwood in 1936, during the heat of the sit-downs and with many of her classmates bound for Spain to fight fascists. “I was catapulted,” she later recalled, “into a radical stance.”

The tidal wave of progressive unionism in the late 1930s was the culmination of Brookwood’s mission. It was also, ironically, part of its downfall. The founding of the CIO and the explosion of worker unrest in the late ’30s drew would-be students onto the shop floor. This attrition, combined with growing internal strife—attacks from AFL conservatives and, as the Popular Front began to fracture, Communists—proved to be fatal, and Brookwood shut down in 1937. Almost all of the other labor colleges folded around the same time, with the notable exception of Highlander.““Having survived Labor’s poverty,” observed a Time magazine article, “Brookwood was killed by Labor’s prosperity.”

This was true in ways that Time could not have foreseen. As organized labor grew stronger after World War II, it also grew more conservative. Workers’ education programs generated politics that were more radical than most union leaders, whether for fear of anti-communist crackdowns or because of their own convictions, could stand. In their place, they built programs focused on skills training, teaching members how to reinforce a regime of collective bargaining that became the limit of the labor movement’s vision. (Meanwhile, universities established “labor studies” programs that, however well-intentioned, scrutinized unions as players in interest-group politics: better living through social science.) By the 1950s, when union density in America peaked, the workers’ education movement had all but disappeared.

Workers’ education programs were canaries in the coal mine. Their demise foretold the processes of deradicalization and counterrevolution that began to hollow out the core of the labor movement in the late 1940s onward. Whether such growth could have been achieved without labor’s acquiescence to a Cold War order is a question that historians continue to debate. What is clear is that the turn away from workers’ education came at an inopportune time. In the early 20th century, socialism and radical democratic movements were both live models and unrealized hopes for the labor movement to draw from. By the 1980s, neoliberalism and the Cold War had obscured those radical alternatives from view. (I wonder whether, in a strange way, the turn from radical education also chimed with the Alinskyite belief that people could be politicized through organizing alone—a belief that still persists today.) Organized labor neglected the project of building a competing worldview at the precise moment when workers’ access to alternate political visions through other social channels disappeared.

What could a workers’ education movement look like today? What would it take to build one on a scale that matches—and then exceeds—the Brookwood moment? We are asking these questions as we gear up for Worker Power’s summer education program in Phoenix, now in its second year. For an entire month, 24 members from unions and organizations all over the country will gather every morning for a seminar in the Brookwood style, each led by a different instructor-activist. (One promising opening for workers’ education: Many young academics have now experienced a union in graduate school.) In the afternoon, they’ll knock on doors as part of Worker Power and Unite Here Local 11’s canvassing operation for the general election. The idea is to blend learning and action, even as the two push up against each other—in this case, to work alongside Democrats while teaching beyond, and sometimes against, the party platform. Our first session, in 2022, was hardly perfect. But when it worked—the flash of recognition as an opaque historical process came into relief, and the powerful confidence that followed—it was amazing to see.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →This is one model. We will need many others. We will need programs that bridge the gaps in education, wealth, ethnicity, race, and ideology that exist between and even within unions. There must be strikes to go to and organizing campaigns to join (a reminder that the current surge in both is critically important). Unions and philanthropists will need to support these programs while granting them genuine independence. We will need classes on the climate crisis, on neoliberalism and financialization, on the politics of immigration and the history of colonialism, on the history of how unions have become so legally and politically constrained—and on what it might look like for that not to be the case. Most of all, we will need to figure out how to give new meaning to radical and genuinely internationalist labor politics for rank-and-file workers when “socialism” remains, by and large, a meaningless or even a pejorative term.

All of which is to say that a workers’ education movement today cannot simply mirror the Brookwoods of a century ago. An alternative to capitalism is harder to envisage now than it was four years after the Bolshevik Revolution. The legal regime around unions, so freeing in the 1930s, now restricts us to a set of narrow goals. And now, unlike then, we have to contend with what Mike Davis called the “barren marriage” between labor and the Democratic Party. Whether these differences put us in a better or worse situation than we were a century ago is almost beside the point; they put us in a different one. And so, even if the goal of a workers’ education movement remains the same—”a collective practice aimed at both arming the masses with the capacities for recognizing their place in the world, and producing a new sense of themselves as agents,” as the theorist Adom Getachew has recently put it—the shape it takes will be new. It may even involve working to transcend those structures that earlier generations of labor leftists fought to secure. We will have to find out as we go.