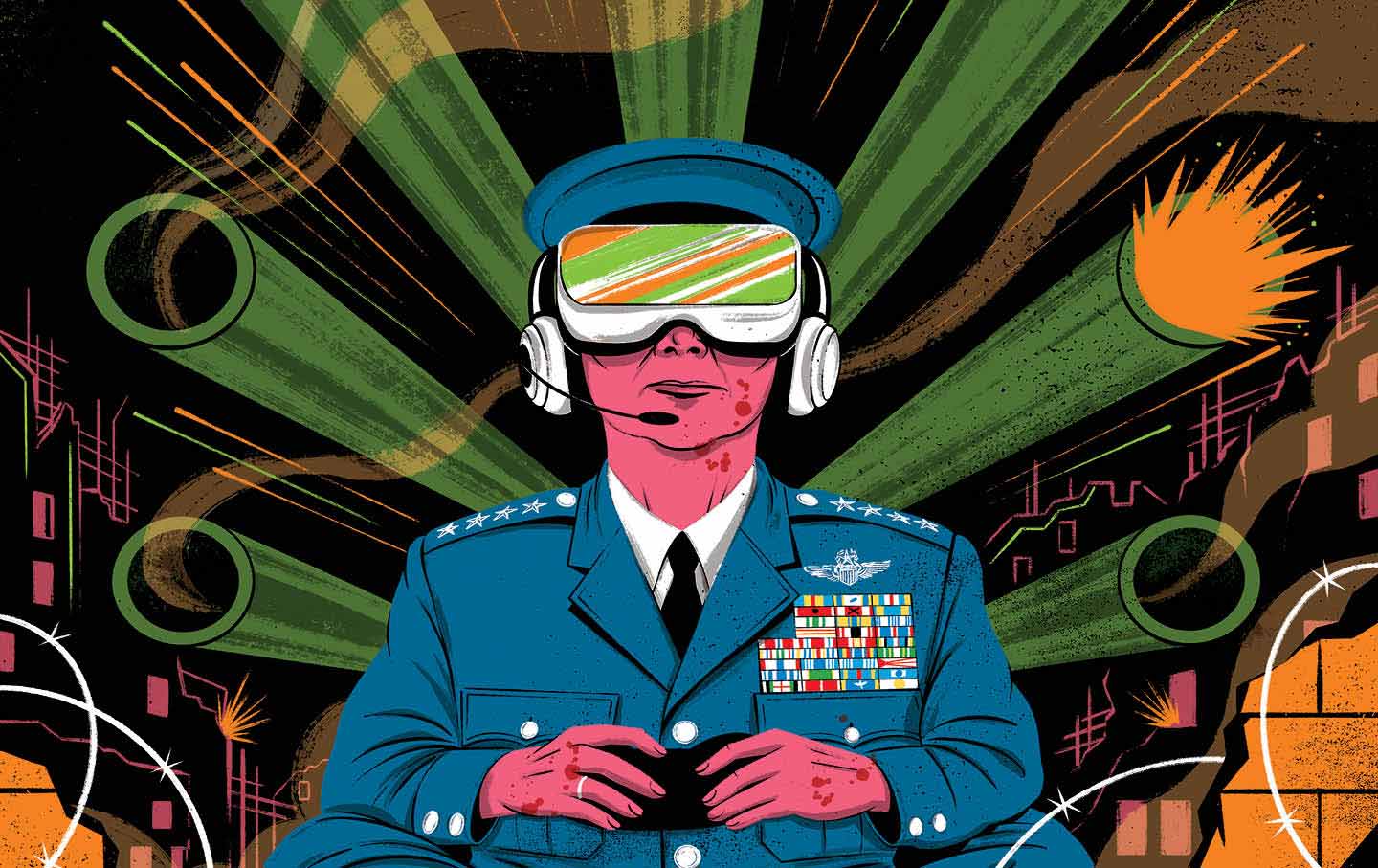

Inside the weird synergies that launched the videogaming industry---and made the Pentagon fantasies in Call of Duty its stock in trade.

Illustration by Adrià Fruitós.

Ever since Donald Trump established the US Space Force in 2019, it’s been hard to work out just what its mission is, beyond showcasing the Pentagon’s cosmic ambitions. Yet the Space Force has distinguished itself in one key field: competitive video gaming. In 2020, a team of Space Force gamers narrowly defeated a group from the British Royal Air Force in that year’s Call of Duty Endowment (C.O.D.E.) Bowl, the first such tournament pitting military branches from around the world against one another. The Space Force repeated the feat a year later—and it celebrated its victory by launching its trophy into space. In another contest this August, the Space Force team prevailed on a larger stage, when a group of its soldiers stationed in Colorado claimed the CONUS Esports championship belt in a nationwide Call of Duty showdown hosted at the Eglin Air Force Base Gaming Complex.

The nexus between gaming culture and military achievement is a long-standing one. Indeed, the interservice competitions that have propelled the Space Force into the gaming elite were sponsored by a nonprofit organization created by Activision Blizzard, the parent company of Call of Duty, to promote employment initiatives for US veterans returning to civilian life. But the deeper history of gaming and war-making is neither as benign nor as spectacular as these collaborations suggest. It’s hardly an exaggeration to say that today’s global gaming colossus is the offspring of the Pentagon; by some measures, the nearly $350 billion gaming industry is one of the Defense Department’s most significant innovations since the end of the Cold War. Soldiers and civilians alike rally to the embattled cause of American militarism every time they take a controller in hand to try out a new first-person-shooter (FPS) franchise.

For ready confirmation of this state-and-gaming synergy, look no further than Black Ops 6, the latest installment in the Call of Duty series, released in late October. Today, the Call of Duty franchise is a fixture in the gaming world—and a massively successful one at that. The original Call of Duty was released more than two decades ago and set in the Second World War. But like the American military might unleashed in that conflict, subsequent games quickly moved on to darker, more morally equivocal battlefronts. Black Ops, a subseries within the Call of Duty universe that debuted in 2010, is emblematic of this shift. The first Black Ops threw gamers into a 1960s Cold War fantasia of grisly campaigns in Cuba, Vietnam, and Russia. The game follows CIA operative Alex Mason as he tries to reclaim his damaged memory and root out a network of communist sleeper agents scheming to unleash chemical weapons on an unsuspecting American public. While Mason is long since dead in Black Ops 6, a clutch of other CIA hands carries on his legacy in the even murkier post–Cold War order of the early ’90s, as sparks fly in the Persian Gulf. Several of them have been accused of treason to the American cause, and the game’s leading man, Frank Woods, is enlisted to unearth a labyrinthine conspiracy brewing within the US security state.

Familiar political leaders populate this wilderness of mirrors: Saddam Hussein, George H.W. Bush, Bill Clinton, Margaret Thatcher—all are involved in the grand plot. A press release from the game’s publisher gives existential currency to the game’s pivot toward more recent military history, telling users that it’s “time to fight the very machine that created” its protagonists. There are also zombie hordes to be extinguished for players who are into that sort of thing. And early promotional campaigns dote on the hyperrealistic gunplay, blood-splattered lens and all, as players knock off a rotating cast of terrorists, rogue-state military chieftains, and turncoat spies.

The game’s mood of geopolitical confusion might appear to be an overly clever plot gimmick—Activision’s PR copy likens it to a “dynamic and intense spy thriller” pitting solitary would-be heroes against an emergent world order where they’re “never sure who to trust, and what is real.” But uncertainty is precisely what keeps players engaged and vigilantly trigger-happy: The only trustworthy broker in Black Ops 6 is, in most cases, a dead one.

Black Ops 6’s suspicion-filled netherworld is a fitting gloss on a generation’s worth of harrowing intrigue on the frontiers of American war-making. With regime-change initiatives in Iraq and Afghanistan falling into subcontracted chaos, and the wars in Gaza and Lebanon a human rights horror masquerading as Israeli self-defense, American defense intellectuals might recognize Frank Woods’s disorientation as he launches into a fresh killing spree. In this sense, the Space Force’s Call of Duty champs might well be able to claim their gaming belts as a central advance in their combat training.

The “realistic” flourishes that heighten the combat experience in Black Ops 6 took shape under a Pentagon brief, one that predates the game’s early-’90s setting. In fact, when the modern gaming industry was coming online, the Department of Defense already had skin in the game. The concept of simulated warfare, which has inspired game designers and war planners alike, reaches back to Pentagon-led efforts to re-create a battle from the first Gulf War—and, earlier yet, to attempts to rehabilitate the US Armed Forces in the aftermath of their defeat in Vietnam. By creating readily executed models of combat on simulation consoles, US defense officials wanted to identify weak spots in military strategy and counterinsurgency planning, rendering mobilizations leaner and more efficient in the process.

Instead, what they produced was an influential and commercialized version of warfare for warfare’s sake, launched through Pentagon contracts with Silicon Valley’s rising mogul caste. By the time the first FPS gaming franchises debuted in the early ’90s, the basic model of the gaming/soldiering experience had been forged, auguring an interlocking vision of warfare as glorified gaming—and vice versa.

And Call of Duty might be the culmination of the digital marketing world’s efforts to capitalize on real-world military planning. For more than a decade, it’s been the best-selling franchise among the estimated 212 million Americans who play video games regularly. (It had clocked $30 billion in lifetime revenue by 2022.) And the FPS fantasies that make up the game’s storylines are steeped in the gaming industry’s cozy relationship with the national security state. Raven Software, Call of Duty’s primary developer, is an outgrowth of the FPS genre’s inventor, iD Software, which drew heavily on military tech in its designs. Oliver North, the famous Iran-contra conspirator, played an advisory role on Call of Duty: Black Ops II (whose plotline toggles between the 1980s and 2025 as players hunt a fictional Nicaraguan narco-terrorist) and even makes a cameo appearance in the game.

The paranoid medley of fact and fiction that characterizes the Black Ops series underlines an important point about the evolution of modern gaming. The military’s integral role in creating the look and feel of video gaming—along with the Pentagon’s running audition for successor conflicts to the Cold War—has helped engineer the ideological surround of the FPS world. A military worldview has been spreading within the gaming industry for decades, to the extent that gaming competitions become recruitment portals for the US military. Appreciating the depth of the alliance between the Pentagon and the entertainment industry is integral to understanding the conjoined fortunes of America’s permanent war economy and the multibillion-dollar gaming business.

Ties between entertainment and defense predate the Cold War, but that conflict would become their great moment of convergence. Those tense decades of proxy confrontations with the Soviet Union placed a premium on military preparedness, both in civilian life and on the frontiers of superpower conflict. During the 1950s and ’60s, the Department of Defense sunk vast sums into the nascent computer industry to meet the requirements of the nation’s missile and satellite defense systems. A little-noted byproduct of this union was the debut of one of the world’s first video games in 1962: On a computer the size of three refrigerators, paid for with a chunk of Pentagon largesse, MIT students developed a game bearing a title appropriately couched in cosmic imperialism—Spacewar! Helming a flickering, pixelated spacecraft, players navigated a rudimentary starscape, blasting away at a steady barrage of enemy vessels.

But US priorities would become more terrestrial during the 1970s. The American military defeat in Vietnam provoked budget cuts at the Pentagon and soul-searching among our strategists of armed conflict. This inward turn didn’t last long—or rather, it found new expression in a military obsession with a revolving suite of emerging gadgetry. Military planners studied the performance of the Israel Defense Forces’ technology in the 1973 Arab-Israeli War and staged war-gaming exercises in huge tracts of the California desert. The ideological mission was clear: conquer the morale-sapping “Vietnam syndrome” and restore American prestige through decisive military advantages and victories.

The Pentagon’s first attempts at simulated warfare were gargantuan affairs. Standing in some instances three stories high, the early combat simulation consoles could cost twice as much as the hardware they modeled. (Advanced flight simulator systems ran a whopping $30 million to $35 million; the individual aircraft itself could be had for about $18 million.) With its balance sheets coming under congressional scrutiny in the mid-’70s, the Pentagon rolled out a new PR offensive via SIMNET, its distributed simulator networking project, to be developed by the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, or DARPA. The idea was to produce a more portable and easily updated platform for soldiers to experience virtual combat—the next generation of synthetic, computerized combat training, sold on its frugality as much as its strategic necessity.

In 1980, an Atari game called Battlezone piqued the interest of the Army’s Training and Doctrine Command, which, chasing low-cost, high-tech solutions, had been trying to figure out how to use arcade-game technology to its advantage. Battlezone’s designers were recruited to develop the Bradley trainer for the Army—a large-scale simulator replicating the controls of its namesake combat vehicle. To DARPA, the Bradley trainer represented a promising, if rudimentary, step toward a fully virtual training environment that individual participants could patch into.

Jack Thorpe, an Air Force colonel, had been on the simulation beat for nearly a decade. He’d proposed a far-reaching 25-year development plan for advanced simulated combat in the fall of 1978, after which DARPA had brought him into the fold. In pioneering the SIMNET initiative, Thorpe tapped into the Pentagon’s post-Vietnam ethos of innovation: The system should augment, not replace, its real-world corollaries, he argued. Rather than try to replicate an entire piece of hardware, it would simulate the experience of using that hardware. Answering the military’s then-chief preoccupations with productivity and efficiency, simulation could thus provide lessons otherwise impossible to come by in peacetime; SIMNET was streamlined to reduce its irksome bulk and steep price tags, leaving only essential knowledge intact. This design philosophy would become the basis of the burgeoning gaming industry.

In 1982, SIMNET’s development gathered serious momentum, and by the end of the decade, it had gone online. Along the way, Pentagon officials effectively built the first “massively multiplayer online role-playing game” (MMORPG): The essential knowledge that Thorpe and his colleagues said that SIMNET would promote was related to group-based, rather than individual, training experience. Users might be wired into physically distant terminals, but they were nonetheless a brigade, interfacing in real time inside the same cramped, tense, albeit digital tank cabin. This experience would, according to Thorpe and his division of military-tech evangelists, translate into military success down the road. And so Thorpe’s vision came to pass, in the simulation-driven corridors of the Pentagon. In trying to forecast the future, Thorpe’s planning division had created it.

From our vantage point, four decades into the computing revolution, SIMNET’s animation—cube-like and clunky by even the humblest standards—doesn’t begin to approach what we would consider “realism” in terms of user experience. And it suffered from what computer engineers call “latency,” the delay between an input and its execution on-screen.

Still, SIMNET marked an important design milestone, charting a course for modern video and war gaming: Right out of the gate, it foreshadowed the vanishing boundary between gaming and war. Reality, or an idea of it, could be collapsed into a compact unit and made fully scalable, replicable, and tweakable for individual users. Speaking to Wired in 1997, Duncan Miller, a project manager at Bolt Beranek & Newman in Cambridge, Massachusetts (the DARPA-approved outfit that was responsible for creating Arpanet, the forerunner of the Internet, and that had been contracted to program SIMNET), said that “much of what we think of as ‘out there’ is really internally constructed, coming from models running in our minds.”

This was a rather heady evocation of long-standing debates about how and whether humans apprehend reality, dating back to Plato, but Miller’s theory was entirely in line with the Department of Defense’s efforts to reimagine warfare from the ground up. It’s perhaps also relevant that Miller was a member of the Society of American Magicians; what he was describing was essentially a conjuring trick. For gaming pioneers and their successors, cognition was itself a form of simulation. The only difference, in Miller’s telling, was that what we are all prompted to accept as the world “out there” was now taking crude shape within the Pentagon’s processors.

In February 1991, during the American ground invasion in the Gulf War, Captain H.R. McMaster (better known today for his brief stint as national security adviser in the Trump administration) led the Second Armored Cavalry Regiment against the Iraqi Republican Guard’s Tawakalna Division. The ensuing action—named “73 Easting” for a line on a map used to track the troops’ advance through the desert—saw the Americans emerge victorious in just 22 minutes, even though their forces were outnumbered and they were besieged by a vicious sandstorm.

Indeed, 73 Easting was remarkable not just for its display of military might; the Pentagon brass also touted the operation as a definitive confirmation of Jack Thorpe’s vision. During preparations for the invasion, 80 percent of the leaders of the US ground forces in Iraq had trained on early SIMNET builds. But more important, by mapping out this real-life battle on a virtual grid a few months later, Pentagon war planners unleashed what would become the key innovation of the military-themed gaming industry: a lifelike experience of combat scaled to individual users.

To help them prepare 73 Easting for its SIMNET debut, military planners demanded heaps of data. That’s why, just a month later, McMaster went back in Iraq to retrace his division’s progression across the same desert battlefield. McMaster’s confrontation with the Republican Guard would become a prototype for a new generation of simulated warfare. At the request of the Army’s vice chief of staff, Gen. Gordon Sullivan, McMaster and nearly every other officer involved in the fighting were convened for interviews. Pentagon officials amassed officers’ diaries and personal tape recordings, and dutifully recorded tracks in the sand left by military vehicles. Tanks carried black boxes during combat that were later used to confirm their exact ground positions. Missiles left fragile wire trails revealing their trajectories and explosive descents. War planners reviewed satellite images and radio transmissions documenting the action. At the Institute for Defense Analyses’ Simulation Center in Alexandria, Virginia, technicians worked for nine months reassembling the digital shards of the first Gulf War.

Events as they had actually happened were etched into electronic perpetuity—but the results enabled military war-gamers to alter the fabric of reality, entertaining infinite what-ifs and counterfactuals. At the 1991 Interservice/Industry Training, System and Education Conference (I/ITSEC)—an annual Pentagon-organized military-tech expo that brings together representatives of the armed services, academia, and industry—Thorpe and his colleagues debuted a videotape chronicle of “The Reconstruction of the Battle of 73 Easting.” According to one officer, this pivotal digital archive signaled “group training at the combat level like we’ve never had before…. We can test future ideas, concepts, tactics, doctrine, and vehicles because we now have a benchmark that’s rooted in ground truth.” As with any good video game, the endless replayability of the virtual version of 73 Easting was pivotal to its success.

The following year, DARPA’s whiz kids spliced together hundreds of pieces of computer hardware at the eleventh hour at I/ITSEC. Preparing to unveil a bigger and better SIMNET before an enraptured crowd of military buyers and tech colleagues, the Pentagon’s vanguard corps of computer geeks snaked network connections throughout the convention center’s auditorium early into the morning. Despite a few hiccups—errant connections and the like—the computer-mediated version of 73 Easting captivated the audience by both replicating real-world combat and gaming out alternate scenarios on the fly. One giddy attendee bragged that it was the “first time where industry and government got together and were able to demonstrate the interoperability of various applications on one medium.” In English, this meant that the world was on the verge of beholding the video-gaming universe as we’ve come to know it. Before long, war games would cut across time and space: The Army initially procured 260 SIMNET-capable simulators and distributed them to 11 military sites, from the Mojave to Bavaria. By 2000, Thorpe speculated, there would likely be thousands more.

If the beginning of the Cold War set the simulation boom in motion, then the conflict’s end forced it to evolve. The threat of a massive “peace dividend”—or what the military more ominously called “drawdown”—meant that Pentagon spending could be reined in from Reagan-era highs. A new war-making mandate took shape as a result. Viewing large-scale, expensive land-based wars as a thing of the past, the military establishment embraced a tech-centric “revolution in military affairs” (RMA). From special operations to precision-guided munitions, clean and laser-like efficiency would now be the watchword for Pentagon outlays.

The panicked talk of a drawdown rapidly subsided. Preparation continually displaced action as the rollout of next-generation weapons and ever-larger training exercises droned on. Case in point: In 1995, the Army introduced a new planning mandate, Force XXI, under the rationale that in future US interventions involving two simultaneous major regional conflicts, “modernizing” would have to be achieved “through product improvement.”

From the nonstop broadcasts of bunker-buster explosives in January 1991 to the “shock and awe” opening salvos of the second Iraq invasion a dozen years later, the new tech directives issuing from the Pentagon were designed to overwhelm America’s pitiably outmatched enemies—all via the push of a button.

The inauguration of RMA pushed the military to reorganize in the manner of a data-driven corporation, even as it was underwritten by massive federal subsidies. As the end of the Cold War lifted the veil of secrecy from military research, the lines separating military contractors from their commercial counterparts all but vanished. By 1998, the Army’s budget for modeling and simulation programs had surpassed $2.25 billion. The historians of science Timothy Lenoir and Henry Lowood note that while this was a fraction of total defense spending, it turbocharged private-sector investment in modeling and simulation technologies, primarily because of the military’s new, looser contracting and procurement protocols. In 2000, Michael Macedonia, the chief scientist at what was then known as the Army Simulation, Training and Instrumentation Command (STRICOM), predicted that by “aggressively maneuvering to seize and expand their market share, the entertainment industry’s biggest players are shaping a twenty-first century in which consumer demand for entertainment—not grand science projects or military research—will drive computing innovation.”

More than anything else, the massively popular 1994 first-person-shooter game Doom II prefigured the new normal in the overlapping war-planning and gaming worlds. The first version was built on shareware, meaning that anyone who wanted to could modify its source code. The Marine Corps adapted the game into its own training platform called Marine Doom, morphing Doom II’s space fantasy into a close-quarters urban combat simulator, with the designs of the battle scenes’ “bad guys” cribbed from G.I. Joe action figures.

Marine Doom didn’t entirely catch on as a training tool; it was more of a proof of concept than anything else, used to gin up enthusiasm for the military’s larger simulation development programs. And as one Marine suggested to Wired, the game would serve as an extracurricular component of “professional military education.” In other words, it drove home the benefits of a symbiotic “military-entertainment complex,” in science-fiction author Bruce Sterling’s formulation.

Military theorists were quick to pick up on the implications. Michael Zyda, a professor at the Naval Postgraduate School in Monterey, California, held a workshop in October 1996 to explore the partnership that was taking shape between the Pentagon and the digital entertainment sector, documented in a report titled “Modeling and Simulation: Linking Entertainment and Defense.” Though Zyda lamented that “the flows of technology between the defense and entertainment industries have largely been uncoordinated,” he predicted that would soon change. Representatives from companies like MäK, Spectrum HoloByte, and Silicon Graphics—which were all part of DARPA’s extended universe of public-private collaboration in the increasingly indistinguishable fields of gaming and combat simulation—signed on to Zyda’s plan.

Zyda’s vision of entertainment and military crossovers landed him a $45 million five-year start-up grant from the Army in 1999 to launch the Institute for Creative Technologies at the University of Southern California. Beyond the ICT, money splashed around liberally in this brave new digital world, providing an ascendant class of techies with ample opportunities to cash in. Companies like Real3D and Viewpoint DataLabs lacked name recognition in Silicon Valley, but they made up for it in market synergy. The former was a Lockheed spin-off, created after the aerospace giant’s merger with Martin Marietta in 1995. Real3D’s goal was to market graphics technology for civilian use, which led to a profitable partnership with the gaming company Sega. Viewpoint DataLabs, meanwhile, hawked “DataSets”—3D computer renderings that provide the underlying structures for digital animations—at military trade fairs and to film studios for use in splashy war and sci-fi films. (Viewpoint contributed the F-18 fighter jets for the 1998 blockbuster Independence Day.) Putting a bow on the whole endeavor, Zyda acknowledged earlier collaborations with executives from Pixar Animation Studios and Walt Disney Imagineering; for their part, these entertainment chieftains later admitted that “funding from defense agencies such as DARPA had a significant effect on the development of fundamental technologies critical to defense and entertainment.”

For members of the Pentagon brass, this arrangement also satisfied a psychological need. Military techno-fantasies lent war planners a new sense of purpose and broke the grip of anxiety that had set them adrift at the Cold War’s end. A simulation race could supersede the arms race: Why search for an existential enemy when you could render one on-screen? STRICOM’s motto declared that “All But War Is Simulation”—but the ubiquity of both simulated war-gaming and Pentagon-sanctioned FPS dramas soon gave the lie to that claim. Jack Thorpe’s designs succumbed in short order to a potent, endlessly renewable push to make real and simulated battle practically interchangeable.

In late 2004, the investigative journalist Gary Webb, writing in the Sacramento News & Review, observed a new phenomenon in online gaming: More than 4 million users were playing an online, PC-based first-person-shooter game produced by the US government. America’s Army had been released two years earlier, for free, on the first Fourth of July after 9/11. “The goal,” according to Zyda, who had a hand in its development, “was to give [players] a synthetic experience of being in the Army.”

The public and media reaction was, according to the Army, “overwhelmingly positive.” A reviewer wrote in Salon that America’s Army might help “create the wartime culture that is so desperately needed now”—a “‘Why We Fight’ for the digital generation.” The Army soon signed a contract with Ubisoft, a French video game publisher, to bring America’s Army to commercial consoles. “We’d like to reach a broader audience,” Col. Casey Wardynski, the military economist who came up with the idea for the game, explained. “Consoles get you there. For every PC gamer, there are four console gamers.” Webb reported that America’s Army was also an aptitude test, collecting data to help the Army figure out what kinds of jobs to give potential recruits. As the Los Angeles Times announced in the wake of the game’s release, “Uncle ‘Sim’ Wants You.” It was a logical, if dystopian, next step.

There’s an oft-repeated line that military FPS games are propaganda, designed to manufacture consent for both specific wars and militarism writ large. Undoubtedly, America’s Army, along with Full Spectrum Warrior—also developed at the ICT as a training and recruitment tool—confirm that this has been true at least some of the time. But these claims also tend to have an air of neo-Luddism or moral panic, glossing over the fact that at a certain point, both entertainment and defense concerns slipped out of the war planners’ brief and further into the black hole that is the market.

Like any speculative technology, simulation has been an extended exercise in the hedging of bets. The 9/11 attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon, together with the United States’ ensuing Global War on Terror, reinvigorated the nation’s sense of military mission and, for the defense establishment, reaffirmed the RMA’s core lessons, namely that future wars would look less and less familiar. Training—with a heavy emphasis on simulation—could in theory make the black-box scenarios assailing the Pentagon more knowable.

But the benefits of the new digital arms race have been unclear at best. On the one hand, in terms of sheer violence, it’s scarcely made warfare leaner and more efficient, as measured by the grim metric of mass death (at least for non-Americans). The Costs of War Project at Brown University estimates that at least 4.5 million people have died directly and indirectly as a result of the post-9/11 wars. On the other hand, the military-industrial complex’s most fervent techno-optimists have made out like bandits. That’s the clear lesson of the newest turn in militarized gaming: Call of Duty is just one successful war game among many, all of which reverently update and repurpose the ideology and iconography of American imperial conquest. Regardless of whether you endorse the version of warfare these games present, you are, on some level, liable to accept it as true: The history can be bunk so long as the players buy into the violence.

At the same time, like the Space Force, the Army now sponsors an esports team out of Fort Knox. In a strange Möbius-strip twist, the Kentucky installation that once hosted SIMNET exercises now livestreams a crop of professional gamers on Twitch. Not to be outdone, the Navy reserves as much as 5 percent of its recruiting budget for similar initiatives, according to The Guardian. And in 2020, fake links on the Army’s esports channel advertised prize giveaways that redirected viewers to recruiting pages. “Esports is just an avenue to start a conversation,” as Maj. Gen. Frank Muth told an esports correspondent, before furnishing an ideal model for such an exchange: “‘What do you do?’ ‘I’m in the Army.’”

Perhaps, as the political scientist James Der Derian has suggested, “Vietnam syndrome” was succeeded by “simulation syndrome.” As the military-entertainment synergies have ossified into a kind of path dependence, gaming engineers and war planners are increasingly overtaxed by the effort to meet the demand for reality-based experiences, continuously pushing the envelope to outpace the oversaturated sensibilities of their user base. Lurking beneath the surface, too, is the fact that if military technologies permeate civilian life, and if civilian technologies serve military purposes, then the militarization of the modern world may run more deeply than we would like to admit. This may not be the brand of revolution that either RMA boosters or the libertarian prophets of controlled digital chaos in the private sector bargained for. But if Call of Duty: Black Ops 6 is any indicator, that circuit won’t be broken anytime soon.

Jesse RobertsonJesse Robertson is a writer and a doctoral student in history at Harvard University.