We Just Witnessed the Biggest Supreme Court Power Grab Since 1803

The court has given itself nearly unlimited power over the administrative state, putting everything from environmental protections to workers’ rights at risk.

The US Supreme Court Building in Washington, DC.

(Valerie Plesch / Bloomberg via Getty Images)

In the biggest judicial power grab since 1803, the Supreme Court today overruled Chevron v. Natural Resources Defense Council, a 1984 case that instructed the judiciary to defer to the president and the president’s experts in executive agencies when determining how best to enforce laws passed by Congress. In so doing, the court gave itself nearly unlimited power over the administrative state and its regulatory agencies.

Now, if you’re not a lawyer, that probably sounds bad, but mainly in a technical sense. Regulatory agencies like the Environmental Protection Agency and the Securities and Exchange Commission issue influential but deeply complicated rules, so it makes sense that somebody should have final authority over whether and how to enforce those rules. Since we have already made the disastrous decision to allow the Supreme Court to tell us who gets to be president and what women can be forced to do with their bodies, it might not sound like that big of a leap to also let the court decide how much lead can leak into our drinking water or which predators are allowed to sell mortgages.

The thing is: The US Constitution, flawed though it is, has already answered the question of who gets to decide how to enforce our laws. The Constitution says, quite clearly, that Congress passes laws and the president enforces them. The Supreme Court, constitutionally speaking, has no role in determining whether Congress was right to pass the law, or if the executive branch is right to enforce it, or how presidents should use the authority granted to them by Congress. So, for instance, if Congress passes a Clean Air Act (which it did in in 1963) and the president creates an executive agency to enforce it (which President Richard Nixon did in 1970), then it’s really not up to the Supreme Court to say, “Well, actually, ‘clean air’ doesn’t mean what the EPA thinks it means.”

For an unelected panel of judges to come in, above the agencies, and tell them how the president is allowed to enforce laws is a perversion of the constitutional order and separation of powers—and a repudiation of democracy itself.

But repudiating democracy to expand its own power is exactly what the Supreme Court did today in its ruling in Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo, which overturned Chevron. In a 6-3 decision, which split exactly along party lines, Chief Justice John Roberts ruled that the courts—and, more particularly, his court and the people who have bought and paid for the justices on it—are the sole arbiters of which laws can be enforced and what enforcement of those laws must look like. Roberts ruled that courts, and only courts, are allowed to figure out what Congress meant to do and impose those interpretations on the rest of society. He wrote that “agencies have no special competence in resolving statutory ambiguities. Courts do.”

That is a naked power grab that places the court ahead of literal experts chosen by the president, who is the one elected official we all get to vote for. Who do you think has a “special competence” in resolving what the word “clean” means in the context of the “Clean Water” or “Clean Air” act—experts at the EPA or justices on Harlan Crow’s yacht? Who do you think has a special competence to resolve what “safe” working conditions require—experts at the Occupational Safety and Health Administration or justices who have never worked as much as a day at a job that requires them to be outside? Who do you think has a special competence to resolve what “equality” means under the Civil Rights Act for women in workplaces—experts at the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission or justices who have been accused of attempted rape?

Even if you do think, somehow, that judges are best positioned to determine how to enforce the laws passed by Congress, who in the hell gave them the power to do so? Not the Constitution. When Congress and the president talk about how to do the work of the people, and the Supreme Court butts in, the official constitutional response to the court is, “I don’t remember asking you a goddamn thing.”

Despite the actual structure of the Constitution and all of its amendments, the Supreme Court, as an institution, has fought to exceed the limits of its constitutional power from the very beginning. Its ruling in Loper Bright is only its latest and most brazen move to set itself up as the ultimate and final authority in the nation. As I said, the appropriate historical context for its ruling today is not 1984 and its Chevron decision but its 1803 ruling in Marbury v. Madison. It was then, back when the country was still in its swaddling blankets, that the Supreme Court declared itself the sole interpreter of the Constitution. The word “unconstitutional” appears nowhere in the Constitution, and the power to decide what is or is not constitutional was not given to the court in the Constitution or by any of the amendments. The court decided for itself that it had the power to revoke acts of Congress and declare actions by the president “unconstitutional,” and the elected branches went along with it.

Even now, this is perplexing. The court has no enforcement power of its own, so there’s no inherent reason either the president or Congress has to defer to its demands, other than by convention and tradition. Yet the normal thing is for the court to issue a ruling, after which the elected branches are expected to do all the work of bending themselves to the court’s will. Sometimes, presidents just ignore the court (as Andrew Jackson, Abraham Lincoln, and Franklin Delano Roosevelt did) and wait for the court to figure out that nobody cares. Other times, the legislature will ignore the court, or drag its feet before implementing the court’s rules (as Southern state legislatures did after Brown v. Board of Education, essentially refusing to desegregate until John F. Kennedy sent federal troops down to make them do it). But most of the time, the elected branches will largely do what the court tells it to do, even though nobody elected the court, and the Constitution doesn’t give the court the power to make the rules.

Sometimes, however, there will be a flash point when the Supreme Court grabs as much power as it can stuff in its pockets and dares anyone to stop them. That’s what happened in Marbury v. Madison, and that’s also what happened in 2000, after the court’s ruling in Bush v. Gore. In that case, the Supreme Court picked the president instead of letting Florida recount the votes of its people.

As in Marbury, the officials who were constitutionally empowered by the people just let the court have its way. Bill Clinton, the actual president at the time, accepted that the court could decide which votes were counted. Jeb Bush, who was the governor of Florida, accepted that the Supreme Court could pick his brother for president. George W. Bush gleefully accepted that the court could install him as president (even though Bush may have actually won the recount in Florida, and thus could have won the presidential election legitimately under a normal democratic process). And Al Gore conceded defeat to the Supreme Court.

Twenty-four years later, the ruling in Loper Bright effectively completes the suite of powers the Supreme Court has given itself to lord over everybody else. The court can now: veto acts of Congress as unconstitutional, decide who gets to be president, and decide what the president is allowed to do while in office.

I do not believe the court would have made the jump from picking the president to assuming the role and powers constitutionally given to the presidency if the conservative justices weren’t already sure that the people were too weak to stop them. But the conservatives were sure they could get away with today’s ruling because they already got away with a different case two years ago: Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization. Dobbs is critical because Dobbs involved the court taking away a popular, fundamental right for the first time in American history. No other case, not Marbury v. Madison, not Bush v. Gore, involved unelected, lifetime appointees revoking by fiat a right previously enjoyed by the American people.

And you know what happened to the Supreme Court after Dobbs? Nothing. Sure, a lot of people were and remained pissed. And yes, some political candidates have paid an electoral price for the court’s extremist ruling. But neither the people nor their elected representatives have done one solitary thing to stop the court, reform it, or take away its power. The court’s “approval rating” has gone down, but its budget has remained unchanged, and its power has remained unchecked.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →Not one justice has even been hauled in front of Congress to be questioned about the Dobbs ruling. (The fourth estate, the media, has also wholly failed to hold the court accountable for its actions.). Astute court watchers will note that barricades went up around the court in 2022 because the court anticipated a reaction to its revocation of reproductive rights—but no reaction happened. Today, there was no security presence as the court blithely gave itself ultimate authority over all laws and regulations. The court knows that the people are too addled and distracted to even raise a sustained protest against its rulings.

To call ourselves a “democracy” after today is a sick joke. We are not a democracy. We are a nation that is allowed to make suggestions to our nine rulers on the Supreme Court, but those rulers are the ones who get to decide which suggestions they accept and which ones they ignore. It is the opposite of the structure outlined in the Constitution—the one where the people, through their elected representatives, make the rules while the unelected court merely addresses conflicts between the two elected branches or between the elected federal officials and elected state officials.

Frankly, we don’t deserve democracy. We haven’t earned it. We haven’t fought to protect it, and what little we inherited from the heroic efforts of the civil rights generation we’ve pissed away on presidential “debates” and political candidates we’d like to have a beer with. The Supreme Court dominates our elected branches of government because our political leaders lack the strength to do otherwise. We deserve no better than the yoke the court has fashioned for us, because we are the ones putting it on.

I wish I had better news for you. I wish I could say, “We just have to clap very hard in the next election and Tinkerbell will live and restore Roe v. Wade.” But this isn’t a fairy tale. There is literally nothing that can be done to restore the rights the Supreme Court has taken away, or restore the power the Constitution gives to the people, other than reforming the Supreme Court and flooding it with justices who do not think they are kings. Court expansion is the only way to stop the Supreme Court. But to expand the court we have to elect Democrats, many of whom are also against court expansion. Then we have to push those Democrats to get rid of the filibuster, which many of them don’t want to do. Then we have to get Democrats to use their power. Then we have to get the Democratic president to put the right kinds of justices on the court. And we have to do it all over the unified objection of the Republican Party, the Christian right, the fossil fuel industry, the financial services industry, your racist uncle who watches Fox News, and Ice Cube.

That’s… probably not going to happen. And the Supreme Court knows it. They’re counting on it. They’re about to go on a summer-long vacation and leave us to have our reality-television show Democracy where the viewers place their votes but the producers pick the winners. When they come back in the fall, fattened by the “gratuities” they just declared it was legal for them to take, they’ll let us know who is allowed to be president again—and then get back to work taking away more of our rights.

Support independent journalism that exposes oligarchs and profiteers

Donald Trump’s cruel and chaotic second term is just getting started. In his first month back in office, Trump and his lackey Elon Musk (or is it the other way around?) have proven that nothing is safe from sacrifice at the altar of unchecked power and riches.

Only robust independent journalism can cut through the noise and offer clear-eyed reporting and analysis based on principle and conscience. That’s what The Nation has done for 160 years and that’s what we’re doing now.

Our independent journalism doesn’t allow injustice to go unnoticed or unchallenged—nor will we abandon hope for a better world. Our writers, editors, and fact-checkers are working relentlessly to keep you informed and empowered when so much of the media fails to do so out of credulity, fear, or fealty.

The Nation has seen unprecedented times before. We draw strength and guidance from our history of principled progressive journalism in times of crisis, and we are committed to continuing this legacy today.

We’re aiming to raise $25,000 during our Spring Fundraising Campaign to ensure that we have the resources to expose the oligarchs and profiteers attempting to loot our republic. Stand for bold independent journalism and donate to support The Nation today.

Onward,

Katrina vanden Heuvel

Editorial Director and Publisher, The Nation

More from The Nation

“I’m Terrified”: Trans-Feminine Athletes in Their Own Words “I’m Terrified”: Trans-Feminine Athletes in Their Own Words

In part two of a series, trans women athletes describe what it’s like to compete in the Trump era.

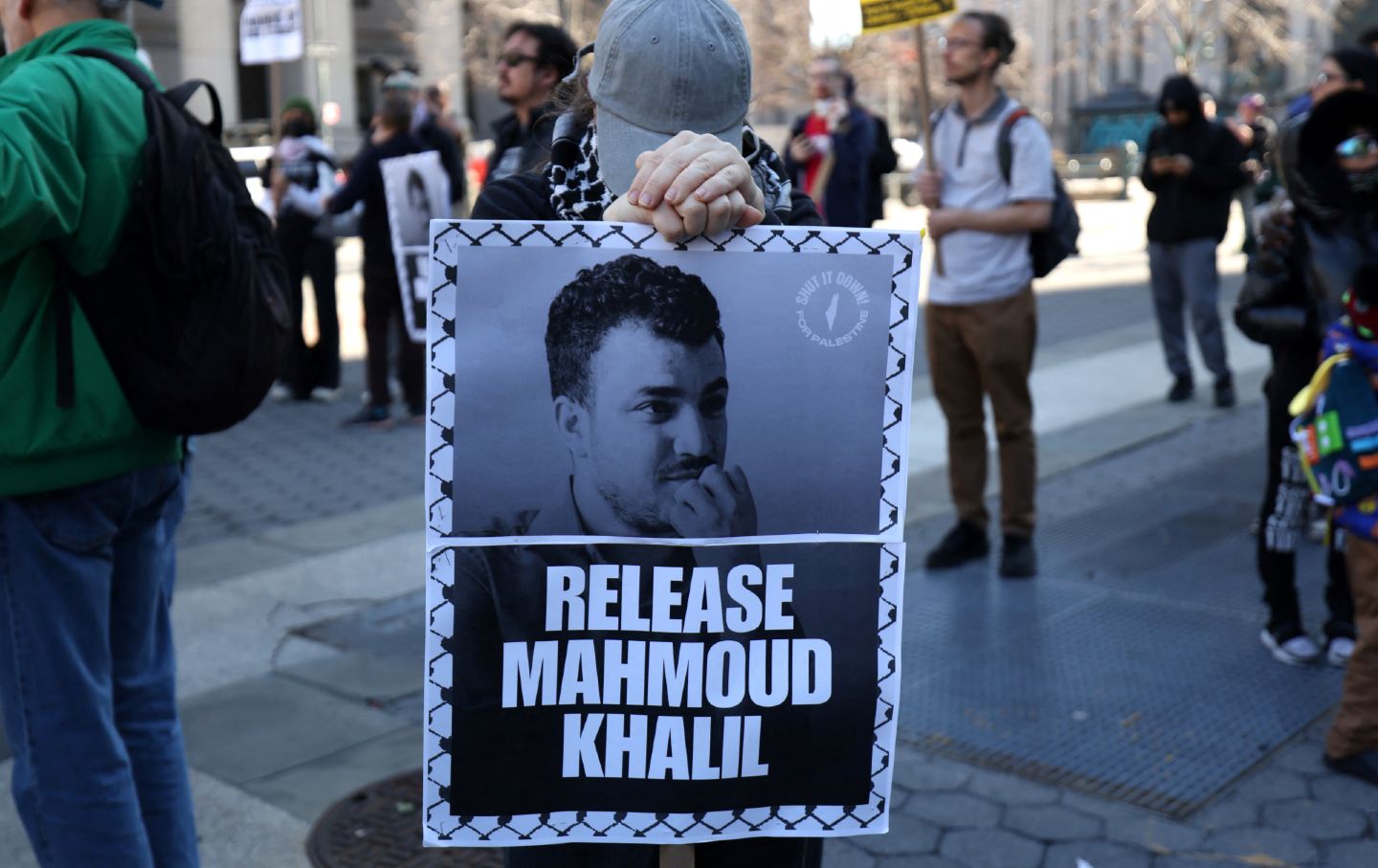

Columbia Is Betraying Its Students. We Must Change Course. Columbia Is Betraying Its Students. We Must Change Course.

The administration is choosing complicity over courage in the case of Mahmoud Khalil. It’s time for the faculty to demand a new path.

The Trans Cult Who Believes AI Will Either Save Us—or Kill Us All The Trans Cult Who Believes AI Will Either Save Us—or Kill Us All

What the Zizians, a trans vegan cult allegedly behind multiple murders, can teach us about radicalization and our tech-addled politics.

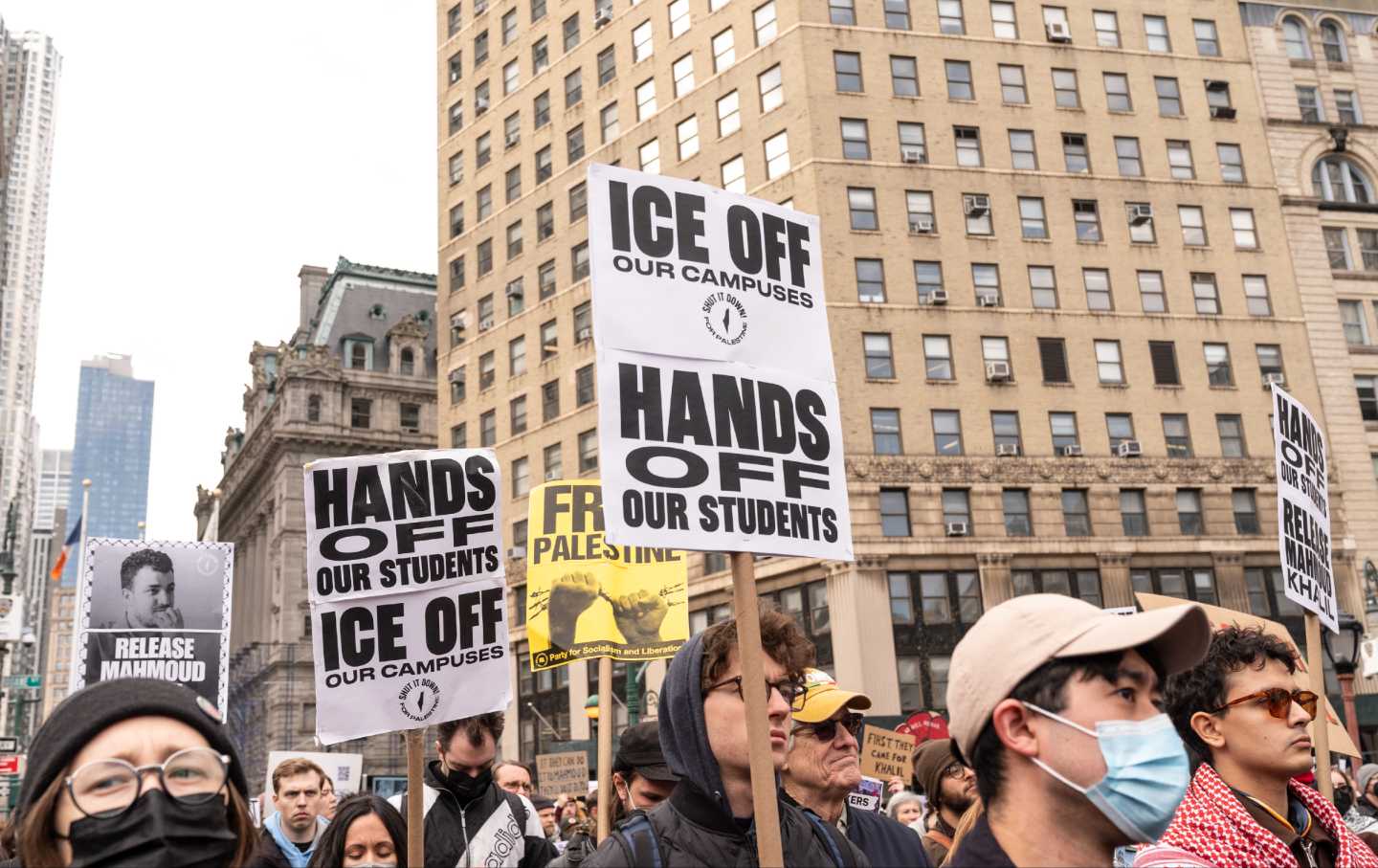

We Are Asking the Wrong Questions About Mahmoud Khalil’s Arrest We Are Asking the Wrong Questions About Mahmoud Khalil’s Arrest

The only relevant question is not “How can the government do this?” It is “How can we who oppose this fascist regime stop it?”

DOGE’s Private-Equity Playbook DOGE’s Private-Equity Playbook

Elon Musk's rampage through the government is a classic PE takeover, replete with bogus numbers and sociopathic executives.

White Flops Rejoice! White Flops Rejoice!

DEI is being snuffed out in DC. Mediocre whiteness reigns. And we’re all going to suffer for it.