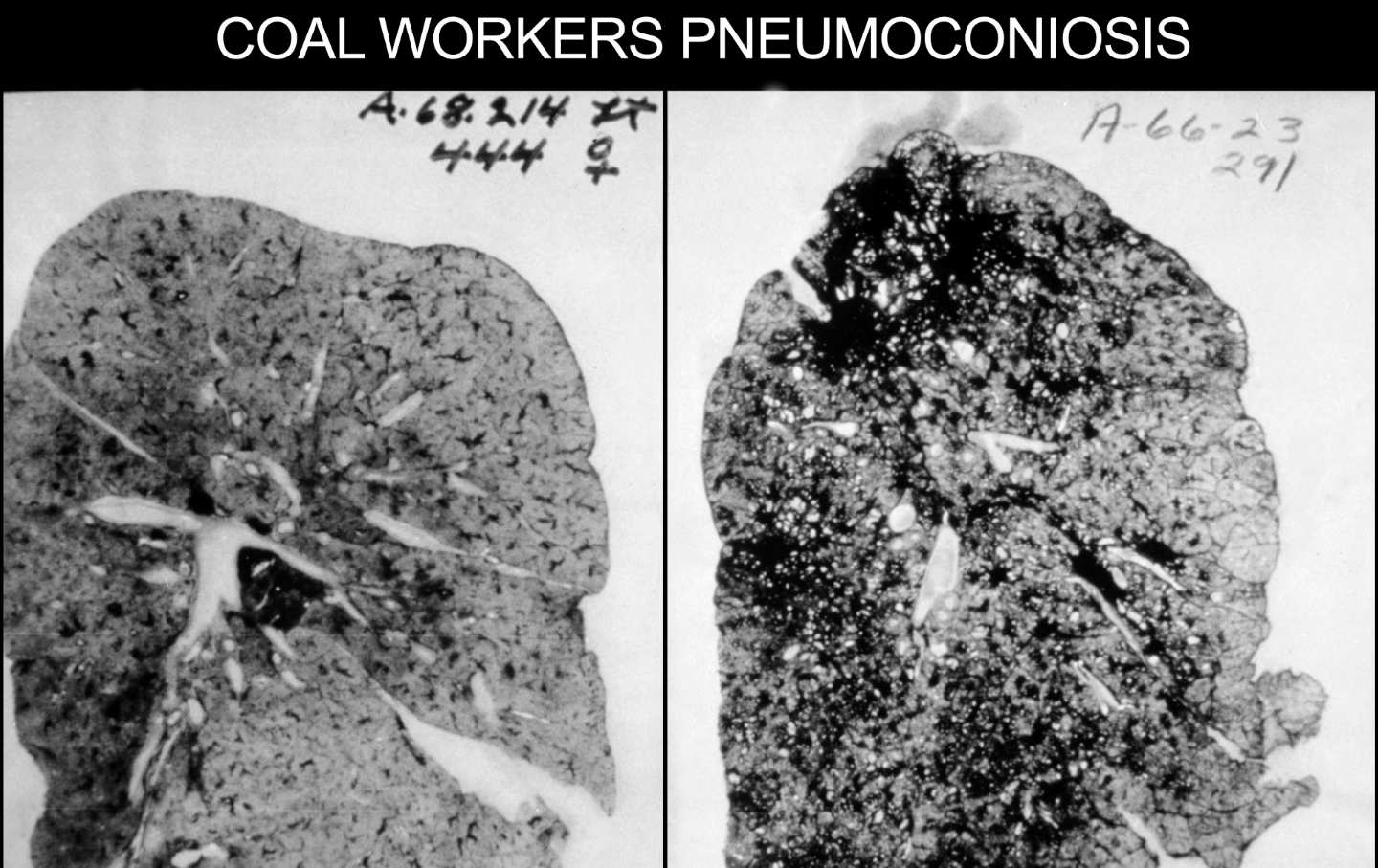

This occupational health image shows the lungs of a coal worker with Coal workers’ pneumoconiosis (CWP), commonly known as “black lung disease,” a job-related disease caused by continued exposure to excessive amounts of coal mine dust. This dust becomes imbedded in the lungs, causing them to harden, making breathing very difficult. Image courtesy of the CDC. (Smith Collection / Gado / Getty Images)

American coal miners are used to getting bad news, whether it’s of a buddy’s injury, an accident at their mine, a dip in coal prices, or word of yet another politician ignoring their needs. The profession—which still plays a complicated role in the nation’s economy, history, politics, and cultural imagination—remains incredibly dangerous, even as safety technologies have advanced and the number of jobs in the industry dwindles. The coal miners I’ve met through my coverage of the ongoing Warrior Met strike in Brookwood, Ala., and at labor events around the country are accustomed to disappointment, so when they do get a win, it’s a cause for celebration.

The 1,000 Warrior Met miners in Tuscaloosa County 15 months into their strike are still waiting for their victory party, but in Las Vegas in June, they and their coworkers around the country received an encouraging update on plans to address a much longer-running issue. On June 8, during the United Mine Workers of America (UMWA) 56th Constitutional Convention, a government official climbed onto a stage that had previously been filled by a parade of speechifying union officials and moving tributes to lost siblings, and shared some good news.

Chris Williamson, the assistant secretary of labor for Mine Safety and Health (MSHA), unveiled an ambitious silica enforcement initiative aimed at curbing miners’ exposure to respirable crystalline silica and its attendant health hazards. As the Department of Labor noted in a press release, when a worker cuts, saws, grinds, drills, or crushes rock and coal, silica fills the air, and the more a miner breathes in, the greater their risk of contracting a serious respiratory disease like silicosis, lung cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, or the dreaded coal workers’ pneumoconiosis, known as black lung.

A major plank of the new silica enforcement initiative will focus on repeat offenders, and operators who fail or refuse to improve face steep consequences. MSHA says it will conduct more spot inspections at coal and other mines with a history of citations or repeated silica overexposure to evaluate their health and safety conditions, and will expand its silica sampling program to gain more accurate assessments of the current risks. “Our first step is to work with them,” Williamson told me. “We will help you revise your ventilation plans or dust control plans to better protect miners, because we all benefit. That should be what we all want, right? Mine operators do better when they have healthy workers. … But at the end of the day, if they’re unwilling or that doesn’t happen, we have authority under existing law to require modifications to those plans, or if things get to a certain point, revoke them altogether.”

Black lung is a death sentence, and an ugly one. “I’ve watched people die of black lung, and I’ll just tell you, it’s the most awful sight you’ll ever see in your life,” Danny Whitt, a retired West Virginia coal miner and recording secretary of the UMWA Local 1440 in Matewan, W.Va., told me. “It’s like taking a fish out of water, and just laying them on a table, and watching them gasping for breath and dying. For a coal miner, if he dies with black lung complications, it’s a horrible death. They just smother.”

Whitt knows the subject well. The first time I met him was during last year’s Blair Mountain Centennial celebration; as we out-of-towners gathered in Local 1440’s cheerful, yellow-painted union hall, he sat on a dais and talked about the disease that’s been killing off his union brothers for decades. The bulk of the local’s membership is made up of retirees, many suffering from black lung, and each month, there are three or four more empty chairs. Whitt himself was diagnosed with the disease in 1988. The tall, genial Appalachian started working in the Mingo County coal mines in 1977, drawn in by good pay and the pull of tradition. He passed the required physical examination, which he described as rigorous—”They would go from head to toe”—but his clean bill of health wouldn’t last. “When I started, I didn’t have black lung, didn’t have any lung issues,” he told me. “But now I have all kinds of lung issues.”

In 1988, Whitt underwent a routine screening for silicosis, a type of pulmonary fibrosis caused by inhaling crystalline silica dust, and the doctors diagnosed him with black lung. The state of West Virginia deemed him 5 percent disabled by the disease—too low to qualify for any kind of benefits, but high enough for it to be a problem for Danny. Now, 34 years later, Whitt struggles to walk long distances, his energy levels have plummeted, and heat makes his symptoms more difficult to manage. Last year, when he took a blood gas test (which measures the oxygen levels in a patient’s blood, and is used to gauge lung and kidney function) his results came back at 81. “When Donald Trump contracted Covid, they said his blood oxygen got down to 96, and they were really worried about him,” Whitt told me. “What about a poor old coal miner who’s down in the 80s?”

There is a perception that black lung is a thing of the past thanks to technological innovations and increased oversight. Some miners themselves think it’s something that only affects old-timers and retirees, and assume that they’re in the clear. The unfortunate truth, according to the Appalachian Citizens’ Law Center, is that black lung is at a 25-year high. Even worse, current conditions mean that those younger workers are at risk of getting sicker faster, and of contracting progressive massive fibrosis, the most severe form of black lung.

“If you go back to my mine today, and look for a couple young guys and tell them that black lung is on the rise right now, they’d probably look at me like, ‘What do you mean? That’s an old man’s disease,’” UMWA International District 2 Vice President Chuck Knissel told me. “But I know guys that are in the mines right now that are 25, 26 years old. They go take off for a walk, and say, ‘Man, I can’t breathe. It’s hard for me to catch my breath. I don’t even smoke cigarettes, what’s going on?’ Yep, you’ve got coal dust in your lungs.”

Knissel, a gravel-voiced third-generation miner, spent 17 years working in Pennsylvania’s Cumberland coal mine before following his late father, Larry, into the union. At a convention dominated by white-haired elders, even with his salt-and-pepper beard, the 41-year-old Knissel is practically fresh-faced. Though he has not yet received an official diagnosis, he told me he’s sure he has black lung: “I have issues with breathing. A lot of my friends I’m with every day, I know they’ve got it too.”

Epidemiologists from the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) began seeing an increase in black lung cases among younger miners back in 1995. In 2017, the American Journal of Public Health published a NIOSH report documenting an uptick in black lung cases in central Appalachia since 2000, and found that 20.6 percent of long-tenured miners have the disease. A year prior, another study had found a similar situation affecting workers in Kentucky, Virginia, and West Virginia. In 2018, NPR ran a series investigating the rise in black lung cases in younger workers, raising alarm bells that were largely unheard outside of the mining community. Almost five years later, cases are still rising.

According to Secretary Williamson and the veteran coal miners and union officials I spoke to for this story, there are several reasons for the continuing spike. Appalachia’s coal seams have thinned out after centuries of extraction, and so miners have to dig deeper to reach the desired material. The machinery they use to do it, though, has improved since their fathers’ and grandfathers’ day, allowing them to massively increase the volume of rock they cut through. But this kicks up even more silica in the air. As Knissel explained, “You’re mining 30,000 tons in a 24-hour period. In the 1960s, it might’ve taken you two weeks to mine that much.”

There are existing regulations, engineering controls, and safety standards in place that mine operators are expected to follow to keep silica exposure down. Miners are also provided with safety gear to lessen their personal exposure, but, to Knissel’s frustration, not everyone uses it as often as they should, especially the younger, “tough guy” types. “We don’t have to reinvent the wheel,” he told me. “It’s just a matter of making it a part of the job every day, and not an ego thing, or thinking you’re a dork because you wear your safety glasses and respirator every day. Everybody should be the dork for not wearing them!”

Still, the onus should not be on individual workers to create a safe working environment, and while Knissel said that some mine bosses do try their best to protect their workers and keep dust to a minimum, others—as Pulitzer Prize–winning journalist Chris Hamby detailed in his 2020 book Soul Full of Coal Dust A Fight for Breath and Justice in Appalachia—are far less fastidious about following rules or adhering to safety regulations. In Knissel’s estimation, enforcement is the key to cleaning up the coal dust problem on the bosses’ end: “The only way that you’re going to get these coal companies to listen is hit them in the pocketbook.”

After the announcement, I spotted Williamson inspecting a hulking, robin’s-egg-blue MSHA Emergency Command Vehicle parked in the middle of the exhibit hall, and climbed in for a chat. As we settled into its spacious innards, he explained how his experience as both a labor lawyer and a coal miner’s grandson has always landed him on the side of the workers and how important this initiative is to him personally. “The thought, and especially from my perspective, is, what can we do now to protect miners, even though we’re going through this rule-making process that will ultimately promulgate a health standard that will be much more protective?” he explained. “That’s where this enforcement initiative comes in; that’s why it’s important. It’s what we can do now to take some proactive measures to protect minors against exposure to high levels of silica.”

The West Virginia native has been on the job for less than two months, but he’s already named silica as his top priority. As he mentioned, MSHA is also working on a new silica federal regulation, but the rule-making process is slow, and workers need help now. “We have to be strategic with it. It’s going to be another resource thing at an agency that’s already spread pretty thin on resources, but it’s worth it, because miners are getting sick,” he said. “I’ve seen so many people develop these lung diseases from working in mining environments. You can’t play with your grandchildren. You can barely walk. Eventually, you have to pack around an oxygen tank with you. That’s no way to live.”

After hearing Williamson’s initiative, Whitt was impressed by its scope, telling me that someone should’ve done it “years and years and years ago,” and was pleased to see a fellow West Virginian standing up for him and his people. “He is from where I’m from, he only lives about maybe 15 miles from where I’m from in Mingo County,” Whitt told me proudly. “I think Chris is going to do an excellent job, and he’s going to bring about some great laws.

When I caught up with Knissel at the pool, he echoed Whitt’s optimism, and said he hoped the agency will help spread the word about the black lung crisis. Knissel’s own message to young miners is an entreaty as much as it is a warning.

“We need to be a little bit smarter as coal miners and as young men, and protect yourselves,” he said. “You want to be able to enjoy the fruits of your labor. We got enough shit to worry about: We got the roof that can collapse in on us, we got motors that can smash into us. The easy stuff is wearing the things that are provided by engineers that have figured out that, hey, if you wear this, it’s going to protect you, and you’re not going to have to wear that oxygen mask when you’re 50 years old.”

Kim KellyTwitterKim Kelly is a writer and labor activist based in Philadelphia. She is the author of Fight Like Hell: The Untold History of American Labor.