“We Never Assumed Anything”: A Lifetime of Providing Abortion Care

In their new book We Choose To, Dr. Curtis Boyd and Glenna Halvorson-Boyd reflect on their decades helping women who needed abortions—before, during, and after Roe.

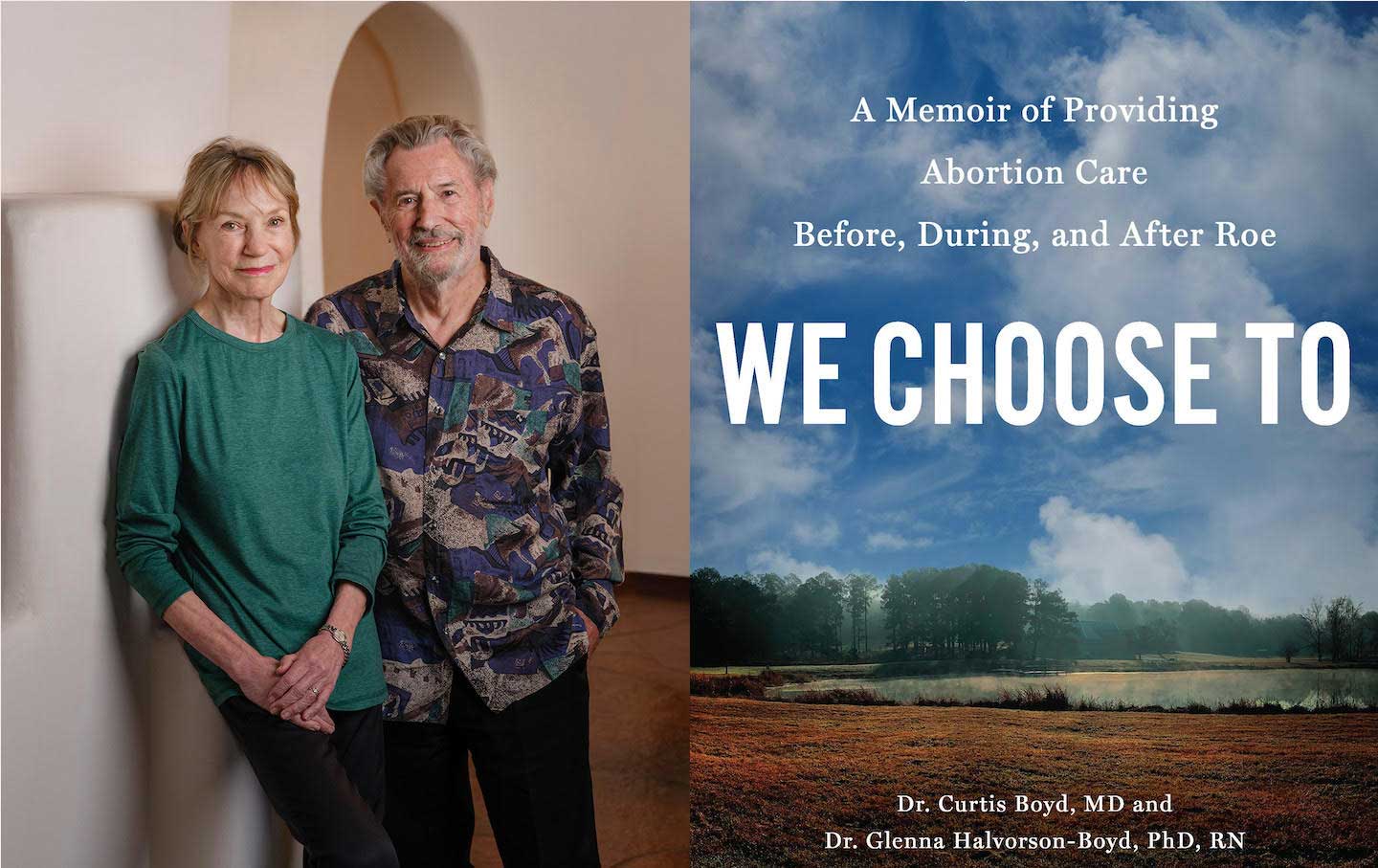

Five years ago, when Curtis Boyd, MD, and Glenna Halvorson-Boyd, PhD, RN, set out to write a book about their lives and 50-year-career providing abortion care in Texas and New Mexico, Roe was still the law of the land. But their book, which was published in September, made its debut two years after that landmark case was overturned and just a few short months before Donald J. Trump will retake the White House. As they explain in the Afterword of We Choose To: A Memoir of Providing Abortion Care Before, During, and After Roe (Disruption Books), the work they devoted their lives to, expanding access to abortions, is being undone—and once Trump is back in power, that reversal will only accelerate. We can expect that Trump will seek out ways to impose international abortion bans like the global gag rule, and his supporters would like to see him enforce the Comstock Act, which would ban mailing abortion pills. Knowing all of that, Glenna’s question in the Afterword hits hard: “Why did we bother?”

It can really start to feel that way. But as the Boyds remind us, the 2022 ruling overturning Roe isn’t the end of the story, and neither are Trump’s electoral wins. “Abortion has been with us ‘since the dawn of time.’ It will not go away,” writes Glenna.

At the same time, as new ProPublica reporting makes clear, we can expect that more people will suffer and die as access to abortion is further limited and as health care is criminalized. For that reason and many others, they feel, we have a duty to tell our stories and document history. These stories will serve as an important counterweight to the onslaught of bad news that is sure to come, while ensuring future generations can pick up the torch and light the way forward.

In early October, I spoke with Glenna and Curtis about their new book.

We Choose To chronicles how they met—Glenna started working as a counselor at the abortion clinic in Texas where Curtis was the abortion provider, one year after the Roe ruling—and built a life together, ultimately running abortion clinics in the Southwest together before retiring earlier this year after the sale of their Albuquerque, New Mexico clinic, Southwestern Women’s Options. Before Curtis met Glenna in early 1974, he provided abortions in a small town in Texas through the Clergy Consultation Service (CCS) while abortions were still illegal, and he would sometimes provide abortions beyond the “acceptable” pregnancy limit to ensure very few, if any, patients were turned away. “Seeing women through this underground network broadened my understanding of what it meant to be a woman in the 1960s and strengthened my belief that I was doing the right thing,” says Curtis. After abortion became legal, Curtis’s abortion clinic, the Fairmount Center, became the first legal clinic in Texas.

Early in her career, while working as a nursing resident at a halfway house, Glenna helped two other residents—in 1970 and 1971—to access abortion care. Glenna raised funds for their care and coordinated their travel to the Feminist Women’s Health Center (FWHC) in Los Angeles, where care was legal. So when she was looking for a new job and saw an opening at the Fairmount Center, she applied for the open counselor position and was hired by an administrator on the spot. Because abortion care was still fairly new as a field, Glenna discovered that “no one knew what abortion counseling should be—or could be” and that she would have to create her own approach. While Glenna was establishing a “psychosocial” counseling method that was rooted in treating people as they deserve to be treated—with dignity and a sense of empowerment—and benefited their patients and clinic staff alike, Curtis was pioneering a second-trimester abortion method to minimize surgical risks, the dilation and evacuation (or D&E) method. (I previously interviewed Dr. Curtis Boyd for my book with Renee Bracey Sherman, Liberating Abortion, which we also discussed in our interview.)

For all of their professional achievements, including serving as founding members of the National Abortion Federation, a professional organization for abortion providers, one of the most delightful stories in the book was how they met. During Glenna’s second week, she tried to kick a bearded, flower-vested, bellbottom-wearing Curtis out of the clinic because she was concerned his appearance was making the patients uncomfortable. He was only amused and didn’t tell her that it was his clinic; she found out later that day that the hippie rattling her patient was the doctor. But that first encounter did not get in the way of them eventually developing a strong bond, first as colleagues, creating a counseling training program together, and later as wedded partners.

Curtis and Glenna’s story—of love, of triumph, of accepting what is amid the uncertainty of our lives—serves as an important reminder of how we may not sunset our work on a win, but that is why we must learn how to face our losses, which are all but certain on the path to liberation.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

—Regina Mahone

Regina Mahone: Why was it important for you to write this book?

Glenna Halvorson-Boyd: This is one of our closing gestures in our career, and it’s a handoff to the future and to your generation. What you’re doing [with your book, Liberating Abortion] is the future we have. We’re not at all where we hoped to be at this point in our careers, but [handing it] off to young, energized, vocal, proud folks from such varied backgrounds and varied experience is what we’ve always dreamed of.

The other big thing is that we knew we wanted to change the public discourse around abortion. We were frankly sick and tired of having something that we knew—at a deeply personal level for ourselves, for our staff, for our patients—is a thoughtful, heartfelt act in a person’s life, treated as a political football. Any of us who come to this work and find it so deeply satisfying and meaningful, it touches important chords in our own lives, and we chose to make that real.

Curtis Boyd: We were tired of the old conversation—it was bitter, it was argumentative, it was violence, it was religion. We wanted to talk about women’s experiences. A woman would come to us because she was in a particular situation and she needed us to help her resolve that. We never assumed anything when she came to us, that’s what people don’t realize. We didn’t know whether she was going to have the abortion or not. Some women would come pregnant and decide not to have the abortion. Other women had thought a lot about it and felt that they would have never had an abortion; they were anti-abortion, but then they got pregnant, and they would decide to have an abortion. Sometimes they would come still undecided, but then, yes, they would have an abortion. What we’ve learned is that no one really knows what they will do until they’re actually confronted with that life situation. We live in a context: do we have a job or not, did the man who got us pregnant just desert us? All of these decisions are made within the context of your whole life. And it’s the woman’s decision.

RM: In the book, you talk about your life, your family, personal setbacks. Why did you decide to approach the book, which is about your work providing abortions before, during, and after Roe, in such a personal way?

GHB: We got so personal at the beginning of the book in part to answer a question that people pose in different ways all the time, and often the subtext of the question is definitely an insult. It is, Why in the world would anyone do this work? What kind of people would do this work? Well, there are really profound reasons. And that’s what we started with, what’s the answer to “why”?

CB: Glenna got her doctorate in psychology, [and people would ask,] Why would you want to spend your life killing babies? How could you do that? Well, that’s not what it’s about. We’re talking to patients about their lives, their dreams, their aspirations, and also doing abortions. It’s very different from other aspects of medicine. It’s a commitment to a social cause, and in particular to women’s reproductive rights and women’s equality in our society. It’s a big issue. We never saw [this work] in a narrow context.

RM: When Renee and I were doing research for our book, we read John Riddle’s books documenting ancient abortion methods, like using crocodile feces. It sounds weird today, but what I most appreciate about this example is that it is proof that people have been having and providing abortions for thousands of years. In your book, you document your work pioneering a second-trimester abortion method, the D&E method. Why was this important to you to document?

GHB: That became increasingly important to us as we were writing because of the political shift occurring in the country, and our strong sense that this hard earned, hard won knowledge can be lost. At one point, we were not sure we would have a publisher. We thought, I don’t care. If it lives only in the archives of several fine medical schools and universities, that’s enough. Like the research you [and Renee] were doing, so it’s there for the future.

CB: It might have only been there if not for Disruption Books. We went to some high-end publishers, but they wanted a different book.

GHB: They wanted the usual political book.

RM: Renee and I had a similar experience! The first couple of agents we talked to wanted a different book and we had to advocate for the book that we wanted to write.

You also talk in the book about why the hospital setting is often not the ideal setting for abortion care. But of course, we’re seeing laws that require providers to offer care in ambulatory surgical centers. Can you talk about why this thinking is so wrong?

GHB: There are some abortions procedures that need to be done in the hospital, just as there are lots of medical procedures that need to be done in the hospital. But early abortion, uncomplicated [procedures] can be safely done in an office setting. There, you select staff partly for their natural warmth and their concern for humans as well as their medical training [and] their counseling training. In the 1980s, I did training for staff at a hospital with a huge labor and delivery floor—and to their credit, they were doing abortions now that they were legal. So I naively show up in this big amphitheater to lecture about 60 doctors and nurses, and the vast majority of those nurses were rabidly anti-abortion. The questions that they asked me, or the comments that they made to me, were so disparaging of the patients they were there to care for. I walked away thinking, this is not where I would want to go for care. So the ability to make the care patient-centered and sensitive to the right issues that come up with a pregnancy that’s not going to work out creates the best possible setting to have that experience.

I mean, you talked about [in Liberating Abortion] having to wait forever.

RM: Yeah!

GHB: Most medicine—and frankly it happens with us too—you know, you wait so long and the waiting time is often the hardest part. It’s anxiety producing, wondering what’s about to happen. It’s what you’re there for, but it’s all real, happening right there.

RM: Yeah, it really does help to have a warm and soothing environment when going through any medical experience. But for too many patients today, we’re only in as much control as the medical system allows us to be, and as much as the laws allow us to be. How would you comfort a patient in this environment?

GHB: In a state where your work is legal and you’ve got the community support that you need, then you can provide fine, humane care. It’s working in a state where you’re not supposed to even give accurate, factual information, or it could be a felony—there is no comfort to be given there. Fortunately, there are some religious organizations, some churches, just as there were before abortion was legal under Roe, that are under the umbrella of the church and the confidentiality of that relationship, are able to provide sensitive care and accurate information and referral to the many good providers who are working very hard to meet the need.

CB: It’s an impossible situation and you just have to make the best [of it] that you can. In these states, there are a lot of organizations that are referring women to [get their abortions]. They will give information, and they will help to make arrangements to get you out of state. But that costs a lot of money—it’s roundtrip airfare, you got to be off work, you may [need] childcare, and even if [child care] is covered [the organizations cannot] pay for your lost wages. We’ve had [these patients] coming to us. We gave them a free abortion, we gave them their medicine, we gave them food while they were there. But what’s hard, and it’s unspoken, is it’s very anxiety provoking to have to get on a bus or plane and have to go to another state [for a procedure]… It feels like what you’re doing is illegal. You don’t know where you are going and you feel even less in control. It’s a terrible situation. Some of these referral programs are very good. But the women want to have their abortions back home.

RM: In 1990, providers were concerned about “the graying of abortion care” and you two presented at a symposium on the challenges in recruiting younger doctors. Today, we are seeing providers leave ban states. What do you see as the biggest challenge facing abortion providers today? And what advice would you offer providers navigating this landscape?

GHB: What I would say is the good news is that there’s a large number of young physicians—they’re primarily women—who are absolutely dedicated to providing the care. The graying of care is no longer an issue. There are wonderful young providers absolutely determined, and they are courageous people choosing now to go into the field, because they see how desperately needed abortion is. The upside of this situation is that it’s brought to the forefront of people’s mind how important this is. People are, as we were in the 60s and 70s, saying, What can I do to remedy this social evil? And they’re stepping up to do it, and that gives me great hope for the future.

CB: There’s no shortage of abortion providers, but they’re all in cities. If you don’t live in a city, then you’re going to have to travel to a city to get service. Why is that? Let me tell you some of the reasons.

If you [are an abortion provider and] go to smaller [communities], [your work is] controversial. If you go to join a medical practice, they may not want to take you in if you want to do abortions. They may not be opposed to abortion, but they don’t want problems. They don’t want the harassment. They don’t want to lose their practice. They don’t want to be known as abortion providers. If you try to go out on your own in these towns, sometimes you cannot either buy or rent property if they know you’re going to provide abortions. But even if you manage to buy, there are other limiting factors. People think, Oh there will be a lot of abortions. But really there would be very few. If a primary care doctor did one a week [in these towns] that would be a lot. And you know if you want insurance for providing abortions, it’s expensive. If you do just one abortion a year, you’re providing abortion services, and you have to get OB-GYN insurance. Primary care insurance may be very inexpensive. Let’s say it’s $25,000-$50,000 a year. For an OB-GYN, it’s going to be $150,000 a year. So you’re paying $100,000 more. Just calculate how many abortions you got to do just to pay the difference in the insurance premium. You might do two a week and that’d be big. It becomes financially impossible. I could keep going.

RM: Yeah, and the Medicaid reimbursement rates make it so expensive, because they are so low.

CB: Too low, especially in the second trimester and advanced stages. When we did it at advanced stages, it turns into major surgery; it can take three days [and there are other staff costs associated with the higher risk for hospitalizations]. You got to pay a doctor to be around, pay staff to be on call—the support staff 24/7—it’s a lot. There are all of these issues, and Medicaid will not reimburse for all of that. It’s very little. So we’ve got a lot of structural issues to solve.

The Ryan Residency Training program [is one way we started to solve some of these issues]. The program was in one medical school and is now in 100 medical schools; it [facilitates] training so doctors come out prepared to provide reproductive health care services. [So] those doctors exist now. But they have to go to the city because small towns [don’t provide this training]. Then [Glenna has pioneered psychosocial] workshops, teaching about community, how to provide caring services for the patient, and also how to [practice] self-care, because these doctors, they have problems too. I mean, did they have family objections? Is this “murder”? Well, that’s psychosocial. I mean, this is dealing with psychological issues, not medical, but medicine needs to deal with that—all of medicine, every doctor should be taught psychosocial. It should be just like at every high school they should be required to take civics courses, and courses about logic and reason.

RM: This brings us to the final chapter of the book. In it, you discuss the importance of religion for patients, religious traditions as well as cultural rituals or ceremonies, such as setting out an altar to memorialize someone or an experience, like an abortion. Why was it important to acknowledge the way that abortion can create inner conflict within people—patients, staff, and providers—and the different ways people address that head on?

GHB: For many patients, many people who are pregnant, many people who provide abortion, there isn’t conflict. For many, there is an inner tension and [it can help to create] a safe space, whether to talk about it or whether to enact a ritual or a ceremony—that [practice] varies tremendously from person to person. We wanted to create a safe space that recognizes that for many people, there is some level of tension or discomfort, which I find to be true in most major life decisions. Those of us who are thoughtful [and don’t just see things in] black or white—there’s a lot of gray in there. Having a safe space to express some of that gray with someone who understands and cares is of tremendous value.