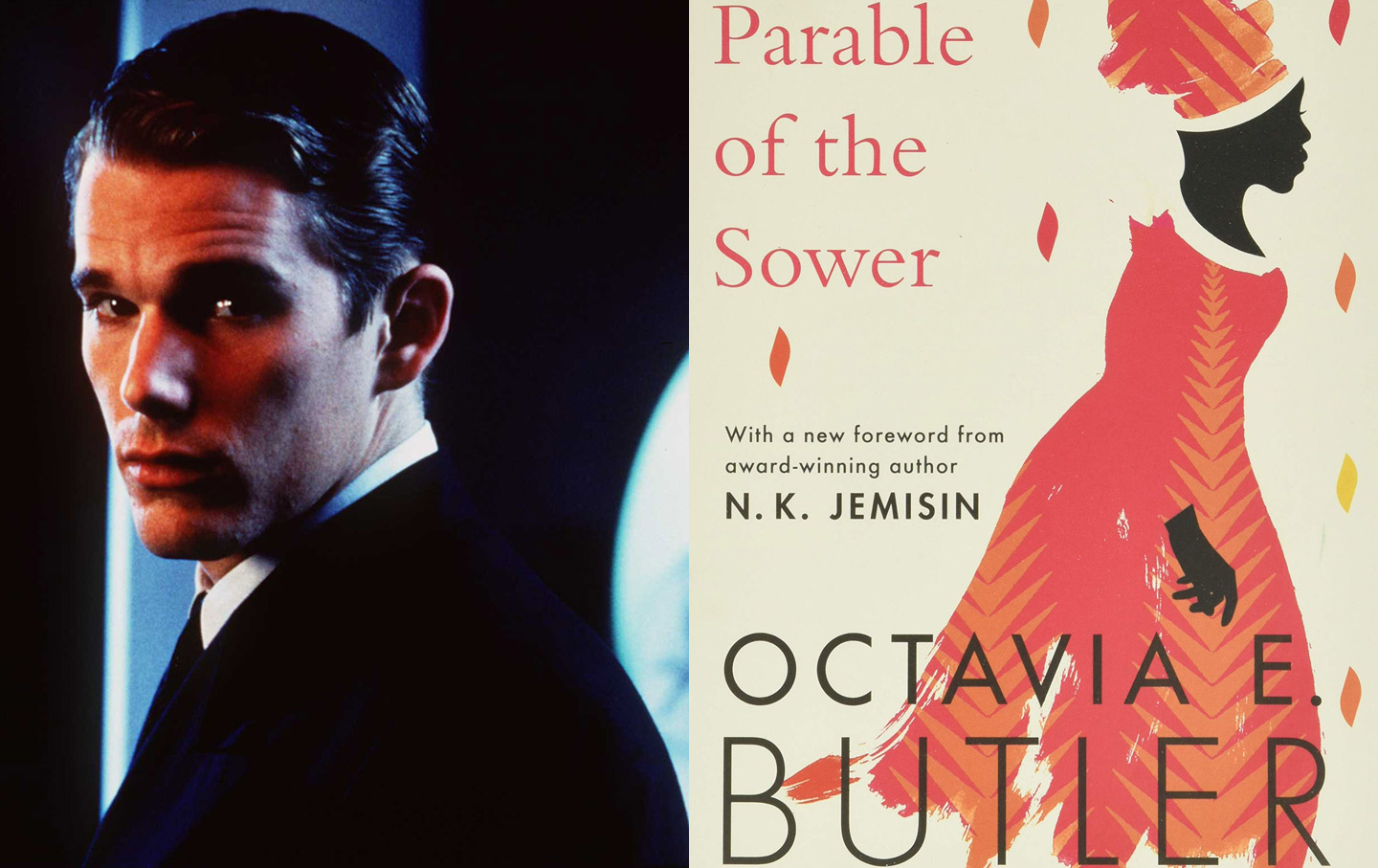

Ethan Hawke in Gattaca, left, and the cover of Octavia Butler’s Parable of the Sower, right.(Getty Images)

A little less than halfway through the 1997 film Gattaca, Irene (Uma Thurman) steals a strand of hair from the desk of a coworker she knows as Jerome (Ethan Hawke), and takes it to an all-night DNA testing booth, passing a woman who is having her lips swabbed just five minutes after kissing her date. A few seconds later, the technician gives Irene her answer: “Nine-point-three—quite a catch.” But 9.3 of what? How does her printout of amino acids translate to a scale of 1 to 10, a “genetic quotient” that leads the technician to think her boyfriend is a catch?

After nearly a quarter century, Gattaca has aged disturbingly well. The New Zealand writer and director Andrew Niccol crafted a noir dystopian thriller of a society trapped by eugenic ideology and ubiquitous biometric surveillance. Those with poor GQ are deemed “in-valid” and condemned to a life of poverty, drudgery, and crime. But those with good GQ also measure themselves against impossible standards, believing that their DNA determines what they should be able to do, and they plunge into depression, suicidality, and self-sabotage when they’re unable to meet expectations. Today, as we charge into an age of biotechnology, the film feels especially prescient, providing a benchmark against which to compare our trajectory. Our capacity for both genetic manipulation and biometric assessment is advancing, but we have not improved our ability to hold conversations about genetics, disability, or even abstractions like the relationship between probability and outcomes. I worry that our Gattaca future is nigh.

The hair fiber may have scored a 9.3 GQ, but it doesn’t come from Hawke’s character, whose real name is Vincent. Vincent is an invalid, a child conceived in the back seat of a Buick and allowed to develop as nature sees fit. He’s got a 99 percent chance of developing a heart condition, and his life expectancy is 30 years. He’s also brilliant and wants to be an astronaut, but he has no chance of passing the genetic screening for a space gig at the Gattaca Aerospace Corporation. So he engages in a criminal conspiracy with the real Jerome (Jude Law). Jerome was genetically engineered to near perfection, becoming a champion swimmer and a silver medalist in the Olympics before suffering a spinal injury in a car crash. (Later we find out that Jerome, unable to tolerate being second best, had stepped in front of the car. It’s the rare disability-suicide plot point that places the blame on society rather than on disability.) Jerome makes a deal to provide Vincent with hair, blood, urine, and skin samples in exchange for a portion of Vincent’s salary. The fraud works. Vincent becomes a navigator, but before he can launch into space, the mission director at Gattaca is murdered. A manhunt ensues, the cops find an eyelash from Vincent himself, and the movie rolls forward.

It’s a pretty good plot. Vincent has a genetically engineered younger brother, Anton, against whom the naturally conceived in-valid measures himself, a tension that plays out in adulthood. Vincent helps Irene realize that even if she’s not perfect according to the charts (she’s “valid,” but no 9.3), she can do more than she realizes. But it’s not the plot that’s made the story endure; rather, it’s the film’s vision of the world.

The premises of Gattaca feel real not just because its characters espouse long-held eugenic principles in the development of prenatal testing and genetic engineering technologies but because the movie pairs those ideologies with surveillance. It’s one thing to have an ableist viewpoint about the value of people, another to have the technology for genetic engineering, and yet a third to build a society around the routine penetration of the body to extract blood, urine, and saliva and measure it against a universal database.

The film isn’t perfect. Aside from the presence of a Black geneticist and a few extras, its world is extremely white, and I don’t think that’s an accident. As we watch Vincent embark on his early career as a janitor, he provides narration about the times, saying, “I belong to a new underclass, no longer determined by social status or the color of your skin. No, we now have discrimination down to a science.” That’s nonsense. Ableism and eugenics intersect with racism, classism, and other forms of discrimination. Inventing new forms of discrimination does not erase the old ones.

Still, a single film, like a single essay, doesn’t have to do everything. Make no mistake, our Gattaca future is coming; the technology can’t be held back. What we must do now is work to undermine the eugenicist ideologies that will lead those technologies to cause increasingly greater harm. And that’s where this movie comes in. When I talk to people about designing babies, I often get assurances that discrimination against kids like mine—my son has Down syndrome and is autistic—is bad, but where’s the problem in trying to create advantages, to alleviate burdens? Gattaca, however, makes the case that you cannot design your way to happiness and that trying to do so will build a world ever less free—even for those who achieve high marks in GQ, IQ, or whatever other rubric we use to mismeasure potential.

David M. Perry

The events in Octavia E. Butler’s 1993 novel Parable of the Sower presage this moment of mass shootings, global warming, en masse migration from California, a pandemic that throws into relief rampant structural inequities, widespread drug abuse, and a presidential candidate who campaigned on returning the country to a sense of so-called normalcy. (In the book’s sequel, 1998’s Parable of the Talents, one politician promises to “Make America Great Again.”) When the novel was published, it was set 31 years in the future. The gap between the version of life Butler imagined and the one we’re living in is closing.

Parable of the Sower tells the story of activist Lauren Oya Olamina, who is 15 when the book begins and lives in an increasingly destabilized Southern California with her minister father, her stepmother, and her four brothers. Like other micro-communities in their Los Angeles County town, the Olaminas and a handful of other families live behind a wall to escape looting, murder, sexual assault, drug abuse, arson, and corporate slavery. Responding to her environment, Lauren has already started to develop Earthseed, the spiritual philosophy she creates based on the notion that “God is change.” She lives with a condition called hyperempathy, which causes her to become ill when she vicariously experiences the suffering of others. It is perhaps this hyperempathy that makes Lauren so attuned to the impending doom around the corner (literally, for her and her compound). She seems to be the most worried person in her community and suggests that people refine their emergency preparedness for a series of catastrophic events. She reads history books to fortify herself; in a conversation with a friend, Lauren underscores the significance of the Black Death in the 14th century, saying, “It took a plague to make some of the people realize that things could change.” Eventually her suspicions come true, and Lauren leads a band of travelers to Northern California in search of freedom, paying jobs, and affordable water.

In a present-day America that’s reeling from the toll of the pandemic, the War on Drugs, the prison-industrial complex, reproductive oppression, and weakened labor unions and that is constantly threatened by white supremacy, the cowardice of career politicians, and the avarice of the wealthy, the lessons of Parable of the Sower have practical application. The principles of Martine and Bina Aspen Rothblatt’s Terasem Movement (founded in 2002), which focuses on nanotechnology and cyber-consciousness, were inspired by the book’s Earthseed philosophy. adrienne maree brown’s 2017 manual Emergent Strategy: Shaping Change, Changing Worlds was also influenced by Earthseed. Since last spring, Tananarive Due and Monica Coleman have hosted a series of webinars called “Octavia Tried to Tell Us: Parable for Today’s Pandemic,” in which Butler scholars explore the context and imaginative implications of the book’s predictions. In an October 2020 interview in The Believer, writer and housing attorney Rasheedah Phillips advised people interested in envisioning survival to start with Butler. “She is the person who prepared me, to the extent that I am prepared for this,” Phillips said.

Yet it is not only because of its pragmatism that Parable of the Sower should be considered the more prescient dystopia; it also ingeniously foresaw movements in today’s culture to recenter marginalized groups, including young Black girls and women; Indigenous communities, whose botanical and nutritional insights are crucial to the survival of Lauren and her band; and youth, of which the Earthseed collective is mainly composed. Lauren is a fictional forerunner to courageous young people like Darnella Frazier, X González, Greta Thunberg, and the late Erica Garner.

Perhaps the biggest indication of Parable of the Sower’s foresight is its understanding that as powerful as empathy is, it’s not enough (Namwali Serpell’s New York Review of Books essay “The Banality of Empathy” is also useful in articulating this idea). When Lauren’s lover suggests that it might benefit society if most people had her hyperempathy, Lauren calls the notion a “bad idea.” “You must know how disabling real pain can be,” she insists. Just as hyperempathy is not enough to save Lauren, it won’t be enough to save us. Empathy takes courage, compassion, and an interest in alterity, and many people in her world and ours lack those qualities. But art, at least, can prompt us to think critically. Like empathy, critical thinking requires compassion and a desire to move past pretense toward truth.

Here again, Parable of the Sower is telling. “Use your imagination,” Lauren tells a friend. “Any kind of survival information from encyclopedias, biographies, anything that helps you learn to live off the land and defend ourselves. Even some fiction might be useful.” And the novel has been. But as Lauren learns, reading is only the first step. Explaining her impetus to move beyond studying, Lauren tells someone from her old neighborhood, “I thought something would happen someday. I didn’t know how bad it would be or when it would come. But everything was getting worse: the climate, the economy, crime, drugs, you know.” Yeah, I do know—and all of that requires thoughtful action now.

Niela Orr

David M. PerryTwitterDavid M. Perry is a journalist and historian. He is a coauthor of The Bright Ages: A New History of Medieval Europe. His website is davidmperry.com.

Niela OrrNiela Orr is a deputy editor of The Believer and a fellow at the Black Mountain Institute.