Deion Sanders and the Joys of Hype

While other college football coaches pine for the past, Deion Sanders has taken advantage of new rules and made the present fun.

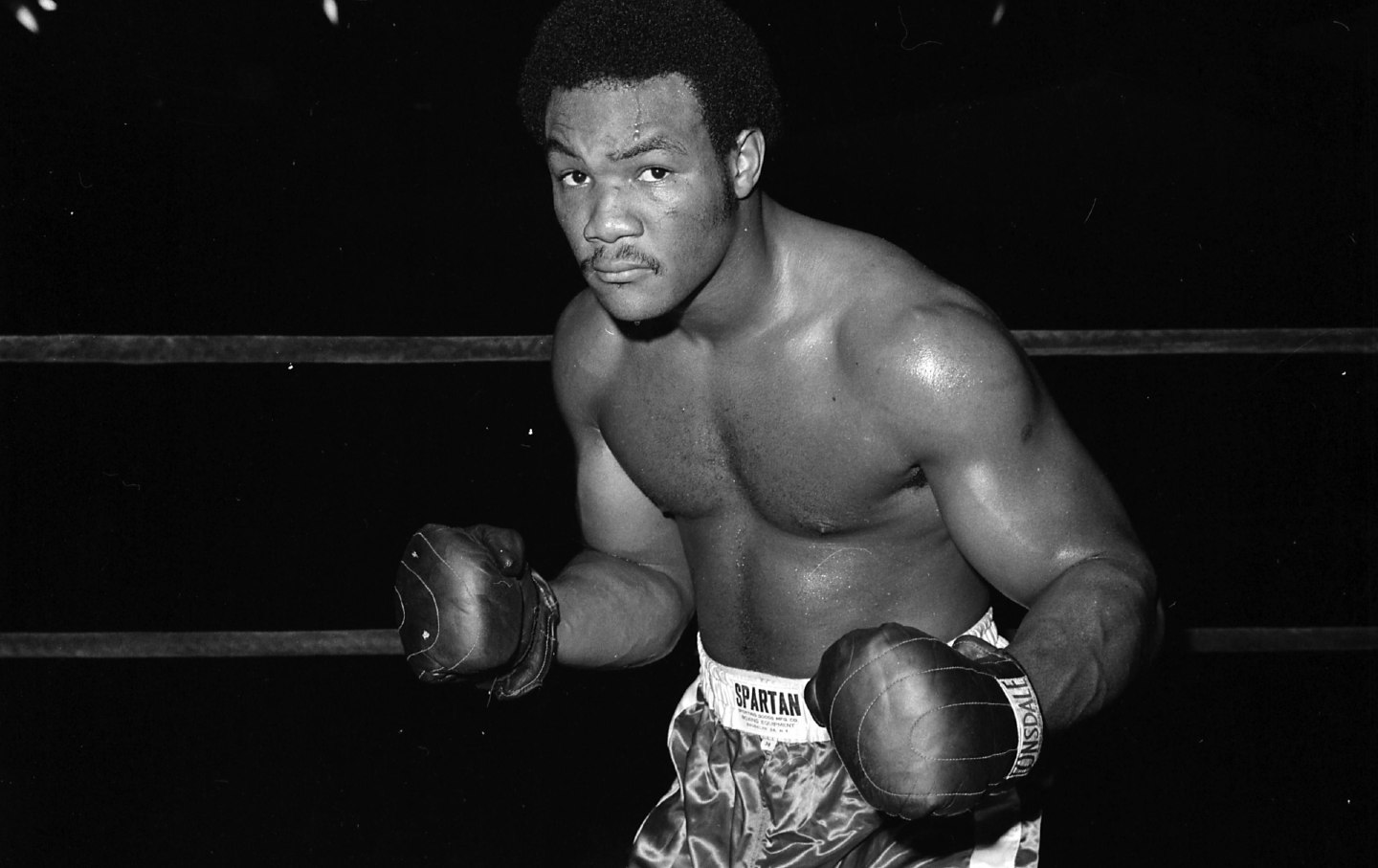

Colorado head coach Deion Sanders, right, hugs his son Shilo Sanders during an NCAA college football game against Colorado State on September 16, 2023, in Boulder, Colo.

(David Zalubowski /AP)On Sunday night, 60 Minutes, the grandfather of television news shows, was hyping two interviews. The first was an exclusive conversation with Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky about fighting back Russia’s invasion. The second, announced just as breathlessly, was another exclusive. This one was with a head football coach in a Colorado college town—a town perhaps best known for snowboarding and whose team last year went 1-11. That coach is, of course, the NFL Hall of Famer Deion “Prime Time” Sanders.

The publicity and curiosity that Sanders has generated after just two games at the helm at the University of Colorado–Boulder speaks to the team’s turnaround, not just athletically but culturally too. A year ago, the squad was ranked 128th out of 131 teams, and it had been bad for years. Then, from historically Black university Jackson State, came Coach Prime, bringing with him his two preternaturally gifted sons, Shedeur and Shilo. He ruthlessly remade the operation, engineering a roster turnover with little regard for anything other than reimagining a woebegone program. While many other coaches whinged tiresomely about the new rules that govern college football—like players having access to “name, image, and likeness” money or being able to rapidly transfer from one school to another—Sanders has taken advantage of them. While others pine for the past, Coach Prime has decided that the present is a fine and even a fun place to be. Instead of sneering at it all and begging their old buddy, the openly racist Auburn coach turned seditionist Senator Tommy Tuberville, to step in legislatively, Sanders has brought something absent from college football: the joys of hype and the hype that comes with joy.

Sanders’s haters are legion. Yet the hate is not because of his sunglasses or his hat or his attitude or whatever other dog whistles various coaches and commentators are throwing in his direction. The root cause of the hate is that he has stepped into this world from a TV desk and is doing it not just differently but better—and that drives the minders of the game into fits. For decades, college football coaching has been a mausoleum of elderly, square, overwhelmingly white coaches working out their issues on teenagers by barking at them as if they are about to fight the Battle of the Bulge. The only requirement for this job has seemed to be the ability to pair ulcers with high blood pressure. Sanders has smashed the stained glass windows, and let in some oxygen to this world.

It’s a culture shift that will eventually drag the sport into the present and out of its revanchist past. As longtime Colorado hip-hop community radio host Dave Ashton told me, “It’s 2023, and 50 years after hip hop’s birth, hip-hop attitude and culture finally is a part of the world of college coaching.”

The presence of hip hop as a cultural force in college football is alive in, of all places, Boulder, Colo., and playing out in front of a crowd of mostly white students. It’s not just the presence of Lil Wayne and Offset, who helicoptered into Boulder to be on the sidelines of Saturday night’s game against Colorado State. It’s not just that his son, quarterback Shedeur, wears a gold chain thick enough to use on your tires during a snowstorm. It’s making these games feel young and alive instead of stultifying and grim. Saturday’s Colorado–Colorado State game was emblematic of the colliding of these worlds. Colorado State coach Jay Norvell attempted, to the thrill of college football’s right-wing commentariat, to turn the game into the State Farm Respectability Politics Bowl, counterposing himself with Sanders. Norvell, who is one of the few Black coaches in college football, said to Sports Illustrated the Wednesday before the game,

“I don’t care if they hear it in Boulder. I told them, I took my hat off, and I took my glasses off. I said when I talk to grown-ups, I take my hat off and my glasses off. That’s what my mother taught me.”

It was a statement that juiced up every “old school” commentator from the right-wing toilet that is now Twitter—officially X—to members of ESPN’s College Football Gameday.

Then Norvell showed us the morality of what “old school” looks like on the football field: targeting opponents, playing ugly, and committing 17 penalties in 187 yards. Yes, they kept it close and should have had the upset victory, instead of losing 43-35 in double OT, especially after violently knocking Colorado’s best player, Travis Hunter, out of the game. If that’s what old school looks like, bring on the new.

This is not to say that there are no critiques to be made of how Sanders has operated since becoming a college coach. His taking the position at Jackson State ostensibly because, as he put it in early statements, “God called collect” and told him to go to a historically black college, only to leave Jackson State as soon as the Colorado job became open, is not exactly a feel-good story. That being said, it is college football that’s dirty, not Sanders. It’s an amoral game whose immorality has been called out since the days of W.E.B. Du Bois and Upton Sinclair. Sometimes clichéd counsel is right: Don’t hate the player, hate the game. Don’t hate Deion because he understands the college football landscape, and, like in his playing days, has left his competition trying fruitlessly to catch up.

Hold the powerful to account by supporting The Nation

The chaos and cruelty of the Trump administration reaches new lows each week.

Trump’s catastrophic “Liberation Day” has wreaked havoc on the world economy and set up yet another constitutional crisis at home. Plainclothes officers continue to abduct university students off the streets. So-called “enemy aliens” are flown abroad to a mega prison against the orders of the courts. And Signalgate promises to be the first of many incompetence scandals that expose the brutal violence at the core of the American empire.

At a time when elite universities, powerful law firms, and influential media outlets are capitulating to Trump’s intimidation, The Nation is more determined than ever before to hold the powerful to account.

In just the last month, we’ve published reporting on how Trump outsources his mass deportation agenda to other countries, exposed the administration’s appeal to obscure laws to carry out its repressive agenda, and amplified the voices of brave student activists targeted by universities.

We also continue to tell the stories of those who fight back against Trump and Musk, whether on the streets in growing protest movements, in town halls across the country, or in critical state elections—like Wisconsin’s recent state Supreme Court race—that provide a model for resisting Trumpism and prove that Musk can’t buy our democracy.

This is the journalism that matters in 2025. But we can’t do this without you. As a reader-supported publication, we rely on the support of generous donors. Please, help make our essential independent journalism possible with a donation today.

In solidarity,

The Editors

The Nation