The Democrats Are Finally Running a Teacher. What Took Them So Long?

After decades of serving as a punching bag for the party’s neoliberals, public schools and the people who work in them are back in fashion.

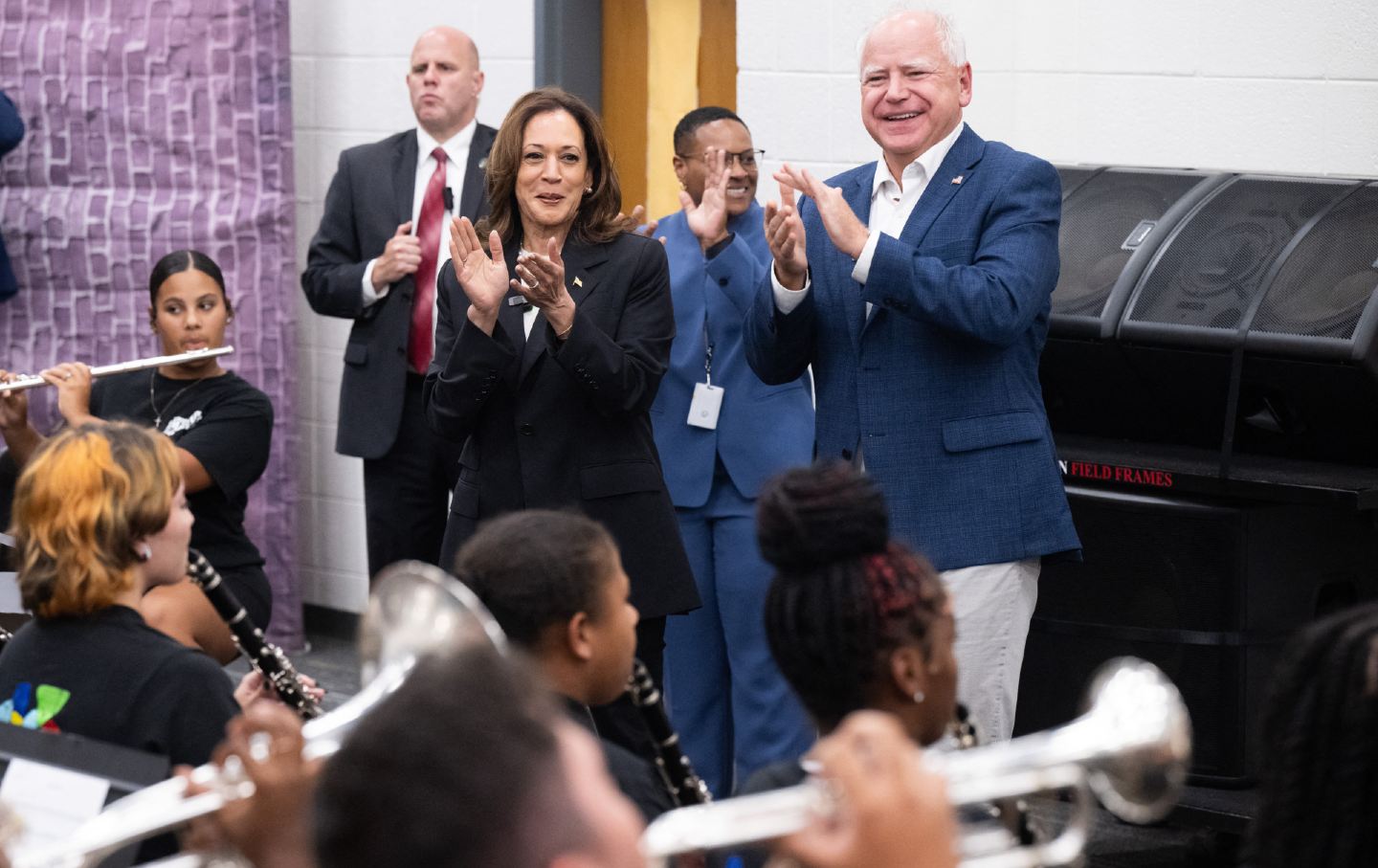

“Never underestimate a public school teacher,” Tim Walz instructed the crowd at the Democratic National Convention last month. Their raucous response to the line is indicative of Walz’s strength as a teacher turned candidate. According to one recent poll, he’s the most popular member of either presidential ticket—in part because of his teaching background.

This raises an obvious question: Why has it taken so long for the Democrats to run a teacher? After all, it’s been 40 years since Walter Mondale tapped Geraldine Ferraro, who briefly taught in the New York City schools before training as a lawyer. If elected, Walz, a former high school social studies and geography teacher, will be the first educator to serve since Lyndon Johnson in 1965.

To understand why Democrats have been so reluctant to run teachers requires a trip back into the party’s history. In the 1970s, Democrats were in the throes of an identity crisis over what they stood for—and whom to blame for their electoral setbacks. For the better part of four decades, the party had been defined by the New Deal, which made it a dominant force in American politics. “The simple but powerful idea of the Democrats’ New Deal order,” observed historian Gary Gerstle, “was that a strong interventionist state was necessary to regulate capitalism.” In practice, that meant redistributing wealth via progressive taxation, growing the welfare state to provide a safety net for those left behind by the capitalist economy, supporting organized labor, and expanding educational opportunity.

By the late 1960s, however, the New Deal order had begun to deteriorate. Decades of postwar prosperity were replaced by uneven economic growth and high inflation, which the Republican Party seized on. Embracing the dynamism of free markets, the GOP offered a distinctly different vision of the good life—one built around individuals and their buying power. Between 1969 and 1993, Democrats held the White House for just a single term. The New Deal was dead, replaced by a new political order: neoliberalism.

The neoliberal order was particularly bad for teachers. Public education is one of the nation’s most costly annual projects, and suddenly both parties seemed to agree that taxes were too high. In the era of free markets, unions were out of vogue—and government employees became political punching bags; for most public school teachers, that meant a double stigma. And while educators continued to voice support for more federal programs to meet student needs, leaders in Washington increasingly agreed with Bill Clinton that “the era of big government [was] over.”

On top of all this, teachers were also becoming more politically active. In 1975 alone, teachers walked off the job in New York City, Chicago, Boston, and several other cities. Their lengthy and often bitter strikes played out against a backdrop of fiscal crisis. And for a growing segment within the Democratic Party, the specter of teachers demanding higher pay and better working conditions—even as the communities that employed them struggled to keep the lights on—was a sign that the New Deal model was exhausted.

By the 1980s, a new breed of Democrat was running for office, and taking a stand against teachers. In Arkansas, Governor Clinton made criticizing the state’s teachers a central plank of what strategist Dick Morris called his “permanent campaign.” It made little difference that Clinton’s push for teacher competency exams was fiercely opposed by civil rights groups, who feared that the tests would disproportionately affect Black educators. Clinton, and the party he would reshape, had found a convenient political foil. When President George H.W. Bush gathered the nation’s governors together in Charlottesville, Virginia, for his 1989 “education summit,” Clinton cochaired the committee that introduced the idea of annual standardized testing. As his committee put it, the nation needed “clear lines of accountability and authority.”

Our contemporary era of teacher bashing reached its peak during Barack Obama’s presidency. The ineffective teacher—more concerned with her salary and pension than with the children in her care—became a stock villain. The 2012 Democratic National Convention, for instance, featured a special showing of the blockbuster pro-charter documentary Waiting for Superman, which excoriated the nation’s teachers, effectively accusing them of causing poverty. The showing, attended by an all-star list of Democratic Party luminaries, was hosted by Michelle Rhee, the controversial Washington, DC, schools chief who had previously appeared on the cover of Time wielding a broom.

Why would that Democratic Party run someone who is so in need of fixing—or firing?

Today, trashing teachers has fallen out of favor. Support for unions continues to rise, and government programs that support kids—programs like universal school lunch or the child tax credit—are wildly popular. At a time of rising public sentiment in favor of economic redistribution and more government support for families, teachers—who consistently make the case for both—are obvious ambassadors.

Democrats also think that Tim Walz can help them lure back some of the working-class voters the party has been hemorrhaging for years now. And they may be right. Last year, the Center for Working-Class Politics released a report on how progressive candidates can win back Americans without college degrees. Testing different types of hypothetical candidates with voters, the group found that the candidate who attracted the most support was a middle school teacher. Lawyers, who have dominated the Democratic ticket for the past four decades, ranked at the very bottom.

For the past several years, Republicans have directed increasingly harsh rhetoric at teachers, accusing them of indoctrinating kids and worse. “Government schools,” they sneeringly argue, are a vestige of the past. But there’s another story about educators and schools that we used to tell, and which we might tell again. Teachers are the people we count on to raise children’s expectations, and our public schools are how we put government to work in service of the common good. Tim Walz has struck a chord with the American public because after half a century of faith in markets, neoliberalism may have run its course. Who better than a social studies teacher to remind us what Democrats used to stand for?

More from The Nation

A Civil Rights Veteran Revisits the Summer of 1965 A Civil Rights Veteran Revisits the Summer of 1965

The white college student supported Black voters in segregated Alabama, and began documenting the front lines of the voting rights fight, which locals continue to disregard.

Notes on Transsexual Surgery Notes on Transsexual Surgery

An abundance of plastic surgery is not a net good. But discussions over its morality would be better off viewing it less as unfettered desire and more as self-determination.

I Led the FDNY. Don’t Believe Elon Musk’s Nonsense About It. I Led the FDNY. Don’t Believe Elon Musk’s Nonsense About It.

Musk’s attack on the new FDNY commissioner proves he knows nothing about how modern fire departments work.

What Black Youth Need to Feel Safe What Black Youth Need to Feel Safe

Young people are facing a mental health crisis. This group of Cincinnati teens thinks they know how to solve it.

Trump’s Death Eaters Are Coming for Our Kids Trump’s Death Eaters Are Coming for Our Kids

After taking countless lives around the world, RFK Jr. and his ghoulish compatriots want American children to suffer too.

The Supreme Court Just Held an Anti-Trans Hatefest The Supreme Court Just Held an Anti-Trans Hatefest

The court’s hearing on state bans on trans athletes in women’s sports was not a serious legal exercise. It was bigotry masquerading as law.