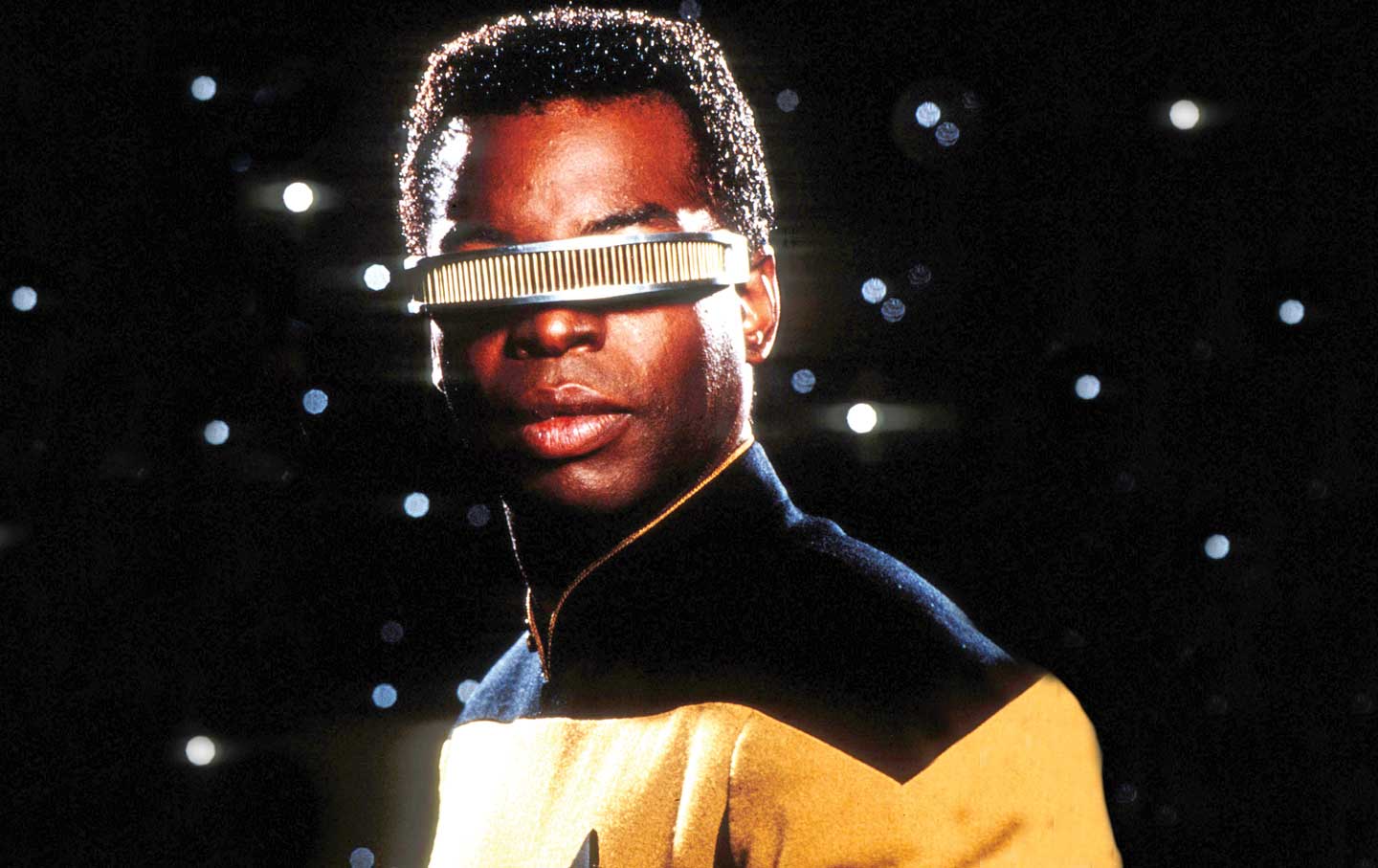

In the TV series Star Trek: The Next Generation, Starfleet officer Geordi La Forge is blind—but his VISOR (Visual Instrument and Sensory Organ Replacement) and later ocular implants negate his disability.(Alamy)

Imagining better worlds can help us improve our own, but literary and cinematic utopias often exclude those who don’t fit into what are usually racially and culturally homogeneous societies. And whether it’s 1516 or 2016, utopian thinkers are especially prone to leaving out one group whose experiences and insights should enrich our dreams of the future: the disability community.

For centuries, utopias have presented disability as a personal shortcoming to be remedied, not as an identity to be supported and celebrated. A disability in a utopia is socially undesirable—a cause of suffering that does not belong in a place where wholeness of body and spirit is prized. The disability community, however, has a very different view of itself. And understanding what a more inclusive utopia entails shouldn’t just inform attitudes about what constitutes an ideal society; it should shape the way communities approach disability in the real world.

The exclusion of disability from utopias reflects long-standing social attitudes. Throughout much of Western history, disabled people were sequestered, either in institutions or at home. Disability wasn’t a topic of discussion in polite society, except in the context of charitable activities. When characters with a disability or an illness do appear in utopian worlds, as in Thomas More’s Utopia (1516), they serve as plot devices that help develop the nondisabled characters around them. More’s denizens find pleasure and fulfillment in caring for the sick, of whom we learn nothing. Rarely, as in a text like Sarah Scott’s A Description of Millenium Hall and the Country Adjacent (1762), the authors deal directly with disability and its policy implications. Scott proposes that disabled people should be treated with dignity and respect, not exploited and housed in workhouses, a sentiment that is unfortunately still radical.

The mere nonexistence of disabled people wasn’t enough for writers like H.G. Wells and Edward Bellamy; for them, that absence was a desirable consequence of eugenics, a movement they enthusiastically supported. Bellamy’s Looking Backward (1888) positioned crime as an illness, at one point stating that “all cases of atavism are treated in the hospitals,” reflecting the belief that genetics determined criminality. Wells revisited eugenic and utopian themes over and over in his work, writing in 1901 that society should “check the procreation of base and servile types, of fear-driven and cowardly souls, of all that is mean and ugly and bestial.” He also noted that people with impairments and mental illnesses should be killed or not permitted to “propagate.” Many feminists of the era were also proponents: Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s Herland (1915) envisioned a harmonious society without men, where eugenics could hone the women of Herland to perfection.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, utopian fiction advertised the idea that it was possible to mold better people through the judicious application of breeding, sterilization, and euthanasia. Popularized by texts like Wells’s The Time Machine (1895), which imagined humans evolving into a twisted and vile race called the Morlocks, eugenics took hold in England and the United States. But the ideas didn’t stay there. American works on eugenics influenced the Nazis, who deployed utopian thinking with tragic consequences.

The visible man: H.G. Wells popularized eugenics in his utopian-themed science fiction books.(Historical Picture Archive / Corbis via Getty Images)

Utopian erasure of disability takes many forms beyond crude eugenics. In Star Trek: The Next Generation, Starfleet officer Geordi La Forge is blind—but his VISOR (an acronym for Visual Instrument and Sensory Organ Replacement) and later ocular implants negate his disability. He, in fact, has better vision than his sighted colleagues. Even then, La Forge is one of the few disabled characters in the franchise, a reminder that in this longed-for future, disability is no longer a problem, whether genetic, the result of an accident, or the cost of war. That’s seen to striking effect with Captain Christopher Pike, who first appears in the Star Trek universe as a wheelchair user but, in a forthcoming spin-off that begins before he is injured, is able-bodied. Star Trek has had diverse casts, but it has largely failed to include disability within that diversity.

Science fiction also raises the prospect of using technologies like CRISPR to edit the human genome and thereby eliminate genetic disabilities. The dystopian film Gattaca (1997)—whose name is derived from the four nucleotide bases of DNA: guanine, adenine, thymine, and cytosine—illustrates the dangers of humanity’s hunger for genetic engineering. The film is set in a society with widespread prenatal gene editing, but Vincent Freeman (Ethan Hawke) was conceived naturally and faces discrimination. As an “in-valid,” he chases his dream of going to the stars. Gattaca asks the viewer to consider the costs of a eugenic utopia, challenging rhetoric about the promise of genetic modification by taking it to a logical extreme.

The world of Gattaca isn’t necessarily far off. Some advocates fear genetic testing and editing may make Down syndrome, dwarfism, autism (which hasn’t been decisively linked to any specific genes), and numerous other impairments and identities things of the past. In a sense, the goal of some nondisabled-led disability organizations is ostensibly utopian: building a better world by eradicating disability. For example, Autism Speaks, an organization that purports to represent the interests of the autistic community, still foregrounds “solutions” for autism, despite the fact that most autistic people are not interested in being cured and view their autism as a sociocultural identity and experience, not a disease. The vision of groups like Autism Speaks is arguably dystopic, imagining a world where a swath of humanity has been eliminated for its own good—an argument that we’ve seen play out before. In 1927, Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. concluded that the state has a compelling interest in forcibly sterilizing disabled people, infamously writing in Buck v. Bell that “three generations of idiots are enough.” Devaluing disabled lives did not stop there. During the coronavirus pandemic, care rationing of ventilators and some kinds of treatment targeted disabled people—some of whom, like Sarah McSweeney in Oregon, died because of it. Additionally, euthanasia continues to be pushed on the disability community by some proponents of “right to die” legislation who imply that disability alone is grounds for physician-assisted suicide.

To conceptualize what disability in utopia might look like, it’s critical to understand disability as an identity rather than an adverse life experience, as the noted science fiction author and visionary MacArthur Fellowship recipient Octavia Butler did with hyper-empathy syndrome in Parable of the Sower (1993). Sower is the first in a two-book series that presciently takes on climate change and economic inequality, featuring a young woman, Lauren, who feels the emotions of those around her, such as pain or fear. She escapes into the world of her mind, developing the beginnings of a religion, Earthseed. While her disability is only one element of Lauren’s intense experiences, it’s an important part of who she is and how she relates to the world.

“Are you fit?”: A movie poster for the 1934 film Tomorrow’s Children, which criticized the legal eugenic practices of the era.(IMPC via Getty Images)

Disabled people can and do lead fulfilling, rewarding lives—sometimes because of the disability, not in spite of it. Their experiences are diverse: Not all disabled people feel the same way—many do want to be cured or do not view disability as something to celebrate. It’s a big community: About 26 percent of Americans live with an impairment that affects the way they interact with the world, and with long Covid and PTSD originating in traumatic climate events, those ranks are swelling.

Disability culture is lively, complex, and integral to society. But even talented writers and filmmakers struggle to envision how disability might manifest itself in a utopian society. Utopia, they reason, should have ramps and elevators, way-finding tools for blind and low-vision people, and interpreters for the Deaf community. This future is much like the present, but with broader doorways. It is the kind of policy-centric utopia seen in Adolf Ratzka’s 1998 short story “Crip Utopia,” which depicts a world in which everything is accessible and no one needs to fight for elevators or file repeated insurance appeals.

Focusing on accommodations, however, leaves out more visionary possibilities. In addition to physical access, one might consider emotional access, or what Mia Mingus terms “access intimacy,” which she defines as “that elusive, hard to describe feeling when someone else ‘gets’ your access needs.” It is a much deeper approach than merely adding ramps. It recognizes access as a complicated, evolving need that may interact with other aspects of someone’s identity and experience; for example, a Black woman who develops PTSD after witnessing police violence may experience triggers in ways that vary depending on where she is, feeling safer in Black spaces than white ones or needing more support in environments that remind her of her traumatic experience. It is a fundamental element of “cripspace”: spaces curated by and for the disability community, with the needs of disabled visitors emphasized.

A utopian cripspace captivated viewers of Nicole Newnham and James LeBrecht’s Oscar-nominated Crip Camp (Netflix, 2020), which provided a lively, intimate, and disability-centric glimpse into the independent-living movement. The film revolves around Camp Jened, a summer camp for disabled youth where disability is embraced, welcomed, and honored rather than simply being accommodated, a revolutionary experience for people who may have spent their whole lives feeling shut out. Such spaces can be intimidating for nondisabled people, who are not accustomed to being in environments that do not cater to their needs and expectations, let alone those that celebrate disability instead of hiding from it. This is a striking reversal of the usual narrative, and thus, in its own way, is a utopia for disabled people who want to be the heroes of their own narratives, not plot devices in others’.

A cripspace is an environment that pushes back on cultural attitudes about disability; it is a room where disability is at the center of the conversation, one where all participants strive to make sure everyone is included. That may involve making way for a wheelchair or ensuring that someone can see the sign language interpreter, but it also includes honoring differing lived experiences of disability and holding space for one another. Cripspaces do not just respect disability identity. Race, gender, sexuality, class, parenting status, adoptee experience, and more are considered in a cripspace, and their interactions with disability are acknowledged.

The cripspace engages with difference in a way that can and should inform utopias, which typically function by eliminating difference. The consequences of things like “colorblind” ideology are both painful and obvious in the present moment but are ignored in visions of the future. The cripspace knows what society struggles to understand: Pretending that differences do not exist does not eliminate them; it just shuts people out.

In a culture where disability is unwelcome, its presence in utopia may be unsettling to some, but society can benefit from conjuring worlds that model diversity and inclusion, where differences are celebrated rather than flattened.

s.e. smithTwitters.e. smith is a National Magazine Award–winning Northern California-based journalist focusing on disability, culture, gender issues, and rural America.