Detroit Is More Than Just a Melting Pot

With a storied legacy of collective organizing, the future of the working class can still be found in the Motor City.

This story is part of States of Our Union, a series presented in collaboration between The Nation, Magnum Photos, and the Economic Hardship Reporting Project.

As the election draws the country’s attention toward swing states like Michigan, eyes inevitably drift toward Detroit, the state’s population center and one of the Blackest major cities in the country.

We know why. Biden couldn’t have won Michigan in 2020 without carrying metro Detroit. And once the polls closed, Trump’s crusade to bulldoze our democracy rolled through the Motor City before collapsing under a wave of organized opposition from everyday people here. And more recently, both the Democratic Party and Vice President Kamala Harris’s campaign have been haunted by the Biden administration’s sponsorship of Israel’s genocidal war in Gaza and now Lebanon. As Biden and Harris continue to arm the slaughter and refuse to impose any costs on Israel for it, they risk driving Dearborn’s majority-Arab population further away and costing themselves the election in the process.

But this is only one small corner of Detroit’s fluorescent democratic culture. If you only pay attention to voter turnout every four years, then you’re missing all the best stuff—the democracy in our workplaces, neighborhoods, and sprawling grassroots networks.

How We Got Here

Metro Detroit is a mosaic of cultures and traditions. At times, they fold into one another, turning the mosaic into a kaleidoscope.

Like in the reawakening union movement. Or the summer 2020 uprisings following George Floyd’s murder. Or in the furious opposition to our government arming and defending Israel’s evisceration of Gaza.

Before all that though, the city’s early- and mid-20th Century working class only had a few common aspirations working as a bridge between their different worlds.

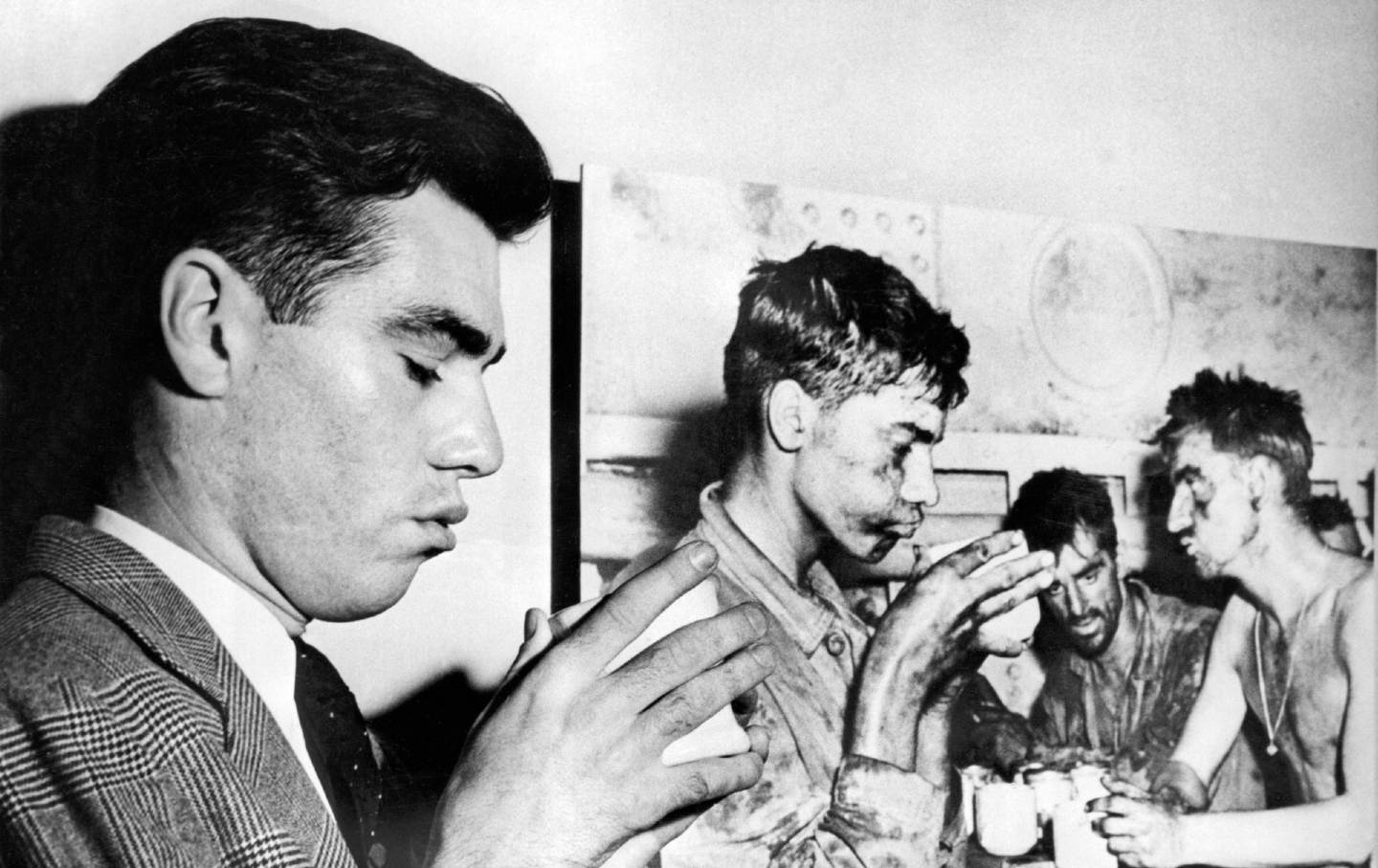

It’s a well-known story by now. Detroit’s booming automotive industry drew a steady stream of determined immigrants, most of them fleeing poverty or oppression and arriving here with the hope of having a little more say in deciding their destinies.

Eastern, Southern, and Central Europeans. Black Southerners sprinting as far and as fast away from the Jim Crow South as they could. The Latino communities that made Southwest Detroit impossibly rich with life. And our vibrant Arab and South Asian enclaves—families of Chaldean Iraqis, Palestinians, Lebanese, Yemenis, and Bangladeshis spanning Detroit, Dearborn, and Hamtramck.

“Lured by the promise of freedom and opportunity that was denied to them,” Thomas Sugrue writes in The Origin of the Urban Crisis, rivers of immigrants flowed into the Motor City from every corner of the planet.

What We Built

These new Detroiters were determined to have some control over their lives. So they got involved in the areas where group decisions get made—in their workplaces, neighborhoods, and City Hall. In each case, they faced powerful opponents who saw sharing power with the public as a direct threat to their enormous fortunes.

It’s clear why: Detroit is an overwhelmingly working-class city. Genuine majority rule would likely lead to outcomes that favor the many over the few. Wealthy car companies that made a killing working workers into the ground did not want their input on how to run Ford, GM, or Chrysler. A racist real estate industry that locked Black and brown families into crumbling ghettos was not eager to have its business methods held up to the light. And politicians who let these local oligarchs profit off working families’ pain did not want the public channeling their anger at remaking local government to serve everyday people.

It didn’t take folks long to realize that their fates were tied together. The labor movement rose on this principle. When Ford finally recognized the UAW in 1941, Black and white workers led the strike that forced them to negotiate. With Detroit as its center of gravity, militant and increasingly diverse unions won real victories for workers on wages, working conditions, and benefits in the decades that followed.

What We Learned

Like everywhere else, the backlash from Detroit’s corporate class against unions, regulations, taxes, and democratic institutions was swift and ruthless. Groups like the League of Revolutionary Black Workers tried to build an opposition with a fighting chance. But corporations were winning their “one-sided class war,” as UAW president Douglas Fraser put it in 1978, against everyone who wasn’t already wealthy or well-connected.

Once the union movement collapsed, so too did the middle class, as multinational corporations left town to more ruthlessly exploit low-wage workers around the globe. The city’s tax base crumbled as white families flocked to segregated and federally subsidized suburbs. Neighborhood segregation and poverty deepened in Detroit.

The labor movement and civil rights movement were now in shambles. Electoral politics became the last arena for the city’s struggling majority to achieve any type of progress.

Detroiters have enormous democratic imaginations, despite our institutions’ rarely delivering democratic outcomes.

Fortunately, the lessons ricocheting around union halls and communities across the country have also been absorbed here. Without outside movements to pressure and keep politicians up at night, private power beats the common good every time.

Detroit is one of history’s great battlegrounds for workplace democracy. And now the UAW and other unions are beginning to use their muscle to pick smart fights again and force companies to fairly compensate workers for the wealth they’ve created. And nearly every corner of the city has some grassroots group waging a heroic uphill battle against corporate titans and the political establishment on housing, public schools, transportation, the energy system, Palestinian freedom, and so much more.

Disobey authoritarians, support The Nation

Over the past year you’ve read Nation writers like Elie Mystal, Kaveh Akbar, John Nichols, Joan Walsh, Bryce Covert, Dave Zirin, Jeet Heer, Michael T. Klare, Katha Pollitt, Amy Littlefield, Gregg Gonsalves, and Sasha Abramsky take on the Trump family’s corruption, set the record straight about Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s catastrophic Make America Healthy Again movement, survey the fallout and human cost of the DOGE wrecking ball, anticipate the Supreme Court’s dangerous antidemocratic rulings, and amplify successful tactics of resistance on the streets and in Congress.

We publish these stories because when members of our communities are being abducted, household debt is climbing, and AI data centers are causing water and electricity shortages, we have a duty as journalists to do all we can to inform the public.

In 2026, our aim is to do more than ever before—but we need your support to make that happen.

Through December 31, a generous donor will match all donations up to $75,000. That means that your contribution will be doubled, dollar for dollar. If we hit the full match, we’ll be starting 2026 with $150,000 to invest in the stories that impact real people’s lives—the kinds of stories that billionaire-owned, corporate-backed outlets aren’t covering.

With your support, our team will publish major stories that the president and his allies won’t want you to read. We’ll cover the emerging military-tech industrial complex and matters of war, peace, and surveillance, as well as the affordability crisis, hunger, housing, healthcare, the environment, attacks on reproductive rights, and much more. At the same time, we’ll imagine alternatives to Trumpian rule and uplift efforts to create a better world, here and now.

While your gift has twice the impact, I’m asking you to support The Nation with a donation today. You’ll empower the journalists, editors, and fact-checkers best equipped to hold this authoritarian administration to account.

I hope you won’t miss this moment—donate to The Nation today.

Onward,

Katrina vanden Heuvel

Editor and publisher, The Nation