Over the last year, Doctors Without Borders has faced a major scandal, as more than 1,000 current and former employees signed on to a letter accusing the Nobel Peace Prize-winning humanitarian organization of institutional racism, citing a colonial mentality in how the group’s European managers view the developing world.

Such an allegation would be serious in any field, but it deserves another level of scrutiny in the context of global health and humanitarianism, two fields built on a paternalistic premise: rich white people from wealthy nations setting themselves up as saviors of poor people of color. The assumptions embedded in this model have provoked increasingly popular calls to “decolonize” the sector, and many organizations have responded by invoking social justice rhetoric, claiming, for instance, that their work intersects with the Black Lives Matter movement.

While it remains to be seen how Doctors Without Borders responds to the charges, the unfolding conflict brings into focus the colonialist premises that underpin the work of many leading institutions, including the most powerful—and perhaps the least diverse—actor in global health and philanthropy: The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.

The foundation promotes itself as “fighting poverty, disease, and inequity,” but it does so from an extremely narrow point of view. It’s governed by two people, Bill Gates and Melinda French Gates, who continue to cochair the foundation following their divorce. Until recently, there was a third member of the board of trustees—another white multibillionaire, Warren Buffett.

The blind spots of this leadership became fatally apparent during the pandemic, when the Gates Foundation positioned itself at the center of the global effort to deliver Covid vaccines to poor nations. That project failed spectacularly, as the foundation partnered closely with pharmaceutical companies even as Big Pharma prioritized delivering vaccines to the most lucrative markets.

Even today, many poor nations have no access to Covid vaccines—a situation that has been described as “vaccine apartheid.”

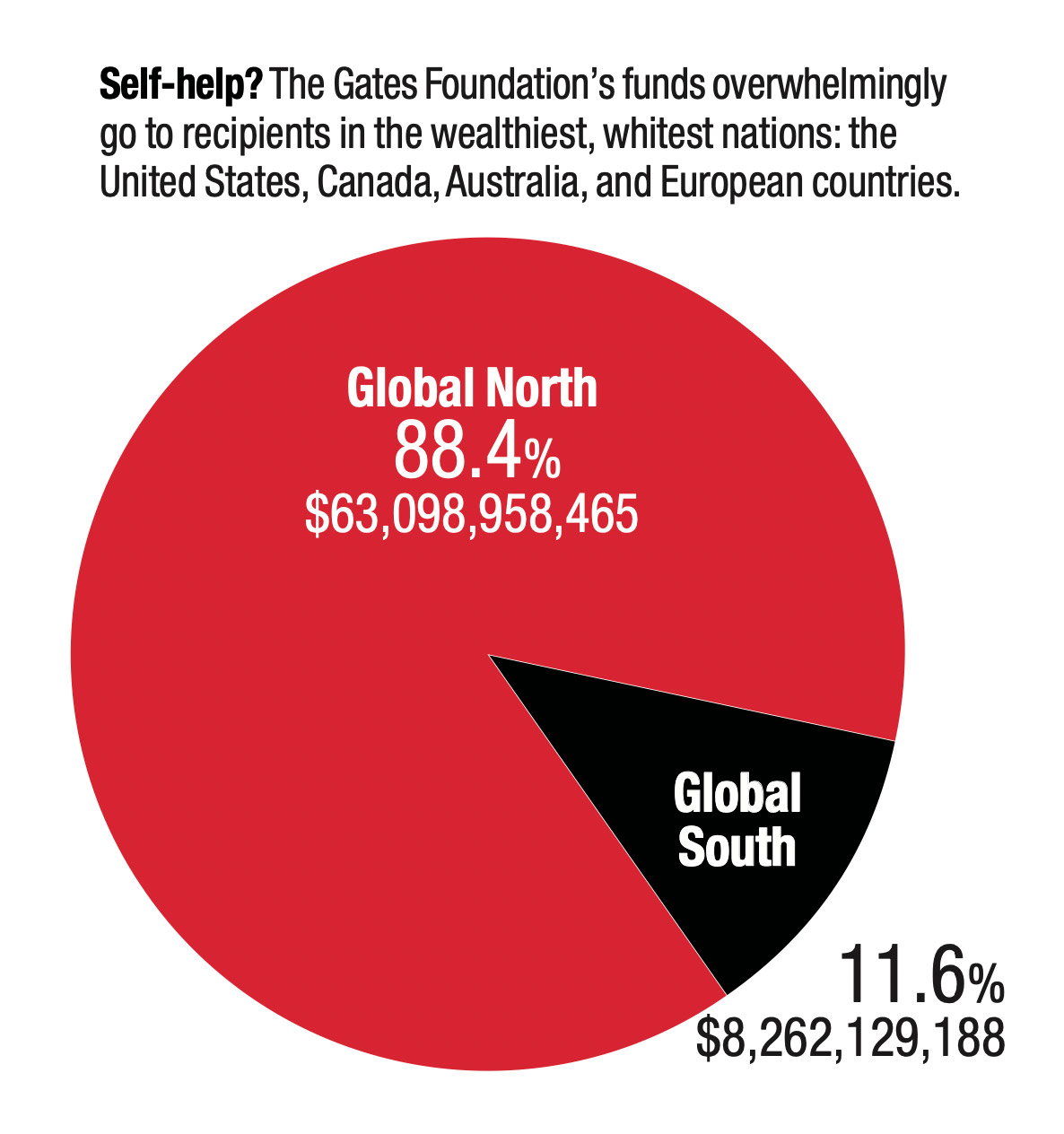

But that’s a criticism the Gates Foundation is unlikely to hear. Its decision to partner with Big Pharma during the pandemic speaks to how the charity has long depended on the rich and the powerful. Though its website is adorned with pictures of poor Black and brown people from the Global South, the foundation overwhelmingly directs its dollars to institutions based in the Global North.

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →The Nation examined 30,000 charitable grants the foundation has awarded over the past two decades and found that more than 88 percent of the donations—$63 billion—have gone to recipients in the wealthiest, whitest nations, including the United States, Canada, Australia, and European countries.

These findings are not new. In 2014, the advocacy group GRAIN found that the vast majority of the foundation’s agricultural funding, though heavily focused on improving African farming, actually goes to universities, institutes, and NGOs based outside of Africa—mostly in North America and Europe. GRAIN issued a follow-up report this summer that found the funding trend had not changed.

As far back as 2009, a study in The Lancet highlighted the same problem in the Gates Foundation’s work in global health: It funds the rich to help the poor.

“They really epitomize a form of charity which is disempowering to the people that they claim to seek to benefit,” says David McCoy, professor of global public health at Queen Mary University of London and lead author of the Lancet study.

“It comes back to this issue of power,” McCoy continues. “At the end of the day, a really good metric…to look at is: Has power been redistributed over the last 20 years since the Gates Foundation has been on the scene? And I think the evidence shows it hasn’t. If anything, inequality—in terms of power—[has] actually gotten worse. There’s been an even greater concentration of power and wealth in a few hands, even if lives have been saved during that time. By continuing to not address the more fundamental problems of structural inequality, and the injustice of that, they are able to maintain this position of being charitable and benevolent, which they are then able to translate, to turn into social power.”

Yadurshini Raveendran says that when she embarked on her graduate degree at Duke University, her coursework in global health partook of a troubling “us versus them” framework: capable, competent experts and institutions from the Global North rescuing the helpless, unwashed masses from the Global South.

Raveendran realized that others in the class shared her discomfort, which led to the formation of the Duke Decolonizing Global Health Working Group, one of a growing number of campus activist groups pushing back on the colonialist mentality they see embedded in university curricula.

A paradox in this activism, Raveendran notes, was that her studies at Duke were partially funded by a scholarship from the Gates Foundation, which enabled her to move from Sri Lanka to study in the United States.

“I’m grateful that I had that scholarship, because otherwise I would not have been able to come here and do my work,” Raveendran says, before adding a quick caveat: “Why did I have to leave my home country to get an education in public health here, in this part of the world, in order to help my people? It’s just really ironic. I had to take a handout from a white organization, when it was a white organization—the British Empire—that colonized my land.”

Raveendran says such contradictions will continue to play out in her career, because the Gates Foundation funds virtually every organization working in global health.

“They are the antithesis of the decolonial movement, because they are the system. They perpetuate the system that is causing harm. If we were to decolonize, we would dismantle the system of aid where another country or another organization has put in their money in order for us [in the Global South] to be healthy,” she says. “I can’t blame [Bill] Gates as being the sole perpetrator, because this is centuries of harm, but he is part and parcel of that conversation, for sure, because of how much power he is wielding.”

Seye Abimbola, a senior lecturer in the School of Public Health at the University of Sydney, describes the Gates Foundation’s work in global health as a kind of privileged navel-gazing: deciding what poor nations need, implementing “surgical interventions” to address these needs, then pouring money into evaluating how well its programs work. “The kinds of things that the Gates Foundation funds would be to generate evidence that we don’t need…. That has had a huge, destructive, and wasteful effect,” he says. “I need a system that allows me to learn over time…to learn by myself, for myself.”

Abimbola points to one of the foundation’s most heavily funded projects, the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation at the University of Washington, which produces widely used estimates that supposedly track the prevalence of disease at a granular level in virtually every village throughout sub-Saharan Africa. The IHME has received more than $600 million from the Gates Foundation, but the methods, accuracy, and ethics of its health estimates have drawn widespread criticism. Scholars describe the IHME as a monopoly and a model of “data imperialism”—an effort to flatten the Global South into a series of numbers.

“It creates an illusion of knowledge. It tells people in a lot of [poor nations] that they don’t know what they know about themselves. That what you think you know, you don’t know,” Abimbola says. “That is the colonial experience.”

Shades of this criticism color virtually all of the foundation’s work. In July, Scientific American published an op-ed titled “Bill Gates Should Stop Telling Africans What Kind of Agriculture Africans Need.” One of the coauthors, Million Belay, a coordinator at the Alliance for Food Sovereignty in Africa, noted in an interview that the foundation’s charitable work on African agriculture bears all the hallmarks of colonial power: seeking to modernize and civilize Africa while also advancing commercial interests, like pushing farmers to buy genetically modified seeds, chemicals, and other technology from multinational companies headquartered outside of Africa.

“When our agriculture is considered backward, and the only solution proffered is technology, then there is a civilization agenda,” Belay says. “And that civilization agenda is not to civilize us but to bind us to the vagaries of this technology.”

Even the Gates Foundation’s work at home, in K-12 education, has been described as “a colonizing, neutralizing, and supervising force in Black schools and communities.”

That’s from Alison Ragland’s PhD dissertation, which examines the foundation’s aggressive efforts to remake schools in low-income districts through educational standards, testing, and technology. Ragland, a consultant and former teacher, describes the foundation as part of an educational reform movement that overwhelmingly focuses on “access,” steering Black students into white corridors of power in ways that can disempower them from thinking critically about the root causes of inequality. “I focus on teaching about systems of oppression so that people can understand where they come from, where they fit into that system of oppression, so that when they see unequal power dynamics they can more easily recognize it, call it out, and do something about [it],” Ragland says. “In the absence of a critique of the entire system of oppression…we’re going to be stuck on only making spaces steeped in white supremacy more accessible to people who have been excluded from those spaces.”

By distracting students from serious, critical thinking about inequality, the Gates Foundation also distracts them from scrutinizing its own immense wealth and power—thereby preventing them from challenging its undemocratic role in shaping US education.

“The master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house,” says Ragland, quoting the writer Audre Lorde.

Edgar Villanueva says that in the world of philanthropy, conferences and meetings are increasingly dominated by discussions of “DEI” (diversity, equity, and inclusion), an effort to persuade private foundations to bring more people of color into leadership positions, provide charitable dollars directly to affected communities, and align their endowments with their charitable mission.

Villanueva has become a leading voice in this movement since the publication of his 2018 book Decolonizing Wealth, which interrogates the “colonizer virus” embedded in philanthropy—a field he defines as “mostly white saviors and white experts versus poor, needy, urban, disadvantaged, marginalized, at-risk people.”

“The process starts with asking the question ‘Where does the money come from?’” Villanueva says. “If you think about it through the place of truth and reconciliation, it begins with looking back and asking what harm has been done. I think for a lot of foundations…the work is very much looking forward, like ‘What do we do in the future?,’ without taking into account what happened in the past.”

For his part, Bill Gates says he sees nothing to apologize for in the source of his wealth; he considers his work at Microsoft to be a greater achievement than any humanitarian work he has undertaken through the foundation.

This self-appraisal ignores a long legacy of destructive behavior that has been uncovered by investigations into Microsoft’s anti-competitive business practices, tax avoidance, gender discrimination, and exploitation of low-paid migrant workers. Recently, the company has been criticized for its investments in Israeli surveillance and military technologies.

As these business practices may boost Microsoft’s bottom line and expand the personal wealth of Bill Gates and Melinda French Gates, they also contribute to a growing political debate about the problems with capitalism, which increasingly is a debate about equity and social justice.

French Gates, when asked to address such issues on CNBC in 2019, responded with a laugh: “When I go to places like Malawi or Tanzania or Senegal, they say they all want to live in America. We are lucky to live here. They want to live in these types of capitalistic societies.”

It’s a stunning statement that misconstrues the role that capitalism has played in the history of these “unlucky” African nations, from the slave trade to European colonization to today’s cash-crop economies. For the Gates Foundation, these struggling economies appear as a blank slate onto which it can write its own ambitions.

In Tanzania, for example, the foundation funds a raft of projects by American and European companies, consultants, think tanks, universities, and NGOs—Elanco, Land O’Lakes International Development, Exosect, TechnoServe, Rockefeller Philanthropy Advisors, Purdue University, World Resources Institute—which act to strengthen the country’s property rights, change diets, introduce pesticides, industrialize agriculture, and reorient health policies.

The Gates Foundation didn’t issue a DEI statement until May of this year, when it offered a perfunctory commitment to “a future that is more diverse, equitable, and inclusive for all.”

That statement follows other belated and shallow reflections that the foundation has expressed over the years about its outsized privilege. “It’s not fair that we have so much wealth when billions of others have so little,” the Gateses wrote in an annual open letter from the Gates Foundation in 2018. “And it’s not fair that our wealth opens doors that are closed to most people. World leaders tend to take our phone calls and seriously consider what we have to say. Cash-strapped school districts are more likely to divert money and talent toward ideas they think we will fund. But there is nothing secret about our objectives as a foundation. We are committed to being open about what we fund and what the results have been.”

It’s an odd logic, arguing that the lack of secrets at the foundation somehow justifies its undemocratic power. And it’s built on a patently false premise: the idea the Gates Foundation is transparent. The foundation’s CEO, Mark Suzman, has stated that its commitment to diversity, equity, and inclusion depends on “transparency and accountability,” yet neither he nor the foundation responded to multiple inquiries from The Nation, including basic queries about the racial composition of the groups it funds or its staff, or requests to discuss its work on race and equity.

The Gates Foundation is testing the limits of its power by refusing to engage with the rapidly expanding conversation around decolonization. Scholars, writers, and activists are publishing on this topic in Forbes, The Washington Post, The Guardian, and elsewhere, and the growing debate will continue to pressure the foundation to justify the logic of its power. To explain the collateral damage in its bullying crusade to help the poor. To reckon with the difference between giving away money and actually sharing power.

“Will global health survive its decolonisation?” asked a recent article in The Lancet cowritten by Seye Abimbola. “Perhaps. But only if its practitioners commit to its true transformation. A crucial first step is recognising that ours is a discipline that holds within itself a deep contradiction—global health was birthed in supremacy, but its mission is to reduce or eliminate inequities globally. To transcend its origins, global health must become actively anti-supremacist, and also anti-oppressionist and anti-racist. Equity and justice involve flipping every axis of supremacy on its head.”