The Time George Foreman Sang Me Some Dylan

With the passing of the boxing legend, I want to recall an interview I never expected and will never forget

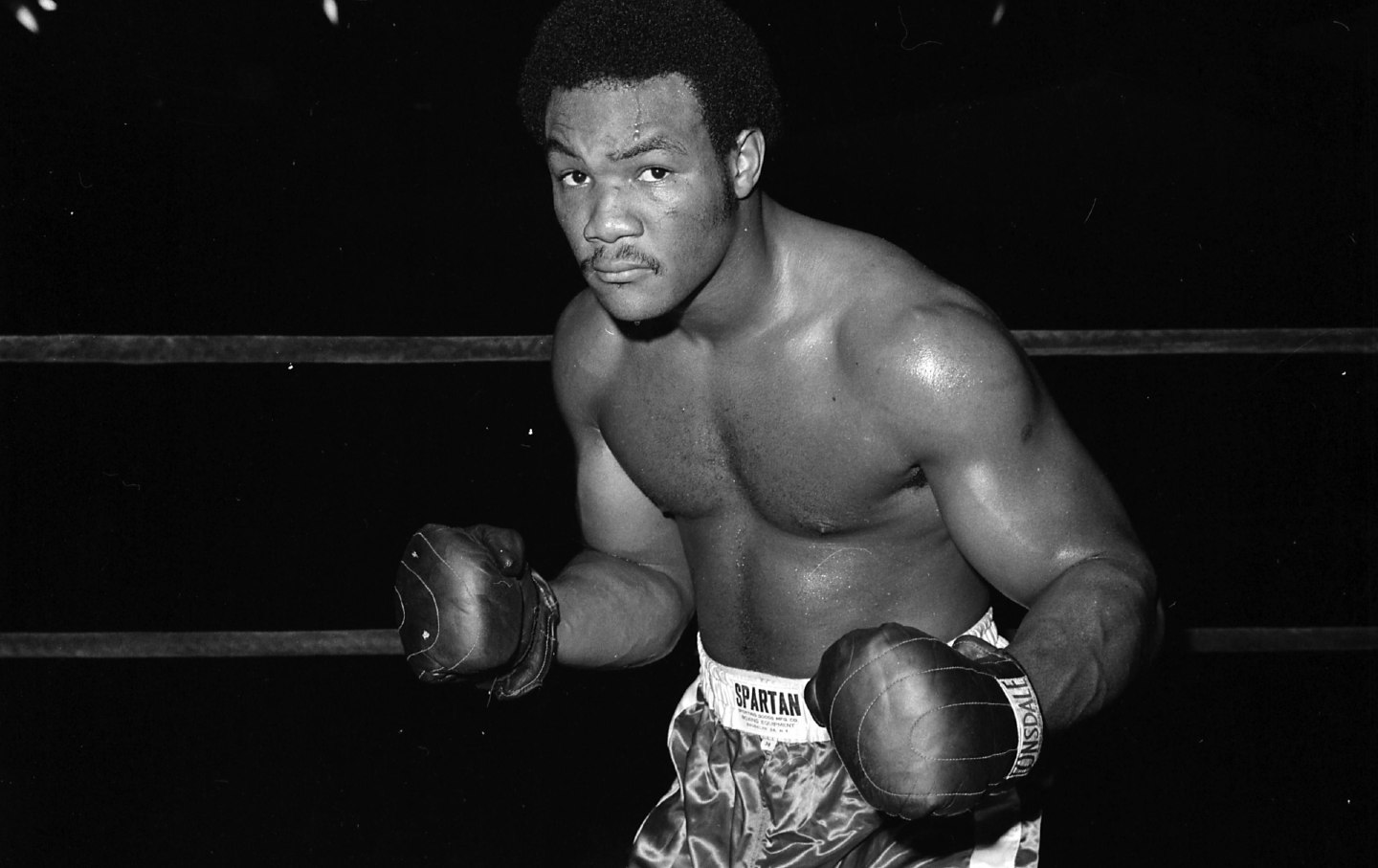

George Foreman poses as he trains in 1972 in New York, New York.

(The Ring Magazine via Getty Images)

Back when I was a young reporter, I needed to interview former heavyweight champion, boxing legend, and grill impresario George Foreman. It would have been the third sports interview of my life. The first was with 1968 Mexico City Olympic medalist and medal-stand protester John Carlos. The second was with another 1968 Olympic rebel, record-setting sprinter Lee Evans. I had asked them both about their 19-year-old Olympic teammate George Foreman who, after winning the heavyweight gold medal, waved a small American flag and bowed to all four sides of the ring. This happened just days after Carlos and fellow medal stand protester Tommie Smith had been expelled from the Olympic Village and told to go home. The media read Foreman’s move as a rebuke of their actions. To my surprise, both Carlos and Evans defended Foreman. They said they loved “Big George” and never saw his flag-waving as a reprimand. This was unexpected, given that every history of the storied 1968 games that I had read described it as exactly that.

I realized I needed to ask Foreman himself, but the problem was that I had no idea how to find him. This was still the early days of the Internet, before you could shoot someone a DM or track down a publicist by simply tapping out a few words on Google. Instead, I had to start by going to a search engine called Ask Jeeves, which required searches to be framed in the form of a question. I proceeded to ask Jeeves, “How do you contact George Foreman?” Jeeves’s only response was a link to the George Foreman Grill website. Thanks for nothing, Jeeves.

It was the end of the day, and I thought I’d take a shot in the dark. I went to the site and clicked on the “contact us” link, meant for people trying to reach a customer-service representative. In the small window that popped up, I submitted a message noting that my Grill was fine, but I was a reporter hoping to interview Foreman about the 1968 Olympics. At best, I thought, my e-mail might get referred to a publicist of some kind who, if I was lucky, would send a response in a few days. That’s not what happened.

Ten minutes later, just as I was about to leave the office, I received an e-mail that read simply, “Hey, this is George. Here’s my phone number. Give me a ring.” After regaining my breath, I called, my hands clammy, and, sure enough, Foreman picked up. What followed was an unforgettable two-hour conversation. Utterly unprepared, I came up with questions on the fly. Even worse, the telephone recording equipment had been checked out of the office, so I was forced to use my horrible computer shorthand. Eventually, I was the one to end the interview because my hands were cramping.

I wanted to hear about 1968, but also about his life leading up to Mexico City. I asked him when he was first aware of the Black freedom struggle. He started by talking about the extreme poverty of his youth, when even a school lunch was out of his reach. “Growing up poor, I didn’t even have a lunch to take to school,” he recalled “Lunch was 26 cents, and we didn’t even know what 26 cents looked like.” Life was survival. That changed when he was hired at a public works jobs program as a 16-year-old, and a “young Anglo-Saxon boy from Tacoma, Washington,” introduced him to Bob Dylan. I asked him what Dylan song opened his mind about the state of the world. I thought he’d say “The Times They Are A-Changin’” or “Blowin’ in the Wind.” Instead, he invoked “Rainy Day Women Number #12 and 35”—the first track on the 1966 album Blonde On Blonde. “Do you know that one?” Foreman asked. Before I could answer, he started to sing. In a voice richer and deeper than I had expected, he crooned, “Well, they’ll stone ya when you’re walkin’ ’long the street. They’ll stone ya when you’re tryin’ to keep your seat. They’ll stone ya when you’re walkin’ on the floor. They’ll stone ya when you’re walkin’ to the door. But I would not feel so all alone. Everybody must get stoned.” When he’d finished, he asked me if I understood what Dylan was trying to say. Taken off guard, I said, “I think he’s singing about weed?”

“Bite your tongue, young man,” Foreman shot back. “That song is about the way people are always trying to put you down—and if anybody tries to say or do anything, we’ll get stoned. It’s about Jesus and being strong in difficult times.” I mumbled back, “I still think it’s probably also about weed,” and he said, “Shame on you, young man.”

Given that we had only been speaking about 10 minutes, and I was not sure if the born-again preacher was actually annoyed, I pivoted quickly and asked him what his thoughts were as a young boxer when, in 1964, newly minted heavyweight champion Cassius Clay changed his name to Muhammad Ali. He said it terrified him that people were calling Ali a “Black Muslim.” I asked him if the scary part was Ali’s rejection of Christianity and conversion to Islam, a shock to the world and something no star athlete had yet to do publicly. George said, “Heck no! What scared us was that people were calling him Black! The word frightened everybody. No one had heard the word Black in Texas to describe a so-called ‘Negro’ at that time. Everyone was saying he was crazy.”

We kept talking. There was one yarn he told about sparring with Jimi Hendrix, which is still unimaginable to me. I see Jimi, outweighed by George by probably close to 100 pounds, in a feather boa, throwing jabs. Then again, given Jimi’s army experience and famously large hands, maybe they were able to have a good tussle.

I was so dizzy from this conversation, I almost forgot to ask him about 1968 and why he waved that flag. When I did, he started his answer by describing how track stars like Carlos and Smith were seen like rock stars every time they entered the Olympic Village and how he, as a teenage Olympian, four and five years younger than they were, looked up to them in awe. He said that when they were kicked out of the Olympic facilities and forced to go home, he had a strong urge to leave with them. Instead, he stayed, won gold, and waved that flag.

True to what Carlos and Evans had told me, Foreman said it had nothing to do with them. After an upbringing of hunger and poverty, he was just feeling overcome with gratitude toward the United States. This was a very different perspective on the Olympics from that of Carlos, who, after returning home to Harlem, explained why he protested, saying, “I can’t feed my children with medals.” Still, 35 years later, Carlos and Evans refused to sit in judgment of what was, at worst, a naïve display of patriotism. They were confident that they knew what was in his heart. They never thought for a moment that their mammoth “little big brother” would be taking him to task.

There was more to the interview, but I’ll leave it there. A section of it was published in Counterpunch and a section in The Source. But the published copy will always be secondary in my mind to the fact that George Foreman, for some reason, was at Grill headquarters willing to give two hours to somebody he didn’t know. I think about him whenever there’s a chance to pay it forward.

In the days after Foreman’s death, I spoke to Dr. John Carlos. He shared memories of his old friend and talked about wanting to attend the funeral services. Carlos wants to offer one last show of what was a deeply mutual respect, whether the history books recorded it that way or not.

Hold the powerful to account by supporting The Nation

The chaos and cruelty of the Trump administration reaches new lows each week.

Trump’s catastrophic “Liberation Day” has wreaked havoc on the world economy and set up yet another constitutional crisis at home. Plainclothes officers continue to abduct university students off the streets. So-called “enemy aliens” are flown abroad to a mega prison against the orders of the courts. And Signalgate promises to be the first of many incompetence scandals that expose the brutal violence at the core of the American empire.

At a time when elite universities, powerful law firms, and influential media outlets are capitulating to Trump’s intimidation, The Nation is more determined than ever before to hold the powerful to account.

In just the last month, we’ve published reporting on how Trump outsources his mass deportation agenda to other countries, exposed the administration’s appeal to obscure laws to carry out its repressive agenda, and amplified the voices of brave student activists targeted by universities.

We also continue to tell the stories of those who fight back against Trump and Musk, whether on the streets in growing protest movements, in town halls across the country, or in critical state elections—like Wisconsin’s recent state Supreme Court race—that provide a model for resisting Trumpism and prove that Musk can’t buy our democracy.

This is the journalism that matters in 2025. But we can’t do this without you. As a reader-supported publication, we rely on the support of generous donors. Please, help make our essential independent journalism possible with a donation today.

In solidarity,

The Editors

The Nation