What Harm Reduction Really Looks Like

Harm reduction advocates are implementing solidarity-based strategies for curbing drug overdoses in Minneapolis.

This story was copublished and supported by the journalism nonprofit the Economic Hardship Reporting Project.

Afew strands of Christmas lights flicker from nearby houses as Shannon Clancy hangs up her phone and gazes through the windshield towards the shadowy, sleepy block ahead. “She’s worried he might lose his leg,” Clancy says. Her voice is gentle and measured, yet subtly weighted with grief.

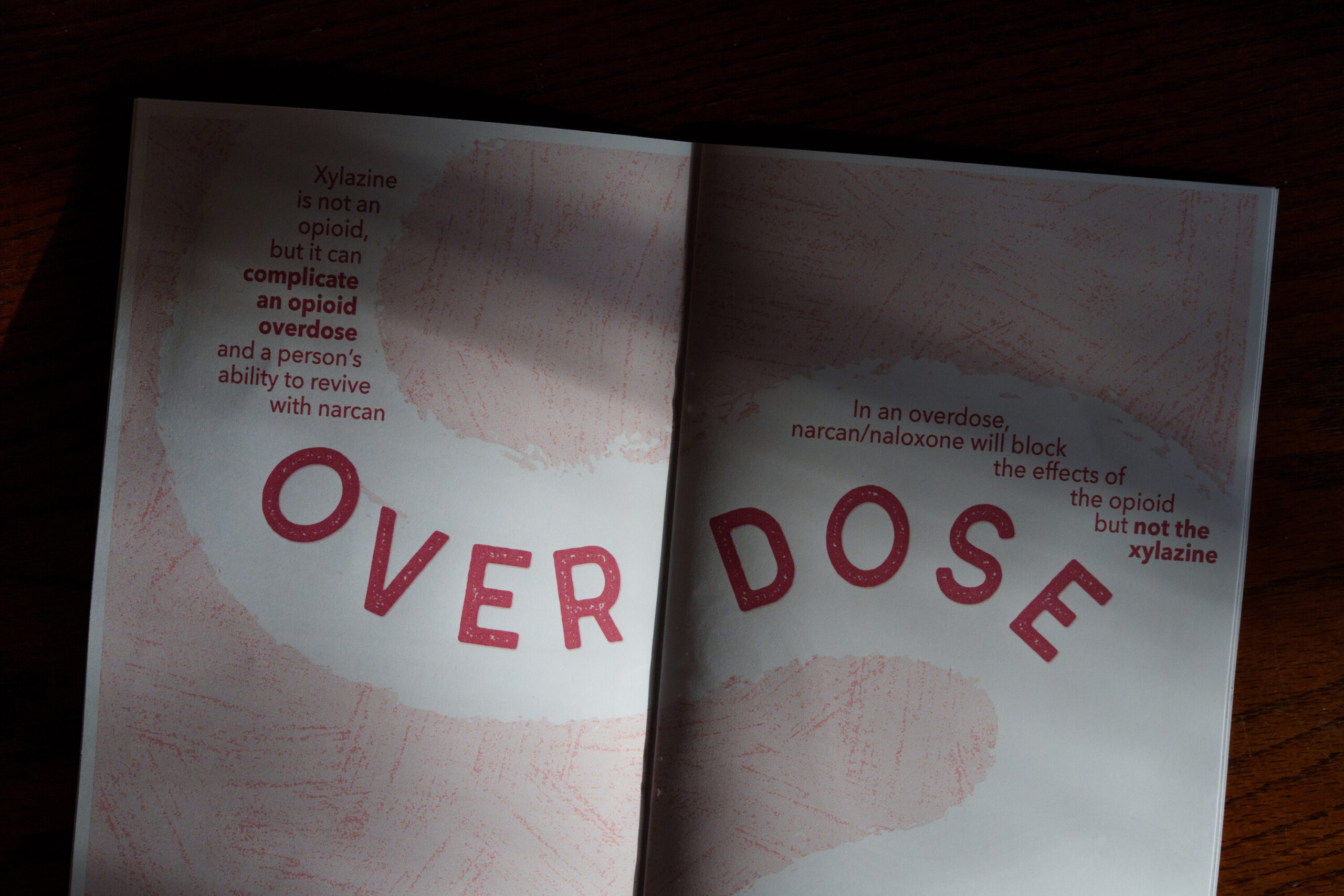

It’s a snowless December night, and Clancy, the education and overdose prevention lead at Southside Harm Reduction Services, has just spoken with a program participant in North Minneapolis. The caller’s friend recently used fentanyl likely laced with Xylazine, a powerful tranquilizer cut into drugs to enhance their effects. The man now has a festering wound spreading across his leg. The caller is worried, naturally, but her friend doesn’t like going to clinics. While on the phone, Clancy listens patiently. She acknowledged that clinics can feel judgmental yet stresses that the man should nevertheless seek immediate medical attention. The caller offers thanks, requesting a wound care kit and clean use supplies before ending the conversation.

After a brief pause, Clancy makes her way to the delivery van trunk, where supply-filled bins are neatly nested together. Having placed a brown paper bag of items on the front stoop, Clancy reemerges from the darkness then sets off to the next address.

Clancy’s encounter is an all-too-familiar scene for those on the front lines of America’s harm reduction movement. The overdose epidemic now kills more than 100,000 Americans annually, touching the lives of 40 percent of the population and disproportionately impacting people along class and racial lines. Minnesota, like so many states, has suffered the ravages of this crisis firsthand, with deadly overdoses doubling from 636 to 1272 between 2018 and 2023. As in the case of the North Minneapolis caller, substance users who avoid overdose face other dire health risks. The recent increases in lethality and harm are a part of the third wave of the opioid epidemic, which began in 2013 and is largely attributed to the ubiquity of fentanyl, a synthetic opioid up to 50 times more powerful than heroin. Illicitly produced fentanyl is now regularly cut into the supply of other drugs, making it increasingly difficult to source narcotics that aren’t tainted with the potent opioid and leading to a surge in both addiction and accidental overdoses.

Despite the gravity of the ongoing situation, 2024 brought an unexpected reason for optimism. The Center for Disease Control and Prevention reported last spring that overdose deaths decreased by a startling 10.6 percent nationally between April 2023 and April 2024—a drop closely mirrored by Minnesota’s statewide decrease of 11.5 percent. This marks the largest decline in overdose mortality in decades, by a wide margin.

Experts say a variety of factors drive this unprecedented decrease: users’ growing familiarity with fentanyl, more accessible treatment, and a tightening of the drug supply. Some experts also theorize that overdoses are simply returning to their pre-Covid levels. Another vital factor is the growing implementation of harm reduction, a set of practices proven to mitigate the known risks associated with drug use and other behaviors. While aspects of harm reduction have been gradually folded into mainstream health infrastructure, much of the work continues to be spearheaded on the street level by grassroots communities of often current and former drug users dedicated to supporting their peers. For many such advocates, the approach is viewed as much more than a public health intervention; it’s a way of life that serves as an antidote to entrenched social, racial, and class inequalities.

Harm reduction and the people implementing it

Harm reduction has a long history, originating with drug users and sexually active groups who feel their health concerns are often neglected by medical providers. Motivated by nonjudgmental compassion, participant autonomy, and the “nothing about us without us” credo, impacted communities have developed solidarity-based strategies for maintaining their wellness. In the process, they’ve worked to reframe the traditionally criminalizing approach to drug use with one grounded in risk mitigation. “If people are gonna [use substances]—and people are gonna do it, they’ve been doing drugs forever, it’s not gonna ever end—how do we do it safely?” said James Schmidt, harm reduction outreach lead at Native American Community Clinic (NACC) in South Minneapolis.

Harm reduction practitioners don’t pressure people to stop using substances, nor do they promote the proliferation of drugs. They instead aim to support those in active use, arguing that consuming drugs is a normal—albeit often complex—part of the human experience. This is accomplished through a diverse range of low-barrier services and programs that go far beyond syringe exchanges and the distribution naloxone (aka Narcan), a highly effective opioid reversal medication. Other efforts include infectious-disease testing, the distribution of fentanyl test strips, wound care kits, safe use and sex supplies, Narcan training, used syringe collection and disposal, and education. These practices, as with all harm reduction practices, have emerged based on the needs expressed by impacted communities, with the goal of reducing barriers to resources that are often inaccessible. “People who have been using substances have known how to prevent [associated harms] for so long,” said Marissa Bonnie, harm reduction health educator at NACC. “But when you’re not giving someone the chance to be safer, how do you expect them to not be at risk?”

The intersection of overdoses and housing insecurity

While many Twin Cities harm reduction providers extend support to the community at large, needs vary considerably across the population. Social determinants of health—such as race, wealth, and the strength of one’s social networks—afford a degree of stability that can help insulate substance users against the vulnerabilities faced by those also coping with poverty, criminalization, racial disparities, and homelessness. Unhoused folks indeed feel these dynamics acutely, as they’re approximately six times as likely to die from overdose than those who are low-income and housed. What’s more, the Department of Housing and Urban Development’s 2024 single-night count of unhoused individuals saw an 18 percent year-over-year increase in the number of people without housing. The result is a deepening, intersectional co-crisis between overdoses and homelessness.

Many harm reduction practitioners address this reality by placing special emphasis on supporting unhoused substance users. At Southside Harm Reduction Services, outreach lead Angela Richards, who hails from Pine Ridge Reservation and has worked at the organization since 2021, oversees weekly trips to local encampments. Sometimes, teams visit large, long-established camps, while other days they locate small clusters of tents newly pitched along freeway barriers. On one crisp early winter afternoon, Richards and their colleagues fill a handful of pushcarts with supplies, then load them into a convoy of vehicles. When they arrive at a vacant South Minneapolis lot, a few tents line the sidewalk. Richards kneels by each to see if anyone is inside, handing snack bags, socks, clean pipes, and lists of local resources to those too cold to venture out. “The quality of life of folx who use drugs and are living outside [is not] a priority in our city today,” Richards explained. “I’m able to relate to people and meet them where they’re at because of what I went through. And I’m not far removed. I’m just housed. I’m just in my own form of recovery.” As Richards’s comments underscore, the line between housed and unhoused or addiction and recovery is often thin. For many, the difference can be as simple as a few missed paychecks or a stressful life event, and a recognition of that reality is ever-present among those providing services on the front lines.

Unfortunately, the rise of unsheltered homelessness across the country over the past decade has been increasingly met with forced encampment evictions, often referred to as “sweeps.” This long-standing yet legally murky practice was codified by the 2024 US Supreme Court ruling on City of Grant’s Pass v. Johnson, which declared that evicting, fining, and even jailing people who sleep in parks and public space is not cruel and unusual punishment. In Minneapolis, Mayor Jacob Frey has overseen a contentious, years-long eviction campaign, citing drug use, violence, sex trafficking, property damage, and litter associated with encampments as pretext for enforcement. Encampment residents and activists acknowledge that camps present safety concerns. Yet they argue that the same risks exist outside of the camps, and that the community and stability provided by encampments offer residents more protection against exploitation and overdose than when living in isolation. “After a camp has been evicted,” said Zach Johnson, “that’s the most dangerous part. People are scattered; they lost their stuff; they lost their community; they lost their Narcan. A lot of people use and overdose in the hours after a sweep.”

Encampment residents and supporters have resisted Minneapolis’s ongoing eviction campaign through a range of tactics, including public rallies, protest encampments at City Hall, and clashes with police. Camp Nenookaasi, a predominantly Indigenous encampment originally formed in the economically disadvantaged East Phillips neighborhood in August 2023, has become one of the Twin Cities’ most prominent camps. Its residents, many of whom experience addiction, waged a legal battle against the city, culminating in the filing of a 2024 federal lawsuit against Mayor Frey to halt sweeps. The lawsuit was ultimately dismissed, with the camp’s eventual closure and relocation leading to a familiar cycle of dispossession, displacement, and subsequent spikes in overdose risks that continues through today.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →Among harm reduction advocates, the ultimate goal is to expand access to housing-first accommodations, which don’t impose sobriety requirements. One such solution in Minneapolis is Avivo Village, a low-barrier transitional shelter. Avivo offers individual dwellings, wraparound services, safe use support, and open-ended periods of stay to those experiencing homelessness.

“I have hardly any money, but I don’t care. I have a place to live. And for me, I’m not going behind dumpsters in alleys. I’m not risking that, you know. Because there’s other stuff that happens with being outside and being high as far as risks are concerned. It is important.” —Rick Kooy

As of November 2024, the facility claims to have reversed 214 overdoses and helped 253 residents secure permanent housing. Housing-first approaches are shown to be more affordable and effective in the long term than traditional responses with short-term results, such as sober shelters or criminalization. “Putting people in housing is harm reduction,” said Rick Kooy, who’s lived in a housing-first program for over 10 years and volunteers with SHRS.

The needs ahead

The recent dramatic decline in overdose deaths is a welcomed success, with providers, advocates, substance users, and those who have lost loved ones hoping that this signals a sustainable downward trend in mortality. Yet many stress that there is much work to be done, and that, in certain ways, the need is growing. The emergence of nitazenes—synthetic opioids that are up to 40 times more powerful than fentanyl and increasingly being cut into other drugs—are one example of constantly evolving threats. So, too, is the accelerating criminalization and displacement of unhoused people.

As mounting pressures test people’s resilience, harm reduction advocates nevertheless continue to show up. That’s the case for SHRS staff, as it is for so many others who do the hard but necessary work. For Shannon Clancy, it might mean talking someone through a health crisis; for Angela Richards, offering food and referrals through a tent door; for Zach Johnson, spending hours zigzagging around the city. Either way, it’s people’s commitment to showing up that matters most. Advocates believe that with such commitment—and community—healing remains possible. It’s a truth that SHRS cofounder Jack Martin feels is succinctly captured by the organization’s emblem. “The logo is prairie grass and wildflowers,” Martin explained. “In terms of ecological renewal after disasters, the first things to grow back are usually grass and wildflowers. They offer a very specific role in the regrowth of an environment. The grass and wildflowers bring nutrients to the soil, help stabilize the soil, and allow for bigger things to grow—bushes and eventually trees and then the rest of the forest. I hope that Southside can take on that role within Minneapolis and Minnesota.”

More from The Nation

A Civil Rights Veteran Revisits the Summer of 1965 A Civil Rights Veteran Revisits the Summer of 1965

The white college student supported Black voters in segregated Alabama, and began documenting the front lines of the voting rights fight, which locals continue to disregard.

Notes on Transsexual Surgery Notes on Transsexual Surgery

An abundance of plastic surgery is not a net good. But discussions over its morality would be better off viewing it less as unfettered desire and more as self-determination.

I Led the FDNY. Don’t Believe Elon Musk’s Nonsense About It. I Led the FDNY. Don’t Believe Elon Musk’s Nonsense About It.

Musk’s attack on the new FDNY commissioner proves he knows nothing about how modern fire departments work.

What Black Youth Need to Feel Safe What Black Youth Need to Feel Safe

Young people are facing a mental health crisis. This group of Cincinnati teens thinks they know how to solve it.

Trump’s Death Eaters Are Coming for Our Kids Trump’s Death Eaters Are Coming for Our Kids

After taking countless lives around the world, RFK Jr. and his ghoulish compatriots want American children to suffer too.

The Supreme Court Just Held an Anti-Trans Hatefest The Supreme Court Just Held an Anti-Trans Hatefest

The court’s hearing on state bans on trans athletes in women’s sports was not a serious legal exercise. It was bigotry masquerading as law.