Portland, Ore.—On September 29, a tiny pumpkin sat next to Amber Coughtry’s and Billy Lewnes’ white cross, in a gravel parking lot by Force Lake in Portland. “Gone 2 years” was written on it.

Two years to the day after the pair were killed, birds chirped above an interstate freeway’s roar, golf carts scudded, geese splashed and a dog cavorted on the dashboard of an RV with no license plates. History hung heavy: This spot was home to School Number 3, part of a wartime public housing city named Vanport, which floodwaters washed away in 1948. In 1983, a serial killer dumped a teen girl’s body in a nearby slough.

Coughtry’s mother, Laurie Bushnell, comes to the place to deposit jars of homemade dill pickles. It’s her way of working through grief, and limbo.

“She liked just dill pickles,” Bushnell says of Coughtry—who, as a toddler, would drink juice right from the jar. “It had to be dill pickles. She’d be at the refrigerator going, ‘Pickles! Pickles!’”

Later, Coughtry “spiraled” with depression and drugs, Bushnell says. While residing in vehicles, she and Lewnes survived an RV fire. Then, in a brutal, still-unsolved double homicide, they were shot to death in their car before sunrise. Three days later, Portland Police announced there was “no threat to the community.” The crime faded, popping up in a report and local stories.

Yet these are dots in a line that’s pointing ever higher.

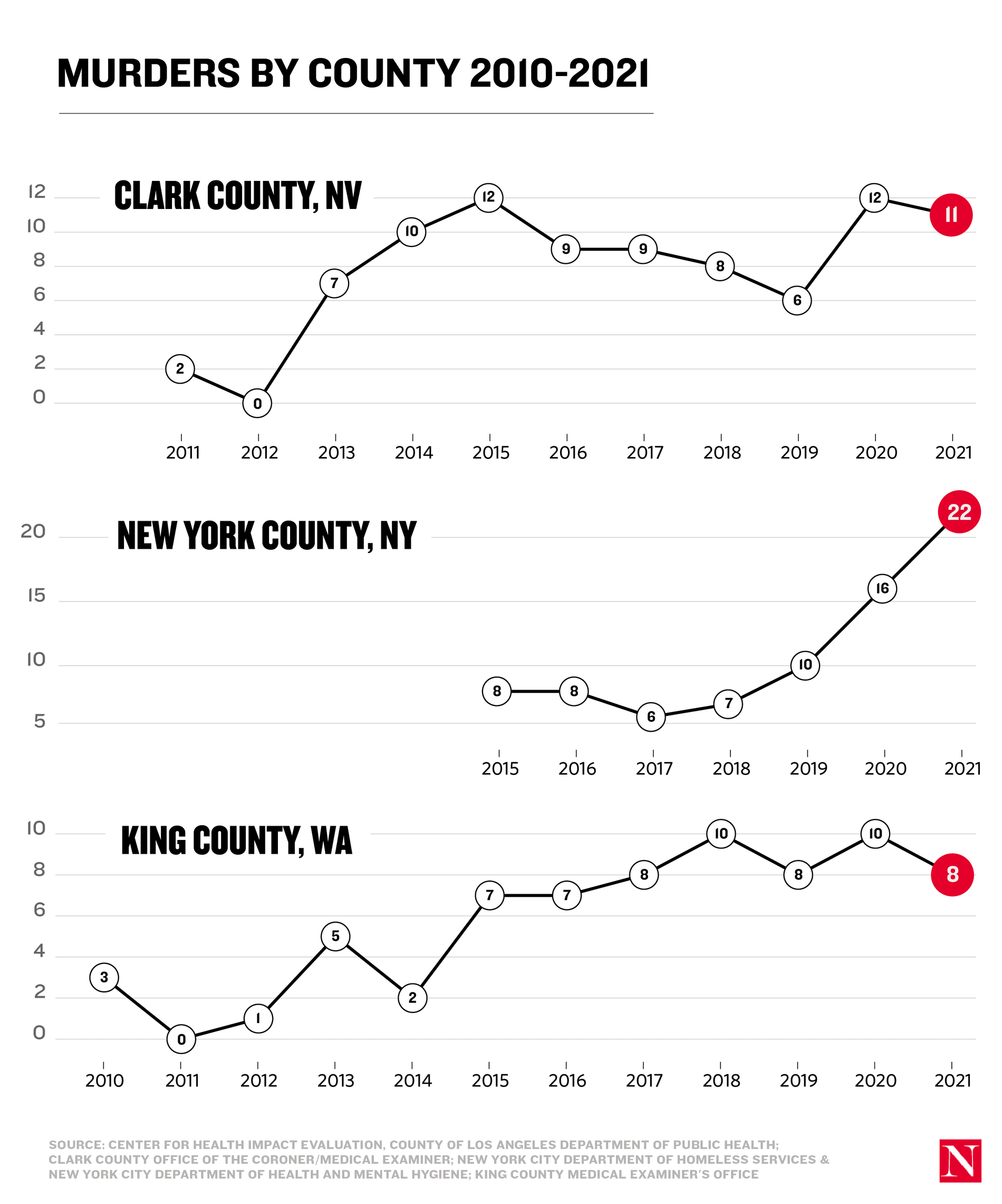

Murders of unhoused people in the United States have been on the rise, raising alarm about the ever-pressing urgency of our nation’s homelessness crisis. Examining mortality data for 17 US jurisdictions, Matt Fowle and Fredianne Gray of HomelessDeathsCount.org find 1,285 killings of homeless people since 2010. That’s both a fraction of the true national homeless homicide total, which is unknown, and the most violent and unlawful subset of 26,978 overall homeless deaths from all causes in those cities.

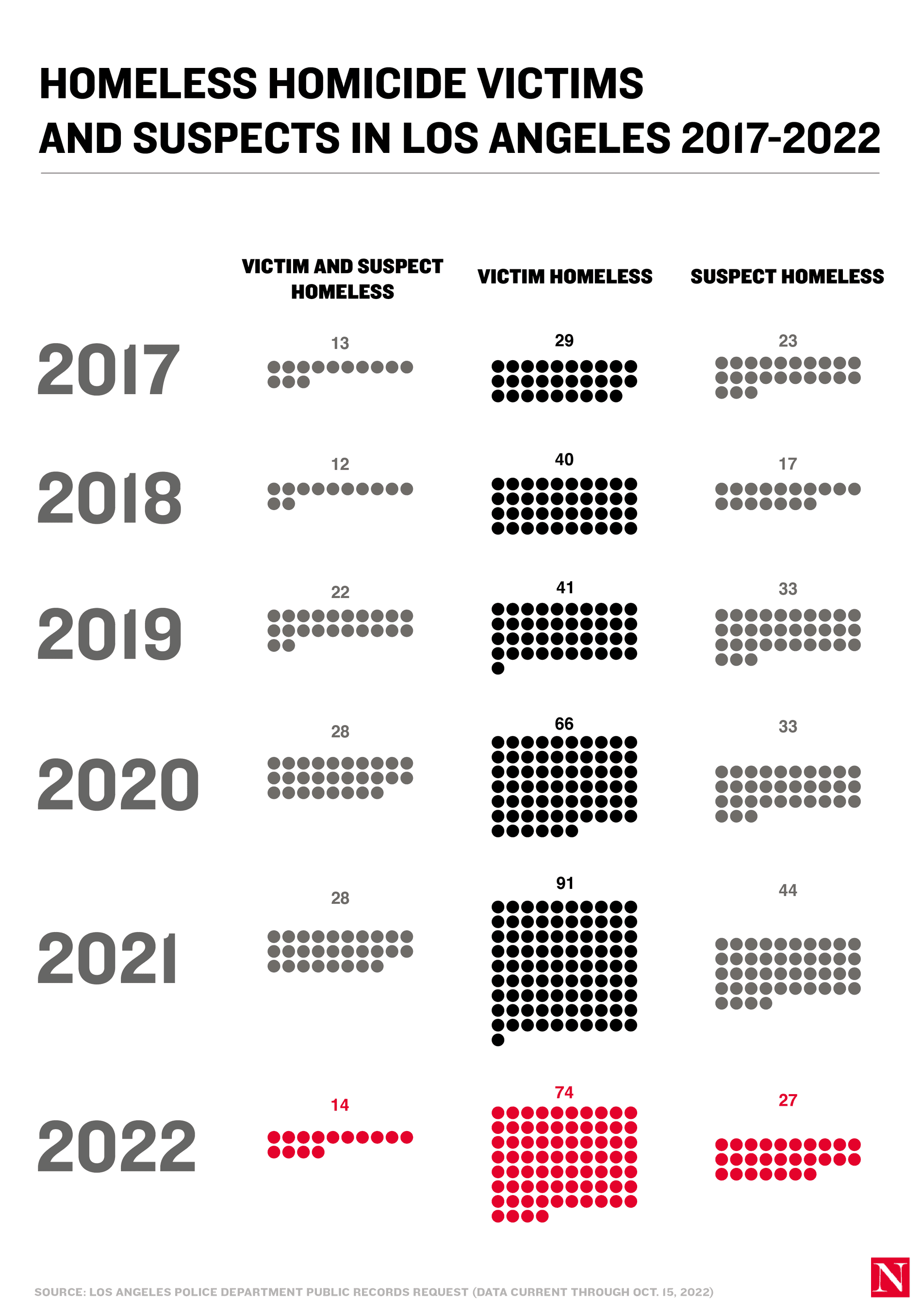

Los Angeles Police Department data shows the rate of homeless homicides has ramped up this decade—the total for this decade’s three years exceeds all of last decade’s—and experts say violence against homeless people is surging nationally. LAPD data shows that unhoused people are two or three times as likely to be victims as suspects—and if we remove homeless-on-homeless homicides to focus on “stranger danger” cases, the ratio is three to one.

Experts say this is what happens when housing unaffordability and compassion fatigue towards people experiencing homelessness meet an historic national surge in gun deaths. At least a dozen cities saw record homicide totals in 2021.

“You have an epidemic of homelessness and living outside, and an epidemic of gun violence,” says Barbara DiPietro, senior policy director for the National Health Care for the Homeless Council. “No one should be surprised to see that this is increasing. We throw vulnerable people to the wolves every day.”

The trend is complex because it brings together two issues—homelessness and homicides—that are polarized battlegrounds. Over all, the rise in homeless homicides over the last decade likely reflects a growing US homeless population that experts say may be as high as it’s been since Great Depression shantytowns. (Federal agencies including HUD and the Department of Education have different methodologies and totals for the number of unhoused people in the country; the true total of unhoused people in the nation is unknown, but likely far higher than HUD’s tallies.)

Interactive map of homeless homicides by county:

More recently, the spike in homicides of homeless people this decade appears to be related to the pandemic. Brian Davis, director of Grassroots Organizing at the National Coalition for the Homeless, says Covid-19 left people like Coughtry and Lewnes facing a “horrible choice” between mean streets and packed shelters.

“Do you risk your life on the streets,” Davis asks, “or in a room with 50 or 400 other people?”

In March 2020, Lewnes posted on Facebook, “They say not to be around groups of 10 or more. I know, let’s cram everybody into a shelter. Wtf. The safest places are parks with lots of trees.”

In a 2020 report, Davis’s coalition found a statistical correlation between the 2007–08 Great Recession and cresting anti-homeless violence. It’s happening again, pushed by economic jolts like inflation.

Nationally, mental illness is also on the rise, and is likely connected to rising violence against unhoused people. (Portland, for example, is breaking homicide records, including homeless people; Oregon is near the bottom in state mental health rankings.)

“People are more depressed; they’re more worried,” DiPietro says. “A nation on edge is going to have more murders.”

After a 2020–1 halt in encampment sweeps based on CDC guidance coincided with a “significant decline in attacks” on unhoused people, Davis says, encampment sites are now being swept in 66 US cities.

Such actions often occur in partnership with law enforcement, which for DiPietro highlights a tension. How, she wonders, can police be two things: both pulling down tents and investigating homeless people’s deaths?

“If you dehumanize people, how is it that you take their deaths seriously?” she asks.

There is a scarcity of data on homelessness amongst law enforcement agencies. That is changing, but not fast enough. The George Floyd Justice in Policing Act (stalled in Congress) calls for the collection of “housing status” linked to law enforcement use of force. The state of California passed an act in 2015 requiring law enforcement stop data for persons “perceived to be unhoused,” but it’s not clear how widely the data is being gathered amidst pushback. A recent federal research grant to look at law enforcement homeless data, a Dept. of Justice spokesperson clarifies, will merely “guide further research.”

Homeless mortality data from medical examiners and health departments, meanwhile, uses different methodologies and can be slow in coming. A spokesperson for Multnomah County, Oregon, which includes Portland, for example, emailed me in March of 2022 that 2021 mortality data would “be finalized” last summer. It was released February 15, and more than doubled the total from the previous year, when Coughtry and Lewnes were killed.

An Associated Press investigation found that at police departments in large cities with big homeless populations, including New York City, Los Angeles, Portland, and Washington, none except Los Angeles could share data on homelessness without a records request and long wait. When I emailed the NYPD for data in September, an anonymous response noted, “Please be referred to FOIL,” with a response due February 3, but which had not arrived by February 15.

The LAPD appears to be unique nationally amongst big cities: it actively tracks homelessness, which it offers in searchable form on the city’s open data portal, has a high-ranking “homeless coordinator” and a quicker turnaround for records. As of November 22, its data show 341 “homeless homicides” (237 victims and 104 suspects) since 2020, which is more than the previous decade’s 275 total (169 victims and 106 suspects).

Another exception is Oregon. In a new law that appears to be the first of its kind, the state is tracking homeless mortality, including homicides, beginning last year.

“There needs to be some standard,” Davis says. “Every community should be reporting this information.”

As homeless homicides increase, so do uncomfortable questions.

Why, for example, are there five or six times as many reported for Los Angeles as for New York, even though the latter city’s homeless population is the largest in the nation? Is it because New York City has a “right to shelter” law so its homeless population is 95 percent sheltered, while 70 percent of unhoused people in Los Angeles are unsheltered, i.e. living in tents, cars or other places not meant for human habitation?

The role of shelters in creating safety is important, but not simple. DiPietro recalls a homeless man in Baltimore telling her he slept on a porch with a camera because “if someone kills me at night, maybe you’ll catch it on tape.” Unhoused people frequently “rotate” between shelters and the streets, she says, while Davis adds that while one is less likely to be “jumped or robbed or killed” in a shelter, there are “other risks,” like airborne infectious diseases.

As The Nation has reported, homelessness is changing: 2020 was the first time that the official “Point in Time” homeless count report to Congress documented a majority living unsheltered. Vehicle residents comprise the fastest-growing, and perhaps most-misunderstood, subpopulation—a group Coughtry and Lewnes were a part of before their deaths.

Another question concerns the media: why does it disproportionately focus on homicides in which a homeless person kills a housed person, like Michelle Go in New York or Sandra Shells in Los Angeles, rather than the statistical majority? Such killings are often a comparatively small percentage of the whole: in Los Angeles, for example, LAPD records show they were 177 of 635 homeless homicides from January 1, 2017 to October 15, 2022—about a quarter—while an earlier LAPD records release found the percentage to be even smaller, about 15 percent.

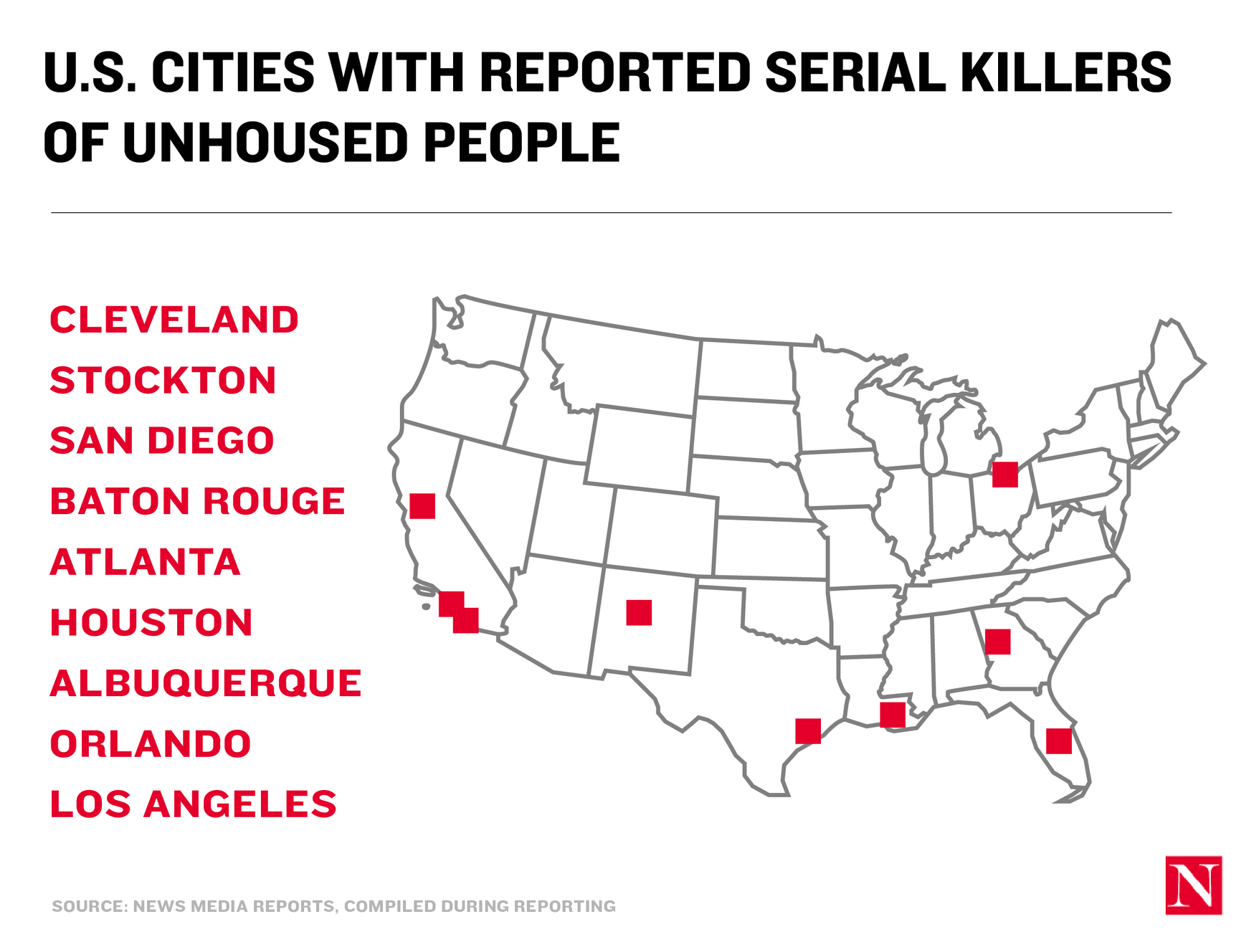

And why are so many serial killers preying upon unhoused people? Since 2010, they’ve popped up in San Diego, Baton Rouge, Atlanta, Houston, Albuquerque, Orlando, Los Angeles, Stockton and probably other cities.

DiPietro points to the nexus of our hyperviolent culture and the dehumanization brought by criminalizing homelessness.

“We have a ubiquitousness of violence generally, and as we criminalize homeless people we gradually reduce their humanity,” she says. “It’s easier to be violent to someone who’s [seen as] not fully human.”

Last year the nation’s attention turned to Gerald Brevard III, who allegedly killed sleeping homeless people in NYC and DC, then posted on Instagram, “feeling devilish… feeling godly.” There was also the Miami real estate agent, Willy Maceo, who allegedly pulled his Charger alongside sleeping humans and shot them. Such horrors are why Davis’s coalition and others have long advocated for homeless homicides to be considered as potential “hate” or “bias” crimes. Currently Maryland, Rhode Island, Florida, and a few other US jurisdictions define violence against unhoused people this way, but some say such laws are often “forgotten.”

“If your city starts turning its back on people experiencing homelessness, it seems to give a license to people who are on the fringe and may have other issues,” Davis says.

For grieving friends and family, the most important question is: how many of these murders are solved? The answer’s unavailable, Davis says—often marginalized, like those it describes. Only about half of all homicides are now solved, so the rate for those with no fixed address is almost certainly a minority.

It’s also far from clear that more funding or staff for law enforcement will help, when the role of police officers and sheriff’s deputies in investigating murders of unhoused folks is undercut by their frequent assistance in the tearing down of encampments, towing of vehicles, or locking up people who must exist in public space for charges like loitering, trespassing, or drug possession.

Back at Force Lake late last year, a couple residing in a Scion XB told me their car had just been egged. Bushnell has talked to homeless people there, too, and heard rumors, but she’s trusting the police to solve this. Her experience with Detective Rico Beniga and others has been “really good,” she says, but “some things are harder to solve than others.” So, she grieves in private, and shares pickles with Coughtry’s daughter, who also loves them.

“Will it ever come to closure?” she asks. “ I don’t know. I hope it does.”