EDITOR’S NOTE: The Nation believes that helping readers stay informed about the impact of the coronavirus crisis is a form of public service. For that reason, this article, and all of our coronavirus coverage, is now free. Please subscribe to support our writers and staff, and stay healthy.

The Nation and Magnum Foundation are partnering on a visual chronicle of untold stories as the coronavirus continues to spread across the United States and the rest of the world. Each week we’re focusing on and amplifying the experiences of frontline workers and communities disproportionately affected by the upheaval, all through the independent lens of image makers whose role in recording, collecting, and communicating stories is especially crucial in a time of collective isolation.

This week, photographer Cinthya Santos Briones reached out to friends from Mexican and K’iche’ migrant communities to check in and ask how they’re weathering the crisis. “As we continued to chat,” Santos Briones says, “I realized there was incredible value in the stories surfacing from their updates.”

What resulted from these exchanges was a series of images documenting how some of the most vulnerable communities are seeing and experiencing this crisis. “For these migrants, staying home is not an option,” Santos Briones explained. “This pandemic represents one more crisis that they have to bear in their lives. Some have been fired from their jobs, others continue to work in restaurants, in grocery stores, in factories, and cleaning houses.”

“Typically a photographer, my role became more curatorial,” Santos Briones says, “to amplify the gaze of babysitters, domestic workers, cooks, waiters, delivery people, and day laborers—perspectives that aren’t often published in the media.”

What follows are photos sent to Cinthya, along with snippets of the conversations she’s been having over text messages over the past several weeks.

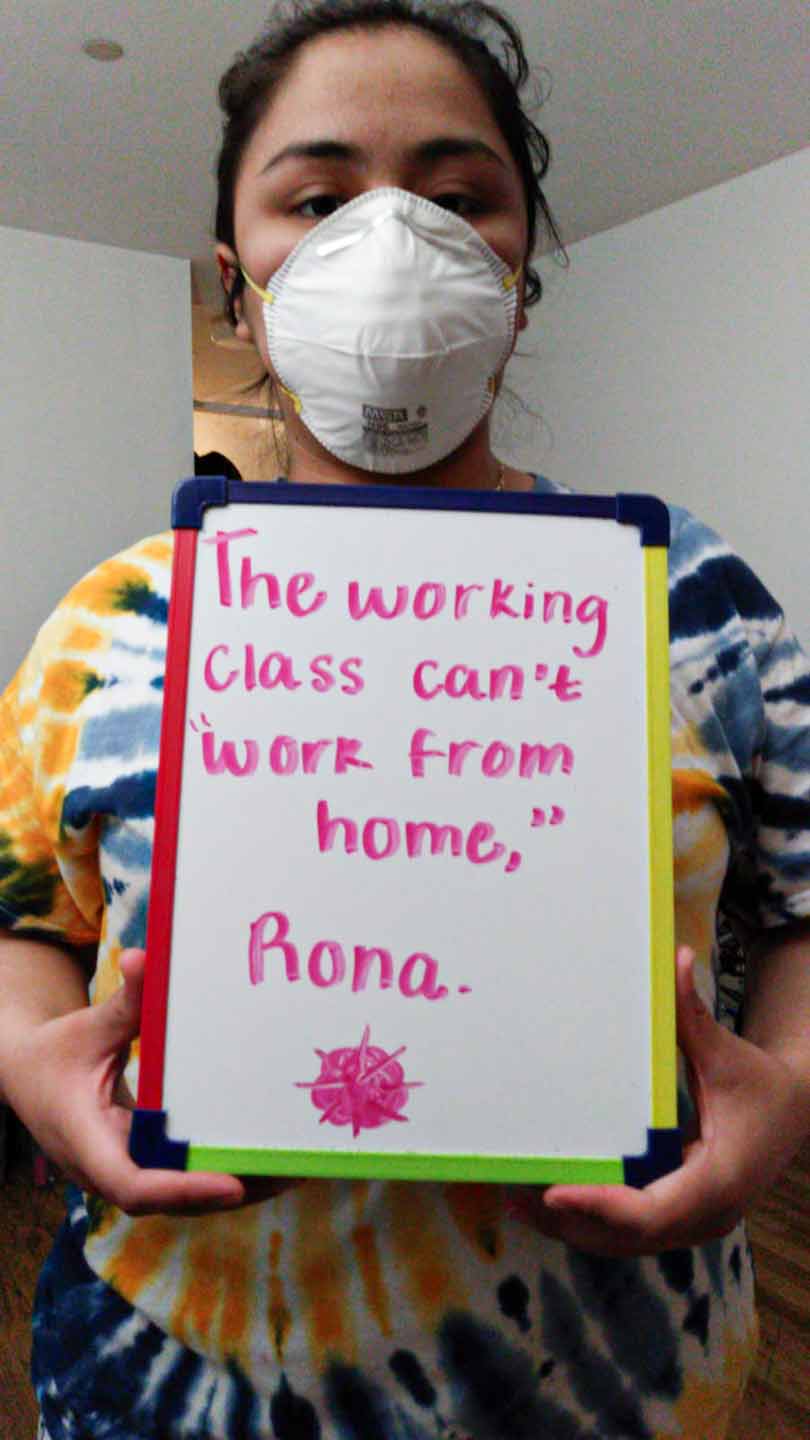

Heidy Animas: “We as working class migrants cannot give ourselves the privilege of not working, we have to pay the rent, the bills. And although I was born here, my parents are immigrants.”

Cinthya: Are you still working?

Kimberly: During this pandemic I have had to do different jobs, one of them was working in a factory bottling hand sanitizer at 62nd St and 13th Avenue in Brooklyn. In the factory my job is to put the hand sanitizer in the empty bottles. Then other workers are in charge of putting the red caps on, cleaning the bottles, putting a sticker, and packing them. My bosses pay me per day $100 from 9 a.m. until 6 p.m., with a half an hour break.

Cinthya: Hello Kimberly! How is your life at this moment of the coronavirus?

Kimberly: Hi Cinthya, right now it’s a little difficult, with the kids at home, everyone already is at home. There is no space for everyone to be in their own space. My family and I live in a room with 5 people, it is difficult for us not to fight. Each thing makes us angry, of course we have our moments that we laugh but, with so much being together, at times we feel we will suffocate. You already get bored of being the same every day. Now, if you go out, you already have to use gloves 🧤 and a mask 😷.

Cinthya: Good afternoon dear Aracely, how have you been during these days of coronavirus?

Aracely: Well, with God’s protection I am fine. I’m with my husband at home and we make Mexican hot dogs and instead of tomato sauce we use chipotle.

We live in New Jersey, my husband works in a meatpacking company every day from 8 a.m. to 5 p.m. Other workers work from 3 a.m. to 1 p.m. and usually after work we try to eat together, walk out and see the trees.

Cinthya: Hi Myrna, how have you been?

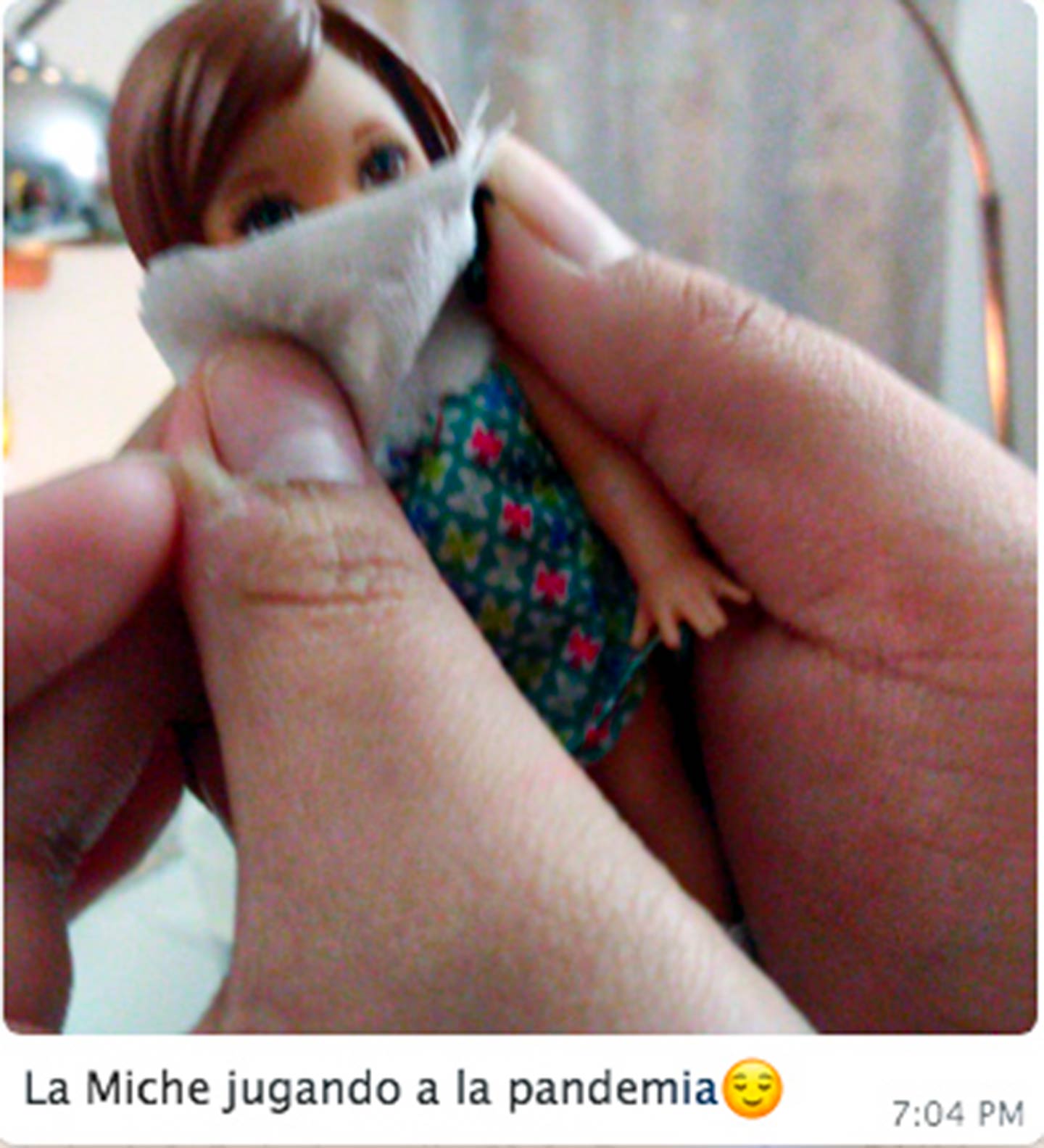

Myrna: Good, Michelle plays a lot during the pandemic. In order for my daughter not to get bored from the confinement, Michelle and I have made clothes for her dolls. She wanted to make a face mask for her Barbie.

Cinthya: Dear Francisca, how are you?

Francisca: Hi Cinthya. With good health thanks to God.

Cinthya: Are you still working?

Francisca: I’m still working, but I would rather stay at home, but I can’t because we need to buy things to eat and pay the expenses that we have. When I go to work, I don’t get close to people. In fact I walk to work to minimize the risks of being infected.

Walking towards my work I passed by “la parada,” one of the places where migrants wait to be picked up for work [in Brooklyn]. I see a lot of worry on their faces, immigrants are afraid of losing their jobs in this pandemic.

Cinthya: Hi Jesus, what did you do today?

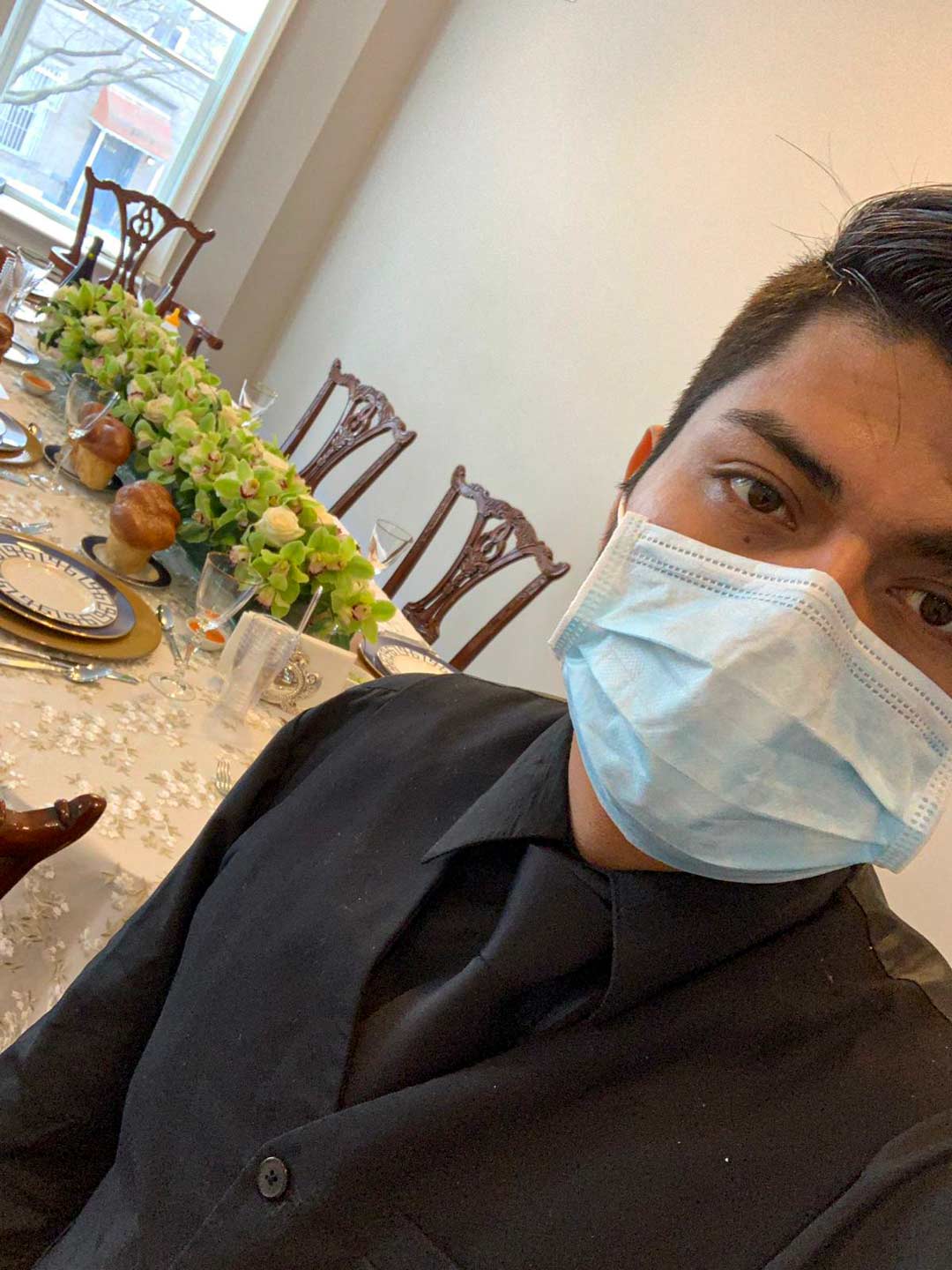

Jesús: I was working and my bosses asked me to wear a mask. Usually I work as a waiter or in construction. Despite this pandemic, from time to time, I have had work, but not like before.

Cinthya: How are you Jesus? How have you been with the Coronavirus?

Jesús: Hi Cinthya, for the moment I am well, resting at home, since due to the situation we are experiencing I have not been able to work. The job where I was working in construction is closed until further notice, but hopefully this situation will be resolved soon, since, financially it is affecting me.

Myrna Lazcano: We bleach [the masks] and reuse them because they cost $3.

Kimberly: Hi Cinthya, how are you? today I went to the “marqueta” on Fifth Avenue in Sunset Park. The stores no longer let you be in crowds, they put signs warning us to take care so that we do not get infected with the virus. People walk around with masks and gloves on.

Myrna Lazcano: We do gather between friends and family to endure this crisis as we play the lottery and eat together. Although we do not have much space and we know that we are in a crisis, we, as migrants, always know how to get out of hard times.

Cinthya: Hi, what are you doing?

Myrna: Miguel and I are dancing to Boleros songs by Mexican singer Javier Solis in the living room.