Trauma’s New Look

Internal Family Systems is the latest therapy trend for a traumatized United States. But can splitting ourselves into parts be a science?

The Rapid and Dubious Rise of the Internet’s New Favorite Therapy

Internal Family Systems has been wholeheartedly embraced by celebrities and desperate patients alike. But is it a science—or a scam?

It was around 35 minutes into my conversation with Dr. Richard Schwartz that our interview turned into a therapy session. We had been discussing internal family systems, or IFS, the therapeutic modality he founded in the 1980s, when I mentioned that I was skeptical of the approach. Unperturbed, Schwartz responded by asking me to home in on that skepticism; he suggested I try to find it in my body.

“I think it’s in my left abdomen,” I offered, although I feel everything there these days, thanks to a recent surgery.

“All right,” he said, addressing my abdomen. “So, are you there? Are you willing to talk to me as the skeptical part of Jessica?” Then, shifting his attention back to me, he added, “Focus down there, and let it know you’re curious about it and why it’s so skeptical, and just wait for the answer to come. Don’t think.”

I tried to focus on the lower left quadrant of my torso, to wait for it to offer up an answer, but my mind kept interrupting with thoughts like “Is he waiting for me to reveal something profound?” and “Why does my face feel hot?” After a few failed moments, Schwartz suggested we change our approach.

“Ask it this question: What is it afraid would happen if it wasn’t so skeptical? See how it reacts to being appreciated.”

His voice was calm as he said these words—a mix of gravelly and nasal, like a meditative teddy bear; his eyes were encouraging. But once again, I struggled to focus. Behind his head, I noticed a piece of black-and-yellow modern art that read: “It’s never too late to come home to your Self.”

In trying to get me to home in on my skepticism—or what he would call my skeptical “part”—Schwartz was practicing one of the fundamental techniques of IFS therapy, which is to locate specific feelings within the physical body. Through this technique, IFS promises to “heal trauma” and “restore wholeness,” while also helping to treat more discernible diseases like addiction and depression. In his 1995 book Internal Family Systems Therapy, Schwartz describes IFS as “a synthesis of two paradigms: the plural mind, or the idea that we all contain many different parts, and systems thinking”—but a more apt description might be that IFS is a combination of Jung, Freud, shamanism, Yogic theory, and Gestalt therapy, all jumbled together and simplified to make it as marketable as possible. Occasionally, Schwartz explicitly taps into other traditions. “In Buddhist terms,” he writes, “IFS helps people become bodhisattvas of their psyches in the sense of helping each inner sentient being (part) become enlightened through compassion and love.”

While IFS remained something of a niche therapy for much of its existence, it has, in recent years, gained enormous popularity on Instagram and TikTok and with celebrities ranging from the musician Alanis Morissette to Queer Eye’s Jonathan Van Ness. (“The whole parts thing is really ferosh,” Van Ness writes in his 2019 memoir, Over the Top.) Schwartz, who runs programming at one of Harvard University’s teaching hospitals, has himself become a sought-after guest speaker at “healing retreats” around the world, and his books, You Are the One You’ve Been Waiting For (2018) and No Bad Parts (2021), have become bestsellers. When I reached out for an interview last fall, I was initially told I would have to wait until the third or fourth quarter of 2025.

At the same time, the IFS Institute, the for-profit organization Schwartz founded in 2000 that’s responsible for educating budding IFS therapists and “trainers,” has been growing rapidly. In recent years, its staff has expanded from 12 to 35, according to Schwartz, and it says it trains nearly 4,000 providers a year—a significant jump from 2020, when it trained roughly 1,600 providers, and from 2017, when it trained just 500. The IFS Institute has also taken part in retreats and trainings in places like Costa Rica, Spain, and Germany, where the activities can include guided meditation, “unburdened eating,” and strolls on the beach. IFS has also become a popular “complement” to psychedelic therapy.

All of this jibes with my own experience. For the past decade, I’ve been reporting on healthcare in New Zealand and the United States. During much of that time, the acronym “IFS”rarely crossed my radar. But at some point in the past few years, sources and acquaintances began mentioning IFS, sometimes in an offhand way, sometimes because they themselves were seeing an IFS specialist. As I combed through therapist directories for my research, I noticed they were suddenly littered with bios boasting IFS expertise. One investigation of IFS, from April 2024, found that 45,764 psychotherapists on PsychologyToday.com mentioned using the treatment. “I’ve been at this for over 40 years, much of it in relative obscurity, so it’s a bit of a dream come true,” Schwartz said of his therapy’s newfound popularity. I wanted to find out why.

In the long and colorful annals of psychotherapy, IFS is hardly the quirkiest approach out there—this is, after all, the profession that gave us the Oedipus complex. But IFS is also decidedly more ethereal than many recent interventions, which tend to eschew the old intrapsychic models of treatment in favor of a more sober, just-the-facts approach.

The story of how Schwartz, who is 75, came up with IFS begins in the early 1980s, not long after he graduated from Purdue University with a PhD in marriage and family therapy, a traditional form of psychotherapy that came out of the family systems model. Family therapy posits that you cannot understand someone in isolation, as an individual; that focusing on the inner mind is pointless because we are determined by our familial relationships. It typically consists of sessions where all members of the family discuss the issues of the patient together.

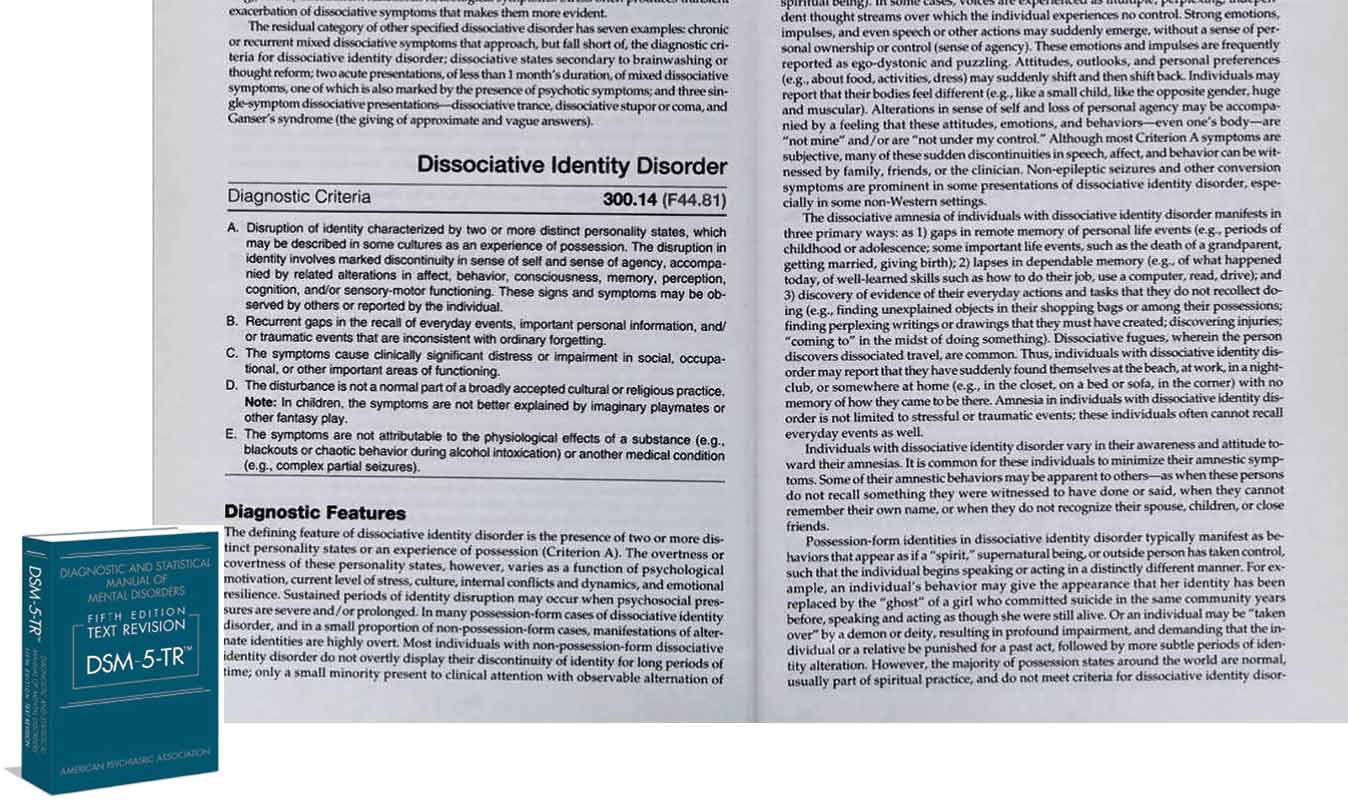

Around 1981, Schwartz tried to “prove family therapy’s healing power” with a population of young bulimics, believing he could cure them by changing the dynamics of their familial relationships. But the outcome didn’t confirm his hypothesis. Out of frustration, Schwartz often recounts, he asked his patients why nothing was changing. “They would talk about how, when something bad happened in their lives, this ‘critic’ would attack them,” he told me during our interview. “That would go right to the heart of a ‘part’ that felt totally worthless and empty and lonely, and that feeling was so dreadful that the binge would come in to rescue them from that.” He thought he’d stumbled upon a mass case of what was then called “multiple personality disorder” (now known as “dissociative identity disorder”—a contested diagnosis itself), until he realized that he had different parts, or multiple personalities, too. So Schwartz created IFS.

The gist is that we are all born as a Self (the capital “S” is important), but as we suffer, our psyche splits into different “parts”—not metaphorical parts, but actual ones. In No Bad Parts, Schwartz is emphatic: “Parts are not imaginary products or symbols of your psyche; nor are they simply metaphors of deeper meaning.” As he elaborates elsewhere, these parts “are individuals who exist as an internal family within us—and the key to health and happiness is to honor, understand, and love every part.” The goal is to bring these parts into alignment to achieve “inner peace.”

In the service of this goal, Schwartz has created a vocabulary that providers and patients must use to navigate the world of IFS. “Burdens,” for example, are extreme beliefs and emotions created during a trauma or “attachment injury.” “Exiles” are the hidden parts of someone’s personality that hold on to those burdens. To combat “exiles,” we have “managers” working hard to keep these negative feelings away by overachieving or not letting anyone close enough to hurt us. And then, because exiles do get triggered, there are “firefighters” to ease the pain.

Some patients swear by the transformative power of this cosmology. “After taking this IFS Self-healing journey with my parts,” one patient turned provider writes on her website, “I found my true Self—someone who can show up for me like a hero. Someone who champions my right to be free, spontaneous, seen, cared for, loved, cherished, enjoyed just as I am.” For such devotees, IFS offers nothing less than a path to self-empowerment, self-love, and, crucially, through its emphasis on “no bad parts,” freedom from shame. It also offers an encompassing, at times even spiritual worldview—or as the patient turned provider writes, IFS is simultaneously a “psychotherapeutic approach, a working model of the mind, and a lifestyle.”

Amid this exuberance, however, some have sounded a note of caution. In an article in the Psychotherapy Bulletin, the researchers Lisa M. Brownstone, Madeline J. Hunsiker, and Amanda K. Greene write that “the current expansion of IFS across psychotherapy and social media has moved beyond its evidence base.” The authors note that the existing research on IFS excludes people with psychotic symptoms, even as they warn, based on their own observations in clinical settings, of the “overapplication” of IFS to people with such symptoms: “Our concern is that encouraging splitting of the self into parts for those who struggle with reality testing might be disorganizing.”

The American Psychological Association has noted the rise of IFS. In an e-mailed statement, Lynn Bufka, the association’s head of practice, said, “APA recently adopted a new guideline on the treatment of PTSD, where scientists reviewed treatment research extensively. IFS was noted as one of the interventions that is currently being used, but is in need of much more research before they could make a recommendation about its effectiveness.”

Given that IFS has been around for decades, why is it only now hitting its stride? Schwartz attributes its surge in popularity to Inside Out, the 2015 animated Disney film in which emotions are personified as distinct characters (Anger, Joy, Sadness, Fear, and Disgust) inside a child’s mind. It’s the kind of explanation that feels at once underwhelming and astute—which is to say that Schwartz is right, though not, perhaps, for the reasons he thinks.

While the rise of IFS can’t simply be attributed to a movie that became a cultural touchpoint, Schwartz’s recognition of the way mass media and culture can shape the mental health landscape says a lot about modern-day therapy. In a world where everything is commodified, Inside Out has become a franchise—you can buy a Sadness plushie at Target—while therapy is now a billion-dollar industry, as private equity firms increasingly buy out behavioral health facilities, online therapy services spend millions on podcast advertisements, and social media consulting agencies target therapists. (“Invest in a social media strategy that will grow your private practice for the long-haul,” one ad reads.)

In this new mental health universe, therapies that lend themselves to branding have an upper hand. The most notorious example of someone who has taken advantage of this is Esther Perel, the host of the popular podcast Where Should We Begin?, on which Perel does ad reads between segments for books and vaginal health products. According to Awais Aftab, a professor of psychiatry at Case Western Reserve University, platforms like TikTok and Instagram could be playing a big role here: “IFS has the kind of quirky and mysterious vibes that seem perfectly designed for the TikTok and Instagram age,” Aftab told me via e-mail. “Which explains the fact that even though the modality is decades old, it didn’t get popular until recently.” In one TikTok video, a woman who practices IFS portrays “her exiled inner child” by wearing a tie-dyed shirt and sporting two side ponytails. Her “firefighter” personality wears heavy eyeliner, a beanie, and a mesh hoodie with skulls. In another video, a psychologist changes outfits when talking about “exiles”—suddenly, the suited-up woman is wearing a billowing dress and a puffy headband and looking up at the camera from below while holding a soft toy, as if she’s a little kid.

That might sound wacky, but it can be effective for some people. And while Schwartz and the IFS Institute almost certainly didn’t conscript TikTokers to do their PR, it’s clear that both he and the institute have done a good job of marketing IFS—in particular as a treatment for addiction, depression, and, notably, trauma.

In No Bad Parts, Schwartz leans head-on into the cultural obsession with trauma, flagging it prominently in the book’s subtitle: Healing Trauma and Restoring Wholeness With the Internal Family Systems Model. For Schwartz, the “attachment injury” that causes a “burden” can range from physical abuse to being humiliated in school. People then “carry these extreme beliefs and emotions that drive the way they operate almost like a virus,” Schwartz told me. As he writes in the book, “most of the syndromes that make up the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual are simply descriptions of the different clusters of protectors that dominate people after they’ve been traumatized”—a pretty bold claim.

Trauma, as a concept and a diagnosis, has become hot as of late. This is partly because it can serve as a catch-all in an era in which more and more people are comfortable talking about mental health. Everyone has suffered from something they can call a trauma, whether it’s having been bullied, experiencing the death of a family member, living through Covid-19, or worse. While more “serious” mental illnesses continue to carry a stigma in the broader culture, trauma has reached a certain level of acceptability. It can explain distressing or embarrassing mental symptoms without the baggage of a mood or personality disorder—and it is, by definition, the fault of an external factor or event. In other words, it’s not your fault.

Maria Fernanda-Wilbur, a New York City–based social worker I spoke with, confirmed a growing demand for treatments that address both “big T” and “little t” trauma, especially in the wake of Covid-19. You’ve probably seen or heard the T-word elsewhere, too, however. In recent years, trauma narratives have proliferated in novels and TV series—see Parul Sehgal’s essay “The Case Against the Trauma Plot” in The New Yorker—and social media has contributed to a working familiarity with the term, along with the previously cloistered “gaslighting” and “narcissism.” Another cultural influence has been the psychiatrist Bessel van der Kolk’s book The Body Keeps the Score, which attempts to make the case that trauma can fundamentally reshape the body and the brain. Published in 2014, it found a new wave of readers during the pandemic and has been on the New York Times bestseller list in the paperback nonfiction category for more than 334 weeks. Notably, van der Kolk effectively gives IFS his blessing in a chapter on the theory. “We all have parts,” he writes, adding, in words that could have been penned by Schwartz himself, that “a part is considered not just a passing emotional state or customary thought pattern, but a distinct mental system with its own history, abilities, needs, and worldview.” Several years later, van der Kolk went a step farther in a blurb he wrote for No Bad Parts: “IFS is one of the cornerstones of effective and lasting trauma therapy.”

Generally speaking, treatment of any kind is a good thing, but suggesting that everyone has trauma can also lead people to downplay the very real neurological and emotional effects of post-traumatic stress disorder. And if education about the diagnosis comes mainly from TikTok, people interacting with those who have PTSD won’t be prepared for the ways it can affect interpersonal dealings. “If everyone’s body is keeping the score,” Danielle Carr wrote in a profile of van der Kolk in New York magazine, “what that score actually adds up to starts to get less clear.”

If IFS has benefited from the rise of the trauma industry (and, more broadly, the phenomenon of therapy as a brand), it’s also gotten a boost because it meets a genuine need among an increasingly desperate public: for therapy that is affordable, accessible, and—for some, at least—effective.

Noah, who for the past two years has been seeing a therapist who uses IFS, turned to the modality because it was an alternative in a world of few successful treatments. “Using that sort of visual metaphor in combination with understanding parts,” he said, “makes it easier to come back to and listen to the concerns that my parts have.” He sees it as something much more substantial and therapeutic than “merely practicing ‘positive self-talk’ or the hollow, commodified versions of ‘self-care,’” he said.

Noah is not alone in feeling at a loss for effective options. This is a much larger issue, especially as the cost of mental healthcare in the United States continues to climb. Until last year, the IFS Institute offered training to unlicensed mental health workers, attracting a large number of uncertified “trainers” and life coaches. Besides the cost of treatment, the conundrum for people diagnosed with trauma is that they are often told that their needs are “complex” and thus can’t be met by just anyone.

One of the main treatments for diagnoses that involve trauma is dialectical behavioral therapy, or DBT. It’s considered most effective when patients engage in individual sessions that last around 90 minutes as well as weekly group sessions. Most insurance companies, however, only reimburse for 45 minutes of DBT, meaning that this has become the de facto length for a therapy session. Some plans also limit the number of sessions they cover under the guise of “medical necessity.” In New York City, it’s not uncommon for therapists who specialize in DBT to charge $300 to $400 per session. Another common treatment for trauma is exposure response prevention (ERP) therapy, which requires specific training and is meant to rewire the traumatized brain to give up its love for hypervigilance and avoidance. Yet DBT and ERP can both be difficult to get covered by insurance. In fact, according to a 2024 report from the American Psychological Association, one-third of psychologists don’t take insurance for any kind of therapy.

In a world where rent is increasing rapidly, as are the prices for basic necessities like groceries and transportation, therapy is often seen as a luxury. This gap in the accessibility of treatment—for trauma, depression, addiction, and other mental health diagnoses—is where IFS-trained therapists or counselors have been able to gain a foothold.

As the demand for IFS therapists has grown, the IFS Institute, like any good business, has worked hard to expand the supply. In addition to increasing its full-time staff to 35, the institute has expanded its army of trainers from 30 to more than 100, although it claims that it still doesn’t have enough. At the time of my reporting, there was a waiting list of some 20,000 prospective IFS therapists interested in learning the secrets of the trade. “We’re working really hard to try and meet the demand,” Schwartz said, “and it’s really hard.”

The IFS Institute offers three levels of certification for would-be practitioners. The most basic is Level One, which in the United States costs $3,990 to $5,300 and consists of roughly 100 training hours. The more expensive courses might include accommodations at beautiful remote locations, such as the Ghost Ranch in New Mexico, where visitors can take a tour of the landscapes that inspired Georgia O’Keeffe or relax in a “lotus sound bath” between sessions. Level One grants therapists a spot in the IFS Institute Practitioner Directory and the right to “refer to yourself as IFS Trained” (not “certified,” but what patient would know the difference?). Level Two training ranges from $2,550 to $2,950 per course. Level Three, which is advertised as “continuing education,” costs between $2,700 and $2,900. All told, getting to Level Three will set an aspirant back nearly $10,000 at a minimum.

To advertise as “IFS-certified”—which, again, does not necessarily mean being a licensed therapist—practitioners need to have completed the Level One and Level Two IFS training programs, or a Level One training and then a stint as a Level One “Program Assistant.” There are a number of other requirements, too, the final one being that applicants must submit a 45-to-60-minute video of themselves doing an IFS session or schedule time with a reviewer to join a live session. There is, naturally, a $200 review fee for the video sessions on top of the $200 certification fee—money that all goes to the IFS Institute run by Schwartz.

Therapists are required to recertify every two years, for a fee of $150, and to earn 20 credit hours of IFS continuing education. There are various ways to earn these credits, including by taking courses ($245, for example, pays for 14 credits via a number of on-demand videos that highlight a specific IFS skill) or by going to the IFS annual conference. Once a therapist is certified, the two-year recertification requirement guarantees a career-long source of income for the institute.

IFS finds itself at an interesting moment, one that, because of the popularity of therapy and its position as a fast-growing industry, allows therapists, life coaches, and others to market themselves as professionals offering a service. IFS’s increasing popularity has also attracted posers who seek to capitalize on the somewhat nebulous professional status of its practitioners. Now, not only do actual certified IFS trainers market their services, but also an offshoot world of purveyors who ply their trade via social media accounts and who claim to practice IFS but are not affiliated with the institute. (Schwartz looked into trademarking IFS, he said, but was told that it was in the public domain now.)

“There are lots of copycats that are popping up,” Schwartz said, “and people who don’t really know the model that well are teaching it and making a lot of money.” The copycats include a man named Sasha Eslami, who advertises himself as a Level Three IFS practitioner. (The IFS Institute, when asked, said he is not affiliated with it.) Eslami offers an “Inner Circle” membership plan for $790 a year and runs an app called IFS Guide that lets you “talk to AI like a real IFS practitioner.”

Despite his inability to copyright IFS, Schwartz seems to be doing just fine. In January, he cohosted a ketamine and IFS crossover retreat in California for $8,500 per person. The “theradelic” retreat, set among tall pine trees, bubbling creeks, and an infinity pool, was targeted at “business leaders” in technology, entertainment, healthcare, and the psychedelics industry. In February, Schwartz was in Costa Rica, joining another psychologist for a week-long seminar on “trauma and releasing personal and legacy burdens.” In another retreat in Costa Rica, he spent a week leading practitioners through the core tenets of IFS for $7,000 (not including accommodations) with Alanis Morissette, who was introduced to IFS when she was seeking help for a second bout of postpartum depression. “I was buoyed by the idea of returning to our birthright of wholeness,” Morissette writes in the foreword to No Bad Parts, “through offering attention and care to each ‘part’ of myself as it adorably, horrifyingly, ceaselessly, and sometimes painfully presented itself.”

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →IFS is not unlike a pyramid scheme, in that once you are an official trainer, you can cash in by training new recruits. Frank Anderson, a psychiatrist, psychotherapist, and lead trainer at the IFS Institute, has spoken at multiple recent events, including a five-day retreat on IFS and complex PTSD in Killarney, Ireland. A typical blurb for one of the boutique IFS retreats hosted by Alexia Rothman, a clinical psychologist and IFS-trained therapist, reads, “The Sedona Mago Retreat center offers an exquisite landscape, waterfalls, garden walks, and healthful pesco-vegetarian cuisine.”

Some retreats are even offered to patients, provided they have a decent-paying job (or come from inherited wealth). The Rio Retreat Center in Arizona offers five-day PARTS (Personal Awareness & Recovery Through Self) workshops for nearly $4,000. The participants “focus on processing each of their ‘parts’ in order to return balance and harmony to the SELF.” The cost, which can be submitted to insurance for an attempt at reimbursement, covers meals and access to a “Brain Center,” which has equipment such as a “Chi Machine.” Lodging is an extra $700.

In making its sales pitch to both patients and providers, the IFS Institute consistently promotes its model as “evidence-based psychotherapy.” The reality, however, is that while the popularity of the treatment has increased over the past 40 years, the evidence of its efficacy has not.

The institute’s website lists nine links under its research section, which Schwartz directed me to when I asked him about clinical evidence during our Zoom interview. Three of the links are to pilot or proof-of-concept studies, while three are not to studies at all but to glossary explanations of IFS terms. One link is to a study about MDMA and PTSD in which therapists were allowed to use IFS if they wanted. The remaining two links are to small studies: One is a study of 53 people with Internet addiction, and the other—the most compelling one—is a study of 79 people with rheumatoid arthritis, 39 of whom had IFS therapy. The results are mixed.

One of the pilot studies, published in the Journal of Marital and Family Therapy in 2016, looked at IFS as an alternative to antidepressants, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), and interpersonal psychotherapy for “depressed female college students.” This was the second study ever to evaluate the efficacy of IFS. Among the criteria for the 37 participants was that none could have an official diagnosis of a psychiatric disorder, symptoms of PTSD, an eating disorder, a previous suicide attempt, or any current thoughts of suicide—all typical symptoms of serious depression. Even among such a limited subject pool, the conclusion was that, while there was a decline in depressive symptoms, there was no significant difference between the effects of IFS and those of the other treatments.

The study that initially gave credibility to IFS was the proof-of-concept trial exploring how the treatment would affect people with rheumatoid arthritis, both physically and mentally. That study, published in the Journal of Rheumatology in 2013, was the first randomized controlled trial to assess the efficacy of IFS on patient outcomes. Schwartz recalls the cohort as being a group of mothers in Boston. “We had the IFS group focus on their pain, get curious about it, and ask it the kinds of questions that we normally ask parts,” Schwartz writes in No Bad Parts. “The participants were mainly Irish Catholic women who’d never been in therapy before and had active caretaking parts that wouldn’t let them take care of themselves. As they listened to the pain in their joints, the parts that were using that pain began to answer their questions with answers like, ‘You never take care of yourself,’ and ‘We’re going to cripple you so you can’t keep doing this,’ and ‘We’re going to keep doing this until you listen to us.’”

Schwartz’s account is meant to sound like a narrative of liberation and self-discovery; read in another light, though, it sounds a lot like he’s blaming the patients for their physical pain, which, in reality, was caused by a chronic disease in which the body’s immune system attacks its tissue and causes inflammation. And while the researchers did find that those who had IFS therapy saw a reduction in physical pain, “there were no sustained improvements in anxiety, self-advocacy, or disease advocacy.”

Studying mental health treatments can admittedly be tricky: It’s an area that is subject to genetic and historical nuances that are hard to verify or ethically reproduce—which is why, when dozens of studies came out that praised the short-term efficacy of CBT, the therapy became something of a gold standard for a time. But this hasn’t stopped the trauma industry from slapping the words “evidence-based” onto everything as if it were extra virgin olive oil.

In 2014, when The Body Keeps the Score was published, Leah Benson, a Florida-based psychotherapist, was excited. “It meant there was finally some science backing up the methods I was using in a world where cognitive behavioral therapy was touted as the only legitimate therapy,” she told me. Benson preordered a copy and told all her colleagues about it. But years later, she realized that the book encouraged people to become overly focused on trauma narratives—and not in a good way. Now she has clients asking to “heal” or “release” their trauma. “They don’t really have any idea what that means,” she said. “Which isn’t their fault. Because it doesn’t really mean anything, except that they’ve been indoctrinated into pop-therapy language.”

Regarding IFS, Benson feels that the treatment is a particularly apt match for the diagnosis, given that people who traffic in its ideas have always spoken metaphorically. “It’s pretty obvious that every one of us are full of contradictory ways of understanding ourselves and the world. The designation of ‘evidence-based’ is a cloak for the insidious damage that can occur to the minds of vulnerable patients.”

Schwartz told me that it took 40 years for people to stop looking down on his ideas. But in his zeal to be accepted by the psychology establishment, he swept some of the more dubious aspects of IFS under the rug. Take the concept of “unattached burdens” or “demons,” which are explored in a recent book called The Others Within Us by Robert Falconer, who previously coauthored a book with Schwartz. Unattached burdens are considered negative parts (but not “parts,” mind you) of a person that aren’t attached to any body part: They can be suicidality, homicidal impulses, and so on. In the foreword to The Others Within Us, Schwartz, oddly, writes that he is hesitant to reveal what he thinks about unattached burdens: “IFS has reached a huge level of popularity and acceptance not only in psychotherapy, but in many other areas. Why revive that skepticism and jeopardize all these gains by writing about this topic?” It’s a rhetorical question. Schwartz goes on to describe an “unburdening,” in which he directed a suicidal client to “ask the light to take [the burden] to where it belongs and just watch until it’s fully out of your system.” Some critics have likened the process of unburdening to an exorcism, because the wording used to expel some ominous force from the body is similar to that of the ancient religious ritual. In Benson’s perspective, this teaches people to believe that “any selfishly destructive or violent thoughts you discover inside yourself, [and] that you can’t find a good reason for having, should be understood as not you, and expunged.”

Which raises the question: What would an unburdening look like for someone who has a serious mental illness that runs in their family? Are burdens genetically inherited, or do they dissipate once and for all after an unburdening session? Schwartz doesn’t seem to have a real proposition for serious illnesses like these. His writings suggest that he thinks medication can have a place in helping the mind’s “firefighters” to calm down, but he cautions readers not to expect to accomplish too much “inner work” while taking it. To many mental health professionals, this language would be a red flag.

IFS has undeniably helped some people manage their mental health issues, but for a treatment that its practitioners sometimes call “a non-pathologizing, non-hierarchical way of working with the varied, difficult, and often contradictory thoughts and emotions we all have,” it seems to have skated far past that threshold. Despite the title of Schwartz’s seminal book, IFS sees particular emotions and “parts” as bad or abnormal—things that need to be fixed. When a theory claims that every question to a societal ill conveniently leads back to one answer, it might be because its proponents willfully ignore the reality: that effective care for mental illness can be just as fragmented as the mind itself.

Hold the powerful to account by supporting The Nation

The chaos and cruelty of the Trump administration reaches new lows each week.

Trump’s catastrophic “Liberation Day” has wreaked havoc on the world economy and set up yet another constitutional crisis at home. Plainclothes officers continue to abduct university students off the streets. So-called “enemy aliens” are flown abroad to a mega prison against the orders of the courts. And Signalgate promises to be the first of many incompetence scandals that expose the brutal violence at the core of the American empire.

At a time when elite universities, powerful law firms, and influential media outlets are capitulating to Trump’s intimidation, The Nation is more determined than ever before to hold the powerful to account.

In just the last month, we’ve published reporting on how Trump outsources his mass deportation agenda to other countries, exposed the administration’s appeal to obscure laws to carry out its repressive agenda, and amplified the voices of brave student activists targeted by universities.

We also continue to tell the stories of those who fight back against Trump and Musk, whether on the streets in growing protest movements, in town halls across the country, or in critical state elections—like Wisconsin’s recent state Supreme Court race—that provide a model for resisting Trumpism and prove that Musk can’t buy our democracy.

This is the journalism that matters in 2025. But we can’t do this without you. As a reader-supported publication, we rely on the support of generous donors. Please, help make our essential independent journalism possible with a donation today.

In solidarity,

The Editors

The Nation