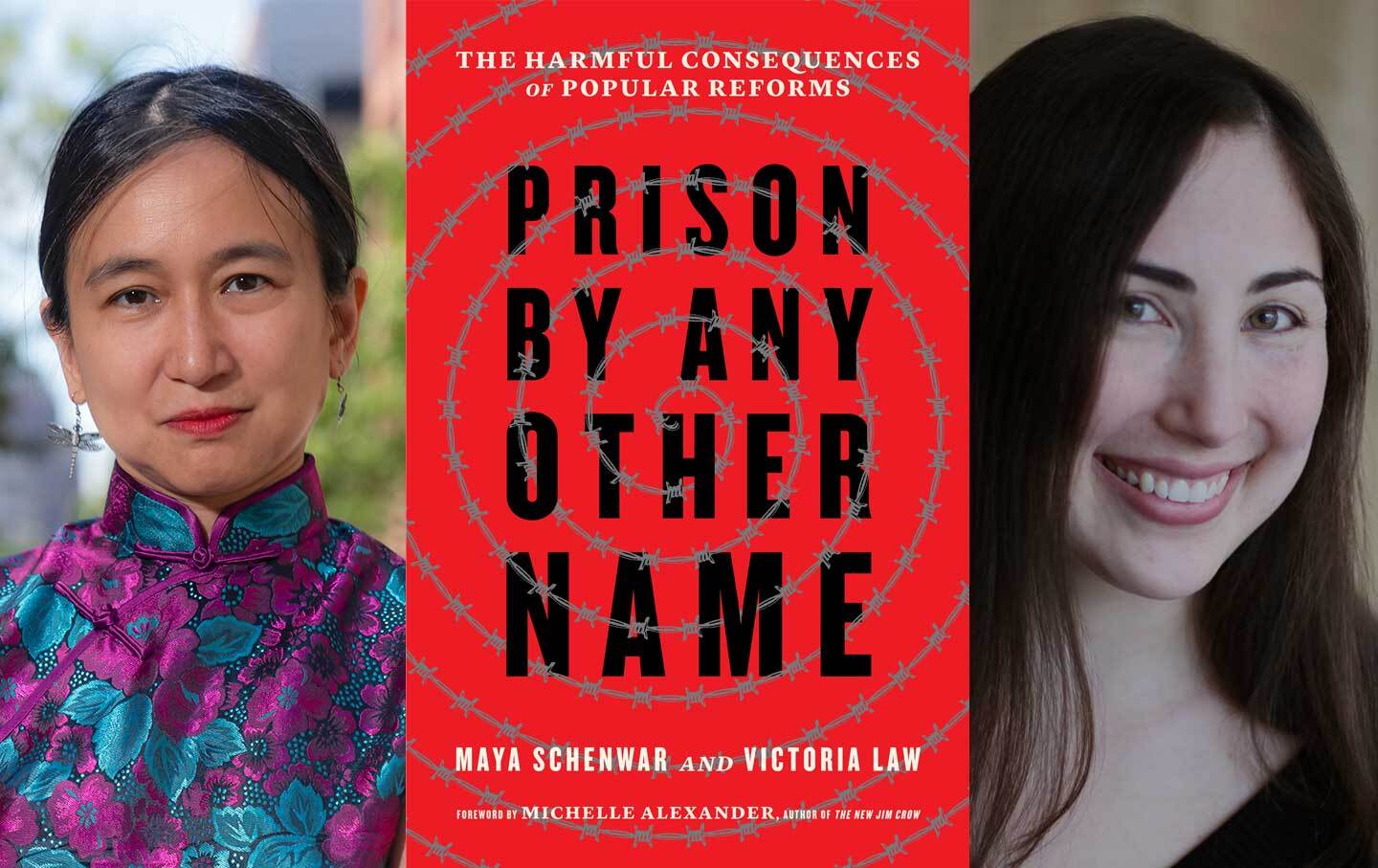

Victoria Law, left, and Maya Schenwar, right, are the authors of Prison by Any Other Name.(Photos courtesy of Victoria Law and Maya Schenwar)

The cry to end mass incarceration has become something of a bipartisan catchphrase in the last decade. Conservative stalwarts like Newt Gingrich and Grover Norquist have decried the criminal justice system’s excesses in such unlikely forums as Ava Duvernay’s documentary 13th, and the Koch brothers have partnered with the Center for American Progress to create the Coalition for Public Safety, the largest bipartisan criminal justice reform organization in the United States. At a glance, criminal justice reform seems like one of the few areas in which people from across the political spectrum can find agreement, even if the total prison population has only seen modest declines since its peak in 2009.

But mass incarceration is not the only way in which people’s lives are upended by the justice system. About 4.5 million people are on some form of community supervision, which increasingly includes restrictive electronic monitoring that can prevent people from being able to buy groceries or attend their children’s sports events. The proliferation of data-driven policing and gang databases have also placed entire communities under the eye of the state with little in the way of due process.

These alternatives to prison often fuel incarceration, the exact outcome they are supposed to prevent. In 2016, at least 168,000 people were imprisoned not for new crimes but because they had violated an element of their parole or probation agreement. As Victoria Law and Maya Schenwar explain in their new book Prison by Any Other Name, reducing our reliance on incarceration will not inexorably lead to a less punitive, restrictive, or retributive justice system. “Working for real freedom,” they argue, “means resisting not only incarceration but all of its interconnected manifestations.” In their book, Law and Schenwar challenge the assumption that there must be a place society sends, isolates, and ultimately disposes of its undesirables, and they make a case for not only abolishing prisons but also building a world in which no person is faced with the threat of state punishment, surveillance, or control.

—Daniel Fernandez

Daniel Fernandez: You both have been writing about prisons and the legal system for a long time. How did you decide that now was the time to collaborate on a book?

Victoria Law: Maya is the editor of TruthOut, and I’ve been writing for the site about issues of incarceration since 2011. We both noticed an alarming trend: People were talking about criminal justice reform and decreasing the number of people in jails and prisons, but what was being proposed as alternatives to incarceration in buildings looked alarmingly like incarceration, except that it expanded into peoples’ homes and communities.

DF: In your book, you discuss how many of today’s “reforms” are not actually making things better for anyone. They’re not enhancing public safety. They’re not creating accountability. They’re not providing opportunities for rehabilitation or healing. How should we distinguish between reforms that actually chip away at the prison state and those that are repackaging punishment and surveillance in new ways?

Maya Schenwar: Something we really try to emphasize in our book is that we should be suspicious of reforms that operate through a logic of replacement. For example, with electronic monitoring, we’re saying, “OK, we still want to criminalize and arrest people, and we’re still going to assign people to the same courts and sentence them, except it’s going to be electronic monitoring as opposed to a prison sentence.” And what we see with these replacement systems is that they do a lot of the same things as prisons. They overwhelmingly target Black people, Indigenous people, other people of color, low-income people, trans people, queer people, drug users. They’re still confining people in physical spaces. They’re still surveilling people and controlling people. They’re still operating by all these same principles; they’re just not actual buildings called prisons.

And it’s not just people who otherwise would have been in prison who are being shackled with electronic monitoring. It’s also people who might have otherwise just gotten probation or not been under the state’s control at all. Maybe they would have had their charges dropped. But since there’s this handy alternative, which still allows them to be under physical control of the state, that’s the route that’s taken.

DF: One of my takeaways from reading your book was how doing nothing—or doing less—when it comes to law enforcement can sometimes be the best course of action. I also came away with the sense that much of what passes for innovation in criminal justice circles is not very novel. What did you take away from those findings, and how did they influence the way you see today’s reforms?

VL: I think it’s helpful to think about a question Angela Davis posed recently: “Does it make sense to reform an institution that began as a reform?” Prisons were a response to capital punishment, flogging, and other violent punishment for acts that were construed as crime. Taking away a person’s liberty and sticking them in an overcrowded prison cell or in a solitary confinement cell was seen as a reform. So if we keep that in mind, we can think of reform as tinkering around the edges of an institution that is punitive at heart, and doesn’t necessarily address why people did what they did.

DF: There have been many conversations around abolition lately, and a wide-ranging discussion on what that term means. Do you feel like there’s support for the changes that you’re advocating in your book? Where do you see the movement going in the next couple of years?

MS: We’re in a really, really exciting moment, and one that has happened very quickly, even though it’s building on a foundation that’s been growing for decades, thanks to the work of Black organizers, particularly Black women, who have been paving the way for this abolitionist moment for a long time. When you mentioned earlier the idea of the state doing less, we are advocating in our book for the state to do less in terms of their surveillance, control, punishment, and policing. We’re asking for a massive relinquishing of control. But we’re not saying the state has no responsibilities. We’re actually asking: “Where should our resources be going? What are things that cultivate not only safety but also well-being? What are things that allow people and communities to thrive?”

The conversations that we’re seeing now around what real health care looks like is part of the abolition. Asking, “How do we address systemic inequalities and injustices that are baked into our educational system?” is abolition. Environmental justice is abolition. Doing work around overtime pay for farm workers is abolition. All of these things are abolition, and that’s coming into the conversation right now because people are saying, “If not the police, then what?” And as Ruth Wilson Gilmore says, the answer is “everything.” We need to be thinking about building a radically different society. I think the energy around that right now is not going to go away. It’s something that opens the door to a vision of a different society.

DF: Something some people struggle with when it comes to thinking about transformative justice frameworks is the possibility that someone who has been harmed might desire a punitive or retributive response. How do you reply to those who want to see that impulse acted upon?

VL: One of the pitfalls of relying on prisons and punishment as our main forms of dealing with harm and violence is that it shrinks the imagination. People think that there are just two choices on the table: You rely on policing and prisons or you do nothing. And that is not the case.

Police and prisons come in after harm has been done, and they don’t necessarily address harm, either. There are plenty of statistics on the numbers of rapes that are reported to police departments, and only a tiny fraction are actually investigated, let alone referred to prosecution (and prosecutors only prosecute a fraction of those cases). It’s like an inverse pyramid: The amount of harm that happens, particularly in Black communities and other communities of color, is often under-reported to the police. Police often don’t take them seriously. They don’t actually investigate or close cases. So police and prisons don’t necessarily even keep people safe or provide the retribution or vengeance that we think victims want.

I also want to be clear: Abolition does not mean there aren’t consequences. But you can have a consequence that is not ripping somebody away from their family and community for years on end, sticking them in a cage, and subjecting them to brutality.

DF: There seems to be a feeling among certain commentators that abolishing the police or abolishing prisons is tantamount to abandoning communities and dismissing the need for public safety entirely. How do you push back against that impulse?

MS: I think that when we talk about taking away the police [in that scenario], it erases the ways in which communities have already been abandoned. The most policed communities are low-income Black and Indigenous communities, low-income communities of color, where all of these resources that are basic for survival are scarce.

Get unlimited access: $9.50 for six months.

When we think about abolition, we’re thinking about abundance, not scarcity. We are thinking about what can foster the survival of people and communities, what can actually make people live and thrive together. And the police are not included, because police are violent. They are part of the problem, they’re actually working against health, working against well-being, working against safety.

Sometimes the conversations around taking away police as being like abandonment are really about how we create collective safety. Like what are the measures that we can take that will actually address violence? Because the police aren’t doing that. And that’s something that we talk about in the final chapters of the book. We look at all kinds of community projects around the country that are taking on these questions: How do you deal with violence? How do you build safety? Ejeris Dixon, someone we interviewed for our book, says that safety is a practice. It’s not just a thing that is given to us. It’s something that we all have to work on.

DF: In the closing section of the book, you return to a quote from Ruth Wilson Gilmore about how abolition is not aspirational but an adventure. What does that mean to you?

MS: I think what Ruthie is saying is that people are already doing abolition. Sometimes, abolition is spoken of as a dream. The people who dismiss it say, “You know, that would be great.” Like, hopefully, in the future, we’ll have a society in which we can abolish prison and police. But we can only imagine it. And what Gilmore was saying, and what a lot of people we interviewed for the book affirmed, is that people are already doing abolition in all kinds of different ways. They’re practicing new forms of building safety or old forms of building safety that don’t involve the police, they’re being creative and working on different projects for how to make their communities work for them.

We’ve seen amazing abolitionist work happening over the past few months in terms of people’s responses to Covid-19 and mutual aid networks cropping up in all kinds of communities. People are getting to know their neighbors and are working together, building community in ways that are completely separate from police and prisons.

Daniel FernandezDaniel Fernandez is an editorial intern at The Nation.