Math and Poetry

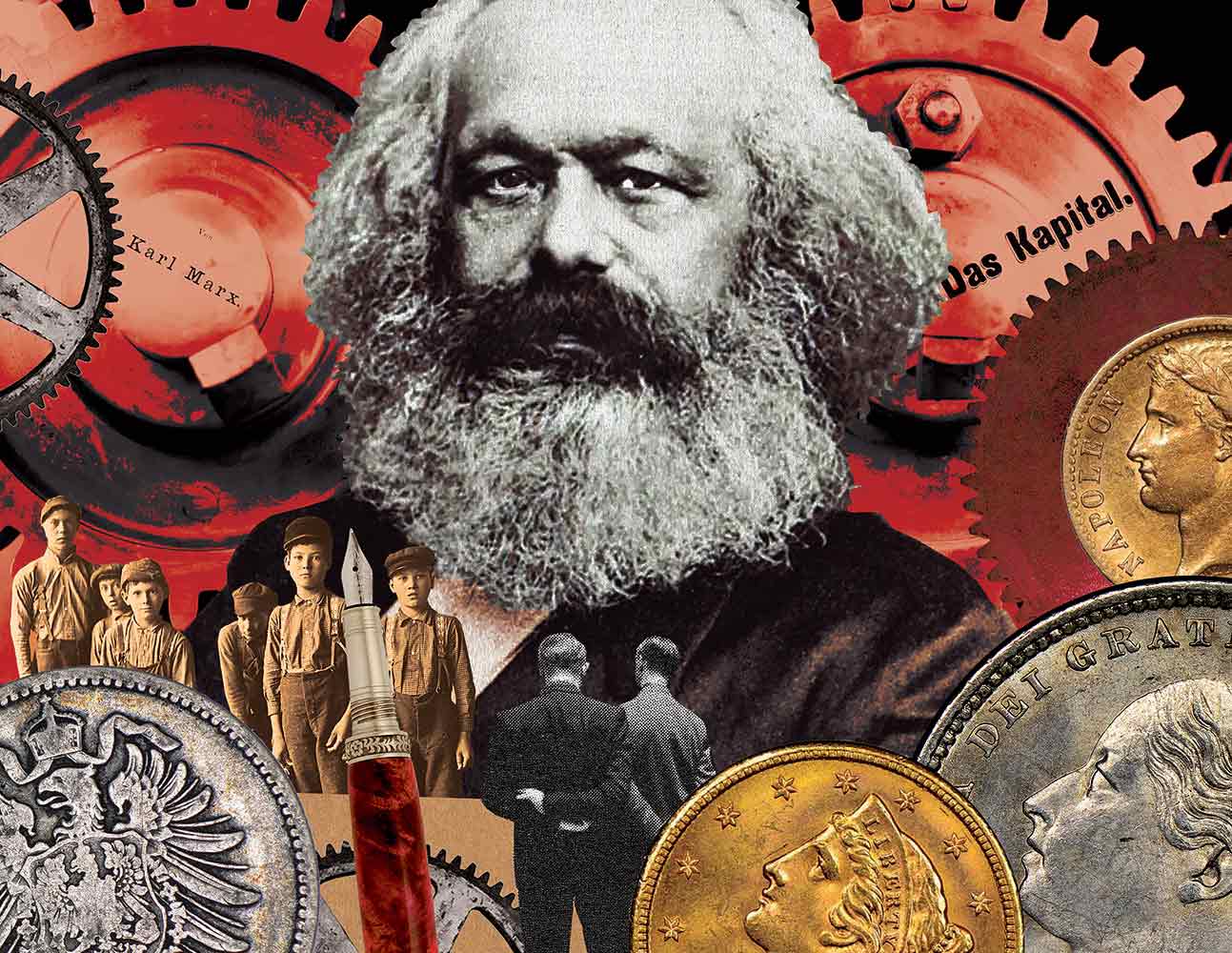

The making and remaking of Capital.

The Making and Remaking of Karl Marx’s “Capital”

In the first English translation in half a century, Paul Reitter and Paul North distill the essence of the Marxist masterpiece by going back to basics.

At any given moment, you can probably find an aging crank holed up in the local public library, complaining of aches and pains, feverishly working on a book they claim will change the world. Most of their efforts will never see the light of day. But sometimes the crank is Karl Marx, and the book being written is Capital.

Books in review

Capital: Critique of Political Economy, Volume 1

Buy this bookUpon beginning work on his magnum opus in the Reading Room of the British Museum in 1851, Marx wrote to his longtime friend and frequent collaborator, Friedrich Engels, that he would be “finished with the whole of the economic shit in five weeks.” As it happened, however, it would be a good 16 years before Volume I—the only part of Capital that would appear during Marx’s lifetime—was finally published, and even then it had to be pried from his reluctant hands. As he wrote to Engels in 1865, “I cannot bring myself to send anything off until I have the whole thing in front of me. WHATEVER SHORTCOMINGS THEY MIGHT HAVE, the advantage of my writings is that they are an artistic whole.” His frustrated wife, Jenny, meanwhile, observed to Engels that this “wretched book…weighs like a nightmare on us all.” Marx would keep rewriting the other volumes until his death in 1883.

Wretched though the process may have been, what Marx ultimately produced was a masterpiece: philosophically rich and empirically detailed, exacting in its analysis of the abstract logic of capital as a relation but rooted in its historical moment, at times discursive and at others pithily cutting. As dense and sometimes forbidding as Capital can be, it has spoken to many audiences. For socialist organizers and labor activists, it offers an eminently recognizable account of overwork and exploitation; for political economists, a meticulous explanation of how commodities come to have value within capitalism’s social order; for historians, a portrait of working-class life in 19th-century England; for philosophers, a critique of modern forms of domination. Other texts by Marx are more polemical or accessible, more overtly condemnatory of capitalism or more immediately gripping—yet none can serve as a substitute for Capital’s investigation, at once rigorous and comprehensive, of the system that has made the modern world.

Capital, Volume I is undoubtedly one of the most widely read political works of modern times—and usually, as befitting a work associated with socialist internationalism, it is read in translation. In 1872, it was translated into Russian, and in 1875 into French, the latter with Marx’s extensive involvement. Since then, it has been translated into 72 languages, often multiple times. Yet in the more than 150 years since its original publication in German as Das Kapital, there have been only three major English translations. The first, by Samuel Moore and Edward Aveling under Engels’s supervision, was published in 1887. Moore and Aveling worked from the third revised German edition, which Engels had edited to reflect the changes he thought Marx had intended to make. This translation remained the standard until 1976, when the social historian Ben Fowkes translated Volume I, working from the fourth German edition (also edited by Engels), restoring sentences that Engels had excised while updating others to reflect changes in English usage. Volumes II and III were also translated by David Fernbach (following previous translations by Ernest Untermann) and published in 1976 and 1981, respectively.

Now, nearly a half-century later, comes a new translation of Capital, Volume I by the Germanist scholar Paul Reitter, coedited by him and the critical theorist Paul North. While appraisals of Marx often begin with some version of the question “Why read Marx today?,” this new edition poses a more unusual question: Why translate Volume I anew?

Reitter and North offer a simple answer: They want to bring us closer to the work that Marx actually chose to publish. Their translation is therefore based on the second German edition of Volume I—the last one revised by Marx himself, and hence the last one he can be said to have authorized. But the new translation does more than simply return us to Marx’s original text. To understand better what he might have meant, it incorporates insights gleaned from new currents of scholarship on Marx that have developed in the many decades since.

What, then, is the Capital of the 21st century? If Moore and Aveling’s translation offered a Marx for the age of the Second International—when working-class militance was on the rise and capitalism’s end seemed imminent—and if Fowkes offered a more literary, discursive Marx for the New Left, then Reitter and North offer us a version of Volume I that is at once more scholarly, laden with editorial notes, and more immediate, stripped down to the textual essentials. It’s a Capital for an unusual age: one in which Marx’s genius is perhaps more widely acknowledged than ever, precisely as the political horizons of Marxist projects have diminished.

Given its immense influence, it’s surprising that there have been so few English translations of Marx’s crowning achievement. By comparison, three new translations of Ludwig Wittgenstein’s Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus—a work of considerable philosophical importance, but certainly not more world-historical significance—have been published since 2023, and another is forthcoming this year. Yet the task of translating Capital, Volume I is particularly formidable. There is, for one thing, its sheer length: The Fowkes translation weighs in at over 1,000 pages. It is also an immensely complex work, one that demands familiarity with technical concepts in multiple fields, most notably political economy and philosophy, and an inescapably literary one, whose arguments are made through striking imagery and language.

Capital is many things at once: It reads like an economics textbook in places, a work of history in others, and a satire still elsewhere; it contains math and poetry in equal measure. Marx painstakingly walks the reader through calculations of the rate of surplus value on one page and then ruthlessly decimates his intellectual enemies on the next. The historian Michael Denning has perceptively compared Capital to another sprawling volume, Moby-Dick, by Marx’s contemporary Herman Melville. Both refuse to adhere to conventional forms, instead leaping from one genre to another. Capital’s unfolding investigation of value is peppered with long asides on Scottish serfdom and ancient Greek philosophy, while the story of the Pequod’s search for the great white whale is interrupted by intricate chapters on cetology and gory descriptions of the process of stripping blubber from a whale carcass. Capital is also a tour de force of coolly reasoned argument, occasionally supplemented by witheringly sarcastic asides. Marx is angry, as North’s introduction emphasizes—and yet for much of the book, he holds his contempt for capitalism and its apologists in check, if just barely. His goal is not to launch a revolution or even to offer a devastating critique—at least, not by way of Capital alone. Rather, he wants to understand in exquisite detail capitalism’s inner workings.

A translator, then, needs the agility to convey the precision of Marx’s technical analysis, the sly wit of his jibes at antagonists, and his evocative but unsentimental portraits of factory life. As Engels wrote in an 1885 essay ominously titled “How Not to Translate Marx”: “To render him adequately, a man must be a master, not only of German, but of English too.”

Perhaps most daunting of all to the would-be translator, as the title of Engels’s essay hints, are Marxists themselves. Any translator of Marx has a guaranteed audience of scholars, both professional and amateur, who have devoted years to understanding the text, who know it inside and out, who are deeply cathected to its famous phrases and images, and who aren’t shy about voicing their disagreements. Marxists are notorious for appealing to what Marx “really meant,” engaging in interminable arguments over the significance of a given passage or the interpretation of an ambiguous clause, often basing considerable political claims on their esoteric readings. To non-Marxists —and many Marxists as well—this scriptural fidelity can seem suspiciously theological in its urge to locate truth in a sacred text rather than through the use of one’s own powers of reason.

Refreshingly, Reitter and North embrace the gravity of this task with both energy and open-minded modesty. Marx’s work on Capital, they note, was “like a river that flows for twenty years,” and they have no intention of attempting to cut off any of its tributaries. Marx, as they recognize, was prone to endless rewriting. He returned to the same questions over and over again; he compulsively revised his work upon absorbing new information; and he often refrained from publishing it for years, even decades, as he sought to strengthen its conclusions.

Marx also faced more practical difficulties. He chronically underestimated how long his projects would take; he tried to do too much at once; and he was constantly broke. As a result, he left an enormous number of his projects unfinished.

Reitter and North have no interest in smoothing the wrinkles and kinks out of Capital. They don’t claim to offer a truly definitive edition, one that could settle the many intra-Marxist disputes once and for all. To the contrary, they recognize that there can be no such thing. Their aim is more modest: to capture, as closely as possible, the text that Marx himself sought to bring into the world.

In this endeavor, Reitter and North join a long tradition of people who have tried to sort through the mass of notes, drafts, partially finished manuscripts, and revisions that Marx left behind. The first, of course, was none other than Engels, who edited the manuscripts of Volumes II and III of Capital, as well as many of Marx’s other texts, and stewarded the first English translation of Volume I. This turned out to be a thankless job; today, Engels is often castigated by a contingent of Marxists who think he botched it. Many scholars now attribute Marx’s supposed “economic determinism” to Engels’s revisions, which were subsequently adopted as authoritative by the Second International.

But the task of bringing Marx’s unpublished work into the world was too vast for Engels alone to finish. When he died, he had yet to complete his edits on an unfinished Volume IV—in reality a collection of earlier notes that Marx hadn’t developed as a volume in its own right. It would eventually be published by Karl Kautsky as a separate text, Theories of Surplus Value.

With the Bolshevik Revolution, the project of cataloging Marx’s work took on new significance. In 1921, David Riazanov, a Soviet revolutionary, historian, and archivist, founded the Marx-Engels Institute in Moscow and set about compiling and publishing the complete collected works of both men—including drafts, outlines, letters, and other ephemera, comprising some 55,000 works in all—as part of the so-called Marx-Engels Gesamtausgabe, or MEGA for short.

When Joseph Stalin came to power, Riazanov found himself on the wrong side of the Soviet leader: He was purged in 1931 and executed in 1938. But the Marx-Engels Institute carried on, becoming the Marx-Engels-Lenin Institute and, later still, the Marx-Engels-Lenin-Stalin Institute, which for decades oversaw the publication of a series known as the Marx-Engels Collected Works. Consisting of 50 volumes, the series was translated into English in the 1960s. (You can buy a complete English set for about $1,500.)

If the Marx-Engels Collected Works stood for many years as the most comprehensive print edition of Marx’s oeuvre, however, the gold standard continued to be MEGA, which as yet is available only in German. Revived as a project in 1975, abandoned with the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, and resumed (technically as MEGA²) in 1990 under the auspices of the International Marx-Engels Foundation, it is today a project of international research not unlike the Large Hadron Collider. Housed in Amsterdam and funded by the European Union with support from a network of institutions, it is worked on by a team of scholars from Germany, Russia, France, Austria, the Netherlands, the United States, and Japan, and is consulted by scholars from just about everywhere.

MEGA² purports to stand apart from the ideological and political pressures that have colored previous editions of Marx. It seeks to present his work in full and as accurately as possible; it is projected to span a staggering 114 volumes upon completion. (So far, we are up to 62.) An entire section of MEGA² is made up of Capital and its preparatory notes, alone comprising an astonishing 15 volumes. It is, in other words, an emphatically scholastic and philological project that positions Marx as one of the great thinkers of modernity. It is the very embodiment of Marxology—a term coined by Riazanov to describe his scholarly enterprise but now usually deployed with some mix of admiration and irritation to describe work that appears inordinately fixated on Marx himself.

Whereas MEGA² marks an effort to make Marx’s work available for reading in full—at least to German readers—other major branches of Marxology have developed new approaches to interpreting it. In the decades since the last English translation of Capital appeared, a new way of understanding the book—and thus Marx—has gained currency, and Reitter and North’s choices are clearly attuned to its preoccupations.

Capital was, for much of the 20th century, understood primarily as a work of Marxist economics centered on the labor theory of value—one strongly associated with Soviet orthodoxy and widely thought to have been discredited by the advent of neoclassical methods. Many New Left thinkers in the 1960s and ’70s moved away from the ostensibly economistic Capital in favor of other, more “humanist” works by Marx, such as the Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts. But Capital wasn’t abandoned entirely: In Germany in the 1960s, students loosely affiliated with the Frankfurt School of critical theory, disillusioned with the Soviet Union but not with Marx himself, began to argue that Capital had been misunderstood. Known as the Neue Marx-Lektüre—the “new Marx reading”—this tendency sought to break with the orthodox readings of Marx and foreground the political elements in his analysis of capitalism. It asserted that Marx was not an economist proposing a new form of economics, but rather a philosopher offering a critique of the political economy of his time. He was not a crudely economistic, deterministic thinker, but one keenly attuned to the subtle yet pervasive transformations that capitalism had wrought in social life.

This reading of Capital has grown in popularity over the decades, persisting even as Marxism fell deeply out of fashion in the academy following the collapse of the Soviet Union. When the 2008 financial crisis and the subsequent political fallout led to a renewal of interest in Marx, the German new reading was the most sophisticated analysis on offer—and one well positioned to speak to a generation hoping to revive Marxism without its Soviet baggage.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →Many of the most au courant Marxist thinkers of recent years have come out of this tradition. The bookish and unassuming German scholar Michael Heinrich, for instance, has become an online celebrity among a subset of Marxists for whom his An Introduction to the Three Volumes of Karl Marx’s “Capital,” rooted in the tradition of value-form analysis that developed from the German new reading, has arguably supplanted David Harvey’s series of companion texts as the essential reading guide. Another touchstone is Moishe Postone’s 1991 Time, Labor, and Social Domination, the most comprehensive theoretical framework to emerge from the new reading tradition and a longtime cult classic that has become increasingly popular. In it, Postone launches a challenge to what he derides as “traditional Marxism” and its understanding of capitalism: The key question isn’t simply who owns the means of production, he argues, but how the means of production themselves have been made by capital—and for that matter, how capital has remade the entire world, down to the most basic experience of time and space. These capacious analyses of Marx have, in turn, informed influential political analyses by the likes of the Endnotes collective and work by prominent figures like the literary theorist Sianne Ngai and the philosopher Martin Hägglund.

If the new reading has been the theoretical juggernaut of the past few decades, other approaches to Marx have also flourished in the past several years, many of them drawing on the unrivaled archival bounty of MEGA². The political theorist William Clare Roberts, in his 2017 book Marx’s Inferno, argues that Capital is not only an “economic” text but “one of the great works of political theory,” one in deep conversation with the socialist republicanism of mid-19th-century England; the political theorist Bruno Leipold’s new book Citizen Marx emphasizes still further the influence of European republican traditions on Marx’s thought and political vision. Another strand of analysis has sought to recover Marx’s ecological thought: The Japanese eco-Marxist Kohei Saito—himself a MEGA² editor—has drawn on the notes Marx took in the last decade of his life to argue that he was not a productivist modernist, as he has often been understood, but rather a “degrowth communist” prescient about contemporary ecological crises.

Reitter and North’s edition of Capital doesn’t take a single position in these interpretive debates, but it is in conversation with many of these new readings and new approaches to Marx—often explicitly so. It is also, in a more fundamental sense, motivated by them: For Reitter and North, new interpretations of Marx are best understood when read alongside a new version of Capital itself.

Both Reitter and North specialize in German studies. Neither is a specialist in Marx, as both freely acknowledge, and so they have recruited an editorial collective to help them navigate the dense thickets of Marxology. This collective includes Michael Heinrich and Kohei Saito along with the Marxist feminist Tithi Bhattacharya, the left-wing (but non-Marxist) economist Suresh Naidu, the German specialist Rebecca Comay, and the data scientist Jeff Jacobs. Although they’ve done their homework within dedicated Marx scholarship, Reitter and North are clearly keen for their Capital to reach beyond the sometimes hermetic world of Marxology, and have tapped a pair of political theorists to offer commentaries bookending the text: Wendy Brown writes the foreword, and William Clare Roberts provides a scholarly afterword.

Each of these supplementary texts addresses different aspects of the work—yet each in its own right reflects the shift in the reception of Marx since 1976. Capital here is positioned not as a guide to economics but as a work of philosophy and critique seeking to parse the multiple levels on which capitalism operates. The project of Capital, as this edition sees it, is to help us make sense of the complexity of a system that is not as it appears. In other social systems, oppression is directly enacted and therefore obvious: When a feudal lord forces his serfs to give up a certain quantity of grain, for instance, or a pharaoh forces his subjects to perform a certain amount of labor, the structure of power is clear. In capitalist societies, on the other hand, the gaps between rich and poor may be just as stark, but the mechanisms of exploitation and the methods of domination are far murkier. Everyone appears to be acting of their own free will: Wage workers enter into contracts of their choosing, and the overall social order seems to emerge from a mass of individual choices. Countless workplaces operate independently, under the private direction of whoever owns them—and yet they are all connected to one another through the globe-spanning networks of trade and commerce that send prices shooting up or crashing down. To understand this system, one cannot simply take it at face value, as economists typically do. One must instead examine its hidden depths, the relationships and forms of power that constitute its inner workings. This, Reitter and North’s edition insists, is the crucial point of Capital: Both essence and appearance, both the material world and its abstract representation, are critical to understanding capitalism.

This overarching perspective on the text comes through most clearly in Brown’s foreword and the editor’s introduction by North. But it is also apparent in Reitter’s approach to translation more generally, as articulated in his instructive translator’s note. In the translator’s introduction to his own edition of Capital, Fowkes had explained his purpose in simple terms: He wanted to reflect changes in the English language and to restore complicated passages that Engels had excised or simplified for readerly ease. Fowkes had also set out to capture the literary quality of Marx’s prose, and in doing so he produced some of the best-known English-language phrases in Marx’s oeuvre. But for that reason, his version of Capital often sounds like the 19th century, or at least how we expect the 19th century to sound: ornately eloquent, grand, even florid. The Fowkes translation can, however inadvertently, lend credence to the idea that Capital is a relic of a past era, better read as a historical document than a guide to present-day politics.

Reitter, by contrast, is notably more self-conscious about the project of translation and more overt in his aim to offer a Capital that is at once more philologically accurate and more contemporary—a translation that can restore the singularity of Marx’s original text while also refreshing it for the present. As Reitter explains, his translation is both more precise and more casual than previous editions: It reflects the specificity and occasional oddity of Marx’s language without weighing it down with rhetorical flourishes. In keeping with the edition’s overall thrust, he is especially attentive to the passages in which Marx seeks to capture the strange association between the world that we see and the underlying relationships that structure it.

Engels’s advice to would-be translators of Marx included the injunction to respect his precise use of language: “New-coined German terms,” Engels insisted, “require the coining of corresponding new terms in English.” Reitter has clearly taken this directive to heart: He strives for technical accuracy, and his Marx often comes across more like an academic, with a penchant for coining his own cumbersome neologisms to describe the workings of the “value-form” as precisely as possible. Such neologisms, Reitter insists, aren’t just accidentally cumbersome; rather, they reflect Marx’s attempt to describe genuinely novel phenomena, things that theorists hadn’t yet found a way to name.

Reitter’s choices are especially important in the first few chapters, which for theorists following the new reading of Marx are the most vital. These are notoriously some of the most difficult passages of Capital: Readers are plunged immediately into a dense dissection of the commodity and its mysteries. In the preface to the first German edition, Marx himself described the opening chapter on the commodity as the “hardest to understand.” In his preface to the French translation, he worried that the “arduous” task of working through the initial chapters would prove “dishearten[ing]” to French readers if the volume had been published in serial form.

But it is in these early chapters that the particularity of Marx’s language is most consequential, and it is here that the significance of this new translation is most apparent. Reitter translates Werthedinge, for example, as “value-things,” Werthkörper as “value-body,” and Werthgegenständlichkeit as “value-objecthood.” These are clunky terms, but this, Reitter convincingly argues, “is part of the point.” (They sound strange in German too, he notes.) These awkward phrases represent Marx’s attempts to capture the oddity of capitalism’s social forms, their uncanny duality. The commodity is two things at once: It is an ordinary object, a physical thing in the world, but it is also a representation of value, with qualities that aren’t immediately apparent, which it is the purpose of Capital to investigate. It is also in these early chapters that the editorial notes are most extensive and valuable, connecting Reitter’s translation choices to the insights of major interpretive developments.

Take, for example, Marx’s discussion of what makes different commodities equivalent: When we set aside the use values of two commodities—say, a T-shirt and a violin—nothing “is left over except the same ghostly objecthood.” The German term is gespenstige Gegenständlichkeit; Fowkes renders it as “phantom-like objectivity.” But “objectivity,” as Reitter points out, seems to mean something more like “reality,” rather than the material sense that Marx means to invoke when describing the oddity of a system in which one physical object expresses the intangible value of another physical object when they’re traded as commodities. More generally, the unusual pairings of language, suggesting both concrete and abstract qualities (“ghostly objecthood”), reflect the broader emphasis on duality in Marx’s analysis of the commodity.

Reitter’s meticulous care with Marx’s terminology, however, doesn’t inhibit his efforts to render other language in the book more colloquial. In lieu of Fowkes’s tendency toward literary turns of phrase, Reitter has embraced a greater simplicity of language—in part to set the genuinely “weird” phrases of Marx’s own invention in starker relief. The resulting text is remarkably crisp and contemporary, laden with contractions and slang, at times even bordering on the conversational. It is both highly readable and occasionally deflating, at least relative to the stylistic grandeur of Fowkes’s choices. Instead of the proletarian who sells their birthright for a biblical “mess of pottage,” here we get the more prosaic “lentil stew”; capital remains vampiric, but merely “drinks” living labor instead of monstrously “sucking” it. The mysterious, almost otherworldly “hidden abode of production” is now just a plain old “hidden place.”

Most of these changes, however rhetorically jarring, are substantively insignificant. But some serve to clarify the meaning of Marx’s arguments. One particularly notable change comes in the discussion, late in Volume I, of what Fowkes rendered as “so-called primitive accumulation,” and which Reitter translates as “so-called original accumulation.” The phrase “primitive accumulation” has long been decried by scholars as misleading, and the update, however minor, reflects an overdue change. It also lends clarity to subsequent debates about Marx’s understanding of capitalism.

The phrase appears in a section in which Marx attempts to refute Adam Smith’s account of the origins of capital itself—of how some people come to command the labor of others. According to Smith and other economists, class division was the result of “previous accumulations” garnered by the capitalist’s sheer effort and frugality. The capitalist had toiled and saved while others lazed about, and now he could rightly make others work in his stead. Marx, however, is scornful of this “vapid children’s fable” and offers his own story of capital’s origins. Those wealthy enough to buy the labor of others, he insists, hadn’t simply worked harder; rather, they had forcefully dispossessed others of the land that had once provided their livelihoods. English landlords had enclosed the common lands used by peasants, converting shared resources into private property; European colonialists had conquered India and the Americas and enslaved Africans—all instances of violent and often murderous expropriation that created a class of property owners able to lord their power over a class of propertyless people left with no choice but to sell their labor. Only after this class relationship has been established, Marx notes, could exploitation operate primarily through capitalism’s “silent force of economic relations,” wherein workers who lack productive property are compelled to obey orders in exchange for a wage. Thus, although capitalism is often said to be a system of noncoercive, consensual exchange, Marx sought to show the brutality built into its foundations.

A reader could get all of this from Fowkes’s translation as well. But the switch from “primitive” to “original” clarifies another dimension of the argument. Marx is often read as saying that “primitive accumulation” was a singular moment located in the ancient past, at the moment of capitalism’s birth. But Marx is clear in Capital that acts of “original accumulation” persisted into the 19th century, as reflected in his references to the clearance of the Scottish Highlands and plans to privatize land in Australia. The shift in terminology also addresses a related ambiguity in Marx’s thought: The term “primitive accumulation” has often been thought to evoke a “stagism” frequently associated with Marxism, in which capitalism represents a step forward from precapitalist (or “primitive”) societies, to be eventually superseded by socialism. The term “primitive accumulation” can seem, as a result, to imply a link between the “primitive” nature of the accumulation and its brutality, or an implicit connection between “primitive” non-European societies and savagery. Yet Marx means nothing of the kind. Violent expropriation was not “primitive” in the sense of “premodern”; it was, instead, the origin of class society and thus a fully modern phenomenon. The violence that Marx is condemning is firmly rooted in European law; and his target here is the theories of classical political economists like Smith.

The passages on “so-called original accumulation” are among the most explicitly condemnatory in Capital—although here, as elsewhere, some of the rhetorical force is lost by the choice of source text. Missing, for example, is a line from a later German edition that Fowkes translates as “the history of expropriation is written in the annals of mankind in letters of blood and fire.”

It’s hard, in such moments, not to feel some nostalgia for Fowkes’s loftier prose—especially particular phrases long inscribed in one’s mind. But the overall result of Reitter’s translation is a Capital that’s alive and enticing. Even minor differences in phrasing are remarkably effective in making the text strange, even new. By stripping out some of the most cherished and familiar language, Reitter forces us to confront the text directly rather than skimming over the parts we think we know. It feels, in places, like reading Capital for the first time. Of course, this function has diminishing returns and will be effective only for those who are already (too) enmeshed in the older translation. Perhaps one day this edition will be the one etched in people’s memories, and the Fowkes will serve as a palate cleanser.

Regardless, this simple act of defamiliarization is a virtue in itself: It serves as a reminder to Anglophone audiences that we are always reading Marx in mediation, that the words on the page weren’t simply handed down from on high. The more translations of Capital we have, the less we can rely on any single version of Marx’s prose, and the more we’ll have to argue for our own interpretations and analyses rather than appealing to the words of the great man.

Reitter’s translation will richly reward those well versed in Marx in addition to those approaching Capital for the first time. But ultimately, does it matter—at least to any but the most devoted Marx heads—that there is a new version of Capital in the first place? Who is this Capital for?

It’s not obvious that Capital would ever have had a particularly wide readership. Relative to Marx’s shorter and more polemical works, it has always been a demanding text. When it was translated into Russian in 1872, the censors permitted its publication on the grounds that although it was “socialist through and through,” it was “not a book accessible to everyone,” concluding that “few people in Russia will read it. Even fewer will understand it.”

And yet, for all its complexity, Capital has long offered a way for those subjected to capitalism’s degradations to begin to understand them. As soon as the original version was published, the German American communist Friedrich Sorge reported, workers in the German General Labor Union of New York were already meeting weekly on the Lower East Side, in a “low, badly ventilated room in the Tenth Ward Hotel,” to read it together. Indeed, Capital was once so widely read that it came to be known as the “Bible of the working class,” as Engels famously described it in the preface to the first English edition in 1886.

In that same preface, Engels also proclaimed that capitalism itself was nearly exhausted. A century later, it persisted; and yet the Belgian economist Ernest Mandel doubted, in his own preface to the 1976 Fowkes translation, that “capitalism will survive another half-century of the crises…which have occurred uninterruptedly since 1914.” A half-century of crises later, capitalism survives—and as long as it does, Capital will remain relevant. As Brown notes in her foreword: “The world we inhabit today is unimaginable without capital but also without Capital.” The former is what makes our world and orders our daily lives; the latter is still our best guide to understanding how it does so.

If this edition of Capital is assured of its analytical relevance, however, it expresses little of the political confidence proclaimed by its predecessors. Gone is the certainty that capitalism will be felled by its own crises or interred by its proletarian gravediggers. Reitter and North pitch their Capital more as a guide for students than for revolutionaries. There is, as a result, something melancholic about this edition. It marks a shift in Marx’s status, a step in his elevation to serious philosopher—but perhaps at the cost of some of his political potency. By reading what Marx actually published, we might get closer to what he really meant, but we seem unlikely to get any closer to the end of capitalism.

Socialists with an activist bent often cite Marx’s famous admonition that “philosophers have only interpreted the world in various ways; the point, however, is to change it.” This isn’t an injunction against interpretation, as it’s sometimes suggested to be: We have to interpret the world in order to change it, as Marx well knew. As Roberts reminds us in his excellent afterword, Marx’s purpose in Capital was to “disclose the facts about the dynamics of a society dominated by the capitalist mode of production.” The details of one translation or another matter only insofar as they help us see those facts more clearly—and Marx knew this, too. Marx approached his translations, Roberts notes, with “laborious unfussiness,” toiling over the French version of Capital while often rewriting the text to render the original German less literally. We should take care, Roberts warns, not to get so attached to any particular phrase or exegesis that we forget that Marx himself was constantly rethinking his own positions in light of political developments.

If Capital’s relevance is a function of capitalism’s persistence, we are likely to be reading it for some time to come—and yet Marx’s corpus, however thoroughly studied, can only ever be a starting point. The project of Capital—to expose capitalism’s workings—is one that Marx couldn’t have completed even if he had finished all the planned volumes. The project of capturing an enormously complex, constantly metamorphizing, historically fluctuating system isn’t only too much for any single person—it’s one that could only ever be incomplete, one that must perpetually be taken up by new generations. To continue the work that Marx started is to adopt his mode of relentless rethinking, revising, learning. So read Capital, in whatever translation you can find (Moore and Aveling’s is available for free online), and perhaps you’ll find that the world looks a little different; perhaps you’ll want to do some thinking, critiquing, and writing of your own. Might I suggest the public library?

More from The Nation

A Civil Rights Veteran Revisits the Summer of 1965 A Civil Rights Veteran Revisits the Summer of 1965

The white college student supported Black voters in segregated Alabama, and began documenting the front lines of the voting rights fight, which locals continue to disregard.

Notes on Transsexual Surgery Notes on Transsexual Surgery

An abundance of plastic surgery is not a net good. But discussions over its morality would be better off viewing it less as unfettered desire and more as self-determination.

I Led the FDNY. Don’t Believe Elon Musk’s Nonsense About It. I Led the FDNY. Don’t Believe Elon Musk’s Nonsense About It.

Musk’s attack on the new FDNY commissioner proves he knows nothing about how modern fire departments work.

What Black Youth Need to Feel Safe What Black Youth Need to Feel Safe

Young people are facing a mental health crisis. This group of Cincinnati teens thinks they know how to solve it.

Trump’s Death Eaters Are Coming for Our Kids Trump’s Death Eaters Are Coming for Our Kids

After taking countless lives around the world, RFK Jr. and his ghoulish compatriots want American children to suffer too.

The Supreme Court Just Held an Anti-Trans Hatefest The Supreme Court Just Held an Anti-Trans Hatefest

The court’s hearing on state bans on trans athletes in women’s sports was not a serious legal exercise. It was bigotry masquerading as law.