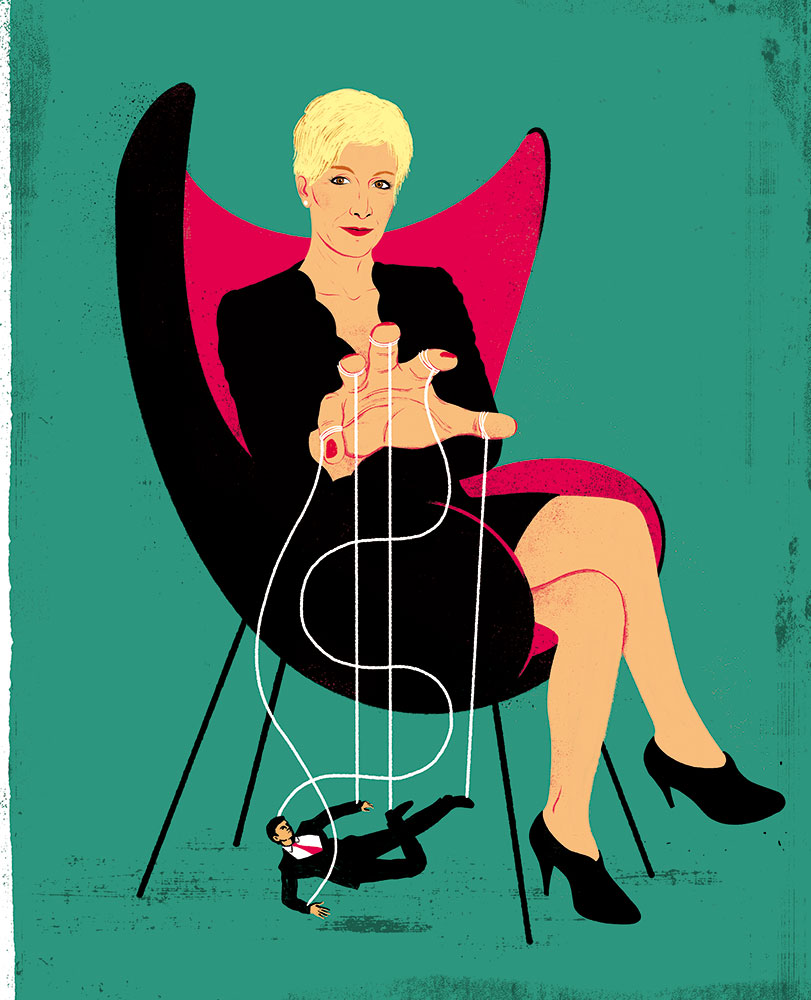

Illustration by Adrià Fruitós.

I picked my life coach because of his picture. He was fit, had kind eyes and a winning smile—an aspirational stand-in for the gay man I wished I was. At 33 years old, I had never been in a relationship, and I wanted to change that. For years, I’d been in psychotherapy—recovering from sexual violence and working through my fear of physical intimacy—but I had hit a wall. I didn’t want more analysis of my avoidant attachment styles or the reasons I take pleasure in withholding. I wanted results. I thought life coaching would be different. I booked a Zoom consultation.

“[Something] I could really help you with is the relationship part. I’m in a nine-year relationship. I had a relationship for five years before that,” the coach, who we’ll call “M,” said. “It’s about meaningful connection. And I actually think you’re going to be really good at it—like, I already know—because of your authenticity.”

“I just don’t think I’m that good at sex,” I said with my bracing authenticity. “I’m not confident in my abilities. I don’t think I’ve had enough experience.”

“Do you feel like you’re overthinking when you’re having sex?”

“Always. I don’t know how to get out of my brain.”

“Being in the present moment is going to be a big part of you getting better at sex.”

This was exactly the sunshine wisdom I was looking for. M seemed like the real thing. He had an enthusiastic demeanor and made eye contact with the camera while talking with his hands. On the other end, I had a broken tooth that I was too cheap to get an implant for and was wearing thick-lensed glasses. We were two gays: one hot, one not. If I wanted what M had, I just had to follow his example by choosing thoughts that served me and continuing to show up. How hard could this be?

I had been introduced to life coaching through “Master Coach Instructor” Brooke Castillo’s Life Coach School, where M had received his certification. I found the school through The Life Coach School Podcast, one of iTunes’ top-rated business podcasts, which I have been listening to, on and off, for the past seven years. It was an unlikely match: I was a Bushwick raver who moshed to industrial techno, getting life advice from a soccer mom in Texas with a predilection for all-white furniture. But her energy was electric, and it made me feel unstoppable. Each week, Castillo spoke what sounded like practical wisdom into my earbuds in a giggly but assertive voice that made me want to trust her. “If you want success, you need to double your rate of failure.” Burnout happens when “your result has become more important than the journey.” “The only thing that changes an emotion is changing the way you think.”

Castillo was unlike anything I had encountered—robotic, spiritual, seductive. Her advice was a cocktail of cognitive behavioral therapy mixed with New Age wisdom and self-help guidebooks. She had an exotic backstory: She was the daughter of an heiress and had once joined a cult (which seems more than coincidental). A promotional video on her website shows her in a magenta dress, sitting regally in front of a pool on one of her grand properties, with a desert landscape behind her. I was ready to do anything this woman told me to do. In the span of one 20-minute episode, I decided I could build 10 pounds of muscle and get shredded, too. I could overcome my fear of rejection and pick up hot strangers in bars.

The episodes had titles like “Creating Confidence,” “The Truth About Burnout,” and “Owning Negative Emotion,” all of which appealed to me. Since 2014, Castillo has offered her podcast as a preview of what it would be like to be taught by Castillo herself at the Life Coach School in Texas. Online, you can enroll in Self Coaching Scholars, an online group coaching program, for $297 a month, or the Coach Certification Program, a three-month online course on how to become a life coach yourself, priced at a whopping $18,000.

And it works—up to a point. The podcast is useful on a day-to-day level, but the more I looked into it, the more I realized that life coaching was not just a booming business but a way of life. The coaching mindset dictates that clients focus on themselves and mobilize the power of positive thinking to overcome their circumstances. A phrase Castillo uses on her podcast is “explosive growth,” and although “explosive” seemed creepy to apply to my sex life, I did want “growth.” But I soon discovered that improving my dating prospects through the coaching model wouldn’t just be about persistence and higher vibrational energy—it would require focusing on building and expanding my personal brand. To succeed, I would need to apply a business strategy to my romantic life. I started wondering if I would be an aspirational purchase, like the newest-generation iPad, or something more mundane, like wired headphones from the gas station. This sort of question was exactly why I had gone out of my way to keep sex and dating separate from the encroaching omnipresence of careerism. Was I willing to make such a change?

On the market: Scrolling through prospective matches on the Tinder dating app.(Erin Clark for The Boston Globe via Getty Images)

The chaos and cruelty of the Trump administration reaches new lows each week.

Trump’s catastrophic “Liberation Day” has wreaked havoc on the world economy and set up yet another constitutional crisis at home. Plainclothes officers continue to abduct university students off the streets. So-called “enemy aliens” are flown abroad to a mega prison against the orders of the courts. And Signalgate promises to be the first of many incompetence scandals that expose the brutal violence at the core of the American empire.

At a time when elite universities, powerful law firms, and influential media outlets are capitulating to Trump’s intimidation, The Nation is more determined than ever before to hold the powerful to account.

In just the last month, we’ve published reporting on how Trump outsources his mass deportation agenda to other countries, exposed the administration’s appeal to obscure laws to carry out its repressive agenda, and amplified the voices of brave student activists targeted by universities.

We also continue to tell the stories of those who fight back against Trump and Musk, whether on the streets in growing protest movements, in town halls across the country, or in critical state elections—like Wisconsin’s recent state Supreme Court race—that provide a model for resisting Trumpism and prove that Musk can’t buy our democracy.

This is the journalism that matters in 2025. But we can’t do this without you. As a reader-supported publication, we rely on the support of generous donors. Please, help make our essential independent journalism possible with a donation today.

In solidarity,

The Editors

The Nation

In 2020, when the pandemic drove people indoors and online, the Life Coach School made $37 million in revenue. “You can create the life of your dreams in a matter of five days,” read one of their advertising slogans. We certainly had the time. Out of thousands of life coaches who studied with Castillo, over 200 graduates of the school’s certification program have gone on to make at least $100,000 a year from life coaching businesses of their own; 27 of them make over $1 million a year, and three make over $10 million, according to the statistics on Castillo’s website.

This is a lucrative trade, and it is only growing. According to the International Coaching Federation’s 2020 report, the number of life coaches grew by a third from 2015 to 2019. In an industry where certification largely goes unregulated, any laughing woman with nude makeup or bearded yogi in a man bun can claim to be a life coach on social media and open up for business. On her website, self-identified “Wealth Coach” Eleena Katz, for example, offers “Money Healing” sessions and populates her Instagram feed with taglines like “Discipline is the courage to become the you who has it all.” In one TikTok video, “Intersectional-feminist dating coach” Date Brazen instructs followers to “Envision what you want,” “Let that vision take up space in your mind,” and “Shake your body.”

Life coaching may be culturally cringe-worthy, but I couldn’t look away. Right from the beginning, Castillo’s approach to self-help as metacognition felt practical: In a video on her website, she says, “The way that I’m a life coach is just someone who helps you witness your own mind, so you can change it to get what you want.”

One task Castillo asks of her clients is to write out their thoughts in a furious and unbroken stream of consciousness. When they reread it, they can observe their own thoughts with the detachment of a scientist and then pick and choose which they want to keep, which to throw away, and which to rewrite in their favor. Borrowing language from guided meditations, Castillo describes the practice of observing her negative emotions and letting them pass through her body as meaningless vibrations. “Good” and “bad” are neutralized into “pleasurable” and “painful” emotions that make up “a biofeedback system indicating what we’re thinking about.” If the emotions that hold us back—anxiety, embarrassment—are just intrusive energy, one can let them fade like a passing rain. “I genuinely am willing to feel any emotion,” Castillo says. “I know that the worst that can happen is an emotion, and I’m genuinely unafraid of feeling it.”

At first, this seemed inoffensive, even helpful as a possible alternative to the pharmaceutical industry’s drug-pushing for depression and anhedonia. But are negative emotions really the worst that can happen? A model in which the wrong thoughts, not circumstances, lead to depressive feelings risks absolving society of any wrongdoing that might have caused our depression to begin with. For all its talk of “change,” life coaching is more of a strategy for adaptation than anything else.

According to this logic, my abysmal dating life wasn’t the result of the hyper-individualization of algorithmically tailored social platforms or the outsourcing of romance to apps that treat dating like shopping. Rather, it was my mindset that was getting in my way. If my dating problems were my fault, that meant I was in control of them. I was not trying to change the world. I was just trying to get laid. And I had the power to make it happen.

Mand I started with practical advice. “Most of my clients can show up, right? They can go on dates, but they can’t keep the boyfriend,” he said. “And then they’re like, ‘There’s no one out there for me.’”

I nodded.

“So we’ll practice by having you put yourself out there. Because it’s not going to be like rainbows and butterflies. I wish life was, but you know the 50-50 concept, right?”

Get unlimited access: $9.50 for six months.

I did. It was a reference to Castillo’s principle that the balance of emotions is a 50-50 split between positive and negative. “Half of your life is going to be, and should be, negative emotion,” she says in a 2016 podcast episode. Often, we’ll resort to things like overeating or alcohol to avoid feeling these painful emotions. But in the spirit of what she calls “minimalism,” eating or drinking or snorting less means sitting with pain—either letting it pass through you as “part of the deal” or changing the very thoughts that cause more pain than necessary.

I could get down with this. But some of Castillo’s other koans are more shallow. “Money makes you more of who you are,” she says in a later episode, adding that “people who always want to produce more, who always want to over-deliver,” get rewarded. As a freelancer, I often work weekends and spend unpaid hours pitching clients, which is understood to be part of the deal. I regularly update my website, send out my CV, and subscribe to paywalled job listings in my field. During my leisure time, I populate my Twitter and Instagram accounts with witty and refreshing content, cultivating my personal and professional brand to remind potential clients that I exist.

M seemed to encourage more of this sort of practice when he told me, “What I’m actually doing with people is helping them brand themselves so they can market themselves, because that’s basically what we’re doing all day long, like all the time, right?”

I had always seen romance as a refuge from work, but M seemed to suggest it was an extension of it. He appeared to recommend that I treat myself like a product, writing strong marketing copy for my dating profile. Should I also list customer reviews from past partners? I was, at best, three and a half stars, or worse: “This product has no reviews.” I’d never had a boyfriend before, so the idea of this made me feel like I was a plywood coffee table on Overstock.com that got discounted because no one wanted to buy it. While it once seemed empowering to think that these problems were in my control, the flip side meant that my failure was distinctly my fault. I needed to think harder, better, faster, stronger.

I pivoted into Sad Boy Mode. “I have this idea that I’m not marketing a product that’s very good,” I confessed. “And so, when you’re trying to sell something that you secretly don’t think is good, it’s not gonna work.”

“You have to believe in whatever you’re selling,” M said.

It was this logic of commodifying the self that disillusioned me. But the reason I had become interested in life coaching to begin with was because I had benefited from something like it in the past: my Alcoholics Anonymous sponsor. In 2020, my sponsor took me on for free, as is customary. The only requirement was admitting that I was an addict. The program is certainly not perfect: Identifying as an addict, even in recovery, sometimes feels stagnant—but, for a time, it was a sanctuary for me.

In AA, as opposed to in life coaching, I would achieve my goal—a total overhaul of the self—within a community of fellow addicts. My sponsor required me to attend three AA meetings a week on Zoom, during which people shared their struggles over the past week. It was more than just me and a paid coach.

Step Two of the Twelve Steps states, “We came to believe that a Power greater than ourselves could restore us to sanity.” Though some participants read this as a religious injunction, many fellow addicts explicitly interpret the “Power greater than ourselves” not as some godly figure but as the community itself. Never before had I participated in such a plural community: ex-convicts, porn stars, cable news anchors, gang members, and Trump-voting burnouts, all sending motivational memes in the WhatsApp group chat, united by our mutual struggle. Once, when one of us was in financial trouble, the group got together and pooled our stimulus checks to help him get through the next month or so. This was not “self-care,” in the words of wellness blogs and motivational TikToks, but a working model of mutual aid.

The crucial difference between AA and life coaching is that in the former, recovery is necessarily communal. Even if one’s pain might be individually felt, the AA solution is to look outward, to connect with others, to share in a mutual understanding of vulnerability, brokenness, failure. Another important difference is that AA is free. While life coaching as a therapeutic model may not be inherently harmful, it reproduces the ideology of the profit motive. It promises to turn clients into, in the words of Max Weber, a “heroic entrepreneur,” conditioning people into thinking of themselves as products, which was a Faustian bargain I realized I wasn’t willing to make.

I was convinced that if I signed up with M as a client, I could easily book three dates a week, get myself into a rhythm, and build confidence to approach guys out of my league. But in the end, I decided not to pursue life coaching. It felt mechanical and certainly wouldn’t ensure happiness. I already knew how to market myself, and there was something gross about approaching my dating life like a business.

I wondered if my problem might even be that I’m too willing to market myself—presenting to the world like a global citizen; an intellectual in designer clothing; a man of taste and charisma and good times in the land where “every problem is an opportunity if you decide it is.” I had already been doing this professionally, and to do this on the dating market would be exhausting and probably demoralizing. I didn’t want to curate six to nine pictures of myself from gallery openings and pool parties to make myself seem more confident on dating apps, or write a bio that said the most exciting thing in life was “trying something new.” I wanted realness and intimacy. Promoting myself as competitive and attractive “on the market” seemed anathema to my conception of love as an understanding of mutual brokenness.

The love that I want to attract isn’t about profit and loss, or doubling my rate of failure to start seeing gains. It’s not a zero-sum game. This kind of love is a gift economy: It gives without expecting a return on investment. Inefficient, interdependent, pointless, patient, kind. I would not “earn” or “deserve” this love by manufacturing scarcity and zeroing in on a target audience. Love might simply come, so long as I opened myself up to it.

One night, I caught myself bitching about my dismal dating life to a friend, who I’ll call S. It was four in the morning, and we ended up at a Mexican restaurant in East Williamsburg—a New York neighborhood that once was considered hip.

I said, “I don’t know how to communicate this idea to someone: ‘Look, I’m damaged goods, busted as hell, and I have too many feelings. I’m still recovering from sexual trauma, and I can’t do this on my own. I need someone to help me, to be patient, and to be OK if things are awkward and uncomfortable before they start getting good. I can’t even promise it’ll be worth it in the end, and in fact, it might not be. But are you willing to take a chance on me?’”

S wiped his lips with a napkin. “Maybe you should just say that,” he said.

“Ha, maybe I should,” I replied.

I’ll let you know how it goes.

Geoffrey MakTwitteris a writer based in New York. He is the author of Mean Boys, an essay collection due out next year from Bloombsury.