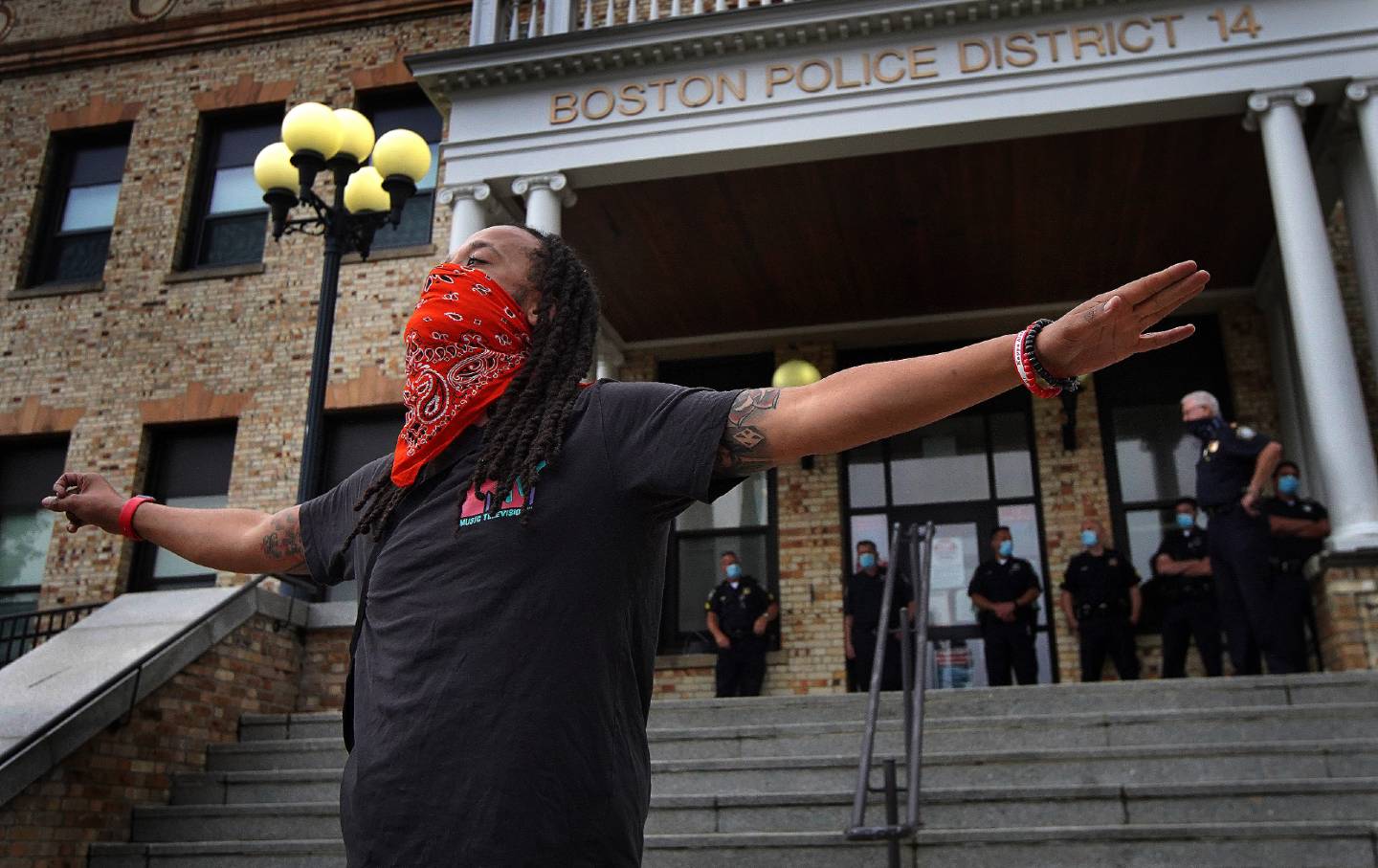

Ernst Jacques speaks to demonstrators during a Solidarity for Black Lives Rally in Boston.(Barry Chin / The Boston Globe via Getty Images)

Covid-19 spread is accelerating across the country. In states as politically divergent as Texas, Oregon, Florida, California, and Arizona, daily case counts are soaring and test positivity rates are up—indicators that portend the grave possibility of an ensuing increase in Covid-19-related deaths.

And yet, some people are still refusing to mask.

At a time when other nations, even those with fewer resources and larger populations, are taking elaborate measures to control the spread of Covid-19, some Americans refuse even the most rudimentary precautions, exposing themselves and others to extraordinary, and unnecessary, risks. This is partly why the United States now boasts the highest number of Covid-19 cases and more than a quarter of global deaths.

But anti-maskers are not just a reflection of governmental or personal apathy toward pandemics. They reveal a deeper antipathy that is worth exploring.

When the president or vice president refuses to wear a mask that protects others, in a pandemic known to disproportionately kill Black and Latinx populations, masks are not only being politicized. They are also being racialized or used to further dangerous racial divisions.

When predominantly white-led crowds of largely unmasked protesters, some armed, take to statehouses to rally against the most basic public health advice—or refuse to mask while shopping—they are not just signaling their political affiliations. They are also performing their racial dominance, manifest, in this case, as selective exemption from the imposition of governmental control.

And while protesters in states like Texas, where case counts have now reached record highs, declare that “Bar Lives Matter,” at a time when others are marching to confront the intersecting forms of violence that shorten Black lives, they evidence more than a difference in priorities. They are illustrating a certain disdain.

This is how racialization works. It assigns risks and rewards to racial or ethnic groups and engages political processes to enshrine those inequalities in laws. In this way, opposition to public health interventions, like masking, have also become a material manifestation of America’s racism, particularly anti-Black racism.

Some of the most insidious and harmful manifestations of anti-Black racism are laws and policies that codify the separation, or segregation, of Black populations outside conceptions of who is deemed “the public.” This dehumanizing practice is often done to place Black people outside the shared benefits of collective, public investments. Thus “the public” becomes coded as white, and public investments empower, privilege, normalize, and favor predominantly white neighborhoods, schools, and workplaces. This undermines the mutuality all public goods depend on for efficacy, and ultimately, places the entire population, not just Black people, at greater risk. Because the root of anti-Blackness is anti-humanism. And efforts to exclude Black folks from the security of public supports also erode the structures on which everyone relies.

For example, anchoring notions of “public safety” in militarized police powers and outsize police budgets doesn’t just contribute to greater violence against populations of color, particularly Black people. It enables violence against all civilians, limits available resources for critical public services like infrastructure and education, and corrodes public trust in vital systems like health care. Similarly, while distorting notions of “public benefits” through racialized and gendered tropes about beneficiaries threatens access to those benefits for certain groups, it also reduces support for universal public programs like Medicaid. This is a historical pattern.

When pandemics strike, state violence and neglect are used to racialize death and disease, shape public conceptions of risk, propagate notions of scarcity, and distribute resources in ways that widen racial inequities. This is what occurred in cities like Chicago during the “Spanish” influenza. And it is what is occurring across the United States right now.

Donald Trump’s cruel and chaotic second term is just getting started. In his first month back in office, Trump and his lackey Elon Musk (or is it the other way around?) have proven that nothing is safe from sacrifice at the altar of unchecked power and riches.

Only robust independent journalism can cut through the noise and offer clear-eyed reporting and analysis based on principle and conscience. That’s what The Nation has done for 160 years and that’s what we’re doing now.

Our independent journalism doesn’t allow injustice to go unnoticed or unchallenged—nor will we abandon hope for a better world. Our writers, editors, and fact-checkers are working relentlessly to keep you informed and empowered when so much of the media fails to do so out of credulity, fear, or fealty.

The Nation has seen unprecedented times before. We draw strength and guidance from our history of principled progressive journalism in times of crisis, and we are committed to continuing this legacy today.

We’re aiming to raise $25,000 during our Spring Fundraising Campaign to ensure that we have the resources to expose the oligarchs and profiteers attempting to loot our republic. Stand for bold independent journalism and donate to support The Nation today.

Onward,

Katrina vanden Heuvel

Editorial Director and Publisher, The Nation

A stark racial divide is emerging surrounding perceptions of Covid risk. And as this pandemic intensifies and the racial gaps in its impact widen, efforts to skirt public precautions like masking seem to closely follow. In April, a Pew research study found that Latinx and Black adults are far more concerned about Covid hospitalization and unwitting spread than white adults.

This racial divergence may arise, in part, from early messaging that attributed risks for Covid-19 to race, underlying illness, and age. Many of these messages have since been clarified. Public health experts have named racism, and not race, as a major risk factor for Covid-19 racial health inequities. They have reported the links between social conditions, environmental racism, and underlying disease that likely render populations, particularly communities of color, at risk for Covid-19 complications. And they have identified the greatest racial gaps in Covid-19 mortality rates not among the elderly, but rather between Black and white Americans aged 34–45.

Yet despite these shifts in understanding, Covid-19 risks and dangers continue to be inaccurately assigned to racial or ethnic groups, leaving the conditions that endanger or place certain racial or ethnic groups at greatest risk unacknowledged, underfunded—and ultimately unaddressed.

These are the enormous consequences of racializing public health.

Because while some may choose not to mask out of inconvenience or ignorance, the harrowing effects remain the same. At this point, some families have lost multiple members; unemployment is the highest since the Great Depression; and restrictions on gatherings prevent many from fully grieving their losses. Yet, month after month, as this pandemic rages on unchecked, unmasked protest continues, undeterred. This includes the president who—unlike the vice president, who has since supported masking—continues to stoke opposition while appealing to the iconography of white supremacy, despite its placing his base, and as a result, everyone in the country, at greater risk of disease and death. Even Twitter sarcastically announced that it will finally allow its users the long-requested ability to edit tweets—but only when “everyone wears a mask.”

And this is where the United States may continue to fail. The enforcement of public health ordinances resurrects age-old tensions regarding who is worthy of public sacrifice and public investment. This fight has never been race-neutral. In a country built on a political economy that racially orders rights and resources, life and liberty have always been racially distributed as well. Dependence on that racialization is the root of our nation’s greatest inequalities, and it may continue to render every one of us, all the more exposed.

Rhea BoydTwitterRhea Boyd is a pediatrician, public health advocate, and scholar who writes and teaches on the relationship between structural racism, inequity, and health.