I found my great-great-great-great-great-grandfather on my mother’s side listed for sale in an old newspaper advertisement: “Stephen, 50, sawyer and sailor.” The announcement, headlined with the word “SLAVES” in bold capital letters, stated that he was to be auctioned off at Maspero’s Coffee-house in New Orleans on February 3, 1820, along with the other property that had belonged to Francis Cousin, a wealthy white plantation owner in St. Tammany Parish.

Cousin died the previous year, and the executor of his large estate placed a paid announcement in the January 4, 1820, edition of the Orleans Gazette and Commercial Advertiser that all of the planter’s earthly possessions would be sold to the highest bidder: the 4,000-acre farm, the furniture, the two sailing ships, and the 760 heads of horned cattle. Among the “moveables and immoveables” in the estate’s inventory were more than three dozen Black human beings—children, women, and men—including my ancestor, Stephen (or Etienne, as he was most often called in French-speaking Louisiana).

For the benefit of potential buyers, the ad provided a short description of each of the enslaved people in Cousin’s estate. They included: “Hector, a black lad of 14 and very sprightly,” “Charlottine, a black wench of about 32, and her three children, Cora, 6 years, Delphina, 3 years, Corma, 11 months old,” and “Friday, 40; woodcutter,” who “has had his thigh broke when he was young, but he can work.”

Stephen and the people sold with him spent their lives laboring without compensation from sunrise to sunset six days a week, solely for the economic benefit and comfort of their masters. They risked whippings or death if they attempted to escape, yet as they stepped up to the auction block before potential bidders, each of them knew—if they were old enough to be aware of what was happening—that they could be sold to a master who would permanently separate them from their loved ones. Prospective buyers looked in their mouths, felt their bodies—even groped the breasts of women and girls—as they inspected the “merchandise.”

Like most Black Americans, I trace my lineage to people who were kidnapped from Africa and forced to serve white masters, generation after generation. Over the years, I have made innumerable trips to parish courthouses and archives, and I have spent countless hours poring over records. Because of this work, I am fortunate to have been able to track down the forgotten names of a few of my shackled forebears. Stephen is one I have confirmed because he was the patriarch of a family of sailors in southern Louisiana, but in all likelihood several of the others listed in Cousin’s inventory were Stephen’s relatives—and thus also my ancestors.

As both a journalist and a descendant of slaves, these historical injustices are personal for me. I want my forebears to receive their proper respect at last. I also want my profession to acknowledge and atone for its racist roots. Yet of the 20 companies I reached out to for this piece, representing dozens of newspapers, only a handful saw fit to even acknowledge—let alone apologize for—their complicity in America’s racial terror.

This article focuses on print journalism, for several reasons. First, although scholars believe that early US radio journalists announced the time and location of lynchings, few recordings of those broadcasts have survived. In 1936, the Omaha station WOW sparked protest when it broadcast the slavery-era song “Run, Nigger, Run” for six weeks each Saturday after midnight (presumably to terrorize Black motorists on the streets after dark). We know of the incident now in large part because of its coverage in the newspapers.

Second, although there are countless instances of racism in broadcast media—from Amos ’n’ Andy and Mickey Mouse to the white supremacist TV ads for Democratic US Senate candidate J.B. Stoner in 1972—the most numerous and egregious examples come from the print press, which in many cases profited not only from offensive or condescending language and depictions but also from the traffic in and murder of human beings.

Although it’s rarely discussed, even at elite journalism schools like the one where I teach, a significant portion of America’s existing news business was built on slavery and other forms of racist terror. While the Orleans Gazette ceased publication in the 19th century, there still exist numerous newspapers that once sustained themselves by selling advertising space to slaveholders who wanted to recapture runaways or who sought to sell their human property at auctions like the one where my ancestor Stephen once found himself. These outlets include some of America’s oldest periodicals, both Northern and Southern: The Baltimore Sun, the New York Post, The Times-Picayune (New Orleans), The Augusta Chronicle (Ga.), the Richmond Times-Dispatch (Va.), The Commercial Appeal (Memphis), and The Fayetteville Observer (N.C.), among others. A typical example of such an advertisement is one printed in the July 3, 1805, edition of the New-York Evening Post, the predecessor title of today’s New York Post, which reads, “TWENTY DOLLARS REWARD. RAN-AWAY from the subscriber on the 30th of June, a negro man named Joseph, aged about 30 years.” Or this one printed on April 18, 1854, in The Daily Picayune, the predecessor title of the present-day Times-Picayune, which reads, “For Sale…A likely lot of SLAVES, consisting of men, women and children, which I will sell low for cash or city acceptance.”

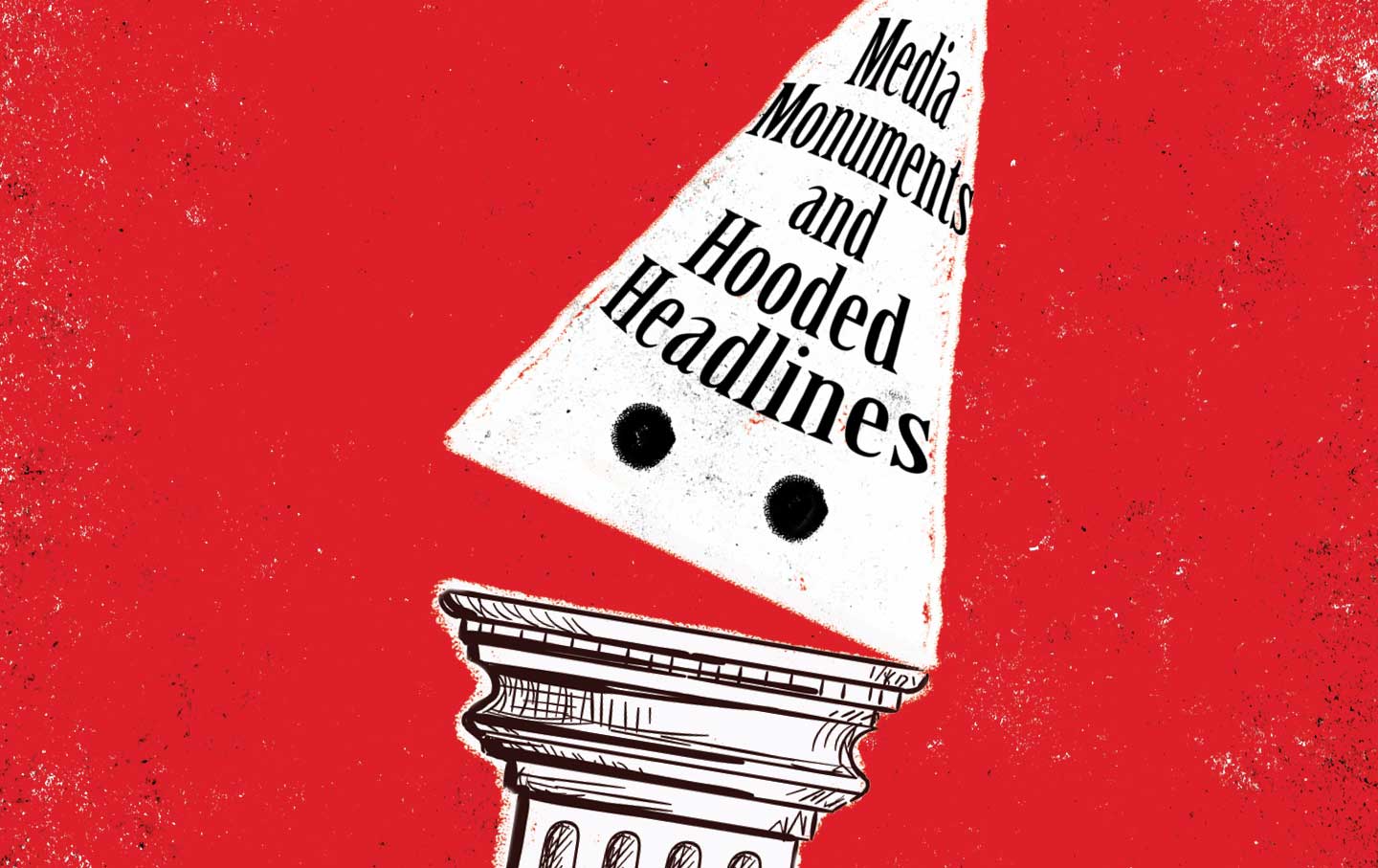

Blood money: Notices for the sale of human beings, or seeking enslaved persons who escaped, were an important source of advertising revenue.

There is no known record of the sights and sounds of the 1820 auction where Stephen was sold, but descriptions of similar auctions were published elsewhere. Such accounts were usually provided by Northern abolitionist outlets like Frederick Douglass’ Paper and The Anti-Slavery Bugle, but in a letter published in The Washington Union on November 14, 1857, the pro-slavery journalist Edward A. Pollard describes witnessing the auction of several families in Macon, Ga., and even praises the virtue—the “humanity”—of the slaveholders:

During the sale referred to, a lot was put up consisting of a woman and her two sons, one of whom was epileptic (classified by the crier as “fittified”). It was stated that the owner would not sell them unless the epileptic boy was taken along at the nominal price of one dollar, as he wished him provided for. Some of the bidders expressed their dissatisfaction at this, and a trader offered to give two hundred dollars more on condition that the epileptic boy should be thrown out. But the temptation was unheeded, and the poor boy was sold with his mother. There are frequent instances at the auction-block of such humanity as this on the part of masters.

The chaos and cruelty of the Trump administration reaches new lows each week.

Trump’s catastrophic “Liberation Day” has wreaked havoc on the world economy and set up yet another constitutional crisis at home. Plainclothes officers continue to abduct university students off the streets. So-called “enemy aliens” are flown abroad to a mega prison against the orders of the courts. And Signalgate promises to be the first of many incompetence scandals that expose the brutal violence at the core of the American empire.

At a time when elite universities, powerful law firms, and influential media outlets are capitulating to Trump’s intimidation, The Nation is more determined than ever before to hold the powerful to account.

In just the last month, we’ve published reporting on how Trump outsources his mass deportation agenda to other countries, exposed the administration’s appeal to obscure laws to carry out its repressive agenda, and amplified the voices of brave student activists targeted by universities.

We also continue to tell the stories of those who fight back against Trump and Musk, whether on the streets in growing protest movements, in town halls across the country, or in critical state elections—like Wisconsin’s recent state Supreme Court race—that provide a model for resisting Trumpism and prove that Musk can’t buy our democracy.

This is the journalism that matters in 2025. But we can’t do this without you. As a reader-supported publication, we rely on the support of generous donors. Please, help make our essential independent journalism possible with a donation today.

In solidarity,

The Editors

The Nation

Anti-Blackness has been at the heart of American society since this nation’s founding. It was codified in the original US Constitution, which stated that an enslaved person would count as three-fifths of a white person for the purposes of taxation and representation. Two decades into the 21st century, more than a century and a half since the legal abolition of slavery, Black Americans continue to experience the long-term impact of slavery and other forms of racist terror—much of it promoted and perpetuated by the news media.

There are a few examples, mostly in the North and West, of long-lived newspapers that, as far as I can tell, did not publish ads for slaves, including The New York Times. But even many of those papers championed racist violence in other ways, including defending the legality of slavery, encouraging mob lynchings, advocating racial inequality, celebrating segregation, and characterizing Black people and other people of color as brutes, rapists, and other types of criminals. Disgracefully, these publications include some of the country’s most revered: The New York Times, The Washington Post, the Los Angeles Times, The Atlanta Journal-Constitution, The Cincinnati Enquirer, The Courier-Journal (Louisville, Ky.), The Post and Courier (Charleston, S.C.), The Birmingham News (Ala.), and The St. Louis Post-Dispatch, to name just a few.

In a September 24, 1851, editorial, The New York Times condemned the white abolitionist William L. Chaplin as a man “of diseased sympathies” for helping two enslaved people in Washington, D.C., escape from their master, Robert Toombs, a Georgia congressman and future Confederate secretary of state. The editorial stated, “This man, Chaplin, through some process of reasoning or other, believes it to be his duty to aid slaves in gaining their liberty; and addicts himself, therefore, to enticing them to run away.” It concluded, “His offence is clearly theft, for they are the legal property of their masters.”

When I was a boy, my grandmother told me the story of a Black man who had been dragged through the center of Slidell, La., the town where we lived. It was a story she had overheard her parents talk about in hushed tones. Years later, I found the news accounts. On August 6, 1914, The Times-Picayune published an article that described how an angry mob “of unknown persons” had tied a Black murder suspect to the back of a car and dragged him until he was dead. The headline of the article, “Tie Negro to Auto, Then Throw on Speed,” sounds like a command to readers. Town officials conducted no investigation to discover the identity of the killers.

Three years earlier, the same paper reported that “a mob of 200” had lynched Sam Cooley, a Black suspect in an attempted rape in the nearby town of Pearl River, La. According to the 1910 census, the white population of Pearl River was only 238, suggesting that nearly every white resident had turned out to seek vengeance on Cooley.

Papers not only reported on lynchings in a manner that implied or explicitly indicated approval, they even published ads from racial terror groups. In March 1868, during the Reconstruction era, the Richmond Dispatch, the predecessor of today’s Richmond Times-Dispatch, accepted paid advertising from the Ku Klux Klan, which it ran on its front page.

In some cases, journalists traveled with mobs to the scene of imminent lynchings and wired back observations as the crime took place. On November 16, 1900, a Colorado mob of 300 white people executed a Black teenage murder suspect who appeared to have a mental disability. “Boy Burned at the Stake in Colorado,” The New York Times announced on its front page the next day. “A number of reporters and telegraph operators with portable instruments were with the lynching party. The wires were cut, and reports of the lynching, in the form of bulletins, were telegraphed direct from the scene of the occurrences,” the article stated. It then provided graphic details of the killing: “What agony the doomed boy, who was only sixteen years old, suffered while the flames shriveled up his flesh could only be guessed from the terrible contortions of his face and the cries he gave from time to time.” The account ended with a summary of what the writer clearly considered the enlightened point of view: “The general sentiment expressed approves the execution of the negro, but deprecates the method adopted.” Similarly lurid reports, which would have attracted curious readers and meant greater profits from newspaper sales, were also published and reprinted nationwide by the Associated Press, the Los Angeles Times, The Boston Globe, the Chicago Tribune, the San Francisco Examiner, and dozens of others.

From the post-slavery period until the early 20th century, sensational accounts of Black suspects being taken from local jails by white mobs and shot, hanged, burned, or dragged through town were a regular feature of the popular press. Most often the suspects were Black men accused of raping white women, but the lynching victims also included Black women and children, who were charged with a variety of crimes or misbehavior, including stealing livestock and “insulting whites”—or sometimes nothing at all.

Prominent voices pointed out the newspapers’ complicity in lynchings as far back as the 19th century. “The American press, with few exceptions…has encouraged mobs, and is responsible for the increasing wave of lawlessness which is sweeping over the States,” the famous Black investigative reporter Ida B. Wells wrote in a letter published in The Washington Post on July 3, 1893. Wells had written to the paper in response to a Post editorial criticizing her anti-lynching campaign.

Get unlimited access: $9.50 for six months.

Such coverage helped to justify and to glorify racial terror lynchings—a fact recognized at the time. In 1920, the St. Louis Post-Dispatch published a letter from a reader who remarked, “Through your columns I wish to ask the reporters on the daily papers if they do not recognize the responsibility that rests upon them when…they point suspicion toward negroes in cases where white women are involved?”

American papers typically assumed that the victims of lynchings were guilty and deserved their fate, publishing boldface headlines such as “NEGRO BRUTE LYNCHED” (The Washington Post, August 2, 1899); “A FEARFUL RIDE OF DEATH. SPEEDY JUSTICE METED OUT TO A KANSAS BRUTE” (The New York Times, January 31, 1887); and “DESERVED HIS FATE. A Worthless Negro Shoots a Young Man, and Is Riddled With Bullets by the Crowd” (The Cincinnati Enquirer, August 8, 1882).

Aside from being morally bankrupt, these news stories were often inaccurate. Mobs regularly lynched the wrong person, as was discovered in many instances after the real culprit confessed. Yet even in such cases, it was uncommon for lynchers to receive punishment of any kind.

“In practice, lynchers enjoyed immunity from state or local prosecution,” David Garland, a professor of sociology at New York University, wrote in 2005. Lynching “was usually regarded with broad approval by large sections of the communities in which the lynchings occurred, and it was tolerated (and often applauded) by local politicians and law officers.”

“Local newspapers (and later radio stations),” Garland observed, “would announce that a lynching was imminent, stating the likely time and place.”

On March 18, 1886, to cite one example, The Atlanta Constitution announced, “WILL BE LYNCHED TONIGHT. A Fiendish Crime Reported From Tennessee.”

A 2017 study by the Equal Justice Initiative documented “4,400 racial terror lynchings in the United States during the period between Reconstruction and World War II.” In an 1894 speech, Wells said that according to her own investigations, “less than one-third” of lynching victims had been charged with sexual assaults. “Only charged, mind you,” she added, “and in many cases the real culprits were white people, who found their poor colored brothers convenient scapegoats upon whom to saddle their misdoings.”

Responding to her activism, The New York Times lambasted Wells as a “slanderous and nasty-minded mulattress” in an editorial that year. In addition, the paper described rape as a “crime to which negroes are particularly prone.” To be fair, the Times more recently published essays by Brent Staples and Charles Seguin criticizing its history of supporting lynchings. However, it has never issued an official apology for its previous coverage or editorial views.

Of course, media culpability for racism goes far beyond slavery and lynching. In the 1960s, The Birmingham News was still proudly celebrating the Confederacy and the legal segregation of the races. On a cold day in 1963, the paper’s lead story reported on the inauguration of segregationist George C. Wallace as Alabama’s governor, noting, “Shivering throngs cheer Wallace…. Temperatures were below freezing as the Heart of Dixie played and marched for more than four hours…on a day when the breeze was blue and the skies were Confederate gray.”

Preston Porter Jr., shown holding a Bible in this photograph from the San Francisco Examiner, was burned alive near Limon, Colo., in 1900.

In response to my inquiries, several news organizations have acknowledged their disgraceful history but declined to apologize.

The Associated Press expressed “regret” over the racism of its past coverage and vowed to do more research into its own history. “We know of no instance in which the AP deliberately promoted racist violence,” wrote John Daniszewski, the agency’s vice president and editor at large for standards. “However, the AP reported on lynching and other forms of racial violence over many years, sometimes in disturbing detail, with flaws and omissions. These shortcomings clearly reflected the attitudes and prejudices of the era in which these reports were written. But that is no excuse, and we regret them.”

On the AP’s coverage of the Colorado murder of Preston Porter, a Black teenager, in 1900, Daniszewski acknowledged that “the justification for the killing went unchallenged in this story and the supposed guilt of the victim was taken for granted.” He added that the AP was now “conducting further research on its own reporting from earlier times.”

A New York Times spokesperson said the organization “believes that owning up to moments when our journalism falls short is an essential part of demonstrating our commitment to fairness, accuracy, and integrity, and we’ve done it repeatedly over time. For example, with the Overlooked project: The Times acknowledges that since 1851, obituaries…had been dominated by white men, and we have since published more than a hundred obituaries of remarkable people, including celebrating the life and accomplishments of Ida B. Wells.”

A spokesperson for Tribune Publishing, the owner of many papers including The Baltimore Sun, the Chicago Tribune, and the Hartford Courant, said, “We continue to have discussions about Baltimore Sun Media’s past,” adding that they had published two editorials “detailing our past coverage and business practices and acknowledging our publications’ actions.”

Caroline Harrison, the CEO of Advance Local, parent company of The Birmingham News, said, “It is true that at times during its more than 130-year history, The Birmingham News has published material that falls far short of the anti-racist standards that are now a core part of our culture. Today, the paper, like all of our Alabama journalism, publishes work that regularly shines a light on day-to-day and systemic racism and oppression in our society, seeking to advance equitable opportunity.”

Maribel Perez Wadsworth, president for news at the USA Today Network, issued a statement on behalf of The Cincinnati Enquirer, The Commercial Appeal, The Fayetteville Observer, and the other Gannett-owned papers mentioned in this article. “Journalism plays an integral role in helping to expose injustices and right wrongs, and that includes important introspection into our own histories,” she wrote, stopping short of an apology but promising more inclusive coverage in the future.

The Washington Post and The Augusta Chronicle declined to comment. The New York Post, The Post and Courier, the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, the San Francisco Examiner, The Atlanta Journal-Constitution, and The Times-Picayune/The New Orleans Advocate did not respond to repeated requests for comment.

In a significant development, however, The Boston Globe announced in March that it is joining forces with Boston University’s Center for Antiracist Research to found The Emancipator, a new publication dedicated to racial justice. Named after the first antislavery newspaper in the US, the project is the brainchild of Ibram X. Kendi, a professor at the university and the author of How to Be an Antiracist, and Bina Venkataraman, the Globe’s editorial page editor.

“I think it’s good for newsrooms and legacy journalistic institutions, like all civic organizations, to reckon with sins of the past if they can establish that doing so will restore trust and credibility and move their organizations forward,” Venkataraman told me. “Just as important, if not more so, is for news organizations to think anew about how they cover all kinds of communities and reach all kinds of audiences, and about how they cover and reckon with the most pressing problems of our time, which, of course, includes racism and the legacy of slavery in American society. The Emancipator is an attempt to do that.”

Icall on all American news organizations—including TV, radio, and social media outlets—to investigate, acknowledge, apologize, and make amends for their role in disseminating racist ideas and profiting from racist violence.

Apologies, of course, are not sufficient, but even those have been so rare that the number of prominent newspapers that have issued anything like a full accounting of their role in promoting racist violence can be counted on the fingers of one hand. In 2000, the Hartford Courant apologized for publishing ads for “the sale and capture” of slaves. National Geographic apologized for its history of racist coverage in 2018. The Montgomery Advertiser apologized for promoting lynching that same year, and in 2020, the Los Angeles Times and The Kansas City Star issued apologies for more than a century of racist coverage.

In the Star’s apology, “The truth in Black and white: An apology from The Kansas City Star,” its editor, Mike Fannin, wrote, “Today we are telling the story of a powerful local business that has done wrong. For 140 years, it has been one of the most influential forces in shaping Kansas City and the region. And yet for much of its early history—through sins of both commission and omission—it disenfranchised, ignored and scorned generations of Black Kansas Citians. It reinforced Jim Crow laws and redlining. Decade after early decade it robbed an entire community of opportunity, dignity, justice and recognition. That business is The Kansas City Star…. We are sorry.”

Fannin told me that it was important not only to acknowledge the past but to apologize, without being defensive, because of the paper’s history of alienating Black residents—even excluding them from the obituary section. “I saw an opportunity to gain trust in the Black community here in Kansas City,” he said. Since the apology, which followed months of interviews and “digging through microfilm,” Fannin said he realized that “this was something that the community wanted to be told.” His message to America’s papers: “Think about the people you’re writing for.”

Many of our most storied news outlets have not apologized or have even denied their role in sustaining racial inequality. In 2000, The Baltimore Sun, which ran advertisements for runaway slaves to help build its business, published an op-ed arguing that “1800s acts don’t need apologies.”

But history must be acknowledged before justice can be done. Journalists and journalism as a profession need to take a serious look at our own contributions to racial inequity. The time is now.

Channing Gerard JosephChanning Gerard Joseph teaches at the University of Southern California’s Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism.