Georgia’s Republican governor, Brian Kemp, said that 345,000 people would enroll in the state’s Medicaid program, which has strict work requirements—so far just 5,118 have.

In 2023, when Georgia launched a Medicaid program that was tied to a strict work requirement, Republican Governor Brian Kemp framed it as a way to help people get healthcare coverage. He made this claim even though the state was—and still is—refusing to expand the program under the Affordable Care Act. The new plan would be “innovative,” Kemp said, putting “Georgians and their access to care first.” He said that 50,000 people would join in the first year and that eventually 345,000 eligible people would enroll.

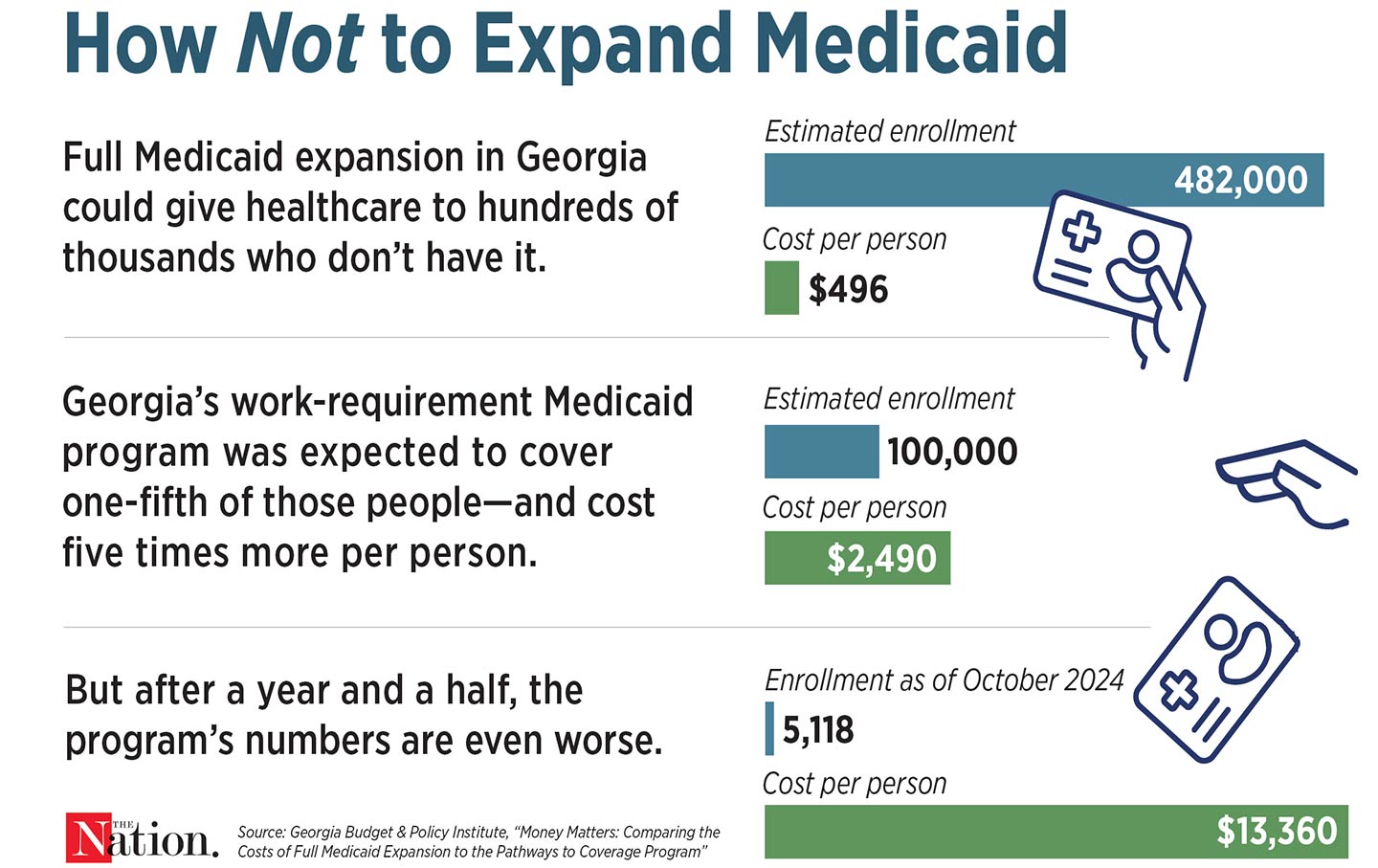

A year and a half later, his promises haven’t been borne out: As of the end of October, just 5,118 people were enrolled in the state’s Medicaid work-requirement program—that’s 5 percent of the people who said they wanted to sign up.

Part of the problem is that Georgia’s work requirement is particularly harsh. As in other states that have proposed forcing Medicaid recipients to prove that they work, people in Georgia who earn no more than $31,200 for a family of four and want to enroll in the new program have to regularly report that they are either working, going to college, attending job training, or volunteering at least 80 hours a month. But unlike those of other states, Georgia’s rules apply to people as old as 64 as well as to those who are caring full-time for their children or for other relatives, don’t have transportation, or are dealing with drug addiction. Other states have also proposed giving people a few months as a grace period to fulfill the requirements before losing coverage; Georgia can yank it after two months.

The state has also made it difficult for people to enroll. Georgians need to make their way through “lengthy questionnaires and technical language,” The Atlanta Journal-Constitution reported. The tools to upload documents are hard to use; sometimes the website just stops working. In June, 1,459 people tried to enroll in the program but couldn’t, because they were unable to report their work hours to qualify for coverage.

For this, the state is spending a fortune. A year after its launch, the program has cost nearly $58 million, most of which went to administration and consulting fees, not medical expenses.

Georgia could have simply expanded Medicaid to all low- and moderate-income residents, which would have cost the state less and gone a lot further toward Kemp’s purported goal of expanding access to care. Georgia’s regular Medicaid program is already one of the stingiest in the nation: Parents can enroll only if they make less than $10,000 a year for a family of four, and adults without children can’t join at all. If Georgia had expanded Medicaid, 359,000 people would be able to enroll. It would also be far cheaper: Instead of spending $2,490 to enroll each of the expected 100,000 people in the work-requirement program, the state would pay just $496 per person in fully expanded Medicaid. But in March, state lawmakers defeated a proposal to expand Medicaid.

The high cost and ineffectiveness of the work-requirement plan shouldn’t have surprised Governor Kemp. In 2018, Arkansas became the first state to institute a work requirement for Medicaid enrollees. The program had no discernible impact on employment, and more than 18,000 people lost their Medicaid coverage because they couldn’t meet the requirements or finish the paperwork. It also cost the state about $26 million. Such programs in other states have had even higher price tags; in 2019, the federal government estimated that Kentucky’s work requirement would cost the state $272 million.

But even in states that have adopted Medicaid expansion and haven’t implemented pointless work requirements, paperwork prevents millions of Americans from accessing healthcare. Early in the pandemic, Congress passed legislation barring states from kicking anyone off during the public health emergency. That ended in April 2023, and states resumed making people regularly prove that they are still eligible. More than 25 million people have lost their coverage since then, nearly 70 percent of those because of procedural or administrative problems.

The pandemic proved that we could simply keep people enrolled in Medicaid, giving them access to care that lowers medical debt, improves health, and reduces deaths. During the public health emergency, more than 21 million people signed up when paperwork was halted. But the country remains obsessed with making people prove that they’re worthy of coverage instead of just helping them stay healthy.

Bryce CovertTwitterBryce Covert is a contributing writer at The Nation and was a 2023 Reporter in Residence at Omidyar Network.