Tyree Nichols called for his mother.

The 29-year-old was on his way from work in Memphis when the police stopped him. The body-cam video showed a group of officers brutally beating him—kicking him, pepper-spraying him, even delighting in his pain. By the time his family got to him, he lay unrecognizable in a Memphis hospital, his face bruised and bloated. Nichols died from his injuries several days later.

Just three years earlier, during the height of the 2020 coronavirus pandemic, George Floyd called for his mother too. He was pulled out of his parked car and handcuffed after a store clerk reported that he had used a counterfeit $20 bill. Floyd was forced to the ground face down.

Minneapolis police officers stood by and watched as one of their own pressed his knee on Floyd’s neck for more than nine minutes, killing him. Bystanders pleaded with the officers as they saw Floyd take his last breath and lie limp on the hard concrete street.

The list is long:

Trayvon Martin

Eric Garner

Tamir Rice

Alton Sterling

LaQuan McDonald

Botham Jean

Ahmaud Arbery

Ronald Greene…

Young men who were gone too soon.

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →

In each case, a mother and Black women nationwide, stood up, marched, protested, cried, and sought justice for these Black men who were sons and fathers and brothers and uncles.

We will never know what these young men could have been or what they could have done or how they could have used their skills, talents, and gifts to make this world a better place.

But we do know that Tyree Nichols called for his mother, and that George Floyd did too.

In their time of pain and distress, as they felt their lives slipping away, they reached out for their mother—the person who gave them life, their first provider and protector.

Imagine giving birth to a son, raising him, and having his life violently snatched away.

The hurt is unimaginable.

I can imagine that Emmett Till called for his mother too.

The 14-year-old from Chicago was visiting his cousins in Mississippi in the summer of 1955. They stopped for some candy at Bryant’s Grocery Store in the tiny town of Money. As they left, Till allegedly whistled at a white woman, Carolyn Bryant (she died this April 25 at age 88).

This was taboo in Mississippi in 1955.

Racism ran rampant in the state. Segregation was the law of the land. Jim Crow laws were strictly enforced. There were whites-only restaurants and hotels, water fountains, theaters, schools, and stores. Hate filled the state. White men called Black men “boy,” and Black people were relegated to the back of the bus. Black people couldn’t look white people in the eyes or walk on the same sidewalk. Black people had to call white people, even white children, “sir” and “ma’am.”

Neighborhoods were segregated, usually by railroad tracks, and there were places Black people just couldn’t go after sundown or they would find themselves in trouble or not seen the next day.

This was the environment Emmett Till found himself in, in 1955.

On August 28, 1955, several days after Till’s visit to the Bryant store, two men—Carolyn Bryant’s husband, Roy Bryant, and his half-brother J.W. Milam—kidnapped Till from his uncle’s home in the middle of the night.

They took him to a shed and tortured the young 14-year-old Black teen.

They gouged out one of his eyes.

They shot him in the head.

They used barbed wire to tie a 75-pound cotton gin fan around his neck.

Then they dumped his brutally beaten body in the river.

Three days later, Till’s mutilated body was found in the Tallahatchie River.

He was so disfigured that he could be identified only by a ring.

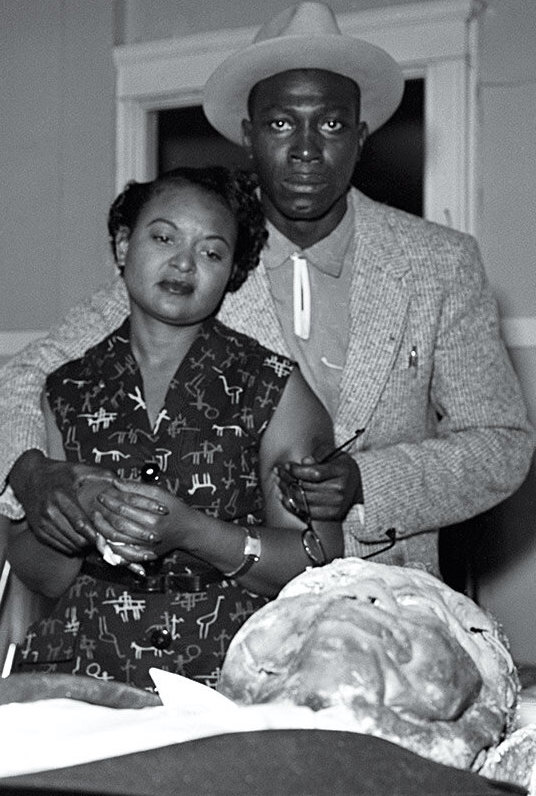

Mamie Till-Mobley, Till’s mother, insisted on having her son’s body flown back to Chicago. Then she insisted on an open casket to “let the world see what I have seen.”

Jet magazine published a photo of Till’s mutilated body on its cover and thousands lined the streets of Chicago for his funeral.

An all-white jury found Bryant and Milam not guilty of Emmett Till’s murder. They later confessed and recounted the gruesome attack in Look magazine.

No one was ever convicted for the murder of Emmett Till.

His mother, Mamie Till Mobley, died in 2003 without ever seeing her son’s killers brought to justice.

Nevertheless, the lynching of Emmett Till reverberated around the world.

Rosa Parks said she refused to give up her seat on a Montgomery, Ala., bus in December 1955, because she was thinking of Emmett Till. Her quiet resistance helped spark the modern-day civil rights movement.

Mamie Till-Mobley was one of the first mothers to seek justice for her son in the long line of mothers that would come years later.

If it weren’t for Till-Mobley’s insistence on an open casket, the world wouldn’t have known Emmett Till’s name. If Till’s mother had not sought justice for her son, the world wouldn’t have known the kind of hate that filled small Mississippi towns and that would kill a 14-year-old boy.

Till would have been one of the many nameless, faceless Black men who were found hung from trees, floating in rivers, or buried in earthen dams. One of the many Black men who disappeared suddenly in the Deep South, never to be heard from again and whose deaths never made the newspapers.

No, that would not be the fate of Emmett Till.

He would not be forgotten.

He would be front-page news.

People would know his name.

He would not die in vain.

His mother would make sure of it.

Mamie Till-Mobley’s voice was strong. It was persistent. It was relentless.

Indeed, it was because of Mamie Till-Mobley’s voice that we know Emmett Till.

She was one of the first women fighting for justice for Black men, but she would not be the last.

No, there was no body-cam video or cell phone recording of Till’s lynching. There were no bystanders pleading for his life. We will never know how scared Till was, the fear that rippled through his body. He was afraid. Yes. And he probably called for his mother.

And his mother made sure the world knew his name.