The Mountain West’s Mega-McMansion Problem

The rich have turned the region into “ultra-exclusive enclaves,” creating hazardous living conditions for everyone else.

Josue Moreno is a manager at an excavation company in Jackson, Wyoming. Sitting at a table outside the Virginian saloon, a short drive from the center of town, a few months back, the 27-year-old sipped a beer as he discussed how hard it is now to survive in a city that is rapidly becoming unaffordable to all but the wealthiest residents. “The past five years have been crazy,” he says, referring to the latest in a seemingly endless cycle of real estate booms in the American West since the migrations of the 19th century. “The town has changed immensely.”

In many ways, the story of states such as Wyoming is a story of displacement: Native American tribes violently pushed off of their land; westward migrants seeking their own slice of the American dream who were, in turn, jostled aside by ruthless mining interests, railway corporations, and the like. State legislators throughout the West have tended to work in unholy alliance with wealthy real estate lobbies. And the result has been a constant churn—one that, in recent years, has accelerated in places like Jackson as an influx of wealthy people from around the country has caused housing prices to soar.

To get by, Moreno shares a small apartment—monthly rent: $3,600—with his younger brother, but he worries that, with rent increasing by 20 percent per year, he will soon be priced out. And his situation is actually better than most in his immediate world. Moreno says that of all the employees at his company, only he and one other person live in town. Everyone else commutes, driving miles over treacherous mountain passes that close frequently in the winter because of snow and avalanches, while paying steep gas prices for their troubles. One employee makes the trek from a town 76 miles away.

These circumstances have made it hard for Moreno to hold on to workers, in whom he has invested thousands of dollars and months of time training. “Housing makes it into a pain keeping people happy at work,” he says. “Every year, you have to give three-dollar, four-dollar, five-dollar [an hour] raises or it doesn’t pay them to work. It’s a hazard. I’ve trained over 100 people. You know how many have stayed? I’d say 10.”

The rest have abandoned the job, and Jackson, for towns that remain more affordable—for now.

For centuries, America’s moneyed elite have parlayed their wealth into land ownership, often buying acreage on a scale almost inconceivable in other countries. Indeed, it was a donation of 32,000 acres from John D. Rockefeller Jr. to the federal government in 1949 that led to the expansion of Grand Teton National Park to its modern borders, which Jackson abuts.

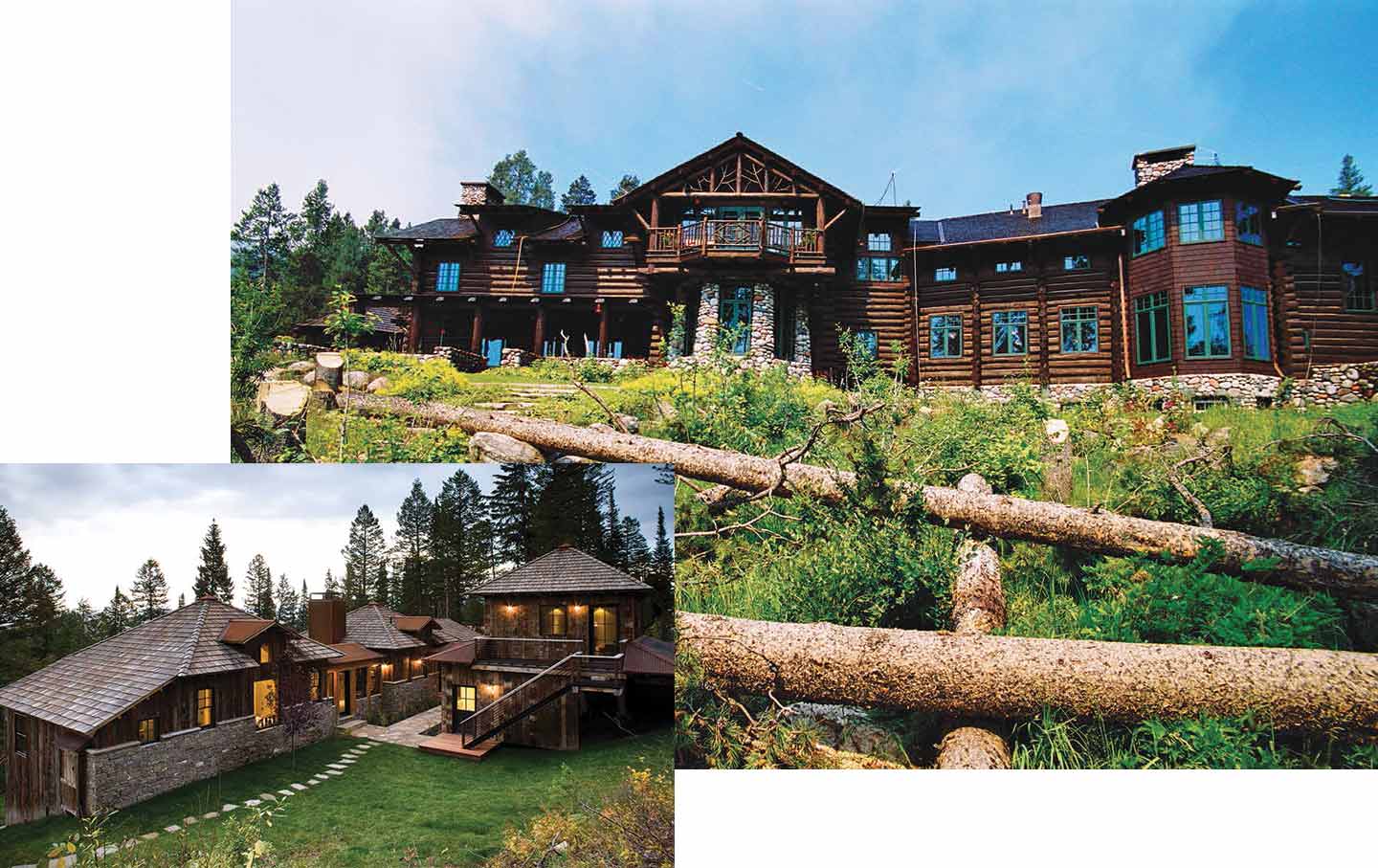

In recent decades, however, as financial power has concentrated at the top of America’s steep economic pyramid, the Mountain West has acquired a whole new mythos, updated for the high-tech era. The region may still bring to mind cowboy culture and pioneer wagons, but in reality, visitors to its boom towns are more likely to encounter Tesla charging stations and fast-food cafés than an old-fashioned cowpoke. While Ted Turner’s decision to go all-in on ranch life outside Bozeman, Montana, in the late 1980s once seemed like the quirk of an enigmatic billionaire, he’s since been followed by a stampede of tech moguls, telecommunications tycoons, energy bigwigs, and hedge fund managers buying up undeveloped acreage to live on or, in other cases, coming with plans to build high-tech utopian cities or retirement communities that would be governed by their own rules and regulations. Others are hoarding millions of acres of forest and farmland on the assumption that, in an era of climate change and population growth, arable land is likely to become increasingly valuable over the coming decades.

Alongside these ultrarich developers, many more are moving into urban centers, places like Jackson and, more recently, Bozeman as well as bigger cities such as Helena, Montana. In these areas, some are buying up multiple lots where small, relatively affordable homes once stood and building mega-McMansions. These trends, which were massively accelerated by the Covid-19 pandemic and the rise in remote working that followed in its wake, have real consequences for the people living in the region, many of whom can no longer afford to buy a house, let alone find an affordable place to rent.

But the housing squeeze in places like Jackson may come less from the superrich than from the merely prosperous—people like Leslie Bensen, who runs a company in Charleston, South Carolina, that places advertisements inside airports around the country and who recently purchased a “getaway” home in Jackson. Ever since she first visited the region in the 1990s to attend a close friend’s wedding, Bensen had been looking for a retreat in the West. She finally bought one last summer for $4 million. “I paid a lot more than I thought I was going to pay,” Bensen says. “Fortunately, I was able to buy a place that’s new, that’s close to town. I can walk to dinner, shopping, [and] social events from my place.”

Bensen, who loves to hike and fish, plans to live in Jackson during the summer and fall months before returning to Charleston for the winter, when temperatures in Wyoming can drop to a bone-chilling minus-20 degrees. “It’s a personal, special place for me,” she says of Jackson. “I love the outdoors—I know it can never change.”

Bensen’s own changing world is part of what sent her westward. At the height of the pandemic, she says, too many Northerners, with their fast-paced ways, moved to Charleston. They spoiled the flavor of the local culture for her. These days she’s more content in Wyoming, dancing at the Million Dollar Cowboy Bar, its barstools crafted from saddles and its chandeliers from elk horns, or sipping wine at the upscale Bin 22 tapas bar, or ordering from Pearl Street Bagels.

But while Bensen has found a haven in Jackson from the hard-charging Yankees who are changing her hometown, the influx of people like her into her adopted city has created its own destabilizing ripples.

In such places, the word gentrification doesn’t do justice to the magnitude of this shift. In the context of the huge changes to real estate markets and the massive displacement of local workers, a new term is needed. In his book Billionaire Wilderness, Justin Farrell, a professor at Yale University’s School of the Environment, describes an “awe-inspiring concentration of wealth and a canyon-size gap between the rich and the poor,” all of which has led to a wholesale transformation of these Mountain West hubs into “ultra-exclusive enclaves.”

A better word for what is happening in the Mountain West might thus be ultra-gentrification.

Jackson is, in many ways, the sentinel city of this phenomenon, the place where the collateral damage of an unfettered real estate boom is most visible. Since the mid-1980s, when some of the world’s wealthiest people discovered a sleepy ski town and began to turn it into a plaything for the rich and famous, the median home price in Jackson has become increasingly unaffordable for the median income earner.

As a result, Jackson has been heading toward grotesque inequality, largely the result of the ballooning fortunes of the newcomers to town over the past few decades. Today, the average income in Teton County, which includes Jackson, is around $200,000, with some estimates putting it far higher.

Moreno recalls clients he has worked for who spent millions of dollars redoing their homes, only to change their mind at the last minute and spend millions more taking their home renovations in a totally different direction. “Dude,” he says, “the amount of money in this town is amazing. There’s no other way to put it.” The downside, of course, is that the housing needs of the non-wealthy get trampled.

Similar trends hold throughout much of the West. In 2008, the mismatch between supply and demand in housing worsened as development ground to a halt during the financial crisis. That’s when many Western cities, from Los Angeles to Phoenix, San Francisco to Las Vegas, began seeing large-scale encampments made up of the recently dispossessed as well as those who couldn’t find homes to rent or buy in the first place.

The story of how the foreclosure crisis and the collapse in housing development played out in the large cities along the Pacific Coast is a familiar one. But on the ground in smaller communities in the Southwest and the Mountain West, a slow-rolling crisis also picked up pace, a crisis triggered by foreclosures and a collapse in home values and then worsened by the boomerang effect a few years later when a tight market witnessed unprecedented price spikes.

“After the recession, we stopped building—as a county, as a community,” says Bozeman Mayor Terry Cunningham, a former New Yorker who relocated decades ago to indulge his passions for back-country skiing, trail-running, and hiking. “The smaller developers were chased out of the market, many never to return. Year after year, we were digging the hole deeper.”

With the coming of Covid-19, that trend accelerated. “Covid was the kerosene on the fire,” Cunningham says. Affluent families, flush with tech dollars, crypto fortunes, and booming energy investments, cashed out their real estate in beleaguered big cities and bought up, or built from scratch, beautiful mansions in Teton County, in Bozeman, in Boise, Idaho—anywhere with clean air, lots of open space, and public areas that weren’t yet inundated with unhoused people experiencing a multitude of health conditions, including addiction and other mental health disorders. With the arrival of Zoom and other videoconferencing technologies, they were able to set up shop and work remotely from their modern-day castles. Hell, they could even make billion-dollar financial deals while hiking their favorite mountain trails.

As a result, says Jonathan Schechter, a Yale-educated management consultant and a member of the Jackson Town Council, “the umbilical cord that connects where you live and where you work is getting stretched and frayed and cut. Someone who’s a waiter here cannot compete against a hedge fund manager who’s moving here to take advantage of the tax situation.”

Every $100 increase in rent in a given market, the US Government Accountability Office calculated in 2020, leads to a 9 percent rise in local homelessness.

“It drove prices through the roof,” says Kurt Harland, a local Berkshire Hathaway real estate agent, sitting in his office on the corner of Jackson Square. “And really, prices have not backed up much since the Covid high. Market prices have doubled. Many of the workforce employees can’t afford to buy.”

The Teton Region Housing Needs Assessment, conducted in 2022 with the support of Teton County in Idaho and Teton County in Wyoming, found that Wyoming’s Teton County needed to build 5,000 affordable homes to meet the demand, and that each home would have to be subsidized with at least half-a-million dollars to render them even remotely affordable. Put another way, the county’s housing market was so out of whack that it would need $2.5 billion in subsidies to allow its residents to live anywhere near their places of employment. In a state where the conservative Legislature has barred local governments from implementing a real estate transfer tax, which could be used to build up trust funds for subsidizing affordable housing, such investments are as likely as the local buffalo learning to fly.

Randy Carpenter sits at a table in one of the thriving new cafés on Main Street in Bozeman, one of Montana’s largest cities and just a 48-minute jet hop across the Grand Tetons from Jackson. The café’s menu is rife with fancy espresso drinks and pastries, its walls lined with modernist art.

Carpenter, who works as a city planner and is the director of the environmental group Friends of Park County, has watched anxiously as the ultra-gentrification trend that swept through Teton County has played out in Bozeman. “The connection between income and home prices gets broken—and that’s where we’re at,” Carpenter says as he sips his espresso drink and leans back into a heavy stuffed leather chair. “Median incomes don’t reflect median prices in the way they used to.”

A decade ago, homes here went for a couple hundred thousand dollars; now many are selling for north of $1 million—in a state where the law permits some tipped employees to be paid as little as $4 per hour. And while planners like Carpenter have joined forces with local advocates and city officials to try to offset this imbalance by attempting one policy intervention after another, the conservative state Legislature has consistently blocked these efforts. In 2023, the Legislature passed a statewide ban on rent control, preventing liberal cities like Bozeman from placing any limits on commercial or private rents. And, as in Wyoming, the state has barred, this time through a constitutional amendment, any creation of local real estate transfer taxes that could be used to help solve the burgeoning housing crisis. Far from being an inevitable development, the work of the market’s invisible hand for which no one is to blame, the housing crisis in this part of the country is very much the product of political choices and of conservatives’ fiercely ideological opposition to any effort to make housing more affordable.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →The result is an ongoing stampede toward ever-greater inequality, with the historic old main streets in Bozeman, Helena, and other cities in the region converted into boutique playgrounds for the affluent new arrivals, and with the collateral damage of the changing real estate market being pushed to the margins of these boomtown cities. In Bozeman, previously tranquil streets on the outskirts of the city—past the strip malls and the big-box stores on its northwestern edge—are suddenly lined with RVs, which residents, priced out of the soaring rental market, have converted into makeshift homes.

“I’m on $1,000 a month,” says Chuck, a 68-year-old RV dweller who says that he had to have brain surgery several years ago. No longer able to work as a carpenter, he now lives on disability. “What are you going to afford here?” he adds.

Chuck lives with a cat called Mercedes and a dog named Bentley and spends much of his time sitting outside his RV on a little folding chair, barefooted, in shorts and a sleeveless shirt, turning every couple of minutes to spit into the dirt beside him. When he moved into his RV eight years ago, Chuck says, he was something of an urban camping pioneer, an outlier. Back then, the RV’s engine still worked, and he would drive from one site to the next. These days, the vehicle is immobilized—though at least, using his carpentry skills, he has managed to weatherproof the roof somewhat. It is, however, less of a lonely experience than it used to be. Now he has dozens of neighbors in vehicles lined up along Rawhide Road, Max Avenue, and several other side streets off 19th Street. By 2020, the number of unhoused residents in town had ballooned to 400, from about 100 before the pandemic broke out. Some are simply trying to live as off the grid and under the radar as possible. Others are workers who were priced out of their homes.

When Mayor Cunningham and his colleagues in city government tried to alleviate the problem in Bozeman by proposing inclusionary zoning laws that would require housing developers to include a certain number of affordable units in their buildings, the GOP-dominated state Legislature pushed back, prohibiting cities from imposing any such mandates on private developers.

“It’s a constant battle, being in defensive mode against a constant barrage of legislation that takes away the power of local government,” Cunningham says.

Making matters worse, affluent NIMBYist homeowners and developers, fearing that change would undermine property values and make the building of new homes less profitable, have resisted the city’s updated affordable housing regulations, which provide incentives to developers, in the form of bonuses, tax credits, and less restrictive parking-availability requirements, to build more affordable housing units.

“We were behind on our housing stock before Covid, and our wage growth in Montana was also not keeping up,” says Jennifer Boyer, a commissioner of Gallatin County, which includes Bozeman as well as communities like Belgrade and West Yellowstone, all of which are suffering from the chronic shortage of affordable housing, even while the county has an almost vanishingly low unemployment rate. “And then you add Covid and the mass migration [of remote workers into the Bozeman region], and it just blew up.” In 2021 alone, according to a 2023 housing report by a local realtors’ association, 2,900 people moved into Gallatin Valley. In slightly smaller numbers, that growth trend has continued ever since.

On the campaign trail, as Boyer canvassed voters, she encountered one young family after another who were pulling up stakes and moving on. They had realized, she says, that they could neither afford to pay rent in an out-of-control market nor come up with enough money for a down payment on a house at a time when home prices had doubled and the mortgage interest rate was above 6 percent. She met firefighters and teachers and local government employees living scores of miles from their places of employment, and she encountered others—including, she says, some senior local government officials in smaller towns in her jurisdiction—sleeping in campers because they couldn’t find homes to rent or buy.

“There are people who are in county government, and they’re being priced out,” Boyer says. “And particularly in Bozeman, people are making a very rational decision to live in campers. We have seen the proliferation of urban camping. These folks are working in our community. The vast majority are working people. That has created a tremendous amount of social conflict in neighborhoods that have camper communities near them. There have been significant public health concerns,” she adds, especially over the disposal of waste from the RVs’ septic tanks.

Boyer has watched as the public’s empathy for the campers, which was strong in the early days of the crisis, has largely evaporated. As is the case in homelessness hot spots around the country, she says, “there is much less empathy [these days], and a lot of frustration is happening. We want people to be safe, healthy, and housed. And that’s a very hard thing to accomplish when our social discourse has been so disrupted.”

Not all of the efforts to protect Mountain West communities from ultra-gentrification have failed.

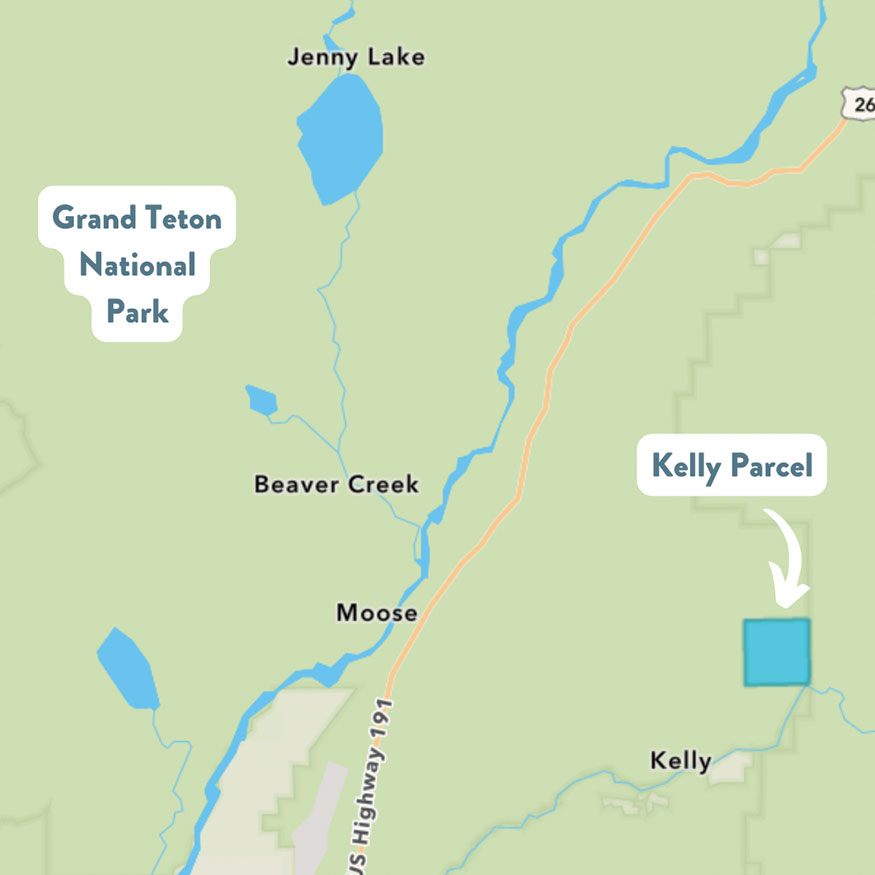

The Kelly Parcel is a stunning 600-plus acres of wilderness on the edge of Grand Teton National Park. The land had been allotted to the state, a legacy of the late 19th and early 20th centuries (when the federal government allotted at least one square-mile parcel of land to Wyoming in every new township, essentially as a land trust that would hopefully accumulate value). Two years ago, the state decided to cash out, hoping to auction off the Kelly Parcel—ideally selling to the federal government, which would incorporate the land into the park system—for a sum in the region of $100 million. The state would then use the proceeds to fund schools, which urgently need the money: Wyoming has one of the smallest tax bases in the US, with no state income tax, no estate tax, no corporate income tax, low property taxes, and strictly limited sales taxes.

But having swung rightward as the political winds brought into power a leadership increasingly hostile to the idea of a redistributive, pro-environment government, the five-member State Board of Land Commissioners in the Office of State Lands and Investments (OSLI) opted not to sell to the National Park Service but instead to pursue the highest bids from the private sector, meaning the land would likely be converted into mega-mansions or into casinos, golf courses, and other playthings for the region’s super-wealthy.

The proposal provoked a furious reaction in liberal Teton County. “It galvanized the citizens of Wyoming,” says Kevin Krasnow of the Jackson Hole Conservation Alliance, referring to the thousands of public comments that were filed in opposition and the planning meetings filled with people angered at the prospect of a land grab by the superrich. “It kicked off amazing resistance from across the state.”

Finally, the OSLI caved, agreeing to spend 2024 negotiating with the feds to sell the land to the National Park Service, which ultimately agreed to make the Kelly Parcel part of Grand Teton.

It was a small victory. But for local progressives, it was at least partly overshadowed by the ever-growing income and housing inequality in their communities, as well as by the fear that a second Trump administration would result in even more attacks on environmental agencies and would further empower those who believe that the private sector is always better than the government at accomplishing any given task. “The free market will never be able to solve the housing problem,” says Clare Stumpf of Shelter JH, a group that advocates for affordable housing. Stumpf used to be a river raft guide and spent her summers sleeping in her car in the parking lot of the rafting company she worked for. “A local worker simply cannot compete with folks who are working remotely, folks who have eight homes.”

Twenty-five miles from the center of Jackson, over the windy, steep, 8,400-foot-high Teton Pass, sits the tiny community of Victor, Idaho (with a population of just over 2,000 people). Victor was founded in the late 1880s, a year before Idaho gained statehood. For most of its nearly 140-year history, it has been a sleepy agricultural community. But now, like its larger neighbors, it has started to see houses selling in the $1 million range, largely as a result of the spillover from Jackson. Even condos in the area are going for $700,000. Still, compared with Jackson, those prices are a steal—and so growing numbers of people are relocating there, creating a real estate boom in the middle of a rural wilderness.

At the chic Butter Café, I meet Tracy Mulligan, a longtime elementary school teacher in Jackson who decided during the pandemic that she’d had enough of working in education and ended up as a barista and manager at the café in Victor.

After her 27 years of teaching, Mulligan’s salary topped out at a meager $56,000. Her younger colleagues were starting out their careers at less than $40,000—nowhere near enough to allow them to afford a home in Jackson. At the café, she earned less; hourly wages for staff start at a lowly $10 an hour.

Mulligan was lucky, however. She had made the leap to Victor years earlier, buying a small ranch house for just over a quarter of a million dollars. During the last eight years of her teaching career, she had done the daily commute over the mountain pass to Jackson. On a good day, the journey was 40 minutes each way; on a bad day, two hours. Now her home had massively appreciated in value, and she loved being what she called a “mountain momma.” Many of her friends weren’t so fortunate: People were doubling and tripling up in small apartments. When they got together at her place to chat, the high cost of housing always came up, as did the unaffordability of childcare, which runs close to $11,000 a year in Wyoming.

“It’s tough,” Mulligan says. “You need to make a certain [income], and [employers] aren’t necessarily in a position to provide that.”

That is, unless you’re lucky enough to qualify to buy one of the handful of affordable housing units going up around Jackson. The affordable housing groups that build these units are subsidized by the donations of the local moneyed elite, and as a result they can sell the homes they build for less than one-third of the market rate.

Joe Stone, an outdoors enthusiast who was paralyzed from the chest down in a speed flying accident (speed flying is a high-performance version of paragliding) more than a decade ago, lives in one of these affordable housing units. It didn’t come easy: The Community Housing Trust, one of the three entities developing affordable housing in Jackson, accepts applicants who earn less than 120 percent of the area’s median income, awarding them points based on how long they have lived in town, whether they do essential work in the town, and how much community service they have put in over the years. Stone runs a foundation, Teton Adapted, that works to make the great outdoors more accessible to people with disabilities, as well as a trails consulting business, earning him about $70,000 a year. That puts him well below what he would need to afford a market-rate home in Jackson. During the pandemic, Stone and his partner, Caitlin, a physical therapist, qualified—by virtue of their income and the value of their work to the community—to purchase a disability-accessible unit, and along with their pit-bull mix George, they moved in in 2021. It was a godsend. Able to access a Fannie Mae–backed 30-year mortgage at 2.5 percent interest, they pay $1,700 a month for their mortgage and HOA dues, a fraction of what they would have to spend on the open market.

“This place raised the quality of my life, took it to a whole other level,” Stone says, sitting in his wheelchair in the common area of the airy modern apartment complex. “Now where I live is locked in. I don’t have to worry about that anymore.”

For thousands of other locals, however, the angst continues. The Community Housing Trust recently found that for a family to be able to afford a home in town selling at the average market price, they would have to bring in upwards of $600,000 per year. They would also, notes the CHT’s executive director, Anne Creswell, have to come up with many hundreds of thousands of dollars for a down payment.

But the life-affirming stories of Joe Stone and other locals gives Creswell hope. The individuals and families her organization has managed to house in the 185 units that it has built in Jackson over the past 32 years are validations of all the hard work that she and her colleagues have put in. And it’s true that in Jackson, Bozeman, and many other Western cities that have been transformed by the influx of high-end remote workers, you’ll find some of the country’s most creative affordable housing trusts, be they local chapters of Habitat for Humanity or organizations such as the CHT.

You’ll also find people who have devoted years of their lives to working on tenants’ rights in an increasingly hostile environment. They have chalked up a number of successes: Bozeman banned most short-term rentals recently, part of a larger national trend to rein in Airbnb, and a tenants’ union that Joey Morrison, Bozeman’s 29-year-old deputy mayor, helped establish has been pushing for the right of all tenants to have legal representation during eviction proceedings.

Yet as conversations with advocates and officials across the region make painfully clear, they are engaged in a Sisyphean struggle. For every Joe Stone or Tracy Mulligan, there are many others who simply have no options for affordable housing.

In Jackson, the locals have begun to worry about the fact that firefighters and police officers can’t afford to live close by, which means a shortage of hands in an emergency. Similarly, many of the hospital’s staff live out of town, which creates huge healthcare risks during winter storms when the passes into Jackson close and employees can’t reach the hospital. Rumor has it that things got so dire last winter, with roads being inaccessible and employees unable to drive to work, that the hospital considered chartering helicopters to attempt to fly in vital staff.

“Dude,” Josue Moreno says as he finishes his beer outside the Virginian and contemplates the messy reality that the Covid-era housing market has created in the town he loves. “Jackson is the best of everything and the worst of everything.” He pauses. “There is no in-between.”

Support independent journalism that exposes oligarchs and profiteers

Donald Trump’s cruel and chaotic second term is just getting started. In his first month back in office, Trump and his lackey Elon Musk (or is it the other way around?) have proven that nothing is safe from sacrifice at the altar of unchecked power and riches.

Only robust independent journalism can cut through the noise and offer clear-eyed reporting and analysis based on principle and conscience. That’s what The Nation has done for 160 years and that’s what we’re doing now.

Our independent journalism doesn’t allow injustice to go unnoticed or unchallenged—nor will we abandon hope for a better world. Our writers, editors, and fact-checkers are working relentlessly to keep you informed and empowered when so much of the media fails to do so out of credulity, fear, or fealty.

The Nation has seen unprecedented times before. We draw strength and guidance from our history of principled progressive journalism in times of crisis, and we are committed to continuing this legacy today.

We’re aiming to raise $25,000 during our Spring Fundraising Campaign to ensure that we have the resources to expose the oligarchs and profiteers attempting to loot our republic. Stand for bold independent journalism and donate to support The Nation today.

Onward,

Katrina vanden Heuvel

Editorial Director and Publisher, The Nation

More from The Nation

“I’m Terrified”: Trans-Feminine Athletes in Their Own Words “I’m Terrified”: Trans-Feminine Athletes in Their Own Words

In part two of a series, trans women athletes describe what it’s like to compete in the Trump era.

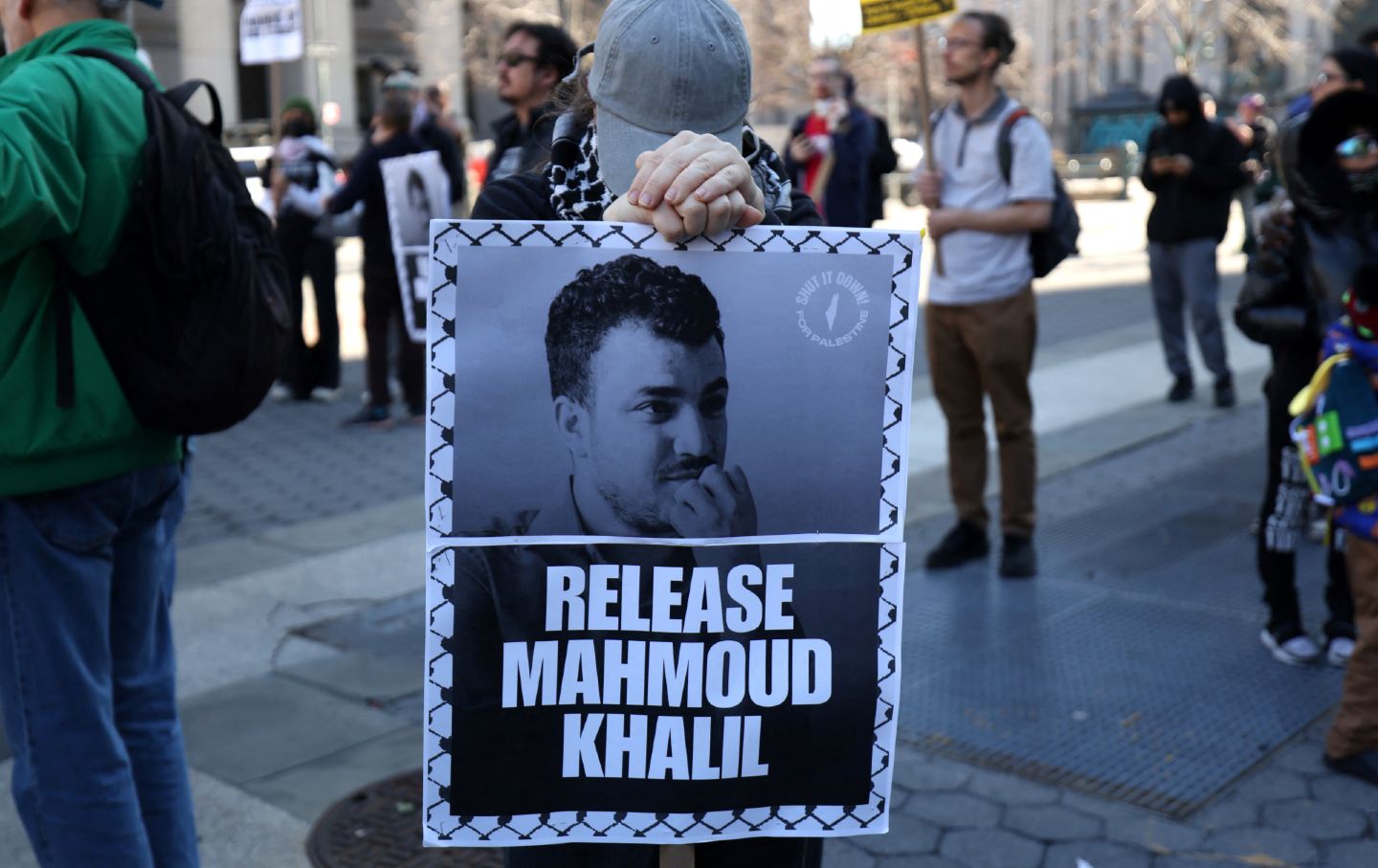

Columbia Is Betraying Its Students. We Must Change Course. Columbia Is Betraying Its Students. We Must Change Course.

The administration is choosing complicity over courage in the case of Mahmoud Khalil. It’s time for the faculty to demand a new path.

The Trans Cult Who Believes AI Will Either Save Us—or Kill Us All The Trans Cult Who Believes AI Will Either Save Us—or Kill Us All

What the Zizians, a trans vegan cult allegedly behind multiple murders, can teach us about radicalization and our tech-addled politics.

We Are Asking the Wrong Questions About Mahmoud Khalil’s Arrest We Are Asking the Wrong Questions About Mahmoud Khalil’s Arrest

The only relevant question is not “How can the government do this?” It is “How can we who oppose this fascist regime stop it?”

DOGE’s Private-Equity Playbook DOGE’s Private-Equity Playbook

Elon Musk's rampage through the government is a classic PE takeover, replete with bogus numbers and sociopathic executives.

Parts of LA Are Not Going to Be Habitable Parts of LA Are Not Going to Be Habitable

Insurers have figured out that risk is too high in parts of California. We need to re-conceive how people are housed, and fast.