As Homelessness Spikes in New York City, Eric Adams Is Trying to Close a Homeless Shelter

The possibility of closure looms over the patrons of the Mainchance drop-in center.

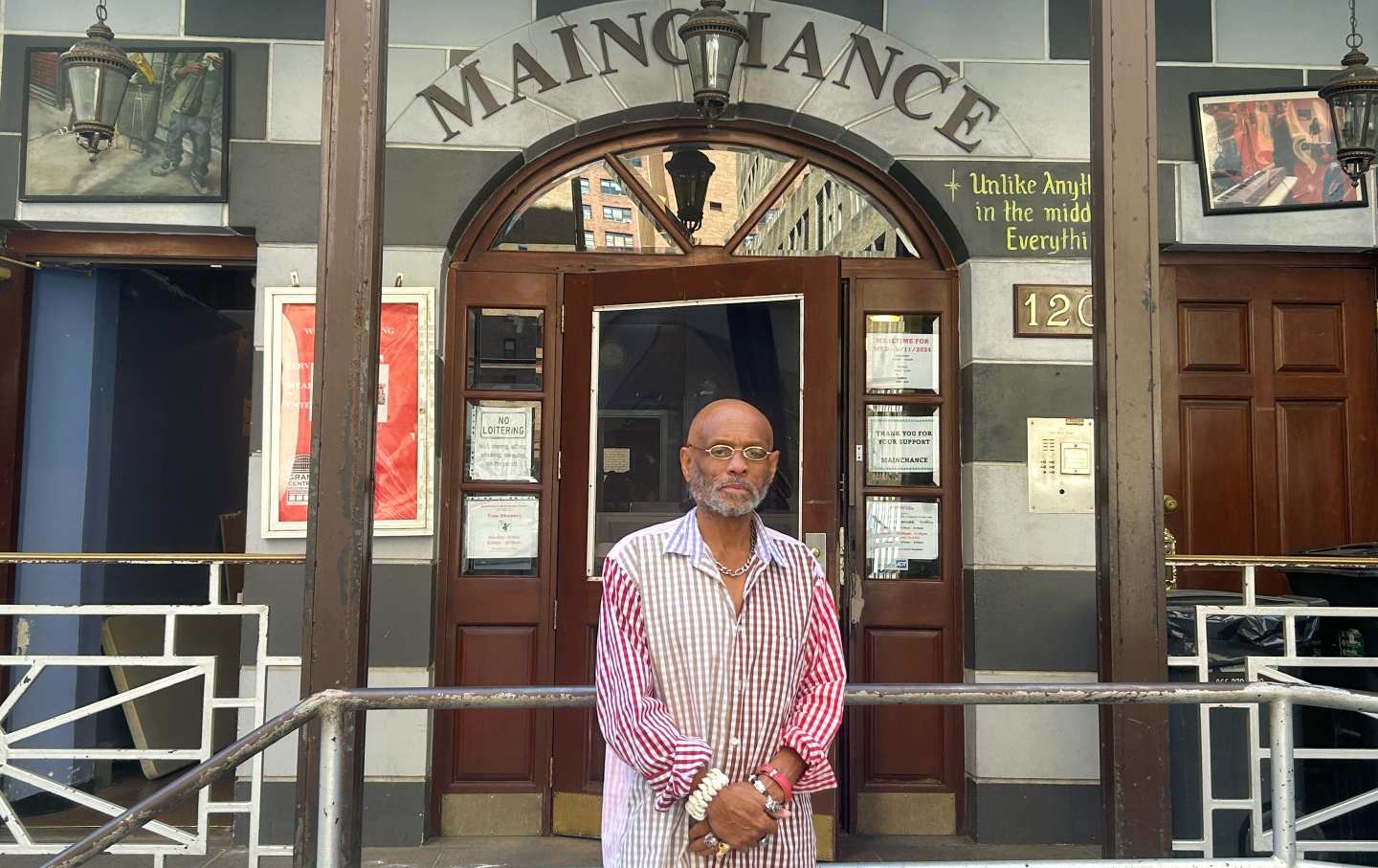

Brady Crain, the executive director of Mainchance, stands outside the drop-in center in midtown Manhattan.

(Xenia Gonikberg)

New York City—Squeezed between a five-star hotel and a Korean cultural center in midtown Manhattan lies the Mainchance drop-in center, a four-story building with a black-and-white tile exterior and a bright orange awning with the phrase “COMMUNITY FOR ALL” printed in block letters.

To passersby, “Community for All” may seem like only a catchy phrase, but it’s a mantra at Mainchance, which has been operating as part of the nonprofit network Grand Central Neighborhood Social Service Corporation (GCNSSC) since 1989.

Brady Crain, Mainchance’s executive director, told me that calling it a “drop-in” is a bit of a misnomer: “Nobody is dropping in and out.” Many of Mainchance’s patrons are “regulars” who frequent the shelter for its day-to-day services and monthly food pantry.

Crain estimated that the center serves meals to more than 300 people a day. Along with hosting the monthly food pantry, Mainchance provides showers, bus vouchers, banking services, and medical care and referrals. It also helps connect clients to detox centers and churches with available beds. The center itself doesn’t have beds, though on the second floor, there is a “resource room” where people can rest.

But New York City under Mayor Eric Adams wants to cancel the Department of Homeless Services’ contract with Mainchance, shuttering the center. On page 25 of Adams’s 2025 fiscal budget draft, the city labels Mainchance “underperforming” and says that closing it would save around $3.7 million over the next two years.

But on June 28, just two days before the city informed Mainchance that it wanted the center closed, the Department of Homeless Services rated Mainchance “very good” based on a site inspection.

“The city keeps giving us all these mixed messages,” William Kornblum, the chairman of GCNSSC’s board of directors, told me. “On one hand, they’re praising us and offering us a new contract for additional work, while on the other hand, they’re telling us we have to close.”

(The mayor’s office and the Department of Homeless Services did not respond to requests for comment.)

As homelessness in the city continues to rise, the work of Mainchance is increasingly important. In 2022, more than 14 percent of New Yorkers experienced food insecurity, nearly double the national average. About 146,000 people access shelters every month, according to City Limits. The number of homeless people in New York City is at its highest level since the Great Depression, and the number of homeless single adults is more than double what it was just a decade ago. The main reason for the spike in homelessness is the lack of affordable housing, with the city losing more than 1 million affordable housing units between 1996 and 2017.

Despite increasing need, drop-in centers like Mainchance remain few and far between. There are currently just six such sites across New York City, with two in Manhattan.

Crain, who has been working at Mainchance since its move to 32nd Street in 2005, said the organization is willing to turn the shelter into a “safe-haven site”—meaning it would provide semi-private or private rooms with beds—if that means keep the doors open. The city, according to Crain, is prioritizing placing people in beds, not providing other services.

In February 2024, Mainchance submitted a Request for Proposal that would transform Mainchance into an overnight shelter. And the city rejected the idea. The Department of Homeless Services told Mainchance that turning the shelter into a safe haven “would likely be a few years out.” But Mainchance’s lawyer, Marc Gross, said the city is assuming that the process of converting Mainchance into an overnight shelter would take years, although a contractor estimated that it would really just take up to 90 days. The conversion to a safe-haven shelter is “very straightforward,” Gross explained: All Mainchance needs to do is put beds where there are currently chairs, install sprinkler systems in the sleeping area, and build another shower and more exits.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →Gross has been fighting with the Department of Homeless Services to prevent the shelter’s contract from ending. Mainchance filed a restraining order against the city in June to delay the city from closing it. Gross, a litigation lawyer and senior counsel for Pomerantz LLP, is on the board of Mainchance and is taking the case pro bono.

After filing a preliminary injunction against the Department of Homeless Services, there was a hearing on July 23 to present arguments in front of a judge. Gross told me the contract between the Department of Homeless Services and Mainchance cannot be terminated without a valid reason. Mainchance is now waiting for Judge Lynn Kotler’s ruling. If she accepts the validity of Mainchance’s argument, then the case will head to trial. That decision is expected to come in September.

The fight to keep Mainchance open is about helping the poor and homeless in the community, Kornblum told me. “The immediacy of the care that we can offer and the location in the human ecology of central Midtown Manhattan is critical,” he said. “If you lose that, you lose something very important for the populations that we serve.”

During the monthly food pantries, people often stand in line for hours to collect the fruit, the freshly cooked meat, and canned fish and vegetables waiting for them inside. Though the August pantry was scheduled to start at 2 pm, the “lunch rush” began at 1 with the first few people taking their place across the street, waiting for Crain and other Mainchance staffers to usher them inside. Once inside, customers are asked to sign in and take a number, which they will then wait to hear announced before making their way down to the rows of tables lined with food. Staffers help the customers pick out groceries and pack them into their carts, where they are then helped to the exit.

Dorothy Simon, an 80-year-old who lives a few blocks from Mainchance, was among the first people waiting for the doors to open. She’s used a wheelchair for the past seven years after suffering a spinal-cord injury at a construction site. It isn’t easy for her to get around the neighborhood even on the sidewalks, she said, and so having a reliable place to go for groceries is essential.

If the shelter were to close, she told me, “I won’t be able to get certain food because I’m not going to be able to afford to buy some of the stuff that you can get here.”

The pantry doesn’t just help the individuals who pick up the food. “This place gives me more than any other place,” Gary, one of the food drive’s most frequent patrons said. “You get meat, you get protein here. I get salmon in a can.” Gary, who asked that his last name not be used, is a 74-year-old Vietnam War veteran and former nurse’s aide who uses the food pantry as an opportunity to collect food for his neighbors as well as himself.

“On SNAP I only get $4 a month. My Social Security is only $840 a month. And on my floor, I got five bed-bound guys I help out. And I get their food for them. Without it, they starve,” he said.

Kristen Hodge, 44, said she was worried about losing the community she’s built at Mainchance. Hodge said her 3-year-old daughter, Liberty, especially enjoys the fresh fruit and interacting with everyone.

“They were more welcoming than other places,” Hodge said. “Here you get good conversation, good company, the people are nice. They actually get to know you.”

For the patrons and staff at Mainchance, the possibility of closure weighs on them. Crain noted that they are trying to take things one day at a time, but for now, Mainchance remains in limbo until the judge’s decision. And if the shelter were to close, he said the city would lose more than just a physical space for the city’s homeless: “We do stuff that can’t be measured. We create relationships. We connect with our customers.”