Can Mandated Nurse-to-Patient Ratios Fix Hospitals’ Staffing Crisis?

The nurse staffing crisis isn’t new, but the situation has only intensified since the Covid-19 pandemic. “Our hospitals are at risk if they don’t have enough nurses.”

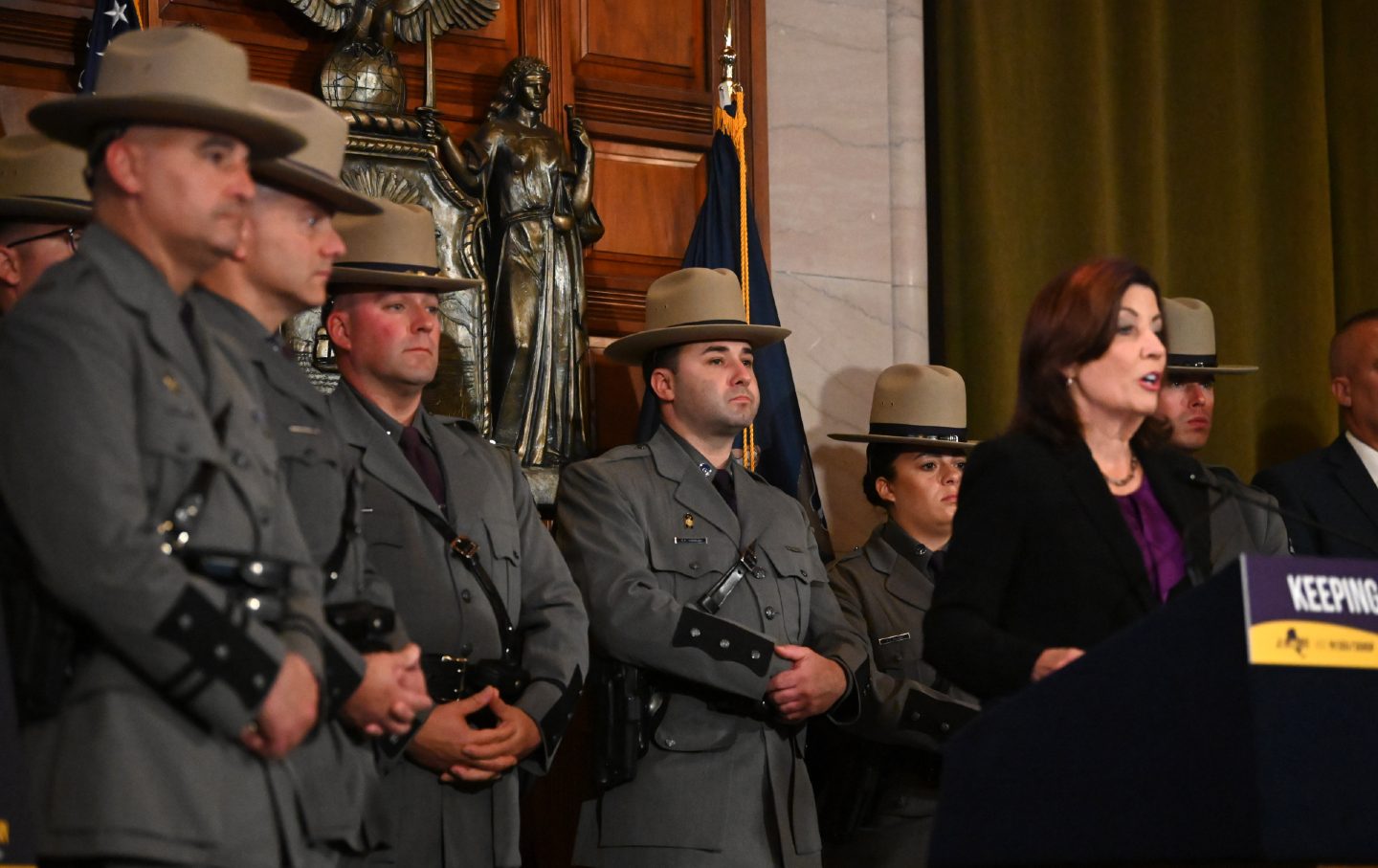

Nurses from Montefiore Medical Center march during their strike in front of the medical center in the Bronx, New York City, in January 2023.

(Fatih Aktas / Getty)A woman with dementia arrived at Montefiore Medical Center’s intensive care unit in near-psychosis. Frantic and extremely cold, she was swarmed by doctors and nurses. They drew blood. They ran tests. They delivered emergency medication. When her vital signs and tests confirmed that her condition was stable, they rushed off to the next emergency.

Her nurse, Benny Mathew, was the last to leave. He recalled the woman grabbing onto his hand and saying, “I feel like I’m gonna die now. Can you stay with me?’” But Mathew had at least five other patients at the time, two of whom were still waiting for a bed and urgent medical attention. They needed him more. So he rechecked her vitals. He calmed her. Then he left. Several hours later, the woman died. She had no family or friends present.

“It was a really horrible feeling,” said Mathew, who is vice president of National Nurses United’s executive council. “We cannot provide the care because of inadequate staffing, and that deeply hurts in our psyche.” He wished he could have at least provided her comfort and “the human touch” in her final hours. In hospitals with chronic understaffing, many nurses burn out. They quit. They mourn the care they could have provided, and carry that grief home with them.

Nurse staffing crises are nothing new. But since the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic, the situation has intensified. In response, a growing number of states are considering a controversial policy solution: minimum nurse-to-patient staffing ratios.

In 1999, California became the first state to mandate such ratios, which cap the number of patients assigned to each nurse. Union nurses championed the bill as a win for patient safety and health outcomes. Hospital associations blasted it as ineffective and costly. Decades later, this debate has spread to state legislatures across the nation. In August, Oregon joined California in enacting mandatory nurse staffing ratios statewide. In July, Pennsylvania’s state House passed the Patient Safety Act, which would enact minimum nurse staffing, pending state Senate approval. In June, Connecticut adopted a law strengthening the power of hospital staffing committees to enforce proper ratios. Nursing unions in Washington, Montana, and Ohio too made unprecedented headway toward legislation this year.

The pandemic was a “wake-up call to everyone,” said Linda Aiken, founding director of the Center for Health Outcomes and Policy Research at the University of Pennsylvania School of Nursing. “Our hospitals are at risk if they don’t have enough nurses. It was the first time in my career that I have seen people in the hospital world think all of a sudden, ‘We’re really in trouble.’”

In January, Mathew and more than 7,000 nurses at Montefiore and Mount Sinai Hospital in New York City went on strike for three days for better staffing. They were objecting to the chronic “unsafe staffing” that had become normalized over the pandemic, said Matt Allen, a Mount Sinai nurse and vice president of New York State Nurses Association’s executive committee. Early in the pandemic, turnover was high, with over 100,000 nurses across the nation leaving the workforce due to stress, burnout, and retirement.

The ones who stayed saw their patient loads multiply.

When hospitals found that they could push these remaining nurses to handle huge influxes of patients during an emergency, they decided to maintain this understaffing, Allen explained. After all, fewer nurses cost less money. “Big hospital corporations like mine,” Allen said, “they’re only focused on the bottom line.” Mount Sinai had more than 800 nursing vacancies that piled up and went unfilled before the strike, he added. Mount Sinai declined to provide comment.

To address this understaffing, the Montefiore and Mount Sinai nurses demanded that enforceable staffing ratios be written into their contracts. By the strike’s three-day mark, the hospitals yielded. Mathew’s department, for example, must now staff at least one nurse for every two critical-care patients—a rule the New York State Department of Health recently enacted independently in intensive care units and other settings statewide. But if Montefiore or Mount Sinai fails to staff units appropriately, nurses can bring a case to an arbitrator who can issue financial penalties.

This pressure already appears to be working: Allen said Mount Sinai recently slashed its nursing vacancies down to around 400. At Montefiore, Mathew said new nurses are coming in for orientation every week. From their perspectives, the ratios both pressured hospitals to hire more nurses and made the work environment safer.

But the Greater New York Hospital Association, which represents Montefiore and Mount Sinai, was not as happy with this solution. “We believe government-mandated staffing ratios would undermine real-time patient care decisions, rob health care facilities of the flexibility to meet crises and respond to emergencies, and crowd out other members of the health care team,” a statement provided by a spokesperson read.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →From state to state, this is the same debate. Hospital and nursing associations agree that there is a staffing crisis, but they disagree on ratios being the solution. The Connecticut Hospital Association, for instance, argued that the state should instead help fund cash recruitment and retention bonuses, student loan payment assistance, and tuition assistance for nurses. They said their own hospitals are providing financial incentives, supporting continuing education, and partnering with colleges and technical schools.

But to John Brady, a registered nurse and a vice president of the statewide labor federation AFT Connecticut, the only way to retain and recruit nurses is to improve the work environment. That means guaranteeing a manageable, safe patient load. “If we don’t have decent ratios, you’re gonna keep losing people,” Brady said. “You can keep trying to fill the bucket with people by opening seats in universities for nursing and stuff, but the bucket’s leaking out on the bottom. You can’t fill it fast enough.”

While Mount Sinai and Montefiore put their own ratios to the test, nursing unions remain confident that holding hospitals to a staffing standard could solve the staffing crisis. For inspiration, they look toward California: a test case of two decades.

When California’s nurse staffing mandate was first implemented in 2004, there was an acute shortage of nurses in California’s hospitals, said Aiken, who researches nurse staffing legislation. But after new minimum staffing levels were imposed, nurses came back to hospitals.

Some nurses decided to take on extra hours. Some migrated to California from other states. Others even returned from retirement, according to Sandy Reding, RN, president of the California Nurses Association.

As it turned out, there were enough nurses to fix the crisis.

Nursing unions strongly oppose hospital associations’ calling the current staffing crisis a “staffing shortage,” because it implies a lack of nurses available to work. In reality, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics and the National Council of State Boards of Nursing, there are more than 1 million registered nurses nationwide who have active licenses but are not employed as nurses. “It’s not a lack of RNs,” said Janice Stauffer, president of the Danbury Nurses Union in Connecticut. “There’s a lack of RNs that are willing to work in poor working conditions.”

Sherri Dayton, president of the Backus Federation of Nurses in Connecticut, said unsafe staffing practices force nurses to risk both their licenses and their patients’ lives. That drives nurses to quit en masse.

When Dayton started working as an emergency room nurse at Backus Hospital in 2012, she was usually responsible for four patients at a time. Since the pandemic, she has been assigned up to 11 patients at once. With each patient interaction taking at least 10 minutes, hourly rounding is physically impossible, said Dayton, who is also president of her hospital’s nursing union. She feels that understaffing threatens her ability to care for patients safely. Dayton referenced a 2002 study by Aiken that found that increasing a nurses’ workload by one patient increased the likelihood of a patient’s dying by 7 percent.

Meanwhile, patients in California hospitals receive an average of three more hours of nursing care compared to other states, Aiken said. “It’s common sense that if you have fewer patients, you’re going to have better outcomes and you’re going to be able to reach your patients faster,” said Reding. To her, a ratio means ensuring that medication is administered in time. It means catching a hike in blood pressure early, before a stroke happens.

When asked for comment, the California Hospital Association declined and referred me to Joanne Spetz, director of the Philip R. Lee Institute for Health Policy Studies at University of California, San Francisco.

Spetz, an expert on nurse staffing legislation, said that California’s ratios improved nurses’ job satisfaction, rates of burnout, and perception that they had adequate time with their patients. However, she emphasized the cost of implementing these ratios. The upfront cost of hiring more nurses can be high. There is evidence that some hospitals initially laid off some support staff and reduced charity care to free up money for more nurses, she said.

Hospital associations often argue that they would have to turn to expensive temporary, contract labor, simply to meet ratios. In testimony submitted by James Iacobellis of the Connecticut Hospital Association, he noted that staffing crises early into the pandemic drove up demand for travel nurses, with a price tag of $519 million.

Spetz said the public should decide if ratios are worth the money. “The evidence is not clear that ratios are good or bad,” Spetz said. “You can’t regulate that a hospital be a good place to work.”

However, Reding argued that hospitals would save money in the long-term by implementing ratios. By fostering a safer work environment, ratios would, in theory, reduce turnover. That means less money spent training new nurses. In 2022, the national turnover rate for staff nurses was 22.5 percent, with the average cost of each staff turnover being around $40,000.

Aiken emphasized that the United States spends $1 trillion on hospital care every year. She questioned why there would not be enough money to pay nurses, who play the most labor-intensive role in care. To her, hospitals should already be investing in proper staffing, regardless of a mandate. “They’ve had 20 years to start making the investment, and they never have done it yet,” Aiken said. “Without some creation of standards that have some teeth in them, most of them are not going to do it.” In California, around half of hospitals already met the staffing ratio before the mandate. For the other half, the mandate forced them to increase their staffing.

John Welton, professor emeritus at University of Colorado College of Nursing, agreed that understaffing is a threat to safe and effective care. But he disagreed that ratios are the solution. To him, minimum staffing ratios are inflexible and fail to account for variation in patients’ needs. “We want the right amount of nursing care, not the minimally safe amount of nursing care,” he said. As a nurse of more than 40 years, Welton said he has never met an “average patient”—some patients may need less care and some more. The Connecticut Hospital Association likewise called ratios “rigid,” and inferior to “the professional judgment of nurses and care providers.” They argued that ratios prevent a flexible response during emergencies, and may increase waiting times for patients.

However, Aiken emphasized that the minimum standard is not necessarily the “ideal standard,” “It’s trying to set a floor and to say nobody can go below this floor because it’s unsafe.” She compared it to having a fire plan in an emergency. Many hospitals may even staff better than this standard, as was the case in California before the mandate. Oregon’s own new staffing law will factor in patient acuity, giving nurses some ability to limit their number of patients beyond the ratio, said Erica Swartz, an Oregon Nurses Association nurse. Plus, hospitals may deviate from the ratio if they pursue an innovative care model that includes other clinical staff—as long as it is approved.

“I feel hopeful that the bill can raise the standards of care that we have for patients in Oregon,” Swartz said, “And help slow the exodus of nurses we have from the profession.”

To Aiken, the progress in Oregon signals that more states could be successful in passing legislation. She pointed to Pennsylvania’s Patient Safety Act, which would establish mandatory ratios. The bill had passed with strong bipartisan support in the House and was now awaiting action by the Republican-controlled Senate. In a move unheard of among hospital executives, the CEO of Penn Medicine even coauthored an op-ed with Aiken endorsing the bill.

Other states with actively pending bills include Massachusetts, Maine, Michigan, and Illinois, she added. Meanwhile, some nurses aren’t waiting for their states to see the light and are pushing staffing requirements at the hospital level.

At Robert Wood Johnson University Hospital in New Jersey, 1,700 nurses have been on strike since early August. Judy Danella, a staff nurse and president of her union, United Steelworkers Local 4-200, said they gleaned inspiration from California and New York City. “We looked at other hospitals around,” Danella said. “We are just asking for the same kind of staffing.”

Allen expressed pride in being able to set precedent for nurses through their strike, and stand up for both “their profession and their patients.” He said the ratios have not yet solved the crisis, but they are tools they can use to advocate for safer staffing. “We hold a license that says we have to take care of our patients, but sometimes the hospitals don’t allow us to do that.” Allen said. “So we have to take things into our own hands.”

Hold the powerful to account by supporting The Nation

The chaos and cruelty of the Trump administration reaches new lows each week.

Trump’s catastrophic “Liberation Day” has wreaked havoc on the world economy and set up yet another constitutional crisis at home. Plainclothes officers continue to abduct university students off the streets. So-called “enemy aliens” are flown abroad to a mega prison against the orders of the courts. And Signalgate promises to be the first of many incompetence scandals that expose the brutal violence at the core of the American empire.

At a time when elite universities, powerful law firms, and influential media outlets are capitulating to Trump’s intimidation, The Nation is more determined than ever before to hold the powerful to account.

In just the last month, we’ve published reporting on how Trump outsources his mass deportation agenda to other countries, exposed the administration’s appeal to obscure laws to carry out its repressive agenda, and amplified the voices of brave student activists targeted by universities.

We also continue to tell the stories of those who fight back against Trump and Musk, whether on the streets in growing protest movements, in town halls across the country, or in critical state elections—like Wisconsin’s recent state Supreme Court race—that provide a model for resisting Trumpism and prove that Musk can’t buy our democracy.

This is the journalism that matters in 2025. But we can’t do this without you. As a reader-supported publication, we rely on the support of generous donors. Please, help make our essential independent journalism possible with a donation today.

In solidarity,

The Editors

The Nation