EDITOR’S NOTE: In the fall of 2021, a group of students at Wake Forest University took part in a class on data-driven advocacy. Their objective was to find a question that was broadly relevant to inequality, answer that question using basic tools of data science, and convincingly communicate that answer clearly to a broad audience in a partnership with the Puffin Nation Fund Writing Fellowships. This article is the third of the final products that came out of that course. The authors sought to understand how the academic achievement, mental health, and future income of children of incarcerated parents compare to those with deceased parents.

If a parent dies, the burden created on their children is substantial. A bereaved child loses access to their deceased parent’s financial, emotional, and social support. This is also true if a parent is incarcerated, but it can come with additional emotional and social burdens that are less obvious.

When a child loses a parent to incarceration, they spend significant days like Mother’s Day and Father’s Day mourning the absence of an individual who is still alive or navigating the barrier that keeps them apart. The household may need to pay for communication with the jailed parent and support them during and after their sentence, while simultaneously maintaining a single parent household. Due to the shameful implications surrounding incarceration, these children may be socially stigmatized because of their incarcerated parent. Eric Martin uses the term “hidden victims” to describe the family members harmed by their relative’s incarceration, and argues that these family members receive insufficient emotional support and lack support systems and safety nets.

Parental loss, whether in the form of incarceration or death, can harm children as they progress into adulthood. How does the academic achievement, mental health, and future income of children of incarcerated parents compare to those with deceased parents? We find that they are surprisingly comparable, and in some cases the bereaved actually fared better.

Our conclusion is based on data from the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth (NLSY), a study that has tracked over 8,000 adolescent Americans since 1997. If our conclusion is true, its social and economic impact could be enormous: there were 2.3 million people incarcerated in the United States in 2020 (about 1.3 million in state and federal prisons, the rest in local confinement or elsewhere), and “50 percent to 75 percent of incarcerated individuals report[ed] having a minor child. It may help us understand the scope of this problem—and the importance of solving it—if we think about the children of prisoners the same way that we think about bereaved youngsters.

The detrimental effects that parental incarceration and death have on children have been extensively researched in the past, although usually they are not compared. Existing studies of incarcerated parents attempt to explain the immediate and long-term consequences for their children and to understand the unique hardships that those children endure as a result. Based on these studies, we expect the children of absent parents to possibly suffer reduced educational achievement, a greater risk of mental health issues, and economic harms lasting beyond childhood.

The NLSY allows us to compare the effect of parental imprisonment to parental death on the respondents’ educational, behavioral, and economic life outcomes in a representative sample of Americans. We used this data to create a parental status variable with three categories: (1) at least one parent is incarcerated and not deceased, (2) at least one parent is deceased and not incarcerated, and neither parent is incarcerated nor deceased. When studying the respondents’ economic outcomes, we examine the effect of parental status separately for three racial/ethnic categories coded by the NLSY: (1) Black, (2) Hispanic, and (3) Non-Black and Non-Hispanic (which is primarily composed of whites and Asians).

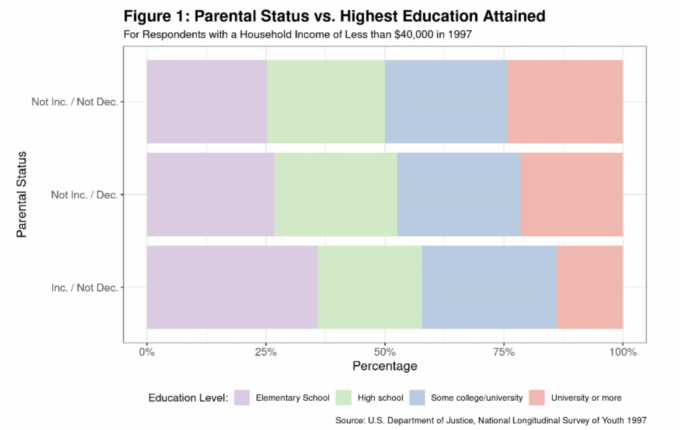

Figure 1 shows the education level of respondents to the NLSY’s 2019 survey, displaying the outcomes of 2,310 respondents whose family had an income of less than $40,000 a year at the start of the survey in 1997. Limiting the sample in this way addresses the possibility that children from poorer families endure both reduced education and a greater likelihood of parental loss because of poverty.

Children with an incarcerated parent have, in the aggregate, the lowest levels of education. The most common education level for respondents from a low-income family who had an incarcerated parent was elementary school. Respondents with incarcerated parents also exhibit the lowest rate of university completion—just under 60 percent as many respondents with an incarcerated parent completed a university education compared to the baseline (respondents with neither an incarcerated nor deceased parent). Educational attainment among respondents with a deceased parent was comparable to the baseline.

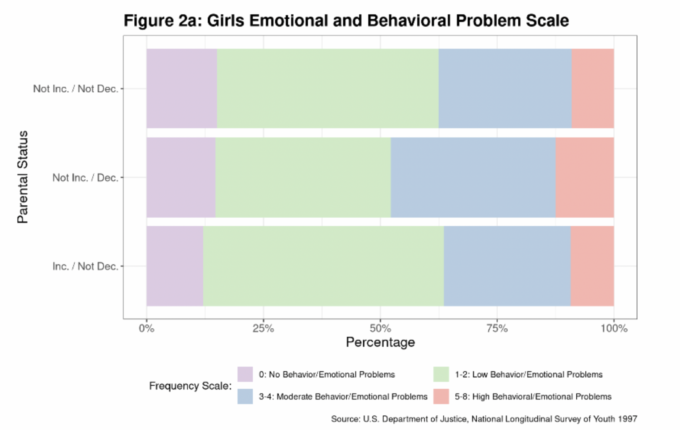

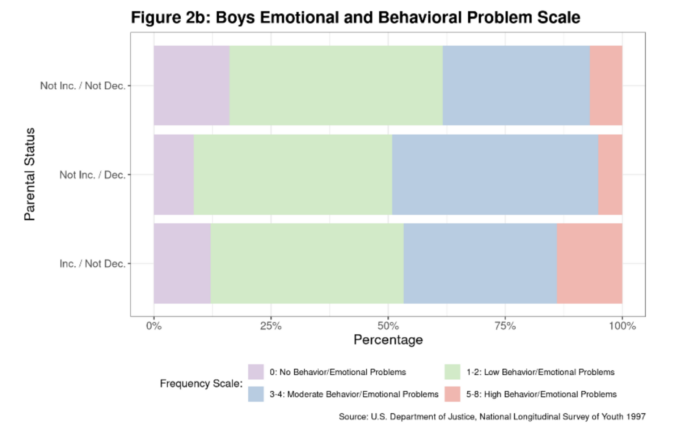

The second (Figure 2a) and third (Figure 2b) visualizations compare parental status to a measure of childhood mental health for 1,911 girls and 1,931 boys, respectively, for whom data was available. This measure tracks self-reported behavioral and emotional problems in childhood as recorded during the first NLSY survey in 1997. Girls with a deceased parent were more likely than others to report frequent or persistent behavioral problems, but differences among the three parental status groups are below the threshold of statistical significance. By contrast, boys with incarcerated or deceased parents were both more likely to report problems, with the sons of incarcerated parents facing the highest rate of the most severe problems. The relationship between parent status and emotional problems is statistically significant among boys.

The second (Figure 2a) and third (Figure 2b) visualizations compare parental status to a measure of childhood mental health for 1,911 girls and 1,931 boys, respectively, for whom data was available. This measure tracks self-reported behavioral and emotional problems in childhood as recorded during the first NLSY survey in 1997. Girls with a deceased parent were more likely than others to report frequent or persistent behavioral problems, but differences among the three parental status groups are below the threshold of statistical significance. By contrast, boys with incarcerated or deceased parents were both more likely to report problems, with the sons of incarcerated parents facing the highest rate of the most severe problems. The relationship between parent status and emotional problems is statistically significant among boys.

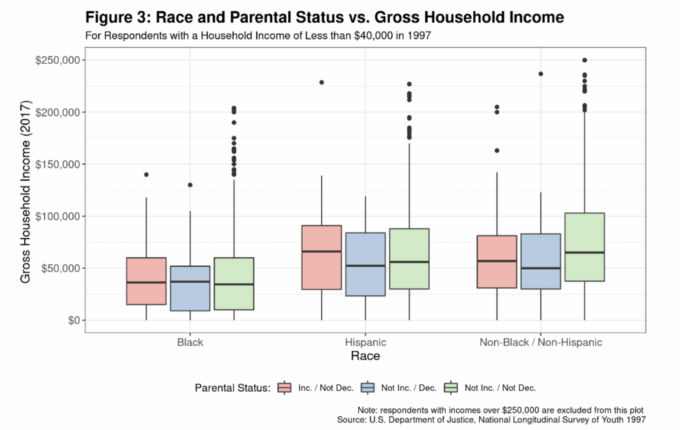

The last visualization (Figure 3) presents a box plot analysis of the 2017 gross household income of respondents whose families earned less than $40,000 in 1997. By observing only this subgroup of respondents, we can compare the life outcomes of individuals with incarcerated or deceased parents to the baseline while holding all respondents’ economic starting point relatively constant. (We also expect any detrimental effects of parental incarceration or death to be worse for low-income families.)

The last visualization (Figure 3) presents a box plot analysis of the 2017 gross household income of respondents whose families earned less than $40,000 in 1997. By observing only this subgroup of respondents, we can compare the life outcomes of individuals with incarcerated or deceased parents to the baseline while holding all respondents’ economic starting point relatively constant. (We also expect any detrimental effects of parental incarceration or death to be worse for low-income families.)

Our analysis reveals that respondents whose parents were either incarcerated or deceased during their childhood were, on average, less prosperous in 2017. But although Black and Hispanic respondents have lower average income compared to non-Black non-Hispanic respondents, the effect of incarceration or death of a parent is not stronger in these groups; in fact, it might be weaker. We do not know why this is the case, but perhaps the already reduced income of respondents in racial and ethnic minority groups limits how much further they can fall due to the loss of a parent.

Based on our findings, the children of an incarcerated parent suffer disadvantages that are as bad or worse than those with a parent who has died. On average, they attain lower levels of education. Boys with incarcerated parents are more likely to report a high frequency of emotional and behavioral problems. And the children of incarcerated parents earn lower incomes in adulthood.

We cannot say definitively which form of parental absence is more harmful to the well-being of children as they develop into adulthood. Future research may be able to compare these groups on different outcomes or with more complicated designs that improve on our conclusion. But this is hardly the point; even if the consequences are similar, parental incarceration in the United States is not only a heavy burden for children to bear but a social problem of immense proportions. We hope that this future research and our own findings will prompt policy measures to help the “hidden victims” of incarceration live happier and more prosperous lives.