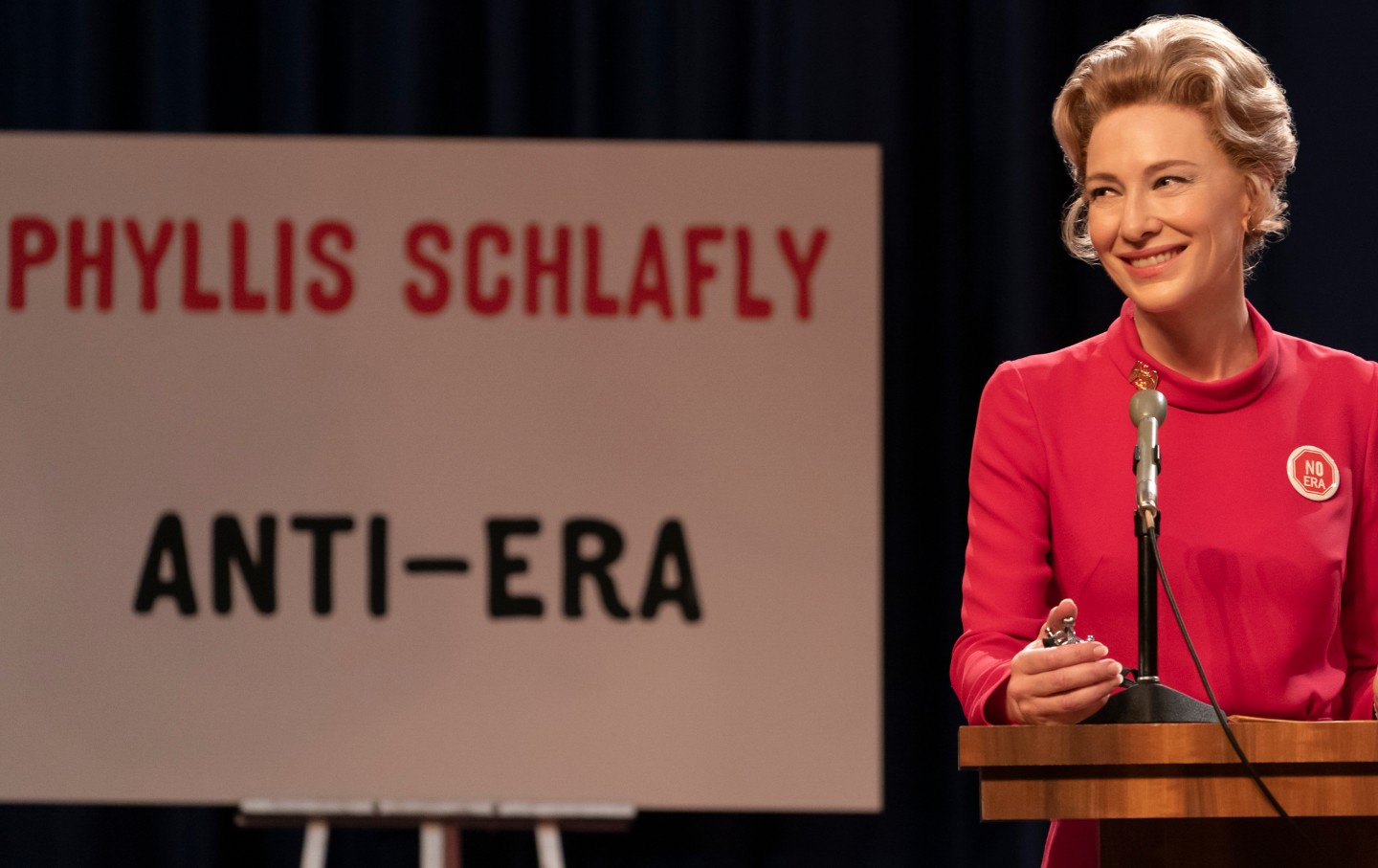

Cate Blanchett as Phyllis Schlafly in the fourth episode of Mrs. America.(FX Networks)

“She’s a liar, a fearmonger and a con artist,” Bella Abzug says of Phyllis Schlafly about two-thirds of the way into Mrs. America, FX’s fascinating nine-part miniseries about Schlafly and the struggle over the Equal Rights Amendment. “But worst of all, she’s a goddamn feminist. She might be one of the most liberated women in America.” Indeed. Schlafly, a devout Catholic wife and a mother of six, was a tireless, extremely well-connected right-wing ideologue who made a fabulous career out of telling women that their place was in the home. Unfortunately, she was very good at her job. From a newsletter and meetings held in her living room in Alton, Illinois, she forged the contemporary anti-feminist movement, which not only scuttled the ERA, which fell three states short of ratification in 1982, but also realigned both major political parties around support or hostility to women’s rights. To a frightening extent, we are living in the world Schlafly made.

Some of my feminist friends think Mrs. America is too sympathetic to Schlafly. I think that impression is largely due to Cate Blanchett’s brilliant performance. She is so beautiful, you want to look at her forever, with a creamy softness lacking in photos of the real-life Schlafly, and she brings a humorous twinkle to Schlafly’s steely self-control as well. Blanchett’s Schlafly is a bit like Becky Sharp in Vanity Fair; it’s fun to watch her scheme her way to the top. There’s something innately appealing, too, about her drive and pluck. I found myself almost siding with her. Don’t let those Republican men put you down, Phyllis! Good for you, going to law school at 50! And if feminists dismiss you as a kook, just show them how wrong they are.

Never underestimate your enemies is one of the main political morals here. The feminist main characters—Gloria Steinem (Rose Byrne), Betty Friedan (Tracey Ullman), Brenda Feigen-Fasteau (Ari Graynor), Bella Abzug (Margo Martindale), Jill Ruckelshaus (Elizabeth Banks), and Shirley Chisholm (Uzo Aduba)—each get an episode, and it is painful to watch their exuberant confidence slowly fade as they belatedly realize that this woman they saw as a joke is outmaneuvering them. Steinem says she won’t debate Schlafly because that would give her credibility, leaving it to the deeply unpleasant and irascible Friedan, who loses her cool when they debate at Illinois State University and shouts, “I’d like to burn you at the stake!” (This really happened.) But Friedan—who, along with the racist fundamentalist Lottie Beth Hobbs, is the only character portrayed in a totally negative light, down to her twisted face and wild gray hair—deserves a lot more credit than she gets here. Not only did she write The Feminine Mystique, one of the most important nonfiction books of the 20th century, but she was also prescient. Rachel Shteir, whose biography of Friedan is forthcoming, wrote me in an e-mail, “It took [the National Organization for Women] around four or five years to realize what was going on, and then it was too late. So it’s easy to caricature Betty for her excesses, but the reality is that her ‘Geiger counter’ knew who the enemy was.”

Friedan, said Shteir, understood early on that Schlafly had grassroots appeal. The others just don’t seem to grasp that Schlafly represents actual women. The only time they seriously grapple with why conservative housewives fear the ERA is when Steinem says, “Revolutions are messy. People get left behind.” But the consensus seems to be that that’s just the way it is.

Well, maybe so. Certainly nothing would bring around the hard-core evangelicals and racists Schlafly allied herself with to grow the movement. Almost 50 years later, those people are still here, voting for Donald Trump as God’s instrument, just like King David. But anti-feminism claimed some women whom feminists should have sought to persuade, too. Although, as Jane Mansbridge writes in Why We Lost the ERA, pro-ERA activists gave conflicting and confusing responses to anxieties about drafting women and unisex bathrooms, the real issue was not these things. It was that many women raised to be traditional homemakers, supported by their husbands and respected in their communities, found their pedestals knocked out from under them practically overnight. It was not irrational for them to think the ERA would mean they would lose out in divorce, which was rampant in the 1970s, even if the laws on alimony and child custody would protect them less than they believed. Nor were they wrong to believe that the status of homemaking was being drastically lowered even as, for many of them, it was too late to choose a different path.

The segments devoted to the women’s movement raise issues that are still with us: pragmatism versus revolution, compromise versus purity, winning power inch-by-inch within the system versus raising your battle cry outside it. Bella Abzug is the practical politician. At the 1972 Democratic National Convention she pushes Steinem to abandon Shirley Chisholm, who has no chance of winning the nomination, in hopes of gaining concessions on abortion rights from McGovern. Although Abzug supports lesbian rights, she has to be argued into fighting for them. Gloria Steinem is more of a risk-taker and an idealist (“You’re a dilettante who wanted to play politics,” Abzug tells her during one of their numerous disagreements). But Steinem doesn’t need to get elected or pass bills in Congress.

Mrs. America plays deliciously with the unacknowledged common problem of both feminist and anti-feminists: men. Steinem is pornified in Screw magazine. Ruckelshaus, the lone Republican feminist portrayed, has to manage five kids and a house while her husband, a genuinely nice guy, has more important things to do. The feminists are betrayed by George McGovern and then by Jimmy Carter. On the other side, Schlafly has to massage the ego of her husband, Fred Schlafly, a prominent right-wing lawyer who is not always happy that she’s a star, even though he helps make her one. In one disturbing scene, he insists on sex when she is obviously exhausted. (Her biographer, Donald Critchlow, protested that she had a great marriage, Fred worshipped her, and he would never have done such a thing.)

Phyllis Schlafly has to contend with patronizing and exploitative male politicians, too. Her original passion was for the very male field of foreign policy; anti-feminism was the fallback. She wrote the hugely influential pro–Barry Goldwater book A Choice Not an Echo, but he doesn’t mention her in his memoirs. She backs Ronald Reagan but doesn’t get the cabinet position she thinks he promised her.

The last shot of the series shows her aproned and sad, peeling apples at her kitchen table. If only that had been the real-life end of the Phyllis Schlafly story! On the feminist side, the movement took years to recover from the defeat of the ERA. The parting frames of Mrs. America tell us that, almost four decades after the deadline, it’s been ratified in Nevada (2017), Illinois (2018), and Virginia (2020)—for the required 38 states. Resurrection or empty gesture? The battle goes on.

Katha PollittTwitterKatha Pollitt is a columnist for The Nation.