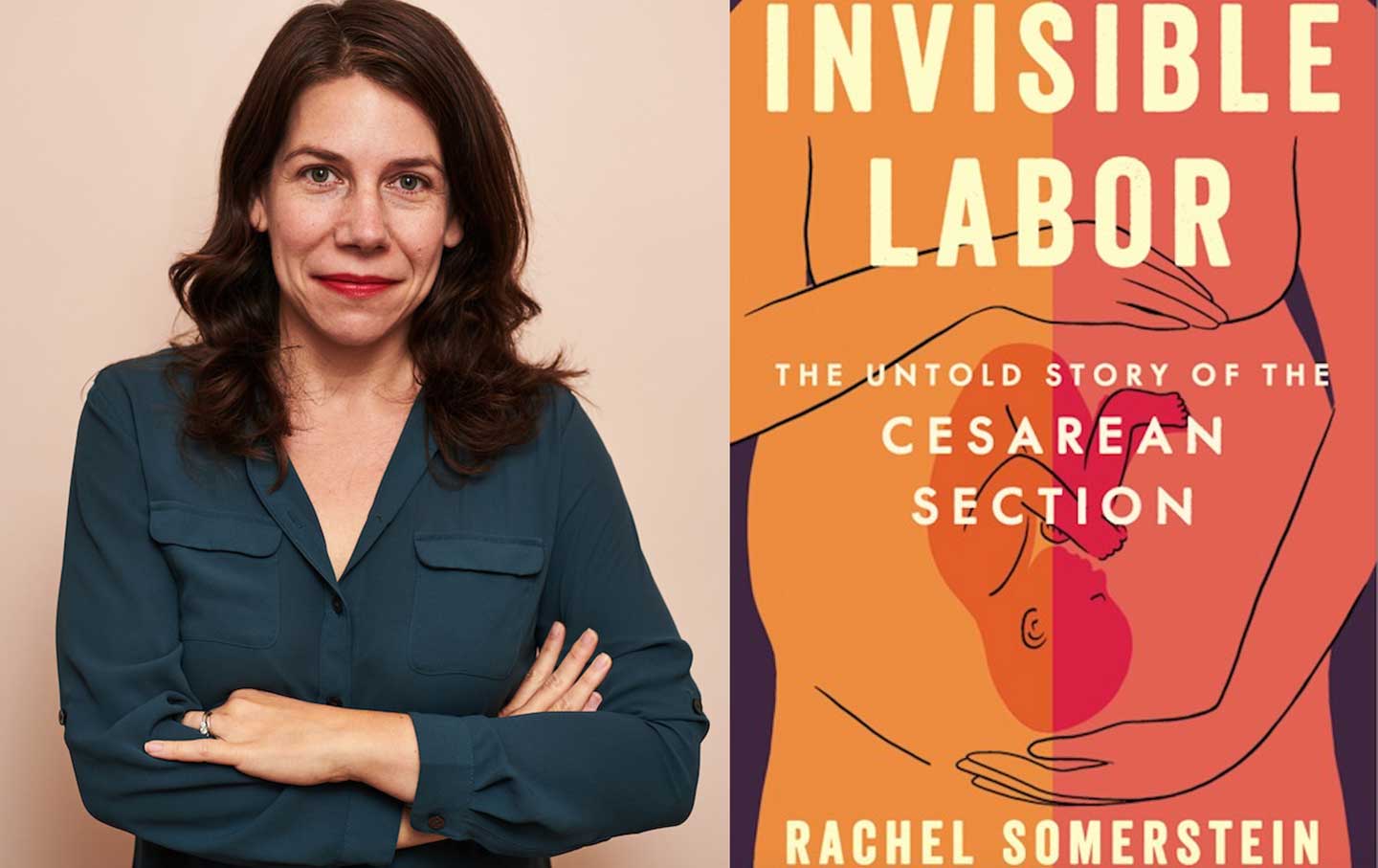

A conversation with Rachel Somerstein about her new book, Invisible Labor: The Untold Story of the Cesarean Section.

Rachel Somerstein, PhD, is a writer and associate professor of journalism at the State University of New York–New Paltz. Her new book, Invisible Labor: The Untold Story of the Cesarean Section (Ecco), is a personally intimate and rigorously-reported deep dive into reproductive care in the United States, examining how it came to look the way it does today, with specific attention paid to its roots in chattel slavery and ongoing racism, misogyny, ableism, and the rise of late capitalism. In her book, Somerstein shares the story of the labor and delivery of her first child via C-section, including the cascade of events, both personal and systemic, that led to the surgery, and the physical and emotional aftermath she has been working to investigate, and make sense of, since.

Somerstein and I sat down in our shared home region of New York’s Hudson Valley to discuss the implications of her research, how it has changed the way she approaches healthcare for herself and her children, and why reproductive rights are such an important bellwether in today’s social and political climate. Our conversation has been edited for concision and clarity.

—Sara Franklin

Sara Franklin: You’re a person who has given birth. Twice. So I want to begin by asking you, before your first pregnancy and before reporting the book, how much of this “stuff” did you know?

Rachel Somerstein: None of it. I started doing research when I was pregnant. I read Ina May Gaskin, I talked to a lot of friends who’d already had children, I read What to Expect When You’re Expecting, I joined a birth-date online group, I took a birth class that was maybe seven weeks with birthing people and their partners with my doula. None of that world of information gave any insight into what I learned when I was reporting this book.

SF: Why do you feel the C-section is uniquely suited or useful as a frame to look at larger questions of racism, classism, the dismembering of gendered bodies, and our lack of ability to connect with intuitive, or embodied, knowledge?

RS: That’s the question. I think it’s because it’s so American. It’s an aggressive intervention, and it’s heroic, actually, when it’s necessary. It can save more than one life! Yet, when you trace the history of it, it brings in enslaved people, it brings in contemporary racism, it brings in the fact that we will go to this super-aggressive intervention before we’ll go toward things that other countries are better at like preventive medicine.

What’s not in the book, that I thought about the entire time, is that it’s like climate change. We know—you cannot get somebody legitimate on the record to be like, “Humans have not changed the climate.” And yet, we cannot seem to mobilize collective action to do something about it. Why? It’s such a window into American culture. It’s capitalism, racism, patriarchy, all this. It’s the same thing with C-sections. Every single academic medical center is working to do fewer of them in a safe way. You can’t get somebody on the phone to say, “Yes, the national rate we’re doing is appropriate.” It’s a foregone conclusion that it is not. And yet, every year we’re doing more of them. What is that disconnect? It’s not about the operation. It’s about us. And, there are so many people that are really trying to move the needle. I was so mad at providers at first, but I really changed my understanding of where they’re coming from, and realized it’s their lives on the line and their occupations, too; potentially being litigated against, especially with Dobbs. There are all these people who are smart and really hard-working pushing, and yet, it’s not changing.

SF: Speaking of Dobbs, you were reporting this book through the overturn of Roe. How did that moment shape your narrative or reporting?

RS: I had already been talking to a few people who are lawyers who, probably starting six months or so before Dobbs [in June 2022], began telling me, “Roe is gone.” That made me ask what it meant to report this through the lens of reproductive justice. Because, until I was actually reporting this book, I didn’t see my experiences as a supporter of reproductive rights as whitewashed. The truth is, I always would have had the chance to have an abortion because of my positionality. There’s so much I didn’t see about what other people wouldn’t have had access to. With Dobbs, it felt like the connections that I had been trying to make theoretically by reading other people’s work and listening to other people who were long in the struggle, it was not theoretical anymore. What came on the heels of that, too, was that I needed an appendectomy when I was writing the book, and my midwife said, “You could have your tubes removed at the same time.”

SF: I actually just had that surgery, voluntarily, myself. Most providers won’t even do it. It’s so obvious to me that contraception is next. It’s already going.

The chaos and cruelty of the Trump administration reaches new lows each week.

Trump’s catastrophic “Liberation Day” has wreaked havoc on the world economy and set up yet another constitutional crisis at home. Plainclothes officers continue to abduct university students off the streets. So-called “enemy aliens” are flown abroad to a mega prison against the orders of the courts. And Signalgate promises to be the first of many incompetence scandals that expose the brutal violence at the core of the American empire.

At a time when elite universities, powerful law firms, and influential media outlets are capitulating to Trump’s intimidation, The Nation is more determined than ever before to hold the powerful to account.

In just the last month, we’ve published reporting on how Trump outsources his mass deportation agenda to other countries, exposed the administration’s appeal to obscure laws to carry out its repressive agenda, and amplified the voices of brave student activists targeted by universities.

We also continue to tell the stories of those who fight back against Trump and Musk, whether on the streets in growing protest movements, in town halls across the country, or in critical state elections—like Wisconsin’s recent state Supreme Court race—that provide a model for resisting Trumpism and prove that Musk can’t buy our democracy.

This is the journalism that matters in 2025. But we can’t do this without you. As a reader-supported publication, we rely on the support of generous donors. Please, help make our essential independent journalism possible with a donation today.

In solidarity,

The Editors

The Nation

RS: It is, that’s right. I think one reason why my midwife was trying to open this window for me, was clearly, “the window is closing on this” as Dobbs was handed down. I didn’t feel ready to do that, but part of what was clicking in was that I have the choice to be sterilized, but that nobody is going to make me. That whole array of things would not be possible for many of the people I spoke to for the book.

SF: Let’s talk about money, starting with the financialization of medicine.

RS: It is the most serious issue we’re facing in healthcare in this country. There’s a new law in Florida that you can now have a C-section outside a hospital at “advanced birth centers,” all because of a bill that was backed by a private equity firm. Because you’re in and out more quickly, it saves money. It is so incredibly dangerous.

All of the leading groups have come out against it. Research shows that when private equity gets involved, there are excess deaths, the care is worse, and multiple other metrics. That’s the kind of decision that’s being made across all the medical specialties.

SF: It is so particularly American to try to use money to avoid or minimize the impact of essential human experiences, like birth.

RS: I think it’s related to the notion of “survival of the fittest” within extreme capitalism—the idea that, rather than go through the experience of uncertainty, pain, or fear, you try to feel none of it, and just get to the other side really fast. We’re interested in the new, the “woah, what’s this pill going to do?” We’ve developed some incredible treatments, it’s amazing. But for an endurance experience like birth or chronic illness or life, you really need to be able to find non-pharmacological ways of tolerating discomfort.

SF: Let’s talk about your experience doing reporting for this book and the ways in which research on pregnancy and childbirth continues to fall short.

RS: When I first started to report out and try to place stories about the experience of not having enough pain medication in C-sections, what I ran up against was that there was no “evidence,” meaning that this had not been researched and documented in “the literature.” I told editors, “I’m not using anecdata from one person. I’ve now met enough people to know this is real, and their anesthesiologists will talk on the record about this. Spotlighting this with news is how we can push researchers to start working toward that documentation.” Also, I had chronic mastitis after my son’s birth. I had to be hospitalized. It was horrible. When I went to the academic literature to learn more about the condition, the only research was on cows. Why? Because bovine mastitis can be a problem for making money. And I was like, OK, so here’s another case of “the evidence doesn’t exist but the evidence is real.” I don’t want to say I’ve lost faith in “the literature”—scholarly processes are really important—but I have a much better understanding now of the limitations of what ends up there, how long it takes.

And lastly, because I developed PTSD after my C-section experience and had to learn how to deal with what were very disturbing physiological responses, I started—probably not even totally consciously—paying closer attention to what my body was telling me. I came to a place where I needed to attend to that and actually recognize that that is important information. Because I had to. There are things that you don’t know how you know them, and you can’t point to evidence for them, and yet, they are essential. It’s like your Spidey sense or something. People are afraid, I think, to sort of voice that except in very close relationships, this kind of “I kind of have this feeling…” And sometimes you could be wrong. But sometimes the literature’s wrong too. Or it’s silent, having overlooked real, pressing issues, particularly when it comes to women’s health, pregnancy, and reproduction.

Get unlimited access: $9.50 for six months.

SF: You quote this line that, at some point in their journey, “every birthing person loses their civil rights.” That statement really made me sit up, because it feels fundamentally true, whether it’s us or our child losing their civil rights. Given the time in which you were reporting this book—which included the pandemic years, the murder of George Floyd, the fall of Roe, these multiple, compounding structural conditions that are affecting bodily autonomy in a major way—I’m curious about whether your aperture around what it means to, or not to, have autonomy over a body has widened.

RS: If you’re born into a certain kind of body and you’re going to have certain experiences, you just can’t escape. For some people in some bodies, those will be much longer moments, and the stakes will be much greater. Post–George Floyd, post-MeToo, I would hope what we’re seeing isn’t that “your experience is my experience and I understand what it’s like to be you,” but that people who’ve believed they’re immune, the places where some of us might think we can skate by because of privilege, are not actually going to work. I go back to climate change. It’s the same thing. You can be a prepper and build your bunker on an island of your own, but you still have to breathe the same air. It’s the interconnectedness. I know it sounds clichéd. Perhaps the “agentful” way of thinking about this is, “OK, I see that I can lose my civil rights even though I have all these things that are protective, according to the literature. What does that mean for other people in the same hospital as me, potentially, that don’t have those things that are so protective?” We’re not so different. You think, “Oh, I’m in New York State and I’m done having babies, so this isn’t going to be a problem for me.”

SF: Like hell it’s not!

RS: Like hell it’s not! But it’s that thinking that “this just isn’t going to be my problem.” I was really disabused of that.

SF: One group you don’t report on in the book is birthing people who were assigned female at birth and identify as trans men.

RS: I don’t have data I can bring to that, and it’s one of the critiques I have of my own book is that it’s pretty cisgendered. What will be really interesting is how the visibility of trans men being pregnant is going to push at, and maybe explode, some of the tacit expectations of pregnant people. That, then, becomes this politically powerful thing, in a way that will probably be extremely difficult and painful for men who are pregnant, but will probably actually benefit all of us and advance the conversation. I hope.

SF: There also might be a lot of harm.

RS: Yes.

SF: How did what actually happened to you affect the way you’re trying to change the narrative around pregnancy and reproduction for the people you’re parenting?

RS: I think about it a lot. What I now know, and what I try to show especially to my daughter—she’s older—is that there are other narratives, images, possibilities for how to have a baby besides the American image of being in a hospital and there’s a male doctor and “here’s your baby.” It doesn’t even match the stats, actually. The majority of OBs now are women. Introducing to her that there are other ways. I’ve tried to be very direct with her. Not in the sense that I want to overwhelm her, but “Look at what you already know, and I’m going to turn the lights on a little bit to what you already know so that you can connect it rather than me foisting it on you.”

With pain, thinking about the ways pain is routinely dismissed, particularly for women of color, but for all women especially. So in the ER recently, for example, I said in front of her, to the provider, “She appears very calm, but she’s told me she’s in a lot of pain.” I try to model for her that she doesn’t need to be superhuman, and that she can rely on me and on her dad to help communicate her needs. Modeling that, I now don’t go to the doctor by myself. For me, that’s because of trauma, but why wouldn’t you like to have someone with you? It’s very hard to keep your head when you’re scared.

SF: It makes you so vulnerable, so susceptible, when you’re being overwhelmed by information or pain or fear or all of the above, even before you put the structures on top of it.

RS: It’s showing her that you don’t have to change who you are, and we don’t have to replicate these ways that don’t serve anybody, that don’t make for good outcomes.

Sara FranklinSara B. Franklin is a writer and professor at NYU Gallatin. She lives with her children in Kingston, N.Y.