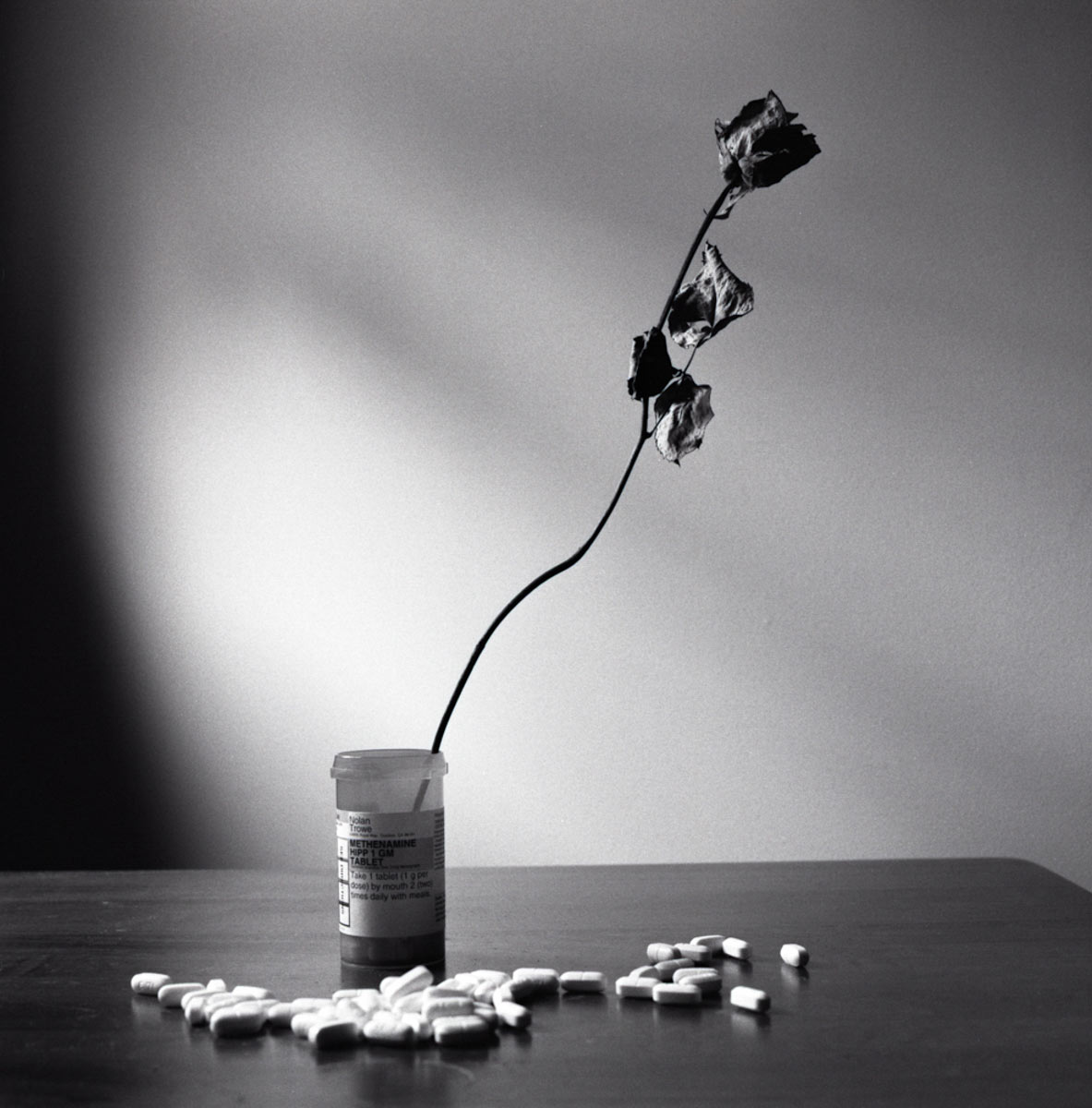

It costs me around $1,000 a month to urinate. That’s more than $30 a day. My catheters are just one of the essential medical devices that I need to survive. Since having a spinal cord injury in 2016, I have what’s called a neurogenic bladder. I can’t relieve myself without the use of an intermittent catheter, which means I have to make sure I have enough of them to get me through to the next shipment from my medical supply company.

The anxiety of rationing how many times a day you can urinate is exhausting. Imagine you only have enough supplies to go five or six times. Sure, there are the obvious physical dangers of such rationing: higher risk for urinary tract infections, dehydration, autonomic dysreflexia and so on. However, the worst part of all of it is the anguish and despair that one feels when they are running out of something that they quite frankly cannot live without. No exceptions.

In March 2020, as people scrambled about buying up all of the hand sanitizer, wipes, toilet paper, gloves, and God knows what else, I really only had two things on my mind. One, my catheters and two, my nerve medications. The pandemic highlighted for me, as it did for many people with disabilities, just how vulnerable we are when it comes to disaster preparedness. My mind reeled as more and more establishments shuttered their doors. Was the world ending? And if it was, how in the hell was I going to get my catheters? How would I survive?

At that time, everything was uncertain. Rest assured things did work out okay, but the pandemic made me realize just how quickly my world could be turned upside down, simply because I can’t pee on my own. Pharmacies put out notices for medications that were either out of stock or running low. I rely heavily on a seizure medication called pregabalin, in order to manage my neuropathy due to my spinal cord injury. I checked to see it was on the list of medications that were facing shortages, and thankfully, it wasn’t. If it was, I’d have had some of the worst withdrawals of my life. Pregabalin withdrawals are of the same ilk as opioid withdrawals.

I am far from alone in this regard. I have a handful of diabetic friends whose insurance companies basically do the same to their insulin that they do to my catheters. Talk about anxiety.

There are roughly 8 million adults in the United States who use one or more types of insulin. Analog insulin can cost more than $300 per vial, easily adding up to more than $1,000 a month. Many people often have to pay the full price of insulin because they’re uninsured or underinsured.

As a result, we are bearing witness to a deadly crisis of insulin rationing. Not only is rationing extremely dangerous in the short term, but it’s also known to have long-term and potentially lethal health complications. It’s hard to say exactly how many people in the US are rationing their insulin, but multiple studies have found that roughly a quarter of insulin users report taking that risk.

Things are being done to address the problem, but not nearly enough. Biden’s Inflation Reduction Act did put a cap on costs for Medicare patients who rely on insulin, limiting the copays to $35 a month. And while that’s a win for Medicare recipients, many of us were disappointed that the bill falls short of applying those caps to all people who rely on insulin.

As Matt McConnell wrote in The Nation this year, the consequences of rationing can be fatal, and a 2020 study found that “on average more than two people died each day in the US after being admitted into a hospital with a primary diagnosis of diabetic ketoacidosis.” And, as McConnell points out, those numbers probably underestimate the total number of these deaths, since the inpatient hospitalization data analyzed doesn’t capture the many tragic deaths that occur at home or in an ER.

Diabetics know this risk, but they have to make it work.

Another friend of mine is a bilateral amputee and has been using only his wheelchair because his pair of prosthetics no longer fit him the way they are supposed to. The fit of a prosthetic is very nuanced, and a fit that’s not quite right can lead to wounds on the limbs and subsequent infections. Unfortunately, my friend’s insurance company will cover a new pair of prosthetics only every six years, so he’s stuck with medical devices that not only are ineffective but also dangerous to his health. Of course, there are situations in which he has to use them. He finds a way to ration his legs.

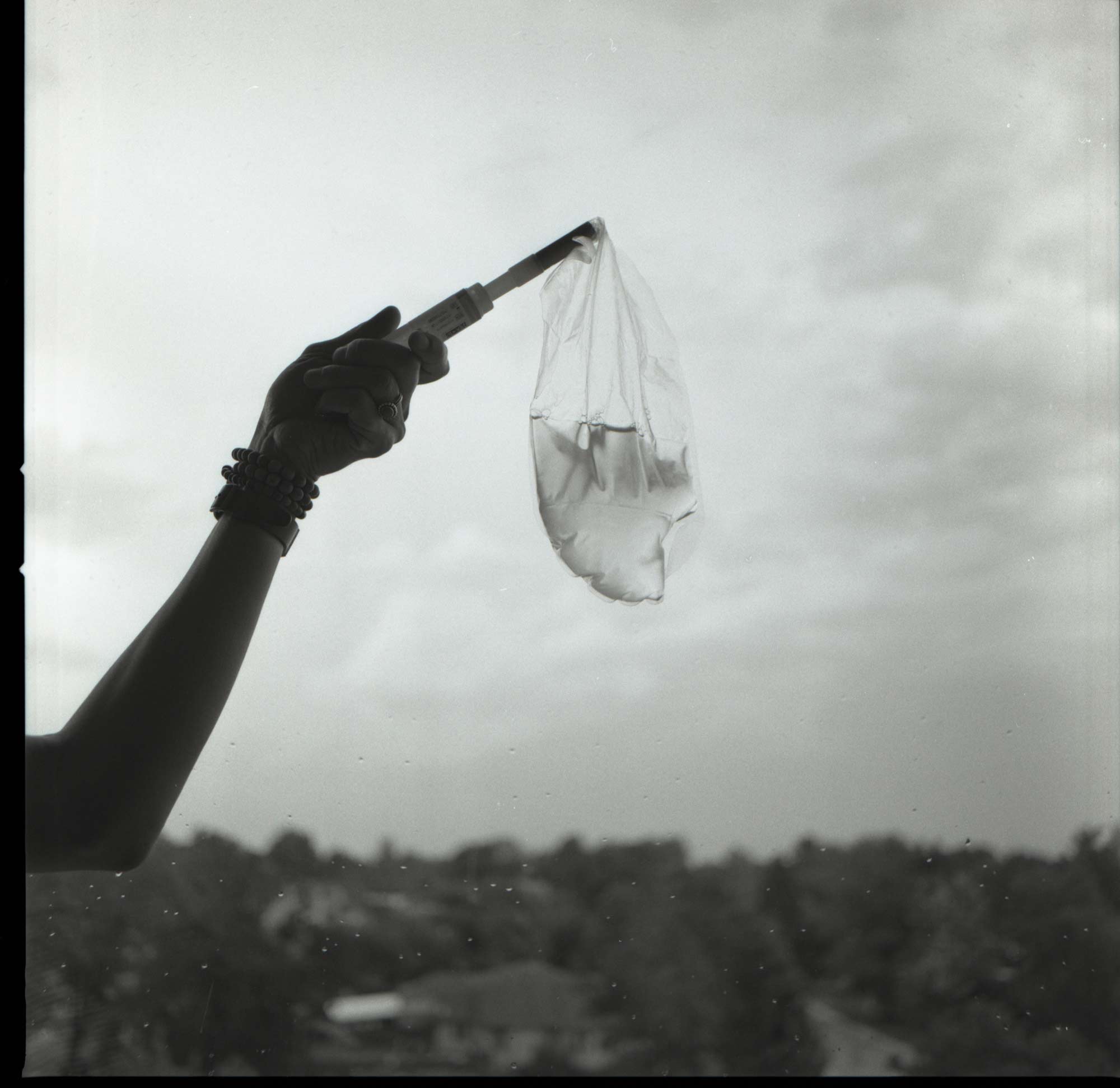

So how do we get by? The answer is community. When governments and systems fail us, it’s the people in our community who come together to make things happen for one another. During the beginning of the pandemic, a friend of mine started a Facebook page called “SCI Survivors in New York Metro Area.” During one of the most stressful and uncertain times in our history, people from the disabled community came together to offer up extra supplies they had on hand. One person ran out of catheters and made a post asking for a specific size. Within minutes, there were multiple responses from people who had enough supplies in their possession to spare a few to a peer in need.

In this Facebook group, there were ads for wheelchairs, braces, clothing, food, etc. If you were in need you could make a post, and there was someone who had your back when it felt like society did not. The page is still up and running today, and this phenomenon is not uncommon. Friends of mine who are diabetics often share their insulin supply with others who are low or are almost entirely out.

People in the disabled community are accustomed to adapting; it’s what we have to do every single day of our lives. So when society fails us, we are the ones to hold each other down. It’s a far from perfect system, but it’s one that we can rely on in times of desperation and disaster. Our lives are at stake, and we need policies to change. We can no longer be patient.