As the Threat of War Looms, Some Students Regret Joining ROTC

Often priced out of college, those in the Army ROTC can earn hefty scholarships. But reservists can’t always be guaranteed safety. “I don’t think I would’ve made the same decision.”

“We definitely couldn’t have paid for it all out of pocket,” said Jonathan Buckley, a junior at Cornell University, of his college expenses. Buckley lived in a rural town in the Midwest, and the cost of higher education was simply more than he and his family could take on. So while still in high school, Buckley did what many other college hopefuls do: He signed up for the Army.

Going to college isn’t cheap. The cost to attend some of America’s most elite universities is now north of $90,000 annually, with the average private four-year college charging more than $40,000 a year.

Priced out, young adults like Buckley are joining the armed forces to help afford a college education. As long as they pledge to serve up to eight years postgraduation, those in the Army Reserve Officers’ Training Corps (ROTC) can earn three- or four-year scholarships. Roughly 3,000 were given out last year.

Lower- and middle-income recruits often want the upward mobility that comes with a bachelor’s degree—and without the financial burden on themselves and their families. But enrolling in the Army to cut down on the staggering price of higher education comes with a catch. As the Russia-Ukraine and Israel-Hamas wars rage and the threat of Taiwan’s invasion looms, many young Americans who joined the military to avoid crippling student loan debt are wondering whether the decision to go to college could end up placing their lives in jeopardy.

“I joined because [the Army was] going to pay for my college,” Buckley said. But he likely wouldn’t have signed up if the world was as dangerous when he was in high school as it is today. “I don’t think I would’ve made the same decision, to be honest,” he admitted.

Looking back, Buckley questioned why his parents weren’t more worried about the possibility of war, which has begun to weigh on him. “Now, I kind of wonder why they weren’t more concerned about me joining the military.”

The risk of global conflict seems unsettlingly real for most Americans. According to a YouGov survey from March, 61 percent say that World War III is likely to come in the next five to 10 years. Of course, a second Donald Trump presidency could further aggravate hostilities abroad. The former commander in chief has said he would encourage Russia to attack NATO allies that are behind on their bills and refused to take a clear position on Taiwan.

Under President Joe Biden, as Iran and the militias it backs have violently defied American interests in the Mideast, it’s unclear how strong the United States’s power to deter actually is. “We don’t want to see a war with Iran. We don’t want to see a broader regional conflict,” said National Security Council spokesman John Kirby at a press briefing on Monday. But the US “will do what we have to do to defend Israel,” he said.

To make matters more complicated, only 23 percent of American young adults are eligible to serve, and in today’s strong economy, fewer are willing. Last fiscal year, the military fell short on its recruitment goals by around 41,000. The recruitment crisis is dire enough, but if college were free or affordable, there would be a far greater struggle to get young people to join. “The military totally benefits from runaway college expenses,” said Steve Beynon, a journalist for Military.com who covers difficulties facing military recruiters.

Beynon, an Afghanistan war veteran, described the educational benefits as “the most powerful recruitment tool the military has.” One of the biggest hurdles to getting would-be recruits to sign up, he said, is winning over their parents. Playing on families’ anxieties about the cost of college is a draw like no other. “Do [teenagers] really understand the concept of taking out a $100,000 loan? I don’t think so,” Beynon said. “But the parents do.”

Broadcast on cable television, the Army’s latest ad campaign revives a slogan from the 1980s and ’90s appealing to parents’ nostalgia. To parents, “Be All You Can Be” might sound reassuring, and the scholarship money might seem like a compelling incentive. The Army is promoting an optimistic message to new recruits and their families, bolstering that with expensive checks for college. But as geopolitical tensions run alarmingly high, experts aren’t sold on the idea that serving in the military is at all safe.

“There’s going to be no cozy positions in a conflict with China or if something broke out in Europe [beyond the current war in Ukraine],” Beynon said. Already, the norms of battle are shifting in unpredictable directions, giving a preview of how wars could play out in the near future. Troops today face a more complex defense landscape than perhaps ever before: understaffing, highly sophisticated weapons, an international community nearing a tipping point, and political turmoil at home in a historic election year.

With the rise of remote-controlled drone warfare and precision-guided munitions, front lines are disappearing, meaning more and more that nobody—not even reservists who are supposedly insulated from fighting—can be guaranteed safety. In January, for instance, three Army reservists were killed and dozens more service members wounded when a surprise drone strike by an Iran-backed militia hit a US outpost in northern Jordan. “Those [who were killed] were non-combat arms people in a non-combat environment,” Beynon noted.

“The unknown is obviously scary,” Jane Stewart, an Army cadet on a full scholarship at Harvard University, said of the uncertainties of being in the Army. “It doesn’t seem very tangible to me right now because I’m in college, just living a college life with a side of ROTC,” she said. “But it will become a lot more real after I graduate.”

Stewart, who was raised in a military family and said she wouldn’t have been able to attend Harvard without an Army scholarship, told The Nation that she wants to become a mother one day. “I love America, and I’m passionate about serving, but I think becoming a mom…is more important than that,” she said, reflecting on the bleak possibility of being killed in a war.

American defense planners, too, are bracing for a deadly war—this time with Beijing. In the event that a full-scale clash with China breaks out over Taiwan, “all bets are off,” said David Silbey, a professor of military history at Cornell University. He described what would be “another great-power war,” the likes of which the world hasn’t witnessed since 1945. “That’s all hands on deck. That’s everybody’s fighting—everybody’s involved,” he explained. With so many adversaries and allies caught up in battle, the only safe position in the military, Silbey said, would be “under one’s desk.”

If the risks of deployment due to jockeying superpowers weren’t enough, myriad skirmishes threatening to drag the US in are sweeping the world. The London-based International Institute for Strategic Studies reported that last year there were at least 183 local and regional armed conflicts globally, breaking records going back three decades.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →The hazards aren’t always top of mind for those considering an Army scholarship. The fact that the unemployment rate strongly correlates to military recruitment numbers suggests that, speaking broadly, “people sign up for economic reasons,” Silbey said. “Going into the military is a way to break out of their allotted sector in life.”

The question progressive policymakers have been grappling with is how to break down barriers to upward mobility, like the ones that are funneling college students into the Army. Biden’s ambitious effort to cancel student loan debt is one strategy. The Biden administration recently announced a wide-ranging program to provide relief for tens of millions of student loan borrowers, after the Supreme Court struck down his previous plan to eliminate up to $400 billion in unpaid student loans last year.

To James Pearl, a cadet on a full scholarship at New York University, the problem isn’t so much the military’s enticing benefits themselves—it’s society’s singular emphasis on higher education; it’s the steep cost of attending college; it’s how the government, through FAFSA, pushes federal loans on students; it’s how young Americans are discouraged from going into the trades. “That’s the larger issue,” Pearl said.

He told The Nation that joining the Army ROTC hadn’t occurred to him until high school, when he and his parents realized just how much debt college would bring. Pearl, now years into training, is ready for any eventuality. After all, that’s what he’s been preparing for: the unexpected. “If there does come in the future another [war], then, you know, that’s what I signed up for,” he said simply.

But Pearl’s willingness to put his life on the line doesn’t mean he isn’t worried about a global war that he could be wrapped up in, especially if Trump retakes the Oval Office. “Do I think [Trump] would press the nuclear button because he thinks he could get a small win?” Pearl asked himself. “Yeah, I do.”

Note: The names of the service members have been changed to protect their identities.

Disobey authoritarians, support The Nation

Over the past year you’ve read Nation writers like Elie Mystal, Kaveh Akbar, John Nichols, Joan Walsh, Bryce Covert, Dave Zirin, Jeet Heer, Michael T. Klare, Katha Pollitt, Amy Littlefield, Gregg Gonsalves, and Sasha Abramsky take on the Trump family’s corruption, set the record straight about Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s catastrophic Make America Healthy Again movement, survey the fallout and human cost of the DOGE wrecking ball, anticipate the Supreme Court’s dangerous antidemocratic rulings, and amplify successful tactics of resistance on the streets and in Congress.

We publish these stories because when members of our communities are being abducted, household debt is climbing, and AI data centers are causing water and electricity shortages, we have a duty as journalists to do all we can to inform the public.

In 2026, our aim is to do more than ever before—but we need your support to make that happen.

Through December 31, a generous donor will match all donations up to $75,000. That means that your contribution will be doubled, dollar for dollar. If we hit the full match, we’ll be starting 2026 with $150,000 to invest in the stories that impact real people’s lives—the kinds of stories that billionaire-owned, corporate-backed outlets aren’t covering.

With your support, our team will publish major stories that the president and his allies won’t want you to read. We’ll cover the emerging military-tech industrial complex and matters of war, peace, and surveillance, as well as the affordability crisis, hunger, housing, healthcare, the environment, attacks on reproductive rights, and much more. At the same time, we’ll imagine alternatives to Trumpian rule and uplift efforts to create a better world, here and now.

While your gift has twice the impact, I’m asking you to support The Nation with a donation today. You’ll empower the journalists, editors, and fact-checkers best equipped to hold this authoritarian administration to account.

I hope you won’t miss this moment—donate to The Nation today.

Onward,

Katrina vanden Heuvel

Editor and publisher, The Nation

More from The Nation

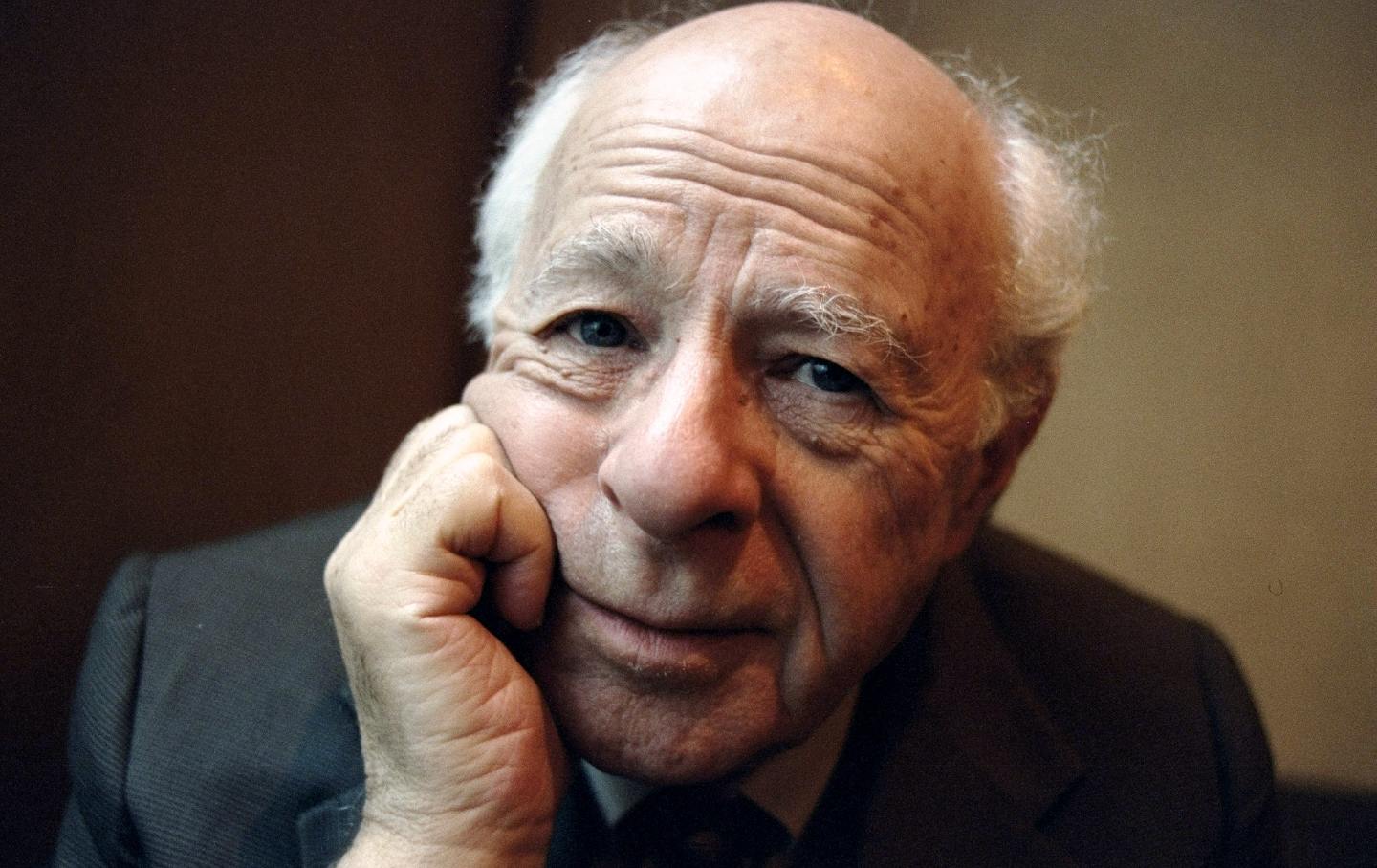

The Longest Journey Is Over The Longest Journey Is Over

With the death of Norman Podhoretz at 95, the transition from New York’s intellectual golden age to the age of grievance and provocation is complete.

The Fight to Keep New Orleans From Becoming “Everywhere Else” The Fight to Keep New Orleans From Becoming “Everywhere Else”

Twenty years after Katrina, the cultural workers who kept New Orleans alive are demanding not to be pushed aside.

Breaking the LAPD’s Choke Hold Breaking the LAPD’s Choke Hold

How the late-20th-century battles over race and policing in Los Angeles foreshadowed the Trump era.

Mayor of LA to America: “Beware!” Mayor of LA to America: “Beware!”

Trump has made Los Angeles a testing ground for military intervention on our streets. Mayor Karen Bass says her city has become an example for how to fight back.

Organized Labor at a Crossroads Organized Labor at a Crossroads

How can unions adapt to a new landscape of work?

The Epstein Survivors Are Demanding Accountability Now The Epstein Survivors Are Demanding Accountability Now

The passage of the Epstein Files Transparency Act is a big step—but its champions are keeping the pressure on.