Despite Bargaining Slowdowns, RA Unions Are Still Booming

As college costs continue to increase, undergraduate Residential Assistants are organizing for better pay and working conditions.

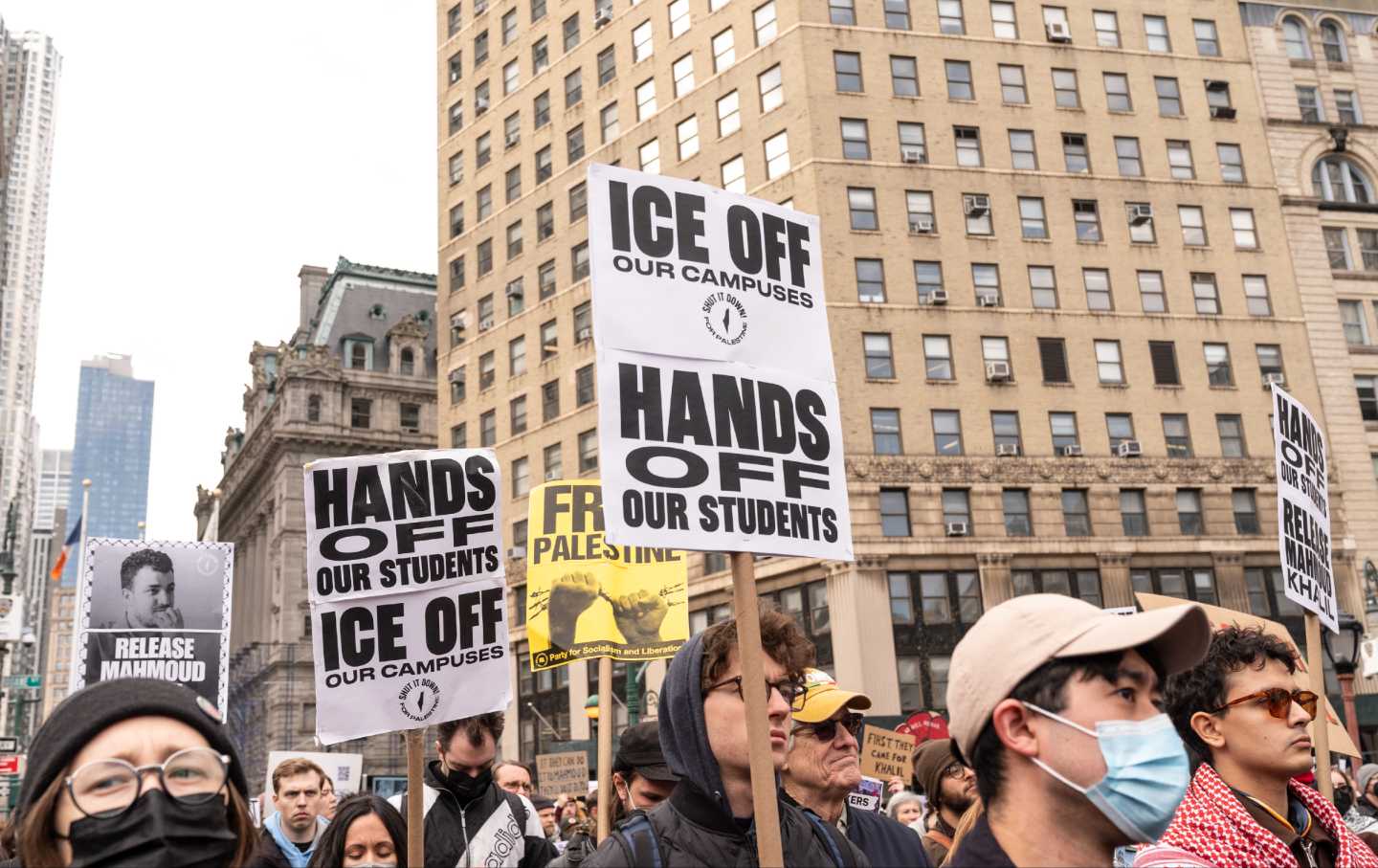

Swarthmore RAs gathered at a union rally on November 10, 2023.

(Aashish Panta)

When Mikaela Gonzalez was hired as a residential assistant (RA) at Swarthmore College in Pennsylvania, she was excited to foster community and trust in her dorm while simultaneously helping cover costs. However, she’d soon discover that the role of an RA was not as advertised.

She was not being paid enough to cover the cost of her dorm room—around $2,000 less than the $9,578 required—that serves as her workplace for constant on-call hours.

At many schools, financial aid is even considered RA compensation. At Georgetown University, RAs are paid anywhere from $1,000 if they receive financial aid to $20,000 if they do not.

Moreover, “the job itself is advertised as community-building, being there and building a sense of trust and communication with your residents,” Gonzalez said. “But when you look at the handbook and when you sign the contract, it does become clear that it is more of a surveillance job.”

Gonzalez and other Swarthmore RAs are not alone in their dissatisfaction with their role and compensation. As college costs continue to increase, many residential assistants are turning to unionizing for better pay and employer respect.

Across the United States, undergraduate RAs are organizing, helping form a historic wave of younger unionized employees. They’re demanding better pay, job security, hiring transparency, and respect from their employers, while arguing against the idea that housing costs are sufficient compensation. “Housing is simply an extension of our job,” said Bryce Merry, an RA and organizer at Bucknell University in Pennsylvania. “I am placed in a first-year dorm away from all my friends with no community of my own. I am basically on call for the students whenever they need me. I lose out on my friends, I lose out on my living situation, and I get that in exchange for this room being free.”

Hiring decisions are also an issue. According to two current RAs at Georgetown, some employees were not rehired this year for being three minutes late to meetings or clocking in for duty 10 minutes late. “We thought that was unfair,” said Sam Lovell, an RA and organizer at Georgetown.

Aayush Murarka, another Georgetown RA, had a fantastic year with a supportive community director—the full-time employee who oversees RAs—and wants to make sure his experience is common across the position. He has seen verbal abuse leveled at RAs along with seemingly arbitrary hiring decisions. “It was extremely dependent on who your community director or immediate supervisor was. Some people would get a quick meeting to clear up why someone checked into duty late. Other people would lose their job and therefore their entire education was at risk,” Murarka said. For many RAs, losing your job also means losing your housing. “It was extremely uneven and arbitrary in terms of how RAs were treated.”

RAs generally say their unionization is primarily directed toward the larger administration and housing system, not the area or community directors. At Swarthmore, three of the four area coordinators left in the middle of the 2023–24 academic year—leaving just one behind to manage all 56 RAs. Georgetown saw similar turnover, and noticed more variation in discipline and treatment with the newer hires, a major motivation for unionizing and creating stable rules.

Residential Assistant unionization campaigns have achieved historic success over the past two years, including job protections, sanctuary campuses, and new stipends. At Tufts, RAs bargained for a contract including 80 meal swipes and a $1,425 stipend, along with job protections dictating just cause for firings. “We won all those elections overwhelmingly, and I think what’s been clear is that there’s a strong demand for these workers to feel respected, to feel like the employer is listening to them. These workers want a seat at the table. They don’t want to be treated as kids. They don’t want to be treated disparagingly because of their age. They want fair pay,” said Scott Williams, an organizer with Office and Professional Employees International Union (OPEIU) Local 153, the umbrella union that has helped to form 11 RA unions and one student-worker union; the first schools to unionize include Barnard, Wesleyan, and Fordham.

Williams began organizing at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, supporting efforts by full-time public-sector college employees. Since at that time student workers were not considered to have collective bargaining rights, a separate union for undergraduate workers was never considered possible. A 2016 National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) ruling recognized graduate and undergraduate students at private universities as employees, giving life to a new strategy. Wesleyan University RAs working with full-time physical plant employees were the first to form an undergraduate student worker union after receiving voluntary recognition from their employer.

Wesleyan has been the only school to grant voluntary recognition; the other dozen, such as Rensselaer Polytechnic and Emerson, have won union elections with overwhelming support ranging from 90 to 97 percent. For most students, this is their first time participating in a union, and RAs are feeling motivated to continue unionizing post-graduation in the workforce.

Williams has seen unions connect through OPEIU to create a movement of undergraduate labor organizers, but, despite the momentum, organizers have been challenged to secure meaningful action from administrations during bargaining. “Unless the workers build power and a credible threat, and really organize and keep up the pressure, these colleges have not always been willing to bargain fairly,” said Williams.

Swarthmore students faced particular resistance, according to OPEIU organizers and RAs. Initial contract proposals containing basic rights accepted quickly at other schools—such as the University of Pennsylvania—have been considerably rewritten in delayed bargaining meetings and met with demands for no-strike clauses in return at Swarthmore. The school has continued to insist that RAs are not employees, despite other institutions and the NLRB’s asserting that they are. OPEIU has filed two rounds of Unfair Labor Practice charges against Swarthmore: the first for sudden unjust disciplinary charges given to three workers the day before the election, and the second, in mid-May, for bargaining slowdowns.

In response, RAs at Swarthmore walked out of the second bargaining session. “The bargaining process has been primarily characterized by the school dragging their feet and delaying and generally attempting to waste our time,” said Christoper Folk, an RA and organizer at Swarthmore. “This is part of their strategy to wait us out and attempt to diffuse the energy we’ve built up through our organizing.”

At UPenn, the union had been at the bargaining table since last December, and hoped to finish the contract by the end of the 2023–24 academic year. Because RAs turn over annually, organizers feel the universities have been attempting to diminish union power by stalling. Eventually, on June 10, they unanimously ratified their first contract, which included a stipend of $3,000, 20 meal swipes, and a $750 contract ratification payment for spring 2024 workers.

At Georgetown, the union got more support in the secret-ballot election than in the prior petition of support, which Lovell attributes to less fear of retaliation, even though the petition signatures were also not revealed to the school. “It’s the fear of the institution turning its eye on you and you becoming a target,” said Folk, referring to sudden citations RAs who had been involved in bargaining received. “There has not been super direct, intense repression of the RAs who unionize. Although there is repression that exists, it hasn’t been threats of termination.”

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →In 2019, the administration at Georgetown University announced pay raises for RAs the day the union was supposed to go public. After the pandemic hit, the RA contracts were terminated. Lovell is anticipating the slower bargaining that other unions have faced, but is looking forward to working with the school and stressed the union’s role as “non-adversarial.”

“We’re anticipating that it’s going to be a hard process. And that’s probably for the better. I mean, think about a contract that affects 103 people. I hope that it takes a while to talk through the nuances, that it’s a document that reflects the interests of every RA,” Lovell said. “I think it’ll be a bad thing if the university doesn’t agree with some simple terms—like no RA gets a pay cut. I think then you’re gonna see a lot of agitation.”

As the presidential election approaches, organizers fear a reshaped NLRB could undermine their strategy. If Trump wins in November, the 2016 ruling could be overturned, meaning private colleges would no longer be required to allow collective bargaining for student-employees. Lovell hopes remaining in dialogue with the university and pressing Georgetown to maintain its values as an institution will continue union recognition in the future regardless of national decisions. “I think it would be a really hard sell, not only to RAs but to the undergraduate body as a whole at Georgetown, to claim RAs weren’t employees and weren’t therefore entitled to being a member of a union.”

Swarthmore organizers are less hopeful: Clauses presented in a bargainning session on May 31 have refused to recognize RAs as employees and noted the potential NLRB changes, saying in “the event that the National Labor Relations Board or a federal court, or any equivalent entity should find that students serving as resident assistants do not qualify as employees under the National Labor Relations Act, this Agreement shall continue in force only until the date of its expiration, and then the College will have no further obligation to the Union.” OPEIU has pointed to these clauses as anti-union and anti-worker, and filed an unfair labor practice charge with the NLRB.

Regardless of national politics, Williams and OPEIU plan to continue building strong unions. “The biggest challenge we’re facing is not through the federal government’s National Labor Relations Board,” he said. “Our biggest challenge is with bargaining and the employers. Bargaining is a process that’s unfair, and where the employer maintains an unequal level of power.”

At Swarthmore, workers are steering the shape and pace of the contract, including solidarity efforts with the pro-Palestine encampment on campus and pushing back against the surveillance nature of the RA role that involves working with school safety. “We’re going to have to organize for any demands to be met, be it a better contract for RAs and other workers on this campus or for institutional divestment and to take power away from these unaccountable board members and administrators who work on their behalf,” said Folk.

“Our goal is to organize as many student workers into unions as possible. We think the best way to stop any kind of rollback of rights is to build the strongest union possible,” Williams said. “Our plan for that is not to be afraid or not to worry. It’s to keep organizing as rapidly and as strongly as possible.”

Support independent journalism that exposes oligarchs and profiteers

Donald Trump’s cruel and chaotic second term is just getting started. In his first month back in office, Trump and his lackey Elon Musk (or is it the other way around?) have proven that nothing is safe from sacrifice at the altar of unchecked power and riches.

Only robust independent journalism can cut through the noise and offer clear-eyed reporting and analysis based on principle and conscience. That’s what The Nation has done for 160 years and that’s what we’re doing now.

Our independent journalism doesn’t allow injustice to go unnoticed or unchallenged—nor will we abandon hope for a better world. Our writers, editors, and fact-checkers are working relentlessly to keep you informed and empowered when so much of the media fails to do so out of credulity, fear, or fealty.

The Nation has seen unprecedented times before. We draw strength and guidance from our history of principled progressive journalism in times of crisis, and we are committed to continuing this legacy today.

We’re aiming to raise $25,000 during our Spring Fundraising Campaign to ensure that we have the resources to expose the oligarchs and profiteers attempting to loot our republic. Stand for bold independent journalism and donate to support The Nation today.

Onward,

Katrina vanden Heuvel

Editorial Director and Publisher, The Nation

More from The Nation

“I’m Terrified”: Trans-Feminine Athletes in Their Own Words “I’m Terrified”: Trans-Feminine Athletes in Their Own Words

In part two of a series, trans women athletes describe what it’s like to compete in the Trump era.

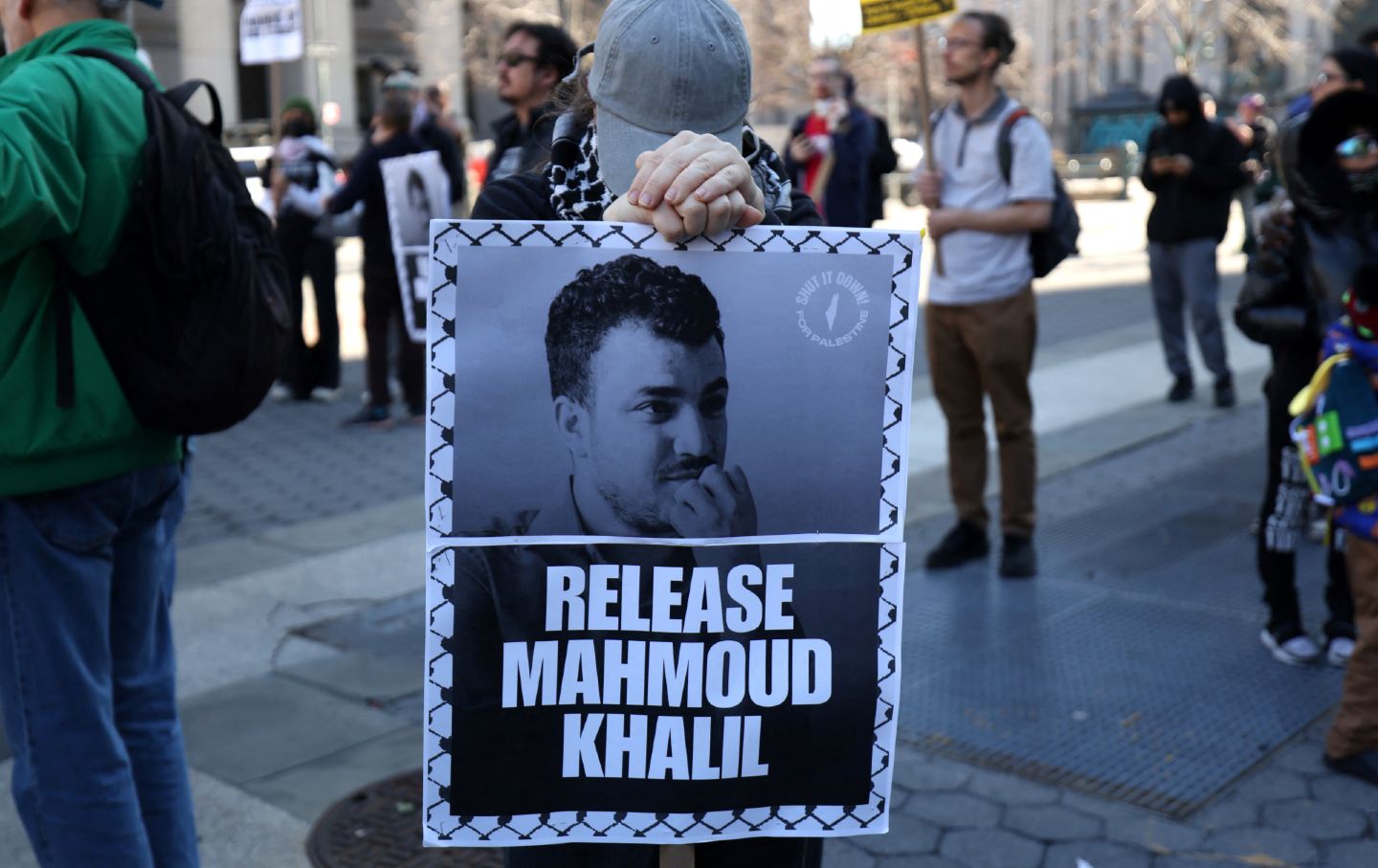

Columbia Is Betraying Its Students. We Must Change Course. Columbia Is Betraying Its Students. We Must Change Course.

The administration is choosing complicity over courage in the case of Mahmoud Khalil. It’s time for the faculty to demand a new path.

The Trans Cult Who Believes AI Will Either Save Us—or Kill Us All The Trans Cult Who Believes AI Will Either Save Us—or Kill Us All

What the Zizians, a trans vegan cult allegedly behind multiple murders, can teach us about radicalization and our tech-addled politics.

We Are Asking the Wrong Questions About Mahmoud Khalil’s Arrest We Are Asking the Wrong Questions About Mahmoud Khalil’s Arrest

The only relevant question is not “How can the government do this?” It is “How can we who oppose this fascist regime stop it?”

DOGE’s Private-Equity Playbook DOGE’s Private-Equity Playbook

Elon Musk's rampage through the government is a classic PE takeover, replete with bogus numbers and sociopathic executives.

Parts of LA Are Not Going to Be Habitable Parts of LA Are Not Going to Be Habitable

Insurers have figured out that risk is too high in parts of California. We need to re-conceive how people are housed, and fast.