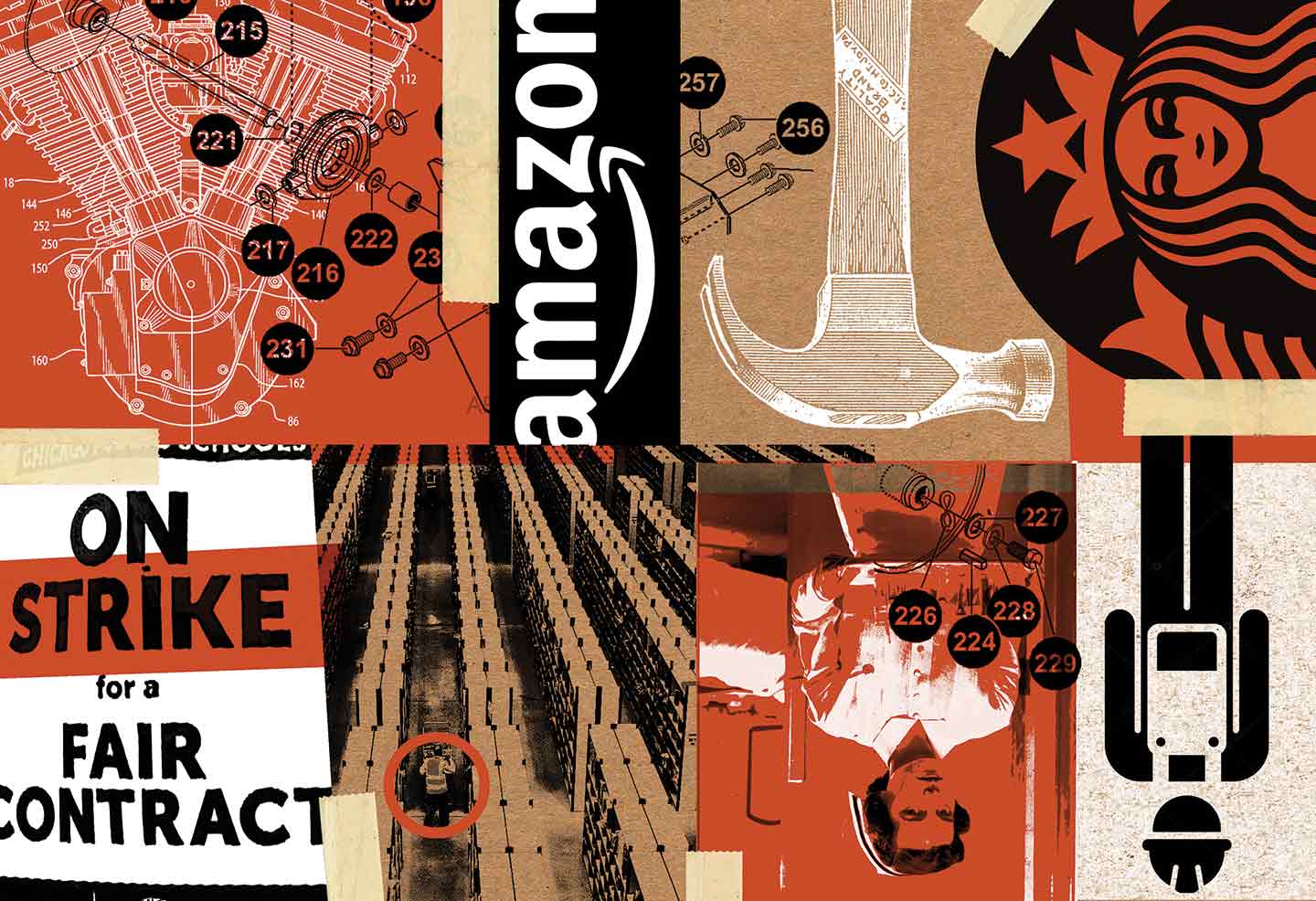

Illustration by Tim Robinson.

“No one wants to work anymore” was the surprise refrain of late 2021, posted on the doors of businesses forced to close for lack of staff and delightedly memed by a burgeoning anti-work crowd online. Reddit’s r/antiwork subgroup, the clearinghouse for cathartic quitting stories and texts to horrible bosses, became so popular it warranted a report from the Financial Times. If the early days of the Covid-19 pandemic were marked by astonishing unemployment rates as businesses closed down and fired or furloughed staff, so many people quit their jobs in 2021 that the phenomenon acquired its own nickname: the Great Resignation. Baristas, the quintessential service workers, have won unionization campaigns at Starbucks franchises across the country; in April 2022, warehouse workers on Staten Island finally struck a blow against the seemingly invincible Amazon. Wages for American workers have risen rapidly, a novelty after decades of stagnation. But what should we take from these recent developments in the politics of labor? Are they aftershocks of the pandemic alone, or are they indicative of broader trends?

Neither Aaron Benanav’s Automation and the Future of Work nor Sarah Jaffe’s Work Won’t Love You Back was written with the pandemic in mind, but together they serve as an indispensable guide to the broader dynamics of work in the contemporary moment. Benanav tackles the question of what caused deindustrialization and the unemployment associated with it; Jaffe examines the kinds of work that have followed in its wake. They offer a portrait of work in the aftermath of the industrial age that has long defined it, without resorting to the frequently expressed nostalgia for the bygone days when real men made real things. In the process, each provides an astute assessment of the conditions of work today and a glimpse of a future in which we’d have a different relationship with work altogether. But they present radically different views of the prospects for labor in the near term: Benanav suggests that labor’s position relative to capital is steadily weakening, while Jaffe argues that a new working class is becoming conscious of its potential power.

Automation and the Future of Work is a short book of just under 100 pages that expands on two articles published in New Left Review. The problem that Benanav takes up is a familiar one: Present tight labor markets notwithstanding, “there are simply too few jobs for too many people.” In particular, there are not enough good jobs to go around. Work was defined in the first half of the 20th century by the rise of mass industrial employment, and in the latter half by its decline. Deindustrialization tends to conjure a whole social world—the specter of the Rust Belt and vacant cities. But technically, it is a measurement of a decreasing share of manufacturing jobs assessed in relation to total employment. As manufacturing jobs have disappeared, full-time jobs with good wages and benefits have become hard to find—but low-wage, part-time, insecure jobs, mostly in the service sector, are plentiful. The result is that many people are employed but are still struggling to get by. While deindustrialization is often treated as something that affects the so-called developed countries of Western Europe and the United States most severely, Benanav shows that it is a global phenomenon: The waning of manufacturing jobs has changed the dynamics of work everywhere. Why, he asks, has the relative number of manufacturing jobs declined so starkly? And why has this decline had such widespread social consequences?

There are two usual explanations. The most familiar story emphasizes offshoring in the wake of globalization, charging that companies once based in high-wage countries like the United States have moved production to places like China and Bangladesh, where labor costs are drastically lower. This story is about job relocation rather than job loss: Workers in the US and Western Europe are the losers, while workers in East Asia are the winners. The other focuses on technology: Automation theorists hold that technological advances have increased productivity and reduced the need for workers altogether. Manufacturing has borne the brunt thus far, but artificial intelligence, they claim, threatens to replace many more jobs in the service sector, as well as in many professional fields. One widely cited study estimates that 47 percent of jobs are at risk of being automated. Many automation theorists are Silicon Valley tech boosters, who are thrilled by new advances in AI and information technology and concerned about their social consequences as an afterthought (think Andrew Yang). But Benanav also identifies automation theorists on the left—thinkers like Aaron Bastani, Peter Frase, Nick Srnicek, and Alex Williams—who see in automation the potential for a post-work, post-scarcity future, if we can only seize control of the robots. Capitalists, they argue, use technology to replace workers without giving them another way to get by. But if we collectively owned those technologies, we could use them to eliminate unpleasant work while guaranteeing everyone a good standard of living. Jobs are not the source of dignity and worth, as the left has often claimed, but simply a way to earn an income: No one really wants to spend eight hours a day in a factory. If jobs and income were delinked, job loss would be a good thing—the sign of a society with more free time. This basic premise has made the idea of a universal basic income popular among techno-optimist radicals and Silicon Valley futurists alike.

Benanav accepts the core thesis that industrial employment has declined and, with it, the availability of good jobs. But he offers a different explanation, one rooted in the overarching dynamics of global capitalism since the 1970s. While automation theorists contend that technology-driven productivity increases have displaced workers, Benanav points out that productivity growth rates have declined from their postwar peaks. Drawing on the historian Robert Brenner’s theory of the “long downturn,” Benanav argues that deindustrialization has been caused by global “manufacturing overcapacity.” Simply put, the world makes more goods than it can or will buy. In the immediate aftermath of World War II, US manufacturers had few serious competitors. But as other countries built their manufacturing sectors, often as part of intentional development strategies, the field became crowded. Competition among producers increased, driving down prices for goods and wages for workers. Lower prices, in turn, decreased rates of profit, which dissuaded capital from investing in greater productive capacity, eventually leading to a decline in output and, in turn, a decline in the number of manufacturing jobs. This decline, Benanav notes, typically indexes the health of the economy writ large: When the manufacturing engine slows, the whole economy tends to stagnate.

Nor have Rust Belt jobs simply moved elsewhere, Benanav observes. Rather, the phenomenon of “overcapacity” is a global one that has caused a manufacturing decline worldwide. The “stagist” view propagated by mid-century modernization theorists imagined that every country in the world would develop from an agrarian to an industrial economy along the historical path of Western Europe and the US. Benanav argues that instead, economic development is going in the opposite direction: As the work of economists like Dani Rodrik shows, the current trajectory around the world is one of deindustrialization spreading prematurely—even in China, now the world’s industrial powerhouse. There aren’t enough jobs anywhere.

Low demand for labor isn’t particularly novel in itself. Benanav writes that the 20th-century boom in manufacturing and, consequently, in employment, was an exception to the norm in the history of capitalism. The present low demand for labor in some ways recalls the conditions of the late 19th century, before the rise of mass production and employment. The critical difference is that today’s laborers have little to fall back on—no family farm, no subsistence plot. The world is now largely deagrarianizing and deindustrializing, leaving workers more adrift than ever before. To make matters worse, while many Western capitalist countries once offered robust safety nets for the temporarily unemployed, over the past quarter century they have stripped their social supports to the bone. It is hard today to be completely unemployed and survive. Even those who are employed often find it difficult to get by. Large numbers of workers today are underemployed even if they technically hold jobs—working part-time at jobs that offer low wages and meager (if any) benefits, often under poor conditions and with little in the way of protections. In many countries, particularly in Asia and Africa, a majority of workers are in informal or vulnerable employment; around the world, women, young people, and migrants are more likely to do temporary and part-time work. The International Labor Organization reports that nonstandard conditions are creeping into industries once defined by standard work, including manufacturing. In other words, for much of the world, nonstandard employment is the standard. Benanav estimates that the service sector has absorbed an astonishing “74 percent of workers in high-income countries, and 52 percent worldwide.” Even given this remarkable boom in service work, nothing has managed to replace manufacturing “as a major economic-growth engine.”

In manufacturing, productivity gains come from the introduction of new technology, which makes it possible to produce more goods per worker. But it is harder to increase productivity rates in services: They are by definition labor-intensive activities in which one person does something for another. Service sectors therefore rely on wage suppression rather than automation to keep services cheap and demand high. In turn, service jobs have mushroomed in recent years primarily because wages have been low enough that the relatively well-off can afford to farm out tasks to temporary servants. But Instacart and DoorDash are not going to generate a new age of prosperity à la Ford and GM. There’s a reason nearly every country has sought to build its wealth by developing its manufacturing sector.

For Benanav, then, the collapse of industrial employment and the replacement of the mass industrial workforce with legions of underemployed service providers demands a reevaluation of capitalism’s trajectory. No future age of global full employment awaits us, no moment when the conditions of Western postwar life will be realized worldwide. Instead, the existing reality in much of the Global South—pervasive underemployment paired with a massive low-wage service sector, much of it informal—is the future that now awaits the wealthy West as well. Capitalism will not, and cannot, create enough jobs to gainfully employ the billions of people who are dependent on it to survive. The problem isn’t just automation or globalization; it is that the system itself is running out of steam.

It is the struggles of workers in these other sectors, and the service sector in particular, that occupy Sarah Jaffe’s Work Won’t Love You Back. Jaffe is concerned with what comes after deindustrialization—with the jobs that have replaced manufacturing and the people who do them. Combining reportage with theoretical inquiry, Work Won’t Love You Back is at once a dispatch on the conditions of work in the United States today, an examination of a burgeoning class consciousness within a new working class, and a Marxist-feminist disquisition on the role of emotion in labor.

Where Benanav’s argument rests on productivity charts, Jaffe’s is built on empirical evidence that is more granular, drawn from years of labor reporting for outlets including The Nation, The New Republic, Dissent, and others. Each of the core chapters considers a different kind of work, ranging from domestic to retail to video game development; each is anchored by the story of a particular worker, set in the context of a longer labor history and analyzed through the work of theorists like Nancy Fraser and Angela Davis. Crucially, Jaffe also highlights what people are doing to change the conditions of their work: domestic workers organizing for a federal domestic workers’ bill of rights; athletes, art workers, and academics unionizing; teachers striking.

What makes the service sector different from manufacturing, in Jaffe’s account, is the ideology that governs it: Employers in the service sector expect workers to “show up with a smile on [their] face.” The sociologist Arlie Hochschild famously described the work of controlling one’s emotions in order to produce a particular affective response in customers as “emotional labor,” but Jaffe develops a more general thesis about affect and labor in the postindustrial era. Today, work is insecure, flexible, and underpaid—and workers are expected to enthuse about it, to perform it eagerly, even to love it. Love, Jaffe explains, is how capitalism justifies itself in the neoliberal era; it is how capitalism motivates and disciplines workers even as it suppresses wages. If Benanav offers a theory of why service work tends to be so poorly paid, Jaffe offers a theory of how it is that workers are compelled to work so cheaply. This kind of work has its own symptoms and workplace injuries: Jaffe diagnoses burnout, for example, as “a problem of the age of the labor of love.” But it also has its own possibilities, rooted in the disjuncture between what people actually want and what work offers.

The first half of Jaffe’s book considers how love operates in the kinds of jobs frequently thought of as “women’s work”: teaching, cleaning, caring, nonprofit work. As Jaffe points out, the distinctively human abilities that make service work hard to automate are rarely recognized as skills at all. Rather, they are typically treated as natural capacities of certain kinds of people—namely, women. Jaffe begins by exploring the unpaid work done in the family itself, usually by women, and develops the book’s core thesis with reference to Hochschild and other feminist thinkers—most significantly, those in the tradition of Wages for Housework, whose central claim is that love is a way of disguising work. Subsequent chapters show how, although much of the work once done for free in the household has moved beyond it and is now done for pay primarily by women of color, love continues to operate as a form of labor discipline. Paid cleaners and nannies are the most obvious surrogates for housewives. But teachers, nonprofit employees, and retail workers, each in their own way, put to work skills taught in the family: to serve others selflessly; to comfort and soothe; to absorb negativity; to clean up messes; to make people feel better—in short, to be everyone’s mommy. In these kinds of jobs, love is invoked to squeeze out more work with less pay. When teachers or nonprofit workers ask for a raise, they are told to think of their students or clients. Retail workers fit a bit uneasily into this category: Walmart may say that it’s a family, but it is doubtful that many cashiers see their jobs as a vocation. Retail workers are nevertheless compelled to pretend they love their work, to smile and do whatever it takes to keep customers happy.

The second half of Jaffe’s book considers a very different kind of work—work that is treated as creative, fulfilling, and rewarding. In other words, work seen as worthy of love. These desirable kinds of work constitute the other strand of “the labor-of-love narrative”—love as creative passion. This kind of love is gendered differently, typically associated with the single-minded male creator rather than the self-abnegating female caregiver. But these kinds of love are ultimately two sides of the same coin: “The romantic attachment of the artist to his work is the counterpart of the familial love women are supposed to have for caring work,” Jaffe argues, even as the fantasy of the solitary genius denies the necessary role that care plays in producing creative work. In fact, the ideal of toiling for the love of the work itself is no less effective in compelling unpaid labor than the ideal of sacrificing oneself for the love of others. Workers employed in the studios of name-brand artists produce pieces that sell for millions while aspiring to make their own art one day. Academia promises a life devoted to the mind, yet adjuncts scrambling to teach classes across multiple campuses can only dream of devoting time to their own research. Athletes are told they are lucky to play games for a living, even as the intensity of competition wears their bodies down and leaves them with lasting injuries. Programmers work such long hours developing video games that they no longer have time to play them. Many interns even work for free in the hope of one day landing a job in their desired field. These workers are told to be grateful they have jobs at all and are warned not to ask for more—or, in some cases, for anything at all.

What unifies these various labors of love, for Jaffe, is a rhetorical and ideological trick. In all of these cases, work is described as something else—play, self-expression, family—such that many workers in postindustrial society have to fight simply to have “their work recognized and valued as work.” If work isn’t named as such, however, love has the opposite problem: It is named where it isn’t actually present. Drawing on a key tenet of Wages for Housework, Jaffe seeks to demystify love. When love becomes a tool for compelling us to work, she writes, “love” isn’t really love at all.

As Jaffe shows, there often is real love at work on the job—of nannies for the children they care for, teachers for their students, coworkers for one another. But love is a relationship between people; it is something “reciprocal.” Work is not a person, and as Jaffe notes, it “never, ever, loves you back.” So when we are told to “love our work,” we lose track of what and whom we really love. When we are forced to work more or odder hours, or asked to be perpetually on call for potential shifts, we struggle to spend time with one another. We need to make work better, of course. But, Jaffe thinks, channeling the Wages for Housework thinker Silvia Federici and anti-work feminist theorist Kathi Weeks, that we also need to refuse work outright in favor of something more valuable: our lives and our relationships to each other. This calls for a shift in consciousness, a recognition that “our lives are ours to do with what we will.” Dispelling the mythology of loving our jobs is a necessary step toward discovering what love really is and could be.

Automation and the Future of Work and Work Won’t Love You Back make a neat pair: The former explores the process of deindustrialization in broad strokes while the latter analyzes in greater detail the forms of work that have filled the gap. Yet their differences are not only a matter of subject or perspective. The books also diverge in their diagnoses of what ails capitalism today and, in turn, in their prescriptions for what might be done about it. Capital and its pursuit of returns are the driving force of Benanav’s story; workers and their class consciousness are that of Jaffe’s. Benanav’s critique of capitalism is that it cannot create enough jobs; Jaffe’s is that we don’t want the jobs it does create.

These differences come to the fore most clearly in Jaffe’s and Benanav’s divergent accounts of the postwar moment, which both recognize as an exceptional period in the history of capitalism in terms of relative equality and worker power, even as both caution against nostalgia for it. Like Benanav, Jaffe argues that “fewer of us than ever are needed to produce what is necessary for human flourishing,” emphasizing the role of automation and outsourcing in the decline of manufacturing jobs in the 1970s. But for Jaffe, although the “golden age” of capitalism coincided with the golden age of industrial employment, there is nothing inherently distinctive about manufacturing. The kinds of industrial jobs now often romanticized as “real work”—on an assembly line or in a coal mine—were usually miserable, alienating, exhausting, and dangerous. What made these jobs relatively good ones is the fact that they were unionized and, as a result, well-paid and well-regulated. In other words, it was workers themselves who made these jobs into what we now think of as standard employment. There is no reason that today’s working class—more diverse in terms of race and gender than that of the mid-century; more likely to work in a hospital or a big box store than in a factory—can’t organize to make their jobs equally good ones.

Benanav, by contrast, claims that manufacturing work is different, and that this difference is not only a matter of who does it or how it is paid. In Benanav’s account, manufacturing really is—or, at least, was—the only kind of industry that could sustain the level of productivity and growth necessary for mass employment and prosperity. In his view, it is not a coincidence that the golden age of capitalism represented the peak of industrial employment. The growth of other kinds of work can never replace industrial employment, either as a source of profits or of good jobs. In the low-productivity sectors that have replaced manufacturing, Benanav argues, “the dynamic struggles that animated earlier generations of workers” over how the benefits of productivity growth would be distributed no longer occur. Workers still struggle, but the “logic” of these struggles has shifted. What is this new logic? Benanav doesn’t say. But his analysis implicitly raises a challenge to the premise of Jaffe’s book: Could the workers whose struggles she depicts actually build the power to challenge the broader conditions of work under capitalism, let alone capital’s control over production?

After all, most of the work considered in Work Won’t Love You Back is concentrated in the public or nonprofit sector or done for small-scale private employers in the relative isolation of private homes and studios. Retail work, pro sports, and game development are the only industries addressed in which private capital employs workers directly and en masse; the latter two are arguably the only ones in which the workers in question are central to the production of the goods being sold. If manufacturing really is distinctively productive, as Benanav sees it, then struggles over domestic and nonprofit work—perhaps even those in the retail sector and athletics—are ultimately struggles around the margins. They can’t shut down production in the most dynamic sectors of the economy. Tech workers might be the exception, and indeed, Jaffe suggests that “tech workers might have more in common with the industrial workers of midcentury” than one would expect. Yet tech workers are also the most distinctive of Jaffe’s case studies, employed by an industry that, although it exploits workers’ enthusiasm for its products, also pays them handsomely and rakes in profits. Love may at times be doing too much work to make Jaffe’s own narrative cohere: Many kinds of bosses try to substitute love for money, after all, but the various workers cajoled in this fashion stand in starkly different positions to one another.

If Benanav’s account casts doubt on the ability of service workers to exert the political force once held by the industrial working class, does he offer any alternative possibilities for class struggle? Rather than address worker self-organization directly, Benanav offers a critique of the two policies most often proposed as solutions to the low demand for labor: a universal basic income (UBI), to address the problem of unemployment caused by technology, as it is understood by automation theorists; and Keynesianism, to address the problem of overcapacity that he himself has identified.

Benanav paints a UBI as a “silver bullet” aimed at the wrong problem: the rise of automation rather than the collapse of manufacturing work throughout the world. A UBI in a particular country might alleviate some of the harmful effects of underemployment, but in order to have the genuinely transformative effects that its left proponents imagine, it must empower workers and social movements to demand more than a minimal check. But it is hard to see how a UBI would come about without those kinds of movements in the first place. For Benanav, left-wing UBI enthusiasts face another problem: The UBI does not challenge capital’s control over investment. It may distribute wealth more broadly, but it leaves the forces that generate wealth in private hands. It is therefore hard to see how a UBI could really constitute a “capitalist road to communism,” as some of its champions have suggested. Rather, it seems more likely to be a sop to the poor in a world still run by private investors.

Keynesians, by contrast, speak more directly to the issue of manufacturing decline, seeing it as a problem of underinvestment that can be solved by using state spending to stimulate demand. Yet Benanav contends that Keynesian measures have already been tried and have failed to solve the problem. Keynesian spending, in his account, was surprisingly little in evidence during the postwar boom in Western Europe and the US, which was led and sustained by private rather than public investment: Instead of spending countercyclically, governments used the revenue from private sector growth to pay down their debts. It was only during the 1970s downturn that debt-to-GDP ratios exploded—but growing public sector spending has done little to stem the tide of deindustrialization.

In Benanav’s view, a different Keynes is needed today—not the Keynes who called for stimulating labor demand via deficit spending, but the Keynes who called for reducing labor time, famously envisioning a 15-hour workweek nearly a century ago. Yet to finally achieve that aim would require socializing investment: The state would have to decide what and how much to produce, and direct resources accordingly. Such a project would, of course, be vigorously resisted by those who currently control production and profit from private investment. Only if social movements are powerful enough to bring capital to heel, Benanav maintains, can the dreams of this radical Keynes be realized. But if social movements are that powerful, he asks, why stop with reforms? Why not simply continue on to communism?

Ultimately, Benanav tells us, both radical Keynesians and UBI advocates must have an answer to capital’s own political tool: the capital strike. Capitalists can cause the economy to grind to a halt by refusing to invest until their political demands are met. This threat is potent, Benanav believes, since “capital disinvestment neuters all worker-empowering policies as soon as they are born.” The implied conclusion is stark: Worker power is necessary to challenge capital, but workers cannot build that kind of power in the aftermath of deindustrialization. Here, as elsewhere, Benanav’s political analysis is derived from first principles read through productivity statistics: If workers have power, then revolution follows; if not, then stagnation results. While this pared-down account is useful in grasping the general dynamics of capitalism today, it is less helpful in illuminating the many possible conditions that fall between these two poles. It can also make the outcome of any prospective struggle appear settled in advance: If the moment when workers could build power has definitively passed, why bother with collective action at all? (In fact, many in the Endnotes collective with which Benanav is associated have drawn precisely this conclusion.) But this thin account of politics is more of a problem for Benanav’s argument than he acknowledges: Although he suggests that capitalism is reaching the point of exhaustion, he does not actually argue that it will collapse from within. His argument, instead, is that capitalism will increasingly fail to meet people’s expectations for a decent life. It is, in other words, fundamentally a moral argument about what is wrong with capitalism, but without a corresponding theory of how a political challenge to it might be generated.

On the other hand, we might reasonably wonder why capital isn’t trying harder to resolve its profitability crisis. Although Benanav thinks that Keynesian policy has failed, the historian Tim Barker, among other scholars, has pointed out that governments in recent decades have not really tried it. They have leaned on monetary policy—namely, low interest rates—rather than utilizing the most traditional Keynesian tool of fiscal stimulus: i.e., massive government spending, particularly in the form of public investment. The obstacles to the latter are steadfastly political, as Benanav himself notes with reference to the work of the economist Michal Kalecki on the political dimensions of fiscal policy. Even though public investment might help alleviate stagnation, Kalecki argues, capitalists will resist any challenge to their power to control investment. But this doesn’t fully explain many of the political challenges we currently face—for example, why even recent efforts to stimulate, rather than supplant, private investment through public spending have been so paltry and hard-won.

In the past two and a half years, of course, states have shut down economies to a remarkable degree and have spent more than the most radical Keynesians might have expected, even while steadfastly declining to exert greater control of production outright. Extended unemployment assistance, state-paid furloughs, and stimulus checks—in effect, UBI one-offs—have made it possible for many people to live without working, at least temporarily. For older workers with retirement accounts, meanwhile, skyrocketing asset prices have eased the way to early retirement. The result has been a remarkable shift in the balance of power between labor and capital: Much of the United States and the European Union are now experiencing worker shortages, giving workers new leverage. State spending may not have eliminated the compulsion to work altogether, but it has given people more breathing room, thus far with striking political effects.

The obvious conclusion is to see these developments as a vindication of Jaffe’s analysis and a rebuke to Benanav’s. Many people, it would seem, have realized that work does not love them back—work does not care if they get sick or even die. No one wants to work anymore? No one ever really did, Jaffe might argue. She has since reported on the much-heralded surge of labor militancy, visible in strikes at workplaces ranging from the John Deere factory, where 10,000 workers walked out for six weeks, to Saint Vincent Hospital in Worcester, Mass., where nurses struck for an astonishing 10 months. As Jaffe told The New York Times regarding the latter, “They’re watching the hospital cut costs and lay off nurses after getting CARES Act funding, and they’re just going, enough is enough. We can’t keep working in these conditions.”

But the recent workforce crunch in some parts of the world does not refute Benanav’s thesis so much as add a twist to it. It is still true that in the long run, capital will likely need fewer and fewer workers, and it is unlikely that this dynamic will be reversed altogether. (This does not necessarily mean, however, that the ratio of jobs to possible workers—the size of the surplus population, in Marxian terms—will always be as stark as it is now: Demographic patterns, most significantly slowing population growth, will also affect labor markets.) Although the genuinely unprecedented response to Covid-19, from the enforced economic shutdowns to massive state support for both closed businesses and unemployed workers, has altered the terrain of labor struggle, the most dramatic claims about a “strike wave” and a Great Resignation are likely overblown. Paradoxically, the current burst of organizing and the resulting rise in wages may be what finally drives the (partial) automation of some service industry jobs—think of the rise of the restaurant QR code as a labor-saving device. The tight labor market may be short-lived if the Federal Reserve continues to respond to inflation by hiking interest rates. But what the experience of Covid does reveal is that the political consequences of a generally low demand for labor are not as predetermined as Benanav’s stripped-down account tends to suggest.

If the pandemic and its downstream effects have, however temporarily and unevenly, emboldened at least some workers to take on the boss, Benanav and Jaffe ultimately aim toward more sweeping transformations of work and of society in general. Benanav suggests that the left once had clear ambitions, as expressed by Brecht: “Our goal lay far in the distance / it was clearly visible.” By contrast, he writes, contemporary movements “lack a concrete idea of a real alternative.” The closing chapter of Automation and the Future of Work therefore outlines a vision of a “post-scarcity” society achieved not through the sheer quantity of goods but through the social commitment to meeting everyone’s needs. We can use technology to reduce some work and share what remains, Benanav asserts, while expanding everyone’s access to what Marx famously called the “realm of freedom,” where we can spend our time as we will. Jaffe, too, wants us to work less and love one another more. She is more sympathetic to a basic income scheme than Benanav and less prescriptive of the world to come, but their visions share broad outlines—less (and more evenly distributed) work, more free time. More freedom, less necessity. Indeed, this demand—for time, for the freedom to live our lives as we will—is, contra Benanav, perhaps the core animating vision of the Western left today.

It is a compelling one. The problem, however, is not so much the lack of visions as the lack of power with which to realize them. The goal in the distance is still more clearly visible than any road that would plausibly lead there. And like the Endnotes project writ large, Automation and the Future of Work struggles to convincingly pivot from its unsparing diagnosis to a compelling account of political action. After 80 pages of closely parsed productivity statistics and ruthless critique, the swerve, in this final chapter, to a soft-focus vision of a communist utopia is jarring. Benanav mostly sidesteps the question he puts to other thinkers—where might the power to challenge capital’s control over production come from?—gesturing only briefly in a postscript to the various struggles that have swept the world since 2008, while also immediately outlining their limitations. The result is more likely to convince the reader that capital has decisively triumphed than that a world of post-scarcity is within reach.

Jaffe’s vision of post-work politics is more clearly rooted in her descriptions of how workers are organizing today, and she places more faith in the potential of their agency to remake the world. Utopia is present in her writing too, but it emerges concretely, when people act together in ways that challenge the structures of daily life. These moments of possibility can appear in unexpected places. Although they are often associated with autonomous movements like Occupy Wall Street that explicitly seek to disrupt the rhythms of everyday life, Jaffe points out that they also appear in more “organized” forms of action, like teachers’ strikes. We can even generate such moments when we imagine our lives otherwise: “What would you do with your time if you didn’t have to work?” she likes to ask. Such utopian moments won’t abolish capitalism, Jaffe acknowledges. But the projects that generate them give us a glimpse of alternatives and, most important, create the kinds of bonds among people that can drive struggles forward. Political power can only emerge, partially and unevenly, out of actual experiences and relationships—the kinds of relationships of solidarity and, yes, love, that organizing can create and sustain.

These divergent conclusions reflect a familiar division in left thought between stringent dissections of the structural compulsions of capitalism and attention to the generative power of human agency, epitomized in a previous generation by the clash between the French structuralist Louis Althusser and the English historian E.P. Thompson. In his adjudication of their debate, Perry Anderson concluded that Althusser’s abstract analysis was more helpful in appraising history, while Thompson’s account of workers’ consciousness was more useful in thinking politically. The tricky but necessary thing, of course, is to hold these perspectives simultaneously. From Benanav’s vantage point, it is easy enough to see where the movements and relationships Jaffe describes might fall short in building a different world. The harder and more important task before us is to figure out how they might succeed.

Alyssa Battistoniteaches at Barnard College and is the author of the forthcoming book Free Gifts: Capitalism and the Politics of Nature.