EDITOR’S NOTE: In the fall of 2021, a group of students at Wake Forest University took part in a class on data-driven advocacy. Their objective was to find a question that was broadly relevant to inequality, answer that question using basic tools of data science, and convincingly communicate that answer clearly to a broad audience in a partnership with the Puffin Nation Fund Writing Fellowships. This article is the second of the final products that came out of that course. The authors sought to understand whether racial disparities in crime and punishment have consequences that extend beyond the legal system, including employment, income, and mental health.

A legal system capable of delivering justice fairly and equally is a cornerstone of a functioning democracy. But in the United States, some racial groups are more likely to run afoul of that system than others. Approximately 1.3 million Americans are currently incarcerated, a higher per capita rate than any other country. And while one in every 17 white men in the United States will be jailed at some point in their life, one in three Black men will suffer the same fate. Black and Hispanic men are also sentenced to longer jail terms than their white counterparts. For these reasons, Black people comprise the majority of prisoners in the United States despite being a minority in the population at large. This racial disparity is reflected in data from the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth (NLSY), a survey following almost 9,000 young Americans throughout their lives starting in 1997. Survey respondents are chosen so that the sample matches the demographic characteristics of the US population. Figure 1 shows NLSY respondents and their incarceration status as of the start of the year 2017; Black people are considerably overrepresented among those who had spent time in jail.

Figure 1: Respondents to the 1997 National Longitudinal Survey of Youth by Race/Ethnicity and Incarceration Status

While racial disparities in crime and punishment are always concerning, they are especially troubling if their consequences extend beyond the legal system. Although a recent study using the NLSY showed no evidence that incarceration reduces wages, incarceration was associated with a lower likelihood of employment after release. That decreased employment in turn reduces the overall annual income of ex-convicts by $4,000–$5,000 per year, a 14–18 percent reduction in expected income compared to the non-incarcerated. If being imprisoned causes reduced income, then every sentence is in effect a life sentence in terms of its consequences for the convict—and any racial disparities become even more consequential. While a long-term study of prisoners before and after incarceration found no racial differences in the rate of wage growth prior to being incarcerated, wage growth after imprisonment for Black people was 21 percent slower than that of their white counterparts.

While racial disparities in crime and punishment are always concerning, they are especially troubling if their consequences extend beyond the legal system. Although a recent study using the NLSY showed no evidence that incarceration reduces wages, incarceration was associated with a lower likelihood of employment after release. That decreased employment in turn reduces the overall annual income of ex-convicts by $4,000–$5,000 per year, a 14–18 percent reduction in expected income compared to the non-incarcerated. If being imprisoned causes reduced income, then every sentence is in effect a life sentence in terms of its consequences for the convict—and any racial disparities become even more consequential. While a long-term study of prisoners before and after incarceration found no racial differences in the rate of wage growth prior to being incarcerated, wage growth after imprisonment for Black people was 21 percent slower than that of their white counterparts.

Why does this happen? Ex-cons do not seem to avoid the workplace because they think they will be shunned: Very few expect to be stigmatized, either in the form of being pushed away from their family or being turned away from a job. A study from 2010 found that “many of the [unemployed] ex-inmates in our sample did not experience trouble finding work upon their return to the community…rather they were not looking for work.” On the other hand, a different study discovered that the presence of incarceration on a résumé drastically reduces the possibility of a callback, with the reduction far worse for Black applicants (a 60 percent drop in the chance of a callback) than for white applicants (a 30 percent drop). In fact, a white person who has been incarcerated has a similar probability of a callback to a Black person that has not been in jail. And jail time negatively impacts an inmate’s mental health as well: The incarcerated are 21 percent more likely in the short term and 10 percent more likely in the long term to report depression than those who were never incarcerated. These ramifications of incarceration may hurt a person’s desire and ability to get and hold a job, or to advance in their career once they have one.

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →

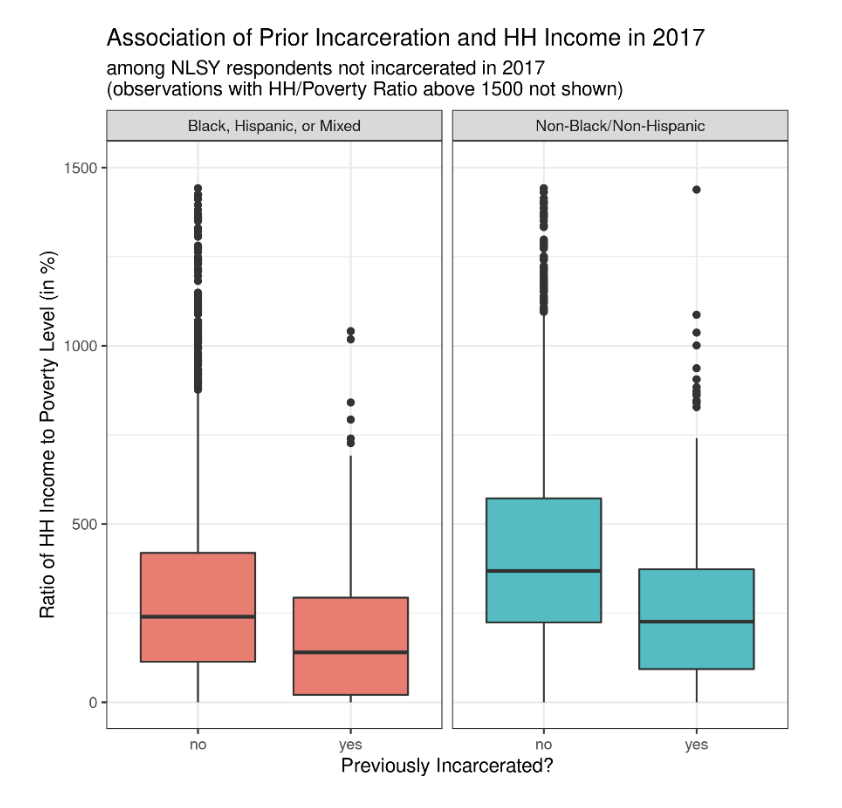

Previously incarcerated people are, on average, less prosperous than those who have never been in jail. Figure 2 compares the household income of ex-cons to those never imprisoned, using NLSY data for the year 2017. We separated the data into two race-ethnicity groupings: non-Black non-Hispanics (primarily whites and Asians) are in one group, and Black, Hispanics, and mixed-race respondents are in the other. In both groups, formerly incarcerated respondents have a lower income than those who were never incarcerated. But among non-Black non-Hispanic respondents, the previously incarcerated have incomes 200 percentage points lower (relative to the poverty line) than those who have never been incarcerated. That gap is double the size of the comparable difference between income among incarcerated and non-incarcerated Black, Hispanic, and mixed-race respondents. This may be because the non-Black non-Hispanic group has a much higher typical income and thus has further to fall if they are imprisoned. Indeed, formerly incarcerated non-Black non-Hispanics have an average household income that is close to the average among Black, Hispanic, or mixed-race respondents who have never been incarcerated.

Figure 2: Household Income and Previous Incarceration, by Race/Ethnicity

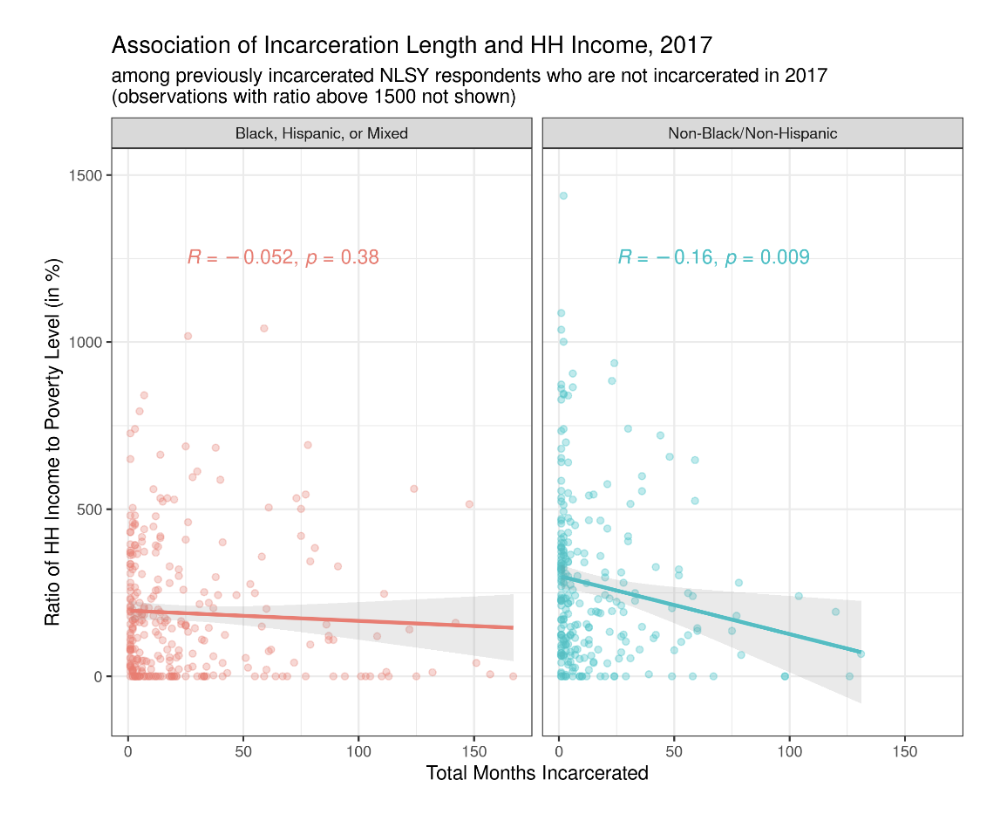

The racial asymmetry of incarceration’s consequences is also shown in Figure 3, which plots a respondent’s total months of incarceration against their household income in 2017. Among non-Black non-Hispanic respondents, every year in prison reduces a person’s income by about 2.21 percentage points relative to the poverty line. But length of incarceration has little impact on poverty for the group of Black, Hispanic, and mixed-race respondents. Regardless of the length of their stay in jail, the average income in this group is similar to the average of non-Black non-Hispanic respondents who have been incarcerated for six years. Any causal explanation for the effect of jail on post-release poverty must also be able to explain why minority groups experience nearly the same penalty on income regardless of the length of their sentence.

Figure 3: Household Income and Length of Incarceration, by Race/Ethnicity

Our analysis is not without shortcomings. The NLSY data set contains only 552 people who were imprisoned (and released) before 2017, a relatively small sample. The spike in incarcerations starting in the 1990s has created a large population of ex-convicts. Given the size of that population, we think that more data collection is warranted to help better understand the long-term consequences of jail time. Nor have we ruled out the possibility that reduced income in the past might encourage someone to enter a life of crime.

Our analysis is not without shortcomings. The NLSY data set contains only 552 people who were imprisoned (and released) before 2017, a relatively small sample. The spike in incarcerations starting in the 1990s has created a large population of ex-convicts. Given the size of that population, we think that more data collection is warranted to help better understand the long-term consequences of jail time. Nor have we ruled out the possibility that reduced income in the past might encourage someone to enter a life of crime.

Despite these reservations, it seems clear from our analysis that incarceration is an ordeal that lasts well beyond the length of the sentence. Even a short sentence has a dramatic impact on the income of someone from a minoritized racial group, much larger than that imposed on non-Black non-Hispanics. And given that effect on income, it is unsurprising that mass incarceration has been connected to racial wealth inequality in the United States. Fortunately, there is an alternative. Programs like drug rehabilitation, long-term house arrest, probation, and community service could allow offenders to continue pursuing an education, continue working, and continue constructing social networks rather than experiencing the tremendous loss of prosperity associated with time behind bars.