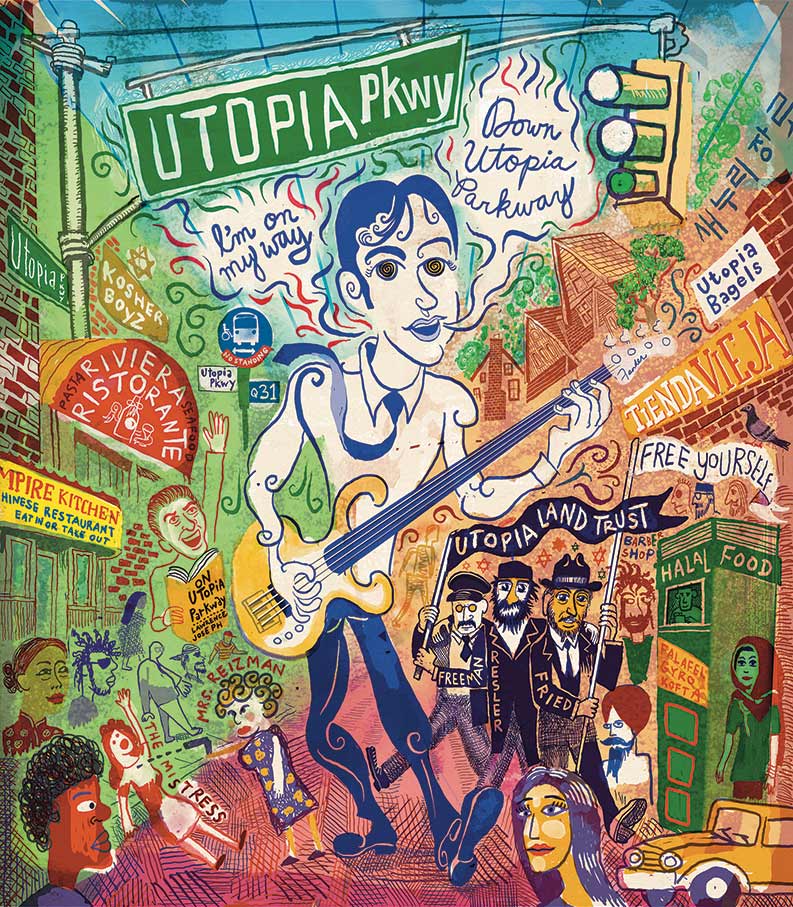

Illustration by Josh Gosfield.

Utopia Parkway. It’s a name that sounds like an oxymoron, so impossible, so perfect it shouldn’t exist. Yet it does, a 5.1-mile gash—four lanes of asphalt, sometimes two—running through New York City’s largest borough, Queens.

The roadway begins, if a line can be said to begin, in Beechhurst in the north, right at the water’s edge. From there it runs past the Long Island Expressway, down through Clearview, Flushing, and Hillcrest to Jamaica Estates in the south, where it fragments just before reaching the behemoth of Grand Central Parkway. This intersection is one of the most dangerous in the city, a place where bodies, bikes, and sometimes lives meet the harsh reality of the pavement. For much of this route, the road is banal, an endless procession of squat brick houses broken up by the occasional gas station or bagel shop. But as it approaches its southern end, it narrows and shifts, becoming something else entirely: a quaint, tree-lined street that deposits its travelers in a place that may or may not exist. The maps call it Utopia, but the residents call it Fresh Meadows, which is its own kind of irony.

Most New Yorkers probably haven’t been to Utopia Parkway, haven’t traveled its stingy curves, but they may have heard of it in passing, from local traffic reports or perhaps from a line of poetry or song. With a name like Utopia Parkway, the bards were bound to discover it, mining it for meaning. Lawrence Joseph turned it into a poem, as did Julio Marzán. Charles Mee turned it into a play. In the 1990s, the indie rock band Fountains of Wayne spun it into both an album and a song. When the lead singer croons, “I’m on my way / Down Utopia Parkway,” he means that he is on his way to somewhere bigger, somewhere exciting—somewhere else, anywhere else. It sounds almost like an anthem—or a dare. Or maybe it’s a promise, bound to be broken.

Utopia Parkway—both the idea and the place—is a deeply New York phenomenon: high and low, longing and stasis, bravado and banality, all pulling in the same direction. While it’s certainly possible it could exist somewhere else, it’s also unlikely.

To understand why, it’s necessary to go back in time to another moment of mass movement and flux, when utopian dreams seemed to be everywhere: in illicitly printed pamphlets, in the underground safe houses of banned Russian revolutionary movements, and carried on the waves by a new mass of immigrants heading to New York City.

It was the late 19th century. After the assassination of Czar Alexander II in 1881 and the wave of pogroms that followed, Jewish immigrants began to pour into the United States. By 1902, there were 585,000 in New York, making up over 17 percent of the city, most of them Eastern Europeans packed into the Lower East Side, where they sweated in the garment trades and began the now familiar story of economic ascent. But thousands of them had grander ambitions. Witness to political repression and racist mob violence, inspired by forbidden thinkers like Marx, Kropotkin, and the Russian radical Nikolay Chernyshevsky, these socialists and anarchists still nourished the dangerous dreams that sent them across the ocean.

In America, they found a degree of political freedom unthinkable in Russia, as well as a legal order that did not target Jews for specific persecution. Relatively free and socially unmoored, these radicals launched a dizzying range of experiments in collective living. They tried to stake their claims to utopia in a world they still thought of as new.

First, there was the Am Olam movement, in which hundreds of young idealists attempted to build agricultural communes in the spirit of the utopian socialist Charles Fourier. Their lack of farming experience didn’t matter—the earth itself would teach them, they thought—and so they bought acres of Arkansas forest and Louisiana swampland, sight unseen. Dozens died. Within a few years, most of the communes went bust.

One Am Olam member had better luck. The 22-year-old Abraham Cahan fled Odessa after members of his revolutionary sect shot the czar, but he ditched the back-to-the-land fantasies for the dance halls and firetraps of Orchard Street; in 1897, he founded The Forward, a socialist Yiddish newspaper whose circulation soon rivaled that of The New York Times. When my great-grandfather Sam Rothbort arrived in New York in 1904, The Forward was his bible. Sam himself tried to bridge the difference between New York reality and Am Olam’s bucolic delusions. At the height of his artistic success, he flounced out of New York and set up an egg farm on Long Island. A romantic vegetarian, Sam refused to kill male chicks. My great-grandmother spent her days feeding a quarrelsome and rapidly growing army of roosters, until the Depression hit and the farm inevitably collapsed.

Between 1890 and 1920, nearly 2,000 Jewish farmers bought land in the Catskills, sometimes renting out cottages on their property and combining fresh air with grand promises of vegetarianism, pacifism, trade unionism, and socialist, secular Yiddish. And in the mid-1920s, thousands of Jewish garment workers built housing cooperatives in the Bronx, each representing a different strand of leftist ideology. The Yiddish literature professor Marv Zuckerman grew up in the social-democratic Amalgamated Houses, built by the Amalgamated Garment Union in which his father was an official. The apartments were owned by the workers, who elected the management. Zuckerman remembers a close-knit, Jewish, working-class immigrant world of unions, mutual aid societies, May Day marches, and secular Yiddish night schools where portraits of Marx hung next to those of the great Yiddish writer Sholem Aleichem.

“I grew up thinking the whole cultural/intellectual world was socialist,” Zuckerman wrote. Residents came from “every point on the leftist political spectrum…. Anarchist, communism, Lovestone-ite-ism, Trotskyism, Zionism (both left and right), Bundism, Social democracy, socialism.”

Unsurprisingly, sectarian battles raged within the co-ops, among kids as well as adults. One friend of Zuckerman’s, the nuclear physicist Victor Gilinsky, arrived in the Bronx Amalgamated community with his Bundist parents in 1941, the end of a harrowing escape from Nazi-occupied Poland and Soviet Russia. One of their first visitors was Mrs. Stein, a communist neighbor who was collecting money for Birobidzhan, a Jewish autonomous oblast that Stalin had set up near the Russian-Chinese border. Gilinsky’s family had stopped in Birobidzhan as they made their way to Vladivostok on the Trans-Siberian Railway. A brief conversation in the station was all it took for his father to learn that the alleged Yiddish paradise was a police state where speaking Yiddish could land you in a prison camp. He told Mrs. Stein as much. “Fascist dog!” she hissed and stormed out. Victor, then 7, still remembers that Mrs. Stein’s son jumped him as he was leaving the building while she stood behind them screaming, “Hit him again!”

Utopia is serious business.

When Simon Freeman, Samuel Resler, and Joseph Fried formed the Utopia Land Trust in 1903, they likely had decidedly less ideological baggage. I know nothing more about these three men, whose real estate pursuits were their sole brush with history, but I imagine them as slangy allrightniks in bowler hats, trying to put their unpronounceable hometowns behind them. Who cared for Gozsephésa when they had Broadway? They meant to seize the Goldene Medine like a pot of gold.

The trio bought 50 acres between still rural Flushing and Jamaica, which they planned to divide into lots. In advertisements free of leftist rhetoric, they promised a Jewish “colony” that was leftist in practice. It would run on a cooperative basis, with industries and stores. They would name the streets Hester, Orchard, Delancey, to recall the Lower East Side motherland or maybe to underscore the contrast. For the next year, they flogged the project relentlessly in The Forward. “Free yourself!” commanded one ad placed in May 1905. “Free yourself from the high rent of New York! Free yourself from the cramped, filthy holes that the good-hearted landlord calls ‘rooms,’” from the firetraps that offered tenants two choices: jump out the windows or burn alive. “Come to our office,” the ad beckoned. “Our agent will pluck you from hell, where you cook and roast, and bring you to the Garden of Eden, our lots at the Utopia Land Company, where the air smells of perfume, the land is bedecked with nature’s green carpet, and the birds sing poetry in magnificent choruses. With a single word…you can have a peaceful, happy home, at a low price.” Where do I sign up?

They may have been apolitical, but Freeman, Resler, and Fried shared with Am Olam a grandiose rhetoric doomed to remain unfulfilled. In the summer of 1905, they promised The New York Times that within months, the first batch of “colonists” would arrive in their “Hebrew Utopia.” Funds ran out soon after, and the project collapsed. In 1909, the company sold its holdings to one Felix Isman of Philadelphia for $350,000.

From there, the neighborhood grew by dribs and drabs, as real estate speculators bought up farmland and cut it into lots for urban escapees to build their dream homes. In 1926, the Times first mentions Utopia Parkway as the boundary of the just-sold Whittaker Farm, and in 1929, the assemblage artist Joseph Cornell bought a wood-framed home at 37-08 from some Russian immigrants. He would remain there for the next four decades until his death.

Utopia Parkway makes its first appearance in The Forward in 1935, after Mrs. Reizman of 14-37 pulled a revolver from her kimono and shot her husband’s mistress. Her husband covered the corpse in kisses, neighbors said, and The Forward covered every salacious bit of the trial. This was a far cry from the respectable little burg Utopia’s founders envisioned. Still, for all the noisy shim sham of New York real estate, major development started only in the 1940s, when the Gross-Morton Park Corporation bought the land and plunked it full of Cape Cod–style suburban houses: 24 blocks of American nowhere. No trace remains of Freeman, Resler, or Fried, except for the parkway’s name.

In New York today, there is little room for the collective spirit that made the three men try to stake out their 50 square miles of Queens meadow. Like every proletariat, American Jews fought tooth and nail for their children not to follow in their footsteps. When they entered the middle class, those children no longer needed to pool their finances or their living spaces. The old Yiddish socialist New York still exists in fragments beneath the shiny, slightly shattered city. The Forward Building, Abraham Cahan’s Beaux-Arts headquarters, still stands, the Marx and Engels busts glowering from the front, but the interior was gutted and turned into luxury condos. The Bronx housing coops remain, but they are apartment buildings like any others.

At the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, I study Yiddish the way British schoolboys once studied Latin: to understand revered, but still alien, forebears. No matter how prosaic the subject, I cannot help but feel the electricity conveyed by the old German-Slavic words encased in holy letters; I feel like a medium, staring into a mirror to find ghosts.

Get unlimited access: $9.50 for six months.

In that spirit, I took the long subway ride over to Utopia.

Before the F train even reached Queensbridge, a man got on lugging a violin case. He was South Asian and wearing a sweat-stained red polo. He took out the violin and, with great verve, played the unmistakable bars of “Hava Nagilah,” the vaguely Zionist song that became a stand-in for all Jewish songs in the popular imagination. I gave him $2, notwithstanding the politics of the song’s origins.

I got off the train at 169th Street, with its row of stores offering elaborate henna designs and cash transfers to Bangladesh, then walked 38 minutes through the leafy streets until I reached Utopia Parkway. It was exactly the sort of unlovely beige with which this country likes to blot out its natural wonders, a sprawl of poky big box stores—TJ Maxx, Coldstone Creamery—that constitute the suburban wasteland of latter-day America. I ate an egg and cheese at a small Chinese deli that blared Britney Spears, “Hit Me Baby One More Time,” and stared through the window at Utopia Center, whose square architecture resembled a Midwestern gynecologist’s office. Was this the dream of Freeman, Resler, and Fried, I wondered: to be just as dull as everyone else?

I walked north from Union Turnpike, where the little brick houses sat on little lawns with picket fences. For-sale signs boasted names from everywhere—Stella Shalamova, Jiangwei (Wayne) Zhou. Posters from the Bukharian Chai Center offered an ice cream social and a reading of the Ten Commandments. Further up sat two-family brick homes, bounded by wrought-iron fences covered with globby paint. They could have been the fence I grew up behind in Far Rockaway. I kept walking until I hit Utopia Playground, a generous span of grass and asphalt that offered every childhood amenity: a basketball court and a soccer field, monkey bars and sprinklers, and plenty of concrete, where toddlers played and chattered in a babble of languages.

Almost half of Queens is foreign-born, and more languages are spoken in the borough’s 109 square miles than in any other place on earth. Though it was once the home of Archie Bunker and Donald Trump, the Queens of today has a cosmopolitanism that is working-class and solid—made by working people from everywhere who live together in this near-impossible city, in defiance of all the pundits who deny that people so profoundly different can carve a collective life together. If there is any utopia in Utopia, it is this. It is built by the Sikh, Black, and Mexican boys shooting hoops, by the Hasidic kids and Guatemalan kids battling over a soccer ball, by the tiny girl writing Chinese characters along the pavement while her brother hollers insults from his bike, by the mom in the sheitel who watches everyone’s children run through the fountain in this much-needed summer after the plague.

It’s imperfect, sure, and fraught and hard and filled with conflict, with hustlers and with bastards. The architecture sucks. It’s not how the books tell us a utopia should be. But utopia does not exist, by definition; Utopia, on the other hand, is as real as the baking asphalt beneath my feet.

I walk north and count the mix of names on the stores. Chen’s Cleaners. Bombay—an old movie theater where you can now eat samosas while watching Bollywood’s latest. The Utopia Jewish Center, where half the letters are missing in “Am Yisrael Chai.” I walk until my legs won’t walk, and then I keep on walking.

In his book Names of New York, Joshua Jelly-Schapiro writes about all the names for streets, bays, and alleyways whose origins have long since been forgotten. Where did Fresh Kills come from? How about Far Rockaway? Who were Ann and Catherine? The meanings died but the words remain, like the impressions of ancient sea creatures left on limestone.

I see Utopia Parkway like this. All the grandiose plans have faded into the prosaic present, the small houses inhabited by people from everywhere on earth, struggling each day to build for themselves and for their families a private sliver of a better world. Behind the chrome railings racked with roses, their kids grow up into New Yorkers. Like me, they will forget the old languages of their old countries but will grow up striving for their own utopia, their very own no place.

Molly CrabappleMolly Crabapple is an artist and writer for outlets including The New York Times, The New Yorker, Rolling Stone, and The New York Review of Books. She is the author of Drawing Blood and National Book Award–nominated Brothers of the Gun, with Marwan Hisham. Her work is in the permanent collection of the Museum of Modern Art.