Civic Resistance in Ukraine

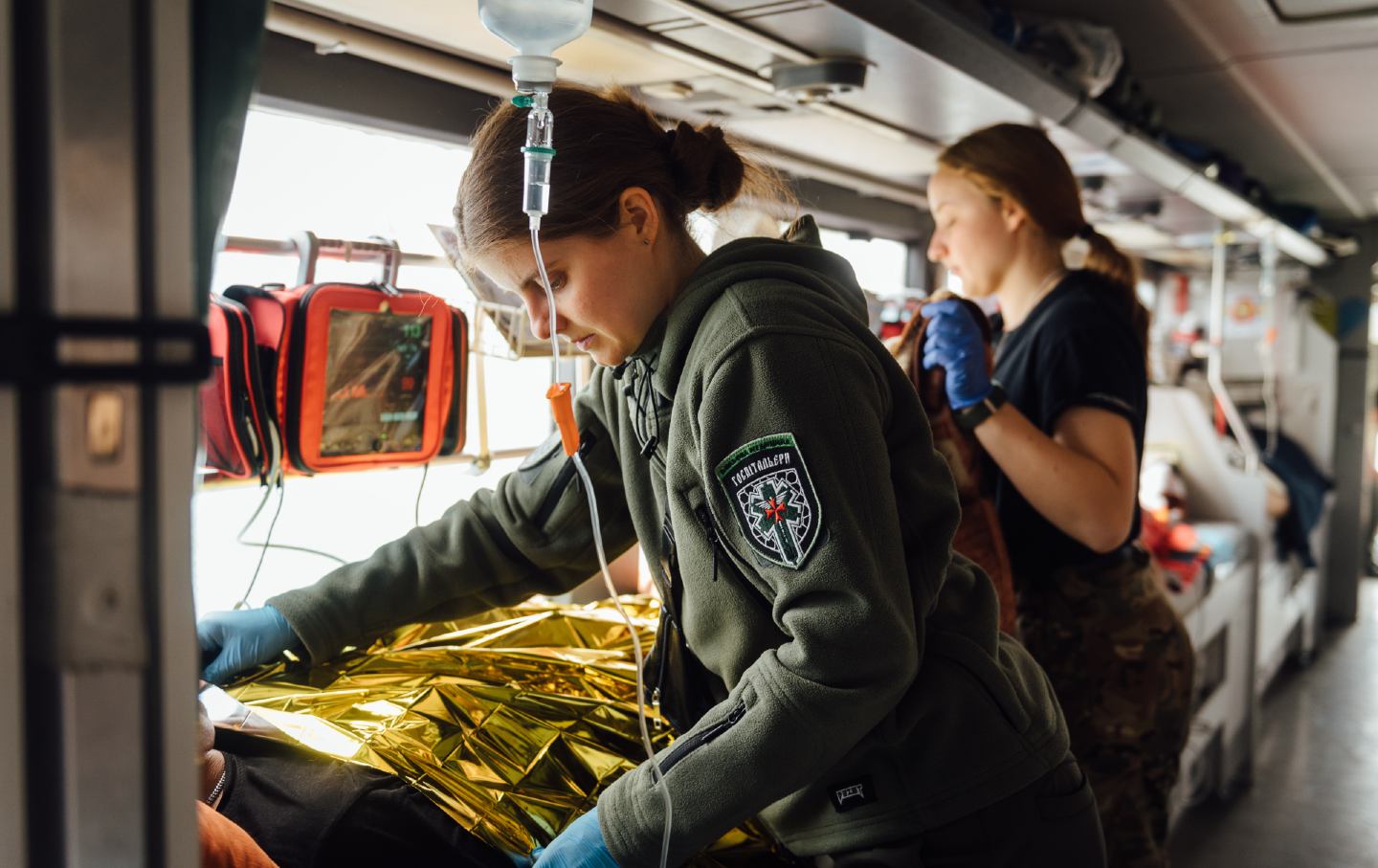

The grassroots upsurge is young, largely female, horizontally organized, tech-savvy, and mostly volunteer-run.

A broad swath of the West’s democrats is anxiously casting about to locate the source of—and antidote to—the free world’s democracy burnout. A virulent strain of authoritarianism is challenging Europe and North America, armed with Russian disinformation and exploiting concerns over immigration and other divisive social issues. Despite the occasional bright spot—like the victory of Poland’s centrists in October—there have been no epiphanies on how to redress the symptoms: low voter turnout, geriatric leadership, populist logic, and an uninspired political elite.

Perhaps for inspiration, we in the West should look beyond our own borders, to eastern-most Europe, where a newcomer to democracy is locked in a fierce struggle for survival. Let us look to Ukraine.

Under existential threat by Russia, Ukraine is battling furiously to preserve its republic, relying upon everything at its disposal, including a grassroots participatory swell that has galvanized the country. This democratic enthusiasm not only endures amid the worst conditions—our visits and hundreds of interviews do not confirm the picture of growing despair and defeatism portrayed in some media—but in many ways thrives more than ever. Our establishments could badly use a shot of Ukraine’s democracy mojo.

A National Resistance

This civic upsurge is what some protagonists call “national resistance,” from a 1957 guerilla warfare manual intended to ready the Swiss population for Soviet occupation at the height of the Cold War. Until now, it had mostly been left-wing revolutionaries in Asia, the Middle East, and Africa who called upon the idea that all citizen patriots, regardless of status or profession, should contribute to the country’s cause in any way possible: through covert actions, disobedience and noncooperation in occupied areas, seizing the initiative without orders from above. The entire population wages war against the aggressor, “to turn the lives of the occupiers into hell.”

The Ukrainians believe that people can do things: run off a corrupt president, drive accountability for war crimes, prevent the collapse of their capital city, assist in reconnaissance in occupied territories, care for their people, directly support their military—and hold their government to account. This has supplied them with a powerful commitment to personal agency, the antidote to the consumer democracy that has arisen in the cynical West.

The source of this determination is Russian leader Vladimir Putin’s brutal attempt to thwart Ukraine’s will for democracy, for the EU, and for NATO. Western cynics and pro-Moscow apologists deride or seek to delegitimize this choice, suggesting that some uncertain promise of the Bush administration to then–Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev 30 years ago proscribes the democratic legitimacy of Ukraine today. Putin’s ever-harsher dictatorship is the primary factor in Ukraine’s choice, not a few grants from Western philanthropists to Ukrainian democracy groups.

Legacy of Euromaidan

This spirit of resistance was born in the 2014 Maidan Revolution, also called the Revolution of Dignity. In 2013, Ukrainian demonstrators took to the streets to protest the decision by their pro-Russian president to block EU accession in favor of closer ties with Moscow. These demonstrations led to the toppling of the president, who fled to Russia, and marked the birth of modern Ukraine: a nation that defines itself by its Western and democratic orientation, even as the war has brought fraught issues of identity and language to the fore.

This flurry of popular engagement figures deeply in Ukraine’s social and political being. There has been, writes Ukrainian political scientist Yuliya Bidenko of the Zentrum für Osteuropa-und internationale Studien, a German research institute, “an overhaul of the system of relations between the civic sector, business, and state institutions. Some of these new relations resulted from reforms launched after Euromaidan in the areas of public services, education, decentralization, and digitalization; others were stimulated by the current war.”

Moscow’s response in early 2014 was the seizure of the Crimean Peninsula—and war. Since that time, civil society in Ukraine has steadily matured. Whereas past Ukrainian governments had worked against the interests of the people, in 2014 Ukrainians grabbed the reins of power.

Even if the oligarchical structures initially remained in place, and corruption blighted the economy, public ire fueled Maidan and, in its aftermath, civil society established itself as a force for accountability and transparency. This initiated a process that wrenched considerable power from once all-powerful oligarchs. A 2024 survey shows that over half of Ukrainians see civil society organizations as integral to the “control over the actions of the authorities, including ensuring the transparency of the distribution of funds.” And a May 2024 study shows that Ukrainian civil society “strongly perceives” that wartime resilience is linked to more effective institutions and the rule of law.

NGOs like Nashi Groshi (Our Money), Anti-Corruption Action Centre, and the Lviv Regulatory Hub stepped up to monitor public finance and press for democratic reform. Grassroots organizations like the 2022 Nobel Peace Prize–winner Oleksandra Matviichuk’s Center for Civil Liberties provided legal aid and support to demonstrators who suffered during the political upheaval and, with the full-scale invasion, would head up a monumental process to investigate war crimes.

All for One

The Russian attack is not just on the territory of Ukraine but on the Ukrainian people itself, its culture, identity, and political ethos. The barbarity in Bucha, Makariv, and Mariupol, among countless other towns where war crimes are being investigated, made clear that this would be the fate of those in occupied territories. Following the de-occupation in autumn 2022 of Izyum, a city in eastern Ukraine, investigators discovered a mass grave site in the pine woods off Shakespeare Road. In grave Number 319 lay the decimated remains of Vladimir Vakulenko, a writer of popular children’s books. If a beloved children’s writer is to be killed, it confirms to Ukrainians that any form of civil society faces death under Russian control. As argued by Matviichuk—who has personally undertaken hundreds of victim testimonials herself for a database of Russian atrocities—“Occupation is not peace, it is just another form of the war.”

Ukraine’s democratic rebirth in Maidan set the stage for the response to Russia’s full-scale invasion on February 22, 2022. Ukraine’s citizenry instantly poured out to bolster the war effort: Community groups manufactured Molotov cocktails; social media influencers raised money for weaponry; restaurants and bakeries cooked meals for troops; volunteers provided shelter and food for refugees; lawyers expedited Ukraine’s EU accession; civilians drove supplies to the fronts; first responders trained soldiers in emergency medicine; people showed up in droves to donate blood. The invasion spurred the volunteer organization Come Back Alive to procure over 600 armored vehicles, more than 6,000 thermal imaging cameras, and over 5,500 drones, according to the Europe Center of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →More than 60,000 women joined throngs of male counterparts volunteering for the armed forces. Facing such an existential crisis, the important distinctions in the West between army, organized civil society, and the citizenry fall away. This is a unified struggle for survival.

A recent study found that nearly 80 percent of Ukrainians donate money to the military and more than half volunteer in the civil resistance. As of April 2024, Come Back Alive has raised over 341 million dollars for the Ukrainian defense forces. The NGO PULSE has trained nearly 100,000 Ukrainians, a third of those in the security services, in first aid and frontline emergency medical skills.

“From the beginning, it stopped being a war between two armies, and turned into a war between the Russian army and the whole nation,” Maj. Gen. Dmytro Marchenko, a national hero for his defense of the key southern city of Mykolaiv, told IWPR. “Civilian doctors didn’t leave the city. They were treating wounded soldiers. Military vehicles were being filled up by local petrol stations. Ordinary people helped dig trenches to fortify the city. Everybody was part of a big machinery.”

“The army is fighting the war, but civil society is doing everything else,” says Natalia Klymova, deputy director of Ednannia, a Ukrainian NGO that provides financial support and training to over 500 civic organizations from across Ukraine.

A from-below campaign, for example, helped the Ukrainian army flesh out emergency medical services, which barely existed when Russia first invaded in 2014. In southern Ukraine, two Odesa men in their late teens, Fedir Serdiuk and Igor Korpusov, quit college to form a tactical medicine training program that has instructed over 28,000 soldiers and other security officers in emergency response techniques. They fund the program through a private sector business, crowdfunding, and foreign donations.

In western Ukraine, volunteers far from the front lines mobilized to collect aid and military supplies, embarking on grueling cross-country journeys twice weekly to deliver the goods in the east and south. A massive informal system of collection, storage, transportation, and supply mostly functions through communications on Facebook Messenger, often with greater efficiency in many cases than official army supply chains.

Others are already focused on rebuilding the physical wreckage caused by Russian attacks. Groups like RISE Ukraine; Reanimation Package of Reforms; and Resilience, Reconstruction, and Relief for Ukraine assemble hundreds of Ukrainian NGOs. Western donors see their participation as critical to a transparent and accountable process reconstruction.

The horizontal hierarchies serve the country well, including between military and civil society. In frontline territories, volunteers from groups like People in Need and Age Concern Ukraine work closely with army and police to support senior citizens and others who refuse to leave their homes in areas under Russian bombardment. People in Need estimates that it has helped 1.8 million people in Ukraine and Age Concern Ukraine now has 1,500 volunteers in nine regions of the country.

The demographic is young, largely female, mostly volunteer. In the Black Sea port city of Odesa recently, I entered one office after another full of twenty- to fortysomething women. Like many mothers, Tatiana Milimko, the 40-year-old chief editor of the Odesa-based news service USI.online, had sent her two children to Vienna with their grandmothers so she could stay to fight for the cause.

Democratic Values

Ukraine’s democracy is not perfect. Under the surface of wartime unity, Ukraine sanctions political rivalries and real debate about the government’s determined goal: Ukraine will settle for nothing less than a complete withdrawal of all Russian troops from all of its territories. Apparently, corruption is pervasive in the military conscription process (that’s why President Volodymyr Zelensky fired all heads the regional draft offices last year). There have been small demonstrations—in violation of martial law but not obstructed by police—to protest the undefined length of frontline tours. There is a consensus that elections are not possible amid full-scale war but will happen when the time comes. Meantime, the movement toward EU membership provides benchmarks for continuing democratic reform.

The share of Ukrainians who favor EU membership has soared since 2013: from 40 percent in that year to 95 percent today. The authoritarian, EU-skeptical parties thriving across western Europe—capitalizing on fear of migrants, yearning for a “strong leader,” and narrowly defined self-interest—wouldn’t stand a chance today in Ukraine. Ukrainians insist that the threat to Russia was not NATO on its doorstep but a functioning and flourishing democracy—this is what Putin is determined to destroy.

“Ordinary people can do extraordinary things,” says Nobel Peace laureate Matviichuk. “We are fighting with Russia for our values, and we have to defend our country, our people, and our democratic choice. There would be no sense for us to win the war with Russia and yet become like Russia itself.”

Sitting in her modest office in central Kyiv during the second anniversary of the war, she says there may be still more such dreaded anniversaries to come. “War is a poison on any society,” Matviichuk underlines. “The problematic of our situation is that we can’t postpone our democratization for the time the war will end, because we have no idea when it will happen. It means that we must balance between these two opposite trends, and to do and to succeed in two different tasks. First, to defend our country, our people, and our democratic choice, from Russian aggression. And second, to build democratic, sustainable institutions.”

We would go on to travel together in the coming weeks, as Matviichuk spoke out for Ukraine—and for further military aid—at a range of elite universities across the United States. Her tragic narratives of destroyed lives and tortured civilians were affecting, no matter how many times they were retold. But what most resonated with her receptive audiences was the realization that amid the horrors of this war, Ukraine reminds the West of higher goals than just our next purchases, that freedom and democracy really are worth fighting for. The most common closing question from the floor was always, “So what can we do?”

Both the European Union and the United States face vital choices over their commitment to open societies based on democratic values. All of us do. The time is now for disaffected voters and uninspired politicos in Europe and America to consider how much is at stake in the existential battles that are being fought. If Ukraine can mobilize its population behind a common purpose, then so can we. That’s what we can do.

Support independent journalism that exposes oligarchs and profiteers

Donald Trump’s cruel and chaotic second term is just getting started. In his first month back in office, Trump and his lackey Elon Musk (or is it the other way around?) have proven that nothing is safe from sacrifice at the altar of unchecked power and riches.

Only robust independent journalism can cut through the noise and offer clear-eyed reporting and analysis based on principle and conscience. That’s what The Nation has done for 160 years and that’s what we’re doing now.

Our independent journalism doesn’t allow injustice to go unnoticed or unchallenged—nor will we abandon hope for a better world. Our writers, editors, and fact-checkers are working relentlessly to keep you informed and empowered when so much of the media fails to do so out of credulity, fear, or fealty.

The Nation has seen unprecedented times before. We draw strength and guidance from our history of principled progressive journalism in times of crisis, and we are committed to continuing this legacy today.

We’re aiming to raise $25,000 during our Spring Fundraising Campaign to ensure that we have the resources to expose the oligarchs and profiteers attempting to loot our republic. Stand for bold independent journalism and donate to support The Nation today.

Onward,

Katrina vanden Heuvel

Editorial Director and Publisher, The Nation

More from The Nation

Why Palestinians Can’t Sleep Why Palestinians Can’t Sleep

Sleep deprivation is a form of torture. For Palestinians, it’s a regular way of life.

Life in Cuba Under Sanctions Life in Cuba Under Sanctions

Ordinary Cubans are trapped in a vicious circle of government mismanagement exacerbated by the US embargo.

Why Trump Is Threatened by South Africa Why Trump Is Threatened by South Africa

The country’s Constitution gives its citizens more than a right to the pursuit of happiness. But attempts to redeem that commitment to justice have enraged American reactionaries....

Rodrigo Duterte Used the Philippines’ US-Made Constitution Against Itself Rodrigo Duterte Used the Philippines’ US-Made Constitution Against Itself

The autocratic spectacle of Duterte’s presidency should be a warning to the United States.

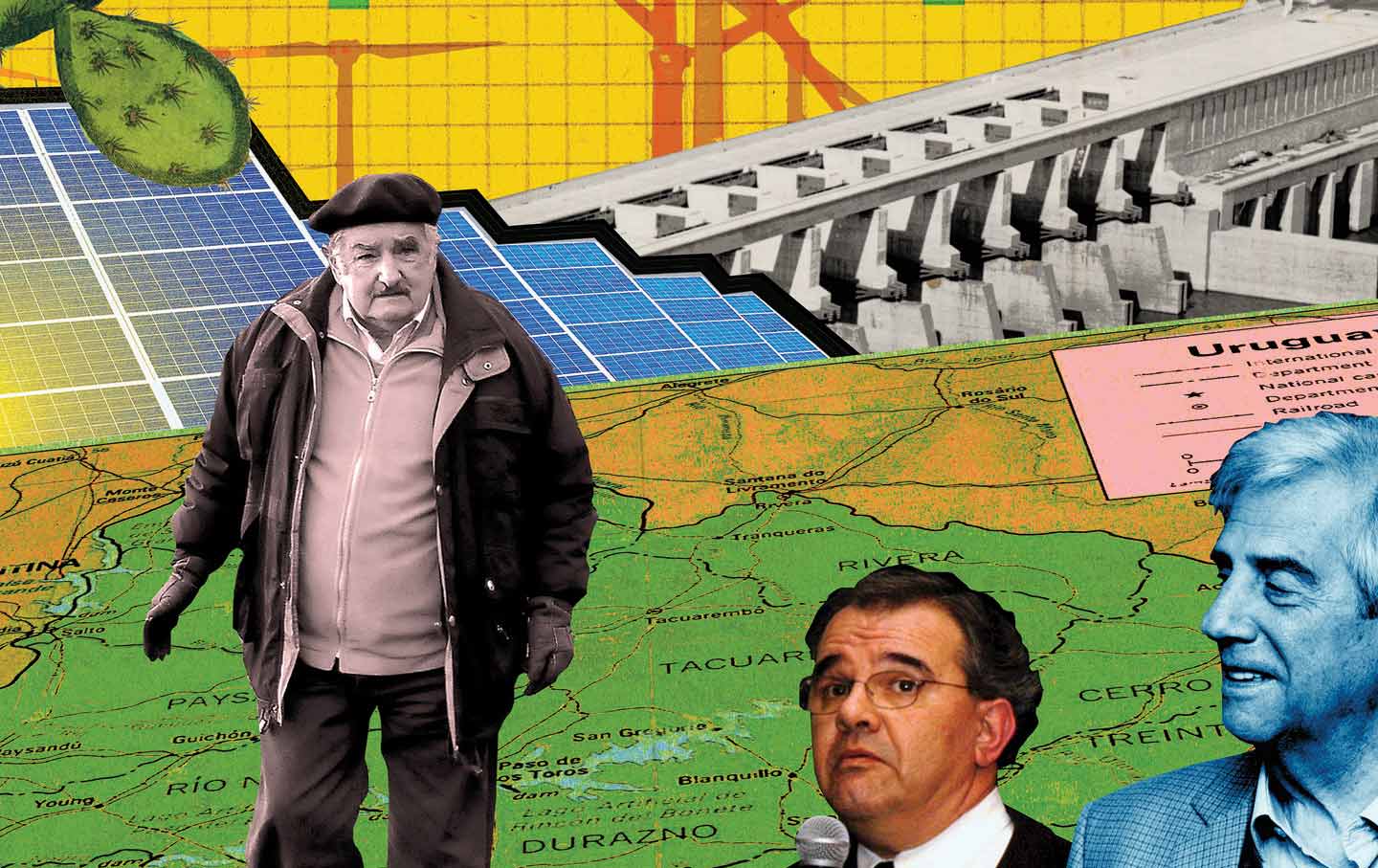

Going for Green: Uruguay’s Renewable Energy Revolution Going for Green: Uruguay’s Renewable Energy Revolution

With no fossil fuel reserves to rely on and domestic demand rising, the country had to get creative—or go broke just trying to keep the lights on. Here’s how they did it.

Andrée Blouin’s Revolutionary Lives Andrée Blouin’s Revolutionary Lives

The African political leader’s autobiography, My Country, Africa, also offers a larger story of empire, oppression, and resistance on the continent.