Meet the New Military-Industrial Complex

How the Pentagon–Silicon Valley alliance is harnessing AI to defeat China in World War III.

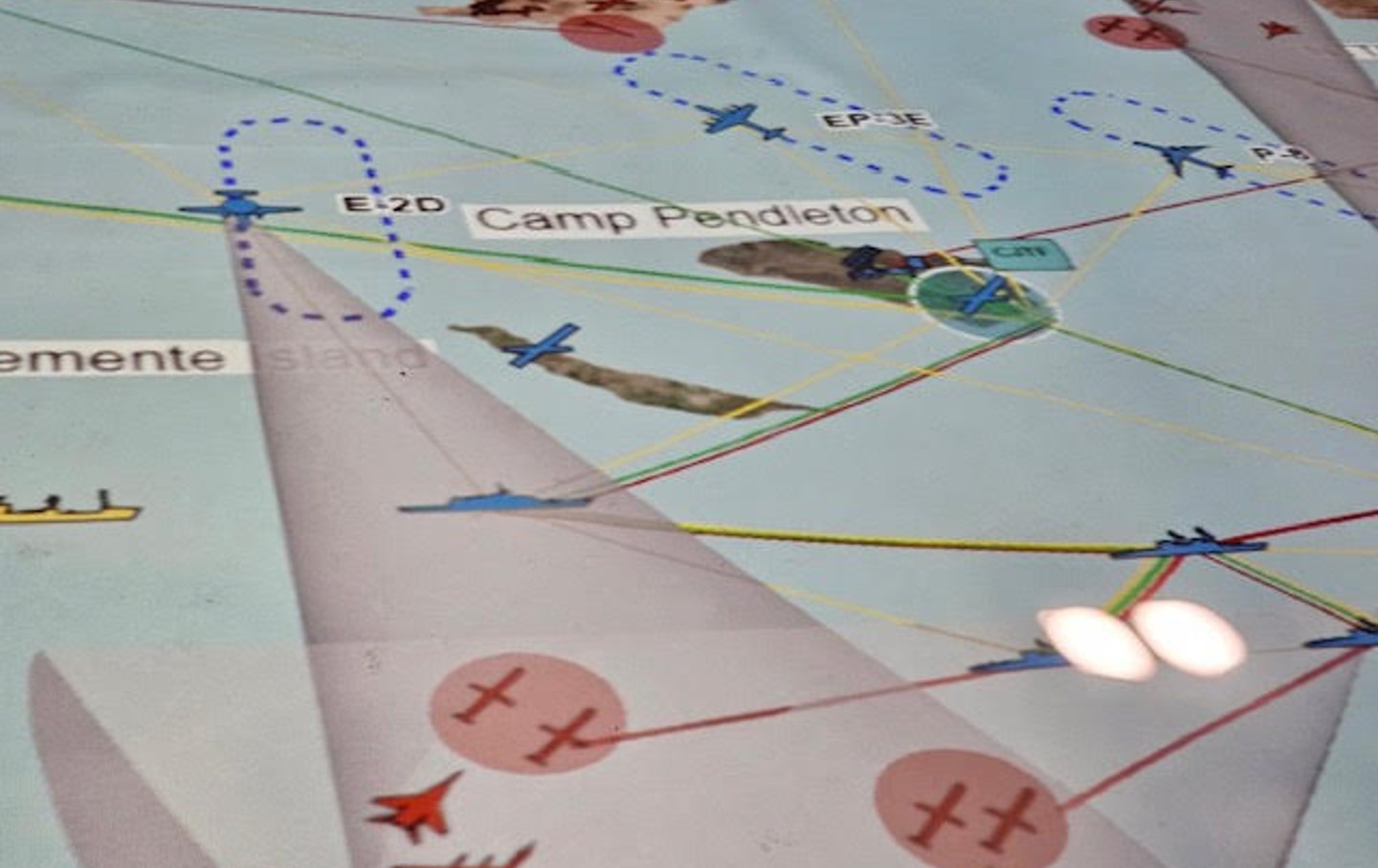

As I peered down inside a briefing tent at Camp Pendleton Marine Corps Base, California, on March 5, a giant floor screen projected the back-and-forth maneuvers of “red” (aggressor) and “blue” (defending) forces across the western Pacific. Over and over again, air and sea assets of the red force—identified as a “near-peer adversary” of the United States (a common stand-in for China)—penetrated deep into “blue” territory occupied by Washington’s allies, only to be repulsed or destroyed by blue’s own combat forces. In a scenario that can only be described as a modernized version of World War II in the Pacific, blue forces augmented their air and naval strikes with amphibious assaults to drive red invaders from islands they had seized at the onset of the exercise.

As I watched these computer-generated engagements, actual US and allied units—performing the roles of both red and blue forces—conducted air, sea, and ground maneuvers in an area stretching from Hawaii to Texas. To a considerable extent, these mock battles entailed the sort of encounters one would expect in any significant great-power contest, with ships, planes, and tanks firing rockets and missiles at each other. But this exercise, I learned, was distinct from most US training operations in that the principal aim of the exercise—known as Project Convergence Capstone 4, or PCC4—was not to test conventional firepower but rather the use of artificial intelligence (AI), automated data distribution, and other advanced technologies in weaving together disparate fighting units, whether US or allied, and ensure their success in battle.

“Future Joint [i.e., multiservice] and multinational warfighters [will] need integrated capabilities that operate at machine speed to win on the hyperactive battlefields of the future,” the Army indicated when announcing PCC4. “Capstone 4 is the pinnacle event for persistent experimentation in a campaign of learning to develop those essential capabilities.”

Project Convergence has been conducted every year or so by the Army’s Futures Command, a unit established in 2018 to design the weapons and tactics of next-generation forces. The first such event, Project Convergence 2020 (PC20), was held at Yuma Proving Ground, Arizona, and involved 500 Army personnel. Each subsequent iteration has grown in complexity, becoming a joint-service affair in 2021 (Project Convergence 2021, or PC21) and a multinational event in 2022 (PC22). (No exercise was held in 2023.)

This year’s version was the most elaborate and complex yet, with 4,000 participants drawn from all five US military services (Army, Navy, Air Force, Marine Corps, and Space Command) as well as the militaries of Australia, Canada, France, Japan, New Zealand, and the United Kingdom. PCC4 took place in two phases, stretching over a four-week period. Phase I, centered at Camp Pendleton, held from February 23 to March 3, was focused on a “maritime scenario in the Indo-Pacific,” and largely involved air and naval encounters. Phase II, conducted at the Army’s National Training Center at Ft. Irwin, California, was held from March 11 to 20 and emphasized land combat maneuvers, including the extensive use of unmanned weapons systems. Much of this was off-limits to the public, but I was one of about 20 members of the press invited to Camp Pendleton on March 5 for a series of briefings and weapons demonstrations.

“This year, we have increased the threat envelope to ten times what we did [in PC22],” Lt. Gen. Ross Coffman, deputy commander of the Army Futures Command told our media contingent on March 5, following Phase I. Noting that two multi-domain task forces were brought in to assist with communications and data-sharing, he claimed that “we’re able to effectively move data for the first time in an Indo-Pacific scenario at a magnitude never seen before.”

Speaking at Camp Pendleton’s Pacific Views Event Center, Coffman went on to explain that a data-sharing network established by PCC4 served as an electronic “bridge,” allowing the instantaneous sharing of combat information between every element of the joint force. “This bridge absolutely allowed us to pass information from multiple sensors to multiple shooters so that an Army sensor passed data to a shooter in every service and every service sensor passed the same to every other service,” he declared.

Being able to share information quickly between disparate combat units spread across the wide expanse of the Pacific was said to be essential to ensure a US or allied victory in any future conflict with China (or, as it was put, a “near-peer adversary”). Because our presumed enemy has such a vast inventory of ships, planes, and missiles, I was told, the US-led coalition must be able to pinpoint those forces quickly and disable them before they can inflict serious damage, using whichever “shooters” were best positioned to do so. A failure to act quickly, it was argued, could result in substantial US or allied losses and a long war of attrition with no sure winner.

CJADC2 and “Replicator”

The PCC4 network was used not only to transmit targeting data and attack orders during Phase I of Project Convergence but also as a model for the Pentagon’s Combined Joint All-Domain Command and Control (CJADC2) system—an elaborate network of sensors, data links, and automated battle-management systems linking all US military units. “CJADC2 is a war-fighting necessity to keep pace with the volume and complexity of data in modern warfare and to defeat adversaries decisively,” explained Pentagon spokesperson Eric Pahon on March 5. “CJADC2 enables the Joint Force to ‘sense,’ ‘make sense,’ and ‘act’ on information across the battlespace quickly using automation, artificial intelligence, predictive analytics, and machine learning to deliver informed solutions via a resilient and robust network environment.”

Until now, relatively little detailed information about CJADC2—its costs, components, and contractors—has been made available to the public. In a rare public discussion of the project, Deputy Secretary of Defense Kathleen Hicks told representatives of US defense contractors last August, “It’s a whole set of concepts, technologies, policies, and talent that’s advancing a core U.S. warfighting function: command and control.” With CJADC2, she continued, “we’re integrating sensors and fusing data across every domain, while leveraging cutting-edge decision support tools to enable high-tempo operations.”

The importance accorded CJADC2 by top Pentagon officials was underscored by Hick’s visit to Camp Pendleton on March 4 to observe Project Convergence and its test of CJADC2 technologies. According to a Pentagon “readout” on her visit, Hicks conferred with senior officers about the status of efforts to integrate the historically incompatible communications networks of the respective armed services into a shared, multiservice web—a mammoth task said to be posing numerous “challenges.”

While at Camp Pendleton, Hicks also sought to learn more about the military’s progress in integrating autonomous weapons systems—combat devices largely guided by AI, rather than human operators—into its combat lineup. The development and deployment of such systems is essential, she declared in her August 2023 address to members of the National Defense Industrial Association, if US forces are to prevail in any future conflict with China’s military, the People’s Liberation Army (PLA). Given the PLA’s advantage in conventional measures of power (“more ships, more missiles, more people,” as she put it), the US military must flood the future battlespace with multitudes of “all-domain attritable autonomous” weapons—low-cost, disposable, and self-piloted drones of all sorts. “We’ll counter the PLA’s mass with mass of our own, but ours will be harder to plan for, harder to hit, harder to beat,” she asserted.

As Hicks acknowledged, however, the existing Pentagon procurement system is not currently organized for the acquisition of many high-tech devices of this sort, having long focused on the purchase of “big-ticket” items—ships, planes, and tanks—from the leading arms manufacturers. These companies—the primary bulwark of the existing military-industrial complex—are good at what they do, Hicks noted, but do not possess the technical and entrepreneurial skills to produce large numbers of AI-governed “attritable autonomous” weapons quickly. Rather, the Pentagon will have to rely more on start-up firms—many with roots in Silicon Valley—to provide the necessary capabilities. Gaining access to those capabilities, she affirmed, is the principal goal of Replicator. “America still benefits from platforms that are large, exquisite, expensive, and few,” she declared last August. “But Replicator will galvanize progress in the too-slow shift of U.S. military innovation to leverage platforms that are small, smart, cheap, and many.”

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →Although a fresh initiative, Replicator enjoys strong support from Congress, a last-minute allotment of $200 million in the fiscal 2024 defense appropriation bill and promises of an additional $500 million in the 2025 budget. But with many more millions—eventually billions—of dollars likely to follow as the program gains momentum, many defense-oriented high-tech start-ups like Anduril, Palantir, and ShieldAI have begun lending their products for military exercises like Project Convergence, hoping this will lead to long-term procurement contracts.

During Phase II of PCC4, for example, a number of Anduril Ghost-X surveillance drones were used by infantry forces on the blue team to spy on red team fortifications and mark their locations for follow-up ground attack. A sleek, insect-like device with a three-foot rotor, the Ghost-X has a range of 25 kilometers and can carry a variety of sensor systems. Also on display at PCC4 was the Hive unmanned aerial system (UAS), a drone specifically designed to be flown in autonomous swarms—drone packs able to coordinate their moves and inundate enemy defenses with assorted munitions. The Hive drones tested at Fort Irwin, I was told by an Army official overseeing its use, are “prototypes for an offensive small, unmanned aircraft systems swarm in a group of three or more UAS platforms to perform tasks cooperatively, in a decentralized manner, after receiving very limited control from a human operator.”

According to General Coffman, this year’s Project Convergence witnessed a “tenfold” increase in the use of unmanned weapons systems as compared to the previous version, suggesting that this trend will continue in the future. But, like Deputy Secretary Hicks, Coffman and other senior officers at PCC4 indicated that the necessary technology is not available from the Pentagon’s own munitions labs or from its traditional defense contractors like Boeing and Lockheed Martin but must be derived from start-ups like Anduril and Palantir that possess the required expertise. “Industry, in a lot of ways, commercial technology, is leading—especially in data networks [and] unmanned systems,” said Army Chief of Staff Gen. Randy A. George during a March 5 briefing at Camp Pendleton.

With the Department of Defense poised to spend billions of dollars on a wide assortment of unmanned systems—and tech start-ups expected to reap new fortunes in the process—one can see the emergence of a new military-industrial complex, largely centered around Silicon Valley. Not surprisingly, then, retired military officers are flocking to Silicon Valley in search of lucrative positions while private equity firms are pouring money into the new concerns.

According to a recent survey by The New York Times, at least 50 former Pentagon and national security officials—most of whom left their posts within the past five years—are now working in defense-related venture capital or private equity firms. Among them is Mark T. Esper, a secretary of defense during the Trump administration who now represents Red Cell, a venture capital firm that has invested in military start-ups like Epirus, a maker of anti-drone technology. Another such figure is Ryan McCarthy, a former secretary of the army who helped launch the Futures Command and now represents a venture capital firm with defense-related investments.

Where Are We Headed?

Project Convergence Capstone 4 can be viewed as a perfect microcosm of America’s current political-military-technological configuration and its evolving nature. I drew many insights from the three-week-long exercise, but three stand out.

First, the US military is totally fixated on preparing for a war with China. This is evident both in the Pentagon’s formal doctrine and in the words and actions of senior military officers. The scenario governing PCC4, for example, was clearly based on a hypothetical Chinese assault on a US-friendly island state in the western Pacific—Taiwan? The Philippines?—and an ensuing region-wide conflict that brings in Australia, Japan, New Zealand, and the UK as well as the US. With this in mind, the primary aim of the exercise was to test the communications and battle-action links connecting those forces. “We know that when we go to fight anywhere in the world we’re going to be fighting with our joint partners,” said General George at the March 5 briefing, “and we’ll need to rely on any sensor, any shooter, and tie them together.”

My interlocutors at Camp Pendleton—whether uniformed military officers or civilian contractor representatives—seemed to have scant concerns about the possible consequences of this single-minded focus on gearing for a war with China. “We hope to avoid war,” General Coffman affirmed, “but if called upon, the men and women of this country will fight side-by-side with our allies and partners.” Take this sentence—which assumes participation by Australia, New Zealand, and the other countries represented at PCC4 in any future war with China—and combine it with the region-wide scale of the (mock) operations at PCC4, and one might understandably conclude that we are looking at a World War II–like scenario fought with modern weapons. Given the immense destruction this would cause on all sides, what assurances do we have that the two belligerents will foreswear using nuclear weapons to stave off defeat? Certainly, no such assurances were provided at Project Convergence.

Secondly, and closely related to the first, is the observation that US officials are absolutely determined to exploit AI and other advanced technologies to defeat China in any future conflict. This is the overriding objective of the Replicator initiative and was the basic organizing principle of the PCC4 battle scenario. Again and again, I was told that the US military must employ advanced technologies to attain “information dominance” in any future US-China war, enabling US and allied forces to detect and strike Chinese threats before they can inflict significant damage on coalition assets.

But, here again, I heard very little about the dangers of overreliance on artificial intelligence and related technologies. While the sophisticated algorithms used to create ChatGPT and other “generative AI” programs like it can achieve remarkable results, they are also known to produce false and misleading outcomes, called “hallucinations” by industry insiders. Relying on these and other advanced AI programs to govern military systems—especially those involved in the command and control of combat forces—thus poses a significant risk of systemic failure, possibly putting soldiers’ lives in danger or provoking an unintended escalatory incident. Deputy Secretary Hicks and other top officials have sought to reassure skeptics on this matter, claiming that humans will always remain “in the loop” when it comes to critical combat decisions. What I experienced at Pendleton, however, was a drive to accelerate the military utilization of AI and autonomy at any cost, suggesting that humans’ control over such systems is diminishing rapidly.

Finally, as suggested earlier, we are witnessing the emergence of a new military-industrial complex based on a Pentagon-Silicon Valley alliance. What this shift portends for US domestic and foreign policy remains to be seen, but, at the very least, it will result in increased pressure on Congress to raise military spending and an even greater emphasis on preparation for a war with China. Like the traditional arms manufacturers, the new tech entrepreneurs have hired a bevy of lobbyists to push their cause in Congress, while many have spoken publicly about the need to counter Beijing—adding further fuel to the already rampant war hysteria in Washington.

Some of my observations can be found in the US media, but not all three of them connected like this, and not without a full assessment of the dangers they pose. As should be clear, however, these trends entail significant risks to US and international stability, and so demand our close attention—and, where appropriate, demands for significant regulatory action. In particular, we should be expressing far more concern about the hurried application of AI and autonomy to warfare and insist that humans must, in all circumstances, remain in full control of all war-making systems; autonomous weapons that cannot be assured of such control should be banned altogether, as advocated by Austria, France, Germany, and many other countries.

Hold the powerful to account by supporting The Nation

The chaos and cruelty of the Trump administration reaches new lows each week.

Trump’s catastrophic “Liberation Day” has wreaked havoc on the world economy and set up yet another constitutional crisis at home. Plainclothes officers continue to abduct university students off the streets. So-called “enemy aliens” are flown abroad to a mega prison against the orders of the courts. And Signalgate promises to be the first of many incompetence scandals that expose the brutal violence at the core of the American empire.

At a time when elite universities, powerful law firms, and influential media outlets are capitulating to Trump’s intimidation, The Nation is more determined than ever before to hold the powerful to account.

In just the last month, we’ve published reporting on how Trump outsources his mass deportation agenda to other countries, exposed the administration’s appeal to obscure laws to carry out its repressive agenda, and amplified the voices of brave student activists targeted by universities.

We also continue to tell the stories of those who fight back against Trump and Musk, whether on the streets in growing protest movements, in town halls across the country, or in critical state elections—like Wisconsin’s recent state Supreme Court race—that provide a model for resisting Trumpism and prove that Musk can’t buy our democracy.

This is the journalism that matters in 2025. But we can’t do this without you. As a reader-supported publication, we rely on the support of generous donors. Please, help make our essential independent journalism possible with a donation today.

In solidarity,

The Editors

The Nation